Title

Between woman and camera – on role models produced through photography

https://www.doi.org/ASPWAW.29564158.MCE.2022.8.7

http://miejsce.asp.waw.pl/en/between-woman-and-camera-on-role-models-produced-through-photography/

Abstract

The essay focuses on analyzing the various discourses that have driven the expansion of the photographic industry and technology both historically and today. Photography is understood here as a socially functioning medium that is subject to commercial strategies. Walentynowicz refers to her artistic research practice on how different technological and commercial discourses affect gender relations and role models in society. In the first part of

her essay, she presents historical discourses aimed at constructing a relationship between woman and camera - first as a modern tool of liberation, then as a necessary household utensil of a resourceful housewife. She also discusses gender-specific discourses in photography in socialist Poland, which, despite having its own photochemical industry, remained on the fringes of the global photo market. She concludes her analysis with a reflection on the current spread of digital photographic images and the ability they offer female-identifying persons to bridge the domestic and public spheres.

DOI

Introduction

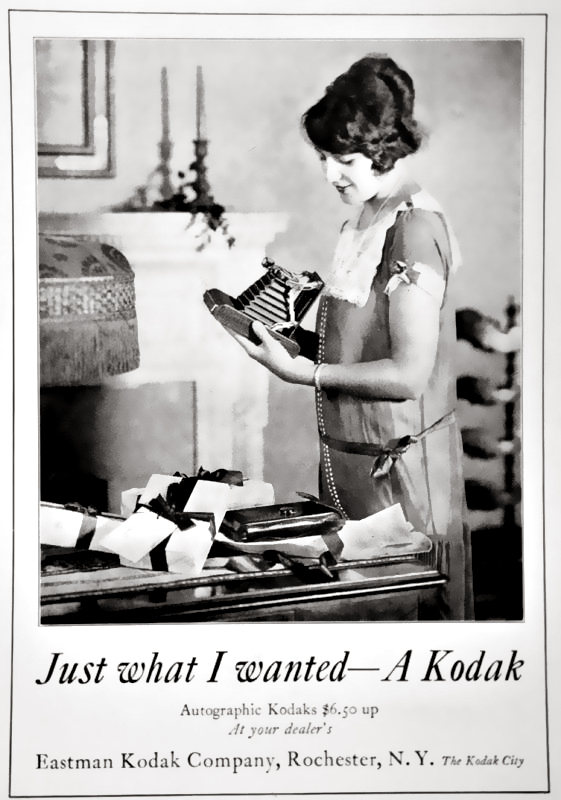

The article focuses on the construction and deconstruction of gendered roles within the medium of photography through both commercial and socio-political discourses. The cultural context of early inventions and advertisements of Eastman Kodak Company remains a reference point for reflecting on positioning of women towards photographic technology in other cultural contexts, especially that of Central and Eastern Europe. The impact of the development of photographic technology on women’s social roles 1 is a primary research issue. The article brings together various sources from different periods – stories of specific places and figures – that make up a fragmented map of social history of photography.

Beyond the visual aspect of photography and its categories of representation, I look at photography primarily from a sociological perspective that not only asks what kind of pictures people make, but also how pictures influence their lives. I examine women photographers’ association with the domestic sphere as a product of politics, economics and technology. In this essay I would like to trace these processes and ask how they have shaped the historical and changing positions of women in photography and how they in turn have constructed role models that go beyond the field of photography. The essay argues that through photography women have often found a way to subvert gender roles and cross the boundary between the domestic and public spheres.

The modern girl

The development of photographic technology coincided with the period when Europe and North America were heavily affected by internationalization – the flow of goods accelerated, and capital moved relatively freely between countries. Industrialization enabled standardized production of household goods using economies of scale, while rapid population growth created sustained demand for goods. Many countries started adopting liberal trade policies after years of protectionism. With the movement of global mergers, markets expanded and prices fell. This is how the culture of mass production and mass consumption developed, of which photography was also part.

At first a fad for the members of the upper class, after few decades photography transformed from a complex, alchemy-like activity to a popular social practice. The turning point was 1888, when the Kodak company of Rochester in the United States started selling film in rolls and designed a compact camera for such a film as a simple box in which it was enough to ‘press a button’, and which could be taken on the go easy. Moreover, Kodak separated the darkroom processing from the shooting process. Within five years after its introduction, the company expanded interest in amateur photography to about a third of the US population – by the end of 1905, it had sold over 1.2 million cameras. An important aspect was the low price of the camera: the Brownie was a simple cardboard camera that costed only a dollar. On vacations, weddings, birthdays or simply at home, cameras became ubiquitous 2 and more often than we might think, women were the ones holding them.

