Title

Voices of Freedom Exhibiting Polish Women Artists in the Time of Transition

https://doi.org/10.48285/ASPWAW.29564158.MCE.2024.10.2

Poland, political transition, all-women exhibition, feminism, National Museum in Warsaw, National Museum of Women in the Arts

https://miejsce.asp.waw.pl/en/voices-of-freedom/

Abstract

In September 1991, the exhibition „Polish Women Artists”, curated by Agnieszka Morawińska, opened at the National Museum in Warsaw. A few weeks later, a smaller version of the show, titled „Voices of Freedom: Polish Women and the Avant-Garde, 1880–1990”, opened at the National Museum of Women in the Arts in Washington, DC. In this article, I discuss the development of the idea behind both exhibitions, the form they assumed, and their critical reception. I focus on how they reflected a particular moment in Polish history, namely, the first years of the political and economic transition and the situation of women at the time. Focusing on „Polish Women Artists,” I present then-current ideas about the relationship between art and (feminist) politics and how these influenced the understanding of feminist art history and museology in Poland. My subsequent analysis of the „Voices of Freedom” exhibition reveals a different background of the interest in Polish women artists expressed in the United States at the time.

Keywords

Poland, political transition, all-women exhibition, feminism, National Museum in Warsaw, National Museum of Women in the Arts

DOI

In the documentary 1993, women active in Polish public life during the transition to democracy tell that they were surprised, even shocked, by the nature of the changes, especially by their anti-feminism.1 Małgorzata Fuszara recalls how women believed – naively perhaps, she adds – that gender equality would come naturally with democracy; consequently, the proposal of a law limiting women’s reproductive rights came as a disappointment. Women realized they were being ignored in public debates, and their contributions to recent historical developments were erased. It soon became clear that the negative consequences of the transition to a liberal economy, including the collapse of the welfare system and several industrial sectors, were felt primarily by women. When summarizing the situation of women ‘after communism’, Elżbieta Matynia titled her text ‘a bitter freedom’, which reflects the disillusionment of that time2. At the same time, the biggest exhibition (to date) of Polish women artists was taking place at a major art institution in Warsaw. In September 1991, Polish Women Artists, curated by Agnieszka Morawińska, opened at the National Museum. A few weeks later, a smaller version of the show, Voices of Freedom. Polish Women and the Avant-Garde, 1880–1990, opened at the National Museum of Women in the Arts (NMWA) in Washington, DC. In the present text, I explain how these exhibitions were conceptualized, the form they ultimately assumed, and their critical reception, revealing how they mirrored the political transition and the situation of women at the time.