The icon of the new style of photography was the Kodak Girl, who first appeared in the company’s commercials in 1892. She was a young woman whose pretty face and stylish costumes, as Nancy West puts it, ‘contextualized photography within the contemporary discourses of fashion and female beauty, while her youthful appearance suggested the ease, pleasure and freedom of taking pictures.’ 3 These early ads featured independent women photographing the world: in the winter and the summer, skiing or playing tennis, in a car or on a boat – the Kodak Girl carried a camera with her everywhere. Alone and adventurous, the Kodak Girl was the ‘epitome of modern, confident womanhood’ 4 , who promoted snapshots as enhancement of vacations, leisure and mobility, and allowed the company to capitalize on the association between independent women and the freedom of the camera.

As Małgorzata Radkiewicz points out, together with promoting its technological achievements and making snapshot photography easy and simple, Kodak sanctioned a certain poetic of vitality, youth, and active lifestyle. Moreover, images of tourist women in different means of transport, always equipped with a functional Kodak camera, created associations with a modern, independent, and mobile way of living that many viewers would love to follow. 5 Radkiewicz investigated several photographic albums of women in the Cracow area between 1910-1930 to find that the Kodakery lifestyle infiltrated the Polish middle class as well 6 Here too women wanted to imitate the lifestyle of The Kodak Girl. Looking closely at the album of Kosinski family, Radkiewicz points out that ‘the active and ‘open-air’ aspect of the Kosinki sisters’ photographs seems to be an almost literal repetition of Eastman Kodak’s advertising campaigns, whose commercial offer reached the Polish Galicia. 7

Women remained a special segment of the Kodak market for decades. Each year, Kodak published dozens of books and brochures that provided practical advice for amateurs and photography enthusiasts whose main group of their readers were women. Almost every issue of the brochures published from 1913 to the early 1930s had a female photographer on the cover – alone, in the company of other women or with children. Especially for women, Kodak produced cameras from the Kodak Vanity line, available in various colours (red, blue, green) that fit the camera into the line of fashion accessories.

Mothers and housewives

At the time when photography was ‘born’, and in principle from the 18th century on, a patriarchal ideology of separate spheres was governing the social relations, based primarily on the notion of biologically determined gender roles and patriarchal religious doctrine. This ideology held that women should avoid the public sphere – the domains of politics, gainful employment, commerce, and law. The public sphere (German: Öffentlichkeit) is an area of social life in which individuals can meet to freely discuss and identify social problems, and through this discussion influence political activities. 8 The home sphere, in turn, can be defined as a series of interrelated ideas that characterize the family home as a special domain of a woman – woman idealized as an angel in the house, the guarantor of the spiritual and moral welfare of the family.

Around 1910, Kodak commercials started to focus on the importance of photography in creating a home atmosphere and preserving family memories. Nancy West argues that the real turning point was World War I when Americans, fighting at the front, needed photographs to confirm the unity of the family. As soldiers returned from the front lines, the women returned to taking care of the housework and raising children. Kodak took advantage of the strengthening discourse about the family and again relied on women for new advertising campaign. Photographing, which used to be spontaneous fun, has now turned into the obligatory act of preserving family and childhood on film, and the young liberated Kodak Girl was now a woman placed safe at home. However, this pivot was again dictated by technical issues: Kodak was constantly improving its films so that they could be exposed not only in the strong outdoor sun but also indoors. Around 1915, amateurs of photography were able to take high-quality photos at home. Once again, a wealth of literature encouraged taking pictures indoors, including the regularly published booklet At Home with the Kodak and advertisements that praised home as a ‘bountiful source of charming activities waiting for the sharpshooter’.