Polish Women Artists

In my conversation with Agnieszka Morawińska, she stated directly that she brought the idea for the Polish Women Artists exhibition from the United States.3 Morawińska had worked for the National Museum in Warsaw since 1976 and had an established position as the chief curator of the Gallery of Polish Art.4 She also had many international contacts resulting from her research stays abroad and Polish art exhibitions curated by herself (e.g. Polnische Malerei von 1830 bis 1914 in Cologne and Symbolism in Polish Paintings 1890-1914 in Detroit). Her interest in women’s art increased during her stays in the United States in the second half of the 1980s. As she recalls, during one of them, ‘In a few weeks, I toured sixteen university and museum centres and got to know the entire art-historical world.’5 During conversations at this time, the idea for an art exhibition featuring Polish women artists – the equivalent of Women Artists: 1550–1950 (curated by Ann Sutherland Harris and Linda Nochlin), which was held in 1976 at the Los Angeles County Museum of Art – was born. In her introduction to the catalogue for Voices of Freedom, Morawińska thanked several people who helped her explore women’s art and the feminist history of art, including Julia Henshaw of the Detroit Institute of Arts, who ‘directed her to the subject of art created by women and suggested some important books on the subject’; Diane Russell of the National Gallery of Art in Washington, DC, who ‘provided invaluable guidance on feminist literature’; Mary Garrard, who ‘provided bibliographical information and encouragement’; and Marjorie Lightman, who ‘generously gave me her collection of books on women.’ What might be termed feminist research developed in state-socialist Poland in several academic domains but not in the field of art, which remained a reserve of patriarchal assumptions. Feminist issues were present in the art of women artists, at first independently of second-wave feminism, then in dialogue with it. They were also visible in some exhibitions these artists organized, but the latter focused on the current moment and did not have historical ambitions. To the best of my knowledge, the only art-historical publication devoted to women artists was Alicja Okońska’s Polish Women Painters (1976),6 where the author examined the various attitudes of women artists concerning ‘the reconcilement of artistic activity with every woman’s need for love, the desire to start a family.’7 The book bears no traces of an emancipatory discourse. This was also true of other studies of women artists, such as Helena Blum’s numerous texts on Maria Jarema and Olga Boznańska. As Hussakowska and Smolińska observed, Blum directed her attention towards women artists she admired but considered their art through the lens of modernist art history, where categories such as genius or originality and questions of form played a crucial role.8 While some critics occasionally referred to foreign historical exhibitions presenting women artists (e.g. Morawski wrote about Kunstlerinnen International 1877–1977), their observations did not resonate in art-historical and museum circles, where a feminist perspective was all but absent.9 In this context, Polish Women Artists may be seen as an example of the late importation of second-wave feminism into the country. The concept of a historical show of women artists found fertile ground in Poland only when a new form of feminist discourse started to develop here more intensively. This discourse dissociated itself from socialist emancipation coupled with the communist regime, instead turning towards North American thought combined with liberal democracy.

Morawińska’s intention was the same as Harris and Nochlin’s: to restore forgotten women artists to the art-historical narrative and encourage further studies. In the catalogue for the show, the curator stated, ’ The simplest and most obvious rationale for preparing this type of exhibition is cognitive curiosity.’10 Extensive research resulted in the first comprehensive historical overview of art produced by Polish women artists. The exhibition featured works by more than 200 artists from the eighteenth to the twentieth century. For the earlier periods, every woman artist who could be identified was included, but this was not possible for the sections on modern and contemporary art. Here, Morawińska sought the advice of Kinga Kawalerowicz, a Warsaw critic and curator. Morawińska claimed that they wanted to include artists whose works contained any feminist element. As she explained in the catalog, ‘Thus, we can talk about women’s art only in our modern times – when the subject of art becomes the artist’s own existential experience; at this point and only then does the significant genre difference of women’s art appear.’11 The content of the work was not, however, the most critical aspect; rather, Morawińska concentrated on the artists’ careers. For example, in the biographical notes, she wanted to include information on the artists’ families because this was a more important factor in their career development than men’s.12 The exhibition catalogue, essentially the first and only monograph of women’s art created in Poland, was – like the exhibition itself – the fruit of extensive research. The central part of the catalogue consisted of biographical notes, each supplemented by a short bibliography, a list of exhibitions, and a small selection of reproductions of the artists’ works. This section was preceded by three articles: a history of Polish women artists, focusing on how their position in the art world had changed (by Morawińska); a study of culturally active women in the nineteenth century (by Waldemar Okoń); and a history of feminist art history (by Maria Poprzęcka), where the author stressed the significance of traditional biographical research - an example being the exhibition catalogue itself – and how a feminist perspective encouraged one to rethink ‘the fundamental questions about art and its values’. Although she was sympathetic towards feminist interventions in art history, she criticized them for their ‘viciousness, often unbearable rhetoric, lack of self-criticism, a fervour for fighting for the “only right” women’s cause, and easily succumbing to current methodologies and ideologies’.13 Poprzęcka’s position, which was probably based on her understanding of the appropriate relationship between academia and politics, corresponded with Polish art discourse at the time. As Jakub Banasiak observed in Proteuszowe czasy, it was believed that the separation of art and politics might finally be possible.14 The author convincingly argued that this was the result of two interrelated tendencies, namely, a local reaction to what Andrzej Turowski called ideoza (the submission of all aspects of life to politics in post-totalitarian society) and postmodernism, which lacked ideological depth and political commitment. The exhibition Polish Women Artists cannot be described as postmodernist; indeed, it resulted from a commitment to and belief in change, even if this change was a greater knowledge of women artists. It did, however, share a tendency on the part of artists, art historians, and curators not to engage politically or ideologically. Polish Women Artists manifested an idea that emerged and flourished in the United States and Western Europe in the 1970s. For this reason, it has often been called ‘late’. In this text, I will not analyze why it could not have been done earlier. But I want to think about this specific moment that, in my opinion, was particularly suitable for realizing such a project, maybe the only possible. Talking about this exhibition today, Morawińska said, ‘There was momentum’.15 She underlined that everything was changing, and new ideas and initiatives appeared. This ferment was also visible in the second half of the 1980s among feminists. Feminist cultural, academic, or activist meetings started to be held in different Polish cities, and interregional networks emerged.16 Those responsible for these grassroots initiatives distanced themselves from state-controlled organizations, opposing state politics, and associated themselves with the political opposition. These initiatives created an excellent context for an exhibition concentrating on women artists, but the bottom-up nature did not provide sufficient sources to realize the big project. This was apparent in an example of an exhibition of Warsaw women painters at the Dziekanka Gallery in 1987.17 Such an institution as the National Museum was probably the only one – with the necessary capital and stable enough in those unstable times – to fulfil Morawińska’s vision.