The women in Kodak commercials have since been portrayed as resourceful housewives who use photography to preserve family stories. They were encouraged to be archivists, that is, meticulous chroniclers of family life: if a woman wanted to be seen as a caring mother and responsible housewife, she had to document her family’s development. Preserving the family history has become a moral imperative for women, prompting them to seek pleasure in producing and consuming images as an activity that holds the family together. The careful design of the photo album was an integral, if not a necessary, part of family interactions and a key aspect in inspiring the increasing use of the camera in everyday family life. 9

In her recent exhibition at the Zacheta Gallery in Warsaw, American artist Susan Mogul recalled the engagement of her mother with photography: ‘Kodak promoted the notion that if women wanted to be responsible mothers and wives, they would be the memory keepers of the family. They would ensure that all key moments of the family life were duly captured.’ 10 Housewives persisted in Kodak’s advertising campaigns for decades – in the 1940s and 1950s, Kodak ads appeared in women’s lifestyle magazines such as Life, Look, Colliers and Ladies Home Journal. In advertisements from the 1960s, celebrities or celebrity wives advertised the benefits of keeping a family archive on Kodak film. In this way – through technology – Kodak’s adverting campaigns constructed different roles for women. Influenced by the international success of Kodak, many producers targeted their advertising campaigns at women, now key figures in the field of emerging consumerism. Finally, women became the largest segment of the US photography market: by the 1970s, over 60% of the photos in the US – the world’s largest photography market – were taken by women. 11

The research into Kodak advertisement thus shows that this association of women photographers with the domestic sphere has been a product of politics, economy, and technology.

On the margin of the global market

In context of the Central and Eastern European region, the photochemical industry in the pre-war Poland functioned quite well: in Warsaw Piotr Lebiedziński started the production of photosensitive materials as early as 1888. And from 1936 the owners of the Factory of Paper Upholstery and Colored Papers ‘J. Franaszek S.A.’ started a branch dealing with production of photographic papers and negative films. In 1926 at Garbary street in Bydgoszcz, the factory ‘Alfa’ started its production of photographic plates, films, and papers. Its founder was the industrialist Marian Dziatkiewicz. Apart from the native materials, photographic materials from foreign producers such as German Agfa and American Kodak were also available in Poland. In pre-war Warsaw, there were at least two ‘Kodak’ brand stores. 12

After the Second World War, most private enterprises in Poland had been nationalized. As Barbara Klich-Kluczewska mentions in her study on the photographic market in post-war Poland, although many merchants did much to establish or renew commercial contacts broken during the war, since 1947 policymakers aimed to shut down or nationalize all private commercial companies. This campaign went down in history as ‘the battle of trade’, and was the way for the authorities ‘not only to deal with private and cooperative trade but also to implement the concept of the inferior status of the entire trade in a socialist economy’. 13 In consequence, the destruction of private merchants resulting from ‘the battle of trade’, concluded in a dramatic decline in the workforce and its competencies.

In 1945, a state-owned enterprise ‘Film Polski’ was established in Poland (renamed ‘Central Office of Cinematography’ in 1951), which had the exclusive right to conduct photochemical production in Poland. After a decision of the director of Film Polski, the former Warsaw factory ‘J. Franaszek S.A.’ was rebuilt as the Photochemical Plant No.1, and the former ‘Alfa’ in Bydgoszcz changed to the Photochemical Plant No.2. 14

At the beginning of 1953 the Central Authority for Trade in Photographic and Precision and Optical Materials was established. It was in charge of the entire distribution of photographic materials to individual customers. Its subsidiaries were warehouses and the ‘Foto-Optyka’ Trade and Service Enterprise. The non-market customers, i.e. state photo studios, were independently supplied by the Office for Sales of Photographic Materials’. 15

These facts are important to mention because the transformation of the structure of the photographic market caused mayor shortages of supplies which, in turn, resulted in a steep decline in the local amateur photographic movement. 16 Photographic production is strictly dependent on both the photo-optical market (i.e. production of cameras) and the photo-chemical market (availability of the development process) and therefore cannot be considered without these. The materials manufactured by Polish producers were often defect due to structural problems in whole Polish production industry at the time: irregular deliveries, poor quality products, lack of automated production and unqualified workforce. 17 They were not only of poor quality, but also scarce in quantity. In autumn 1954 the Echo Krakowa daily wrote that there were only three specialist stores in town and moreover that they ‘scare customers with empty shelves and shop windows. Only sporadically do they have in stock a negligible amount of bromide papers, a few packages of fixer, several packages of universal developing paper and that’s it’. 18

As for the production of photo optical equipment, from the 1950s Warszawskie Zakłady Fotooptvczne manufactured cameras: Druh (a cheap 6 x 6 box camera for teenagers, manufactured since 1951) Start (two-lens reflex camera 6 x 6, 1951) and Fenix (35mm camera, 1957) and Krokus enlargers. However, their production was unable to satisfy the market and had to be largely supplemented by imports from the USSR and the GDR. In 1971, foreign trade enterprises in the photographic industry amounted to 89.3 % of the market demand. 19

The amateur photographic movement in Poland relied on local ‘Photographic Societies’ (Towarzystwa Fotograficzne), which functioned in most polish cities and towns, associated in a Federation for Photographic Societies. The professional photographic movement in turn, was controlled by the Association of Polish Art Photographers, which was established in 1947. For visitors from the ‘West’, it seemed that the photographic movement in Poland was surrounded by great care on the part of the state. 20

As we read in 1968 issue of ‘Fotografia’ 21 monthly, a particular difference between the amateur photographic movement in socialist countries and in capitalist countries is that ‘in the latter, photographic organizations are indeed little more than hobbyist societies. The results achieved may have a serious artistic value and indeed attract many enthusiasts of the art of photography, but they do not face such extensively planned tasks and functions of social upbringing, as is the case in socialist countries.’ 22 The quote, which illustrates the particularity of the Polish context, comes from a text ‘Reflections on social work’ (‘Refleksje na temat pracy społecznej’) by Krystyna Łyczywek, one of the most prolific Polish women photographers of the second half of the XX century, who regularly published in ‘Fotografia’ monthly.

Photographing children

Krystyna Łyczywek’s professional career began with a series of photographs of her son Włodzimierz. Five of these photographs titled ‘Study of a Child’ were featured at the first nationwide photo exhibition in Szczecin, organized at the turn of 1948 and 1949, on the occasion of the 25th anniversary of the Photographic Circle of the Polish YMCA Center. After this exhibition Łyczywek started presenting her work widely until in 1964 she was admitted to the Association of Polish Art Photographers.

Photographs of children were a common first step on the path to recognition for several other female photographers in Poland. Janina Gardzielewska became known after her exhibition Dzieci [Children] in 1960 in Toruń, and her pictures of pregnancy and maternity were among those most highly praised by the critics - to quote one of the reviewers from the period: ‘The picture ‘Pregnant’ is certainly a masterpiece: a beautiful figure of a woman with a calm expectation etched on her face, hands folded with gentle care on her bosom’. 23

Even Zofia Rydet, one of the most outstanding Polish photographers and author of the monumental documentary series ‘Sociological Record’, began her career with photographs of children. In the 1960s, she realized a series of works titled ‘Little Man’, shown at several individual exhibitions, and in 1964 released in an album. For the author, who had no children herself, the topic of the child - next to that of motherhood and old age - occupied a special place. The photographs for the Little Man series were taken in Poland and during trips to Albania, Bulgaria, Yugoslavia, Egypt, Libya, Lebanon, Italy and Czechoslovakia. As Alfred Ligocki wrote in the entry to the album, ‘the photographs by Zofia Rydet will not only teach us – sufficient to make of them a useful aid to psychologists, educationists and parents. The photographer not merely watches children: she also – and above all – loves them. And this emotional approach is visibly reflected in every one of her photographs’. 24

Following Thomas Galifot’s argument, one could conclude that the predominance of images of women and children in the work of women photographers reflects their long confinement to the domestic context. Celebrating the emotional ties between women, extolling maternal feelings, and, through this, the social role of mothers, capturing the charm of childhood – for decades these were often the motives at the heart of the artist photographer’s strategy to gain recognition. 25

At home with the camera

I spent the spring of 2020 at home with my child and a camera. It was the time of the global lockdown. However, because my son was only a baby at the time, I had already been ‘outed’ from social life and confined to the domestic sphere for over a year when the pandemic started. However, during the pandemic, I found a way to relate to this situation in a creative way: when the lockdown began, I grabbed the unexposed films, analogue and pinhole cameras which I could find at home, and started a daily routine of taking a picture of myself and my son every morning after waking up. In this way I created a series of over 40 domestic self-portraits with a child. One could say that, when playing at home during the pandemic with a child and a camera, I repeated the historical gestures of women who – hundred years earlier – tied to the domestic sphere and its codes, through the medium of photography, would challenge the same codes and spheres. Last year I exhibited some of the photographs from this series as part of a larger project titled Cherish, which problematized photography as affective labour.

Simultaneously another event took place during the pandemic, which seemed to turn the clock backwards by generations. In Poland, women’s reproductive rights have again become entirely restricted. A wave of social discontent swept through the country, but we could not express it directly because women had to remain locked in their homes. So we turned to cyber-activism and with the help of photographic self-portraits created a space of virtual mass protest on social media platforms. Participation in protest was executed by taking a picture of oneself and posting it online with the appropriate hashtag, using the structure of social media as a space for public manifestation. Such form of protest saw its peak in 2015-2016, with a wave of campaigns in which photography enabled many social groups new forms of participation in the public sphere, such as #MeToo, #TimesUp, and #BlackProtest, which turned public articulation of experiences of weakness, trauma and harm into a powerful social movement. Tens of thousands of women had published online photos of themselves holding a paper with the appropriate hashtag: each had the same agency because all the pictures counted, even if during the protest some received several thousand likes, and others only a few. The network made many women suddenly aware of the universality of their experiences that had previously seemed individual – experiences that had built a common margin. 26 To quote Anna Nacher: ‘the sum of many allegedly insignificant acts of sharing via social media eventually led to a mass collective action’. 27

For my research, this example is important because of the dynamics between the domestic space and the public space it illustrates and the role photography played in the reinterpretation of these two spheres. Especially during the second wave of the Black Protest in 2020, which took place under lockdown conditions, photographic cameras became tools of resistance at the moment of the ban on leaving the house. Selfies with appropriate hashtags have become an essential visual and performative manifestation of the practice of digital culture, which expresses participatory politics as a somewhat playful but at the same time serious intervention in the public sphere.

Dorota Walentynowicz ‘She-camera’, camera-objects 2021, exhibition view ‘Cherish’ Gdanska Galeria Miejska 2022

In response to these facts, I created a work titled She-camera, consisting of three camera-objects that operate analogously based on the working principle of camera obscura. These objects emphasize their own weakness - they are unashamedly imperfect and fragile, just as much as the photographs they take. However, the apparent weakness of the materials and the performance, which is unsuitable by today’s standards, allow for a specific kind of resistance to the technologically formatted tools of power. The camera-objects can thus function as independent entities, not subject to classification and recognition and therefore immune to capture, while at the same time playing the role of a prosthesis, mask or even armour, cooperating closely with the photographic subject as a co-shared organism. 28

Conclusion

The association between women, the camera and the domestic sphere seems to transverse the history of photography. In the early years of the development of the medium, women – whose activities were limited to seemingly unimportant home tasks – used photography to create domestic archives and write their micro-history, often challenging the social roles imposed on them. In this case, social control mechanisms were enhanced by Kodak’s advertising campaign launched around 1915 under the slogan ‘At Home with the Kodak,’ which illustrates the trend in Kodak advertising to position American women as domestic camera operators. In Poland after WWII, structural restrictions in photographic production made amateur photography a rare activity, subjecting it almost entirely to the social control of Photographic Societies. Under these circumstances taking on domestic subjects remained a way for women to gain recognition and access to photographic careers. Finally, in the last years, domestic forms of activism with the use of photography enabled many subaltern social groups – including women protesting against the ban on their reproductive rights – new forms of participation in the public sphere.

- The term women is each time used by me according to its placement within time-specific discourses. ↩︎

- Kamal Munir, Nelson Phillips, ‘The Birth of the ‘Kodak Moment’: Institutional Entrepreneurship and the Adoption of New Technologies’, Organization Studies, Vol. 26, Issue 11 (2005). ↩︎

- Nancy Martha West, Kodak and the lens of nostalgia, Virginia: University of Virginia Press, 1999, 53. ↩︎

- Colin Harding, ‘The Kodak Girl, Photographic World, 78, (1996). ↩︎

- Małgorzata Radkiewicz, ‘The Kodak Girl on a trip : tourist women from Polish Galicia in family photographs of 1910s -1930’, in: Sabina Owsianowska, Magdalena Banaszkiewicz eds., Anthropology of Tourism in Central and Eastern Europe: Bridging Worlds, New York and London: Lexington Books, 2018, 297. ↩︎

- Ibid., 29. ↩︎

- Ibid., 305. ↩︎

- Jürgen Habermas, who developed the concept of the public sphere, claimed that this sphere originated in 18th-century Europe as a space for critical discussion and links the emergence of the public sphere (Öffentlichkeit) with the development of capitalism. According to Habermas, public sphere is a space outside state control where individuals exchange views and knowledge. Prior to the 18th century, European culture was dominated by a „representative” culture where only one side claimed the right to represent itself. Jürgen Habermas Strukturwandel der Öffentlichkeit. Untersuchungen zu einer Kategorie der bürgerlichen Gesellschaft Neuwied/Berlin 1971 [1962]. The Habermasian model of the public sphere was discussed and deconstructed by feminists philosophers such as Nancy Fraser, as a non existing ideal of pure deliberation. ↩︎

- Marianne Hirsch, Family Frames: Photography, Narrative, and Postmemory, Cambridge and London: Harvard University Press, 1997, 47. ↩︎

- Susan Mogul, in the catalogue of the exhibition What Becomes a Legend Most?, Zachęta National Gallery of Art, Warsaw, 5.08- 30.10.2022. ↩︎

- Kamal Munir, ‘The rise and fall of Kodak’s moment,’ University of Cambridge website, on-line article, 14th Mar 2012, https://www.cam.ac.uk/research/news/the-rise-and-fall-of-kodaks-moment, (accessed: 9th April 2022). ↩︎

- Biography of Goldberg Maksymilian at https://www.warszawa1939.pl/osoba/osoba-goldberg-maksymilian-201 ↩︎

- Barbara Klich-Kluczewska, ‘Luxury from the USSR and the GOR? Cameras and Photographic Equipment as Official and Unofficial Objects of Trade in the PRL’, in: Marek Maszczak ed., Sdelano w SSSR. Soviet Photographic Cameras, Kraków: Muzeum Historii Fotografii, 2015, 16. ↩︎

- Małgorzata Czyńska, Katarzyna Gębarowska, Kobiety Fotonu [Women of Foton], Bydgoszcz: Wydawnictwo Farbiarnia, 2018, 26. ↩︎

- Quoted in Klich-Kluczewska, 22, from S. Chaskielewicz. Sprzedaż artykułów fotograficznych [Sale of photographic items], Warszawa 1956, 5. ↩︎

- Anon., ‘O zaopatrzeniu rynku w artykuły fotograficzne’ [About supplying the market with photographic articles], Fotografia, 1 (1955), 2. ↩︎

- Anon, ‘Wady materiałow fotograficznych’ [Defects in photographic materials], Fotografia 5 (1955), 8-9. ↩︎

- Echo Krakowa, 4th November 1954, 6. ↩︎

- Anon.,‘ Zakup towarów przez przedsiębiorstwa handlu rvnkowega a przedsiębiorstwa handlu zagranicznego’ [Purchase of goods by commercial and foreign trade enterprises], Rocznik statystyczny handlu wewnętrznego, No 58, GUS, Warszawa 1972, 98. ↩︎

- Krystyna Łyczywek, ‘Wizyta Rolanda Bourigeaud w Polsce’ [Roland Bourigeaud’s visit to Poland], Fotografia, 11, (1965). ↩︎

- Fotografia was a monthly magazine published between 1953 and 1974 by the Association of Polish Photographers. ↩︎

- Krystyna Łyczywek, ‘Refleksje na temat pracy społecznej’ [Reflections on Social Work], Fotografia, 8 (1968). ↩︎

- Głos Olsztyna, daily, 16th March 1963. ↩︎

- Alfred Ligocki, ‘An Introduction to Zofia Rydet Mały człowiek’, [ Little Man],Warszawa: Arkady, 1965. ↩︎

- Marie Robert, Ulrich Pohlmann, Thomas Galifot, Qui a peur des femmes photographes ?, Paris: Hazan, 2015, 8. ↩︎

- Elżbieta Korolczuk, Beata Kowalska, Jennifer Ramme, Claudia Snochowska-Gonzalez eds., Bunt kobiet. Czarne Protesty i Strajki Kobiet [Women’s rebellion. Black Protests and Women’s Strikes], Gdańsk: Europejskie Cenrum Solidarnosci, 2018. ↩︎

- Anna Nacher, ‘#BlackProtest from the web to the streets and back: Feminist digital activism in Poland’, European Journal of Women’s Studies, Vol. 28, Issue 2 (2020). ↩︎

- Dorota Walentynowicz: Cherish, exhibition curated by Anna Ciabach at Gdańska Galeria Miejska, 1. 07- 04.09. 2022. ↩︎

Dorota Walentynowicz

Dorota Walentynowicz, is a visual artist, curator and educator, and a graduate of the ArtScience Interfaculty (KABK, The Hague) and the Faculty of Photography (University of the Arts Poznań). She received her PhD from the Academy of Fine Arts in Gdańsk. The area of her artistic and theoretical interest concerns photography understood not only as a means of creating and distributing images, but above all as a form of research and deconstruction of the process of seeing and being seen. Much of her current activity is connected with collective practices that aim to develop horizontal and heterarchical methods of functioning within the existing models of artistic production.