As many women soon began to claim, one of the aspects of the transition to democracy was a return to ‘normal’, meaning traditional gender relations that had been destabilized during the state-socialist (called ‘communist’) period. This manifested itself most clearly in the rapid attempt to introduce restrictions on reproductive laws and to remove women from the political space. Elżbieta Matynia, a sociologist based in New York, wrote in the above-mentioned text, ‘When I first returned to my native and already virtually “post-Communist” Poland in the summer of 1989, after an eight-year absence, one of the things that struck me most vividly was that in the new and exuberant public life of the country there was an almost total absence of those capable women who had played such an active and essential role in the clandestine operations of the pro-democratic movements of the 1970s and 1980s.’18 Realizing an ambitious project focusing on women, such as Morawińska’s, seems impossible in the period when women were being erased from recent history and made to feel unwelcome in political life. Not long after, it would have been. The key thing for making this project happen was, in my opinion, that it started before 1989 when the transition was imagined differently. The position of Morawińska, who then became a deputy minister of culture, also played an important role. As well as the opportunity to show the exhibition in the United States, which will be discussed in the later part of the text. Agnieszka Morawińska used her capital to realize the idea of the exhibition that concentrated on women artists, showing how plentiful and accomplished women artists were and how their situation changed through the ages, including how they struggled to occupy important subjective positions within it.

At this particular moment when the exhibition opened – 1991 – it could have been an important political gesture, but it was not recognized as such. The curator herself did not stress this aspect of the show. Perhaps she did not realize that the political situation had changed during the realization of the exhibition and that in the new context, the exhibition might be more significant if it was framed in the context of gender politics rather than art history.

The exhibition was noted in feminist circles, but as Ewa Toniak wrote, it did not move ‘Polish feminists’ theses’; it was treated as ‘another lecture’ that was no more than ‘interesting’.19 Toniak’s text on the exhibition was included in the first collection of feminist articles published in the 1990s, but the show, which featured no feminist art – or at least failed to highlight the feminine aspects of the works – triggered no further discussion amongst feminists. Its objectives did not seem to be a priority during a period dominated by reproductive rights issues.20 Additionally, women artists were not particularly keen to support the women’s movement. The return to traditional gender relations discouraged many women artists from engaging in women’s issues, particularly in a more combative way. It was to change in the following decade with the development of so-called critical art. The reception of Polish Women Artists demonstrated little understanding of why it came about. The critics were not driven by a dislike of women’s art; rather, they stressed that the works did not share any features, so there was no point in putting them together in one show. An article published in Trybuna remarked sardonically that ‘one should basically treat the notion of women’s art as if the criterion for the selection of exhibits was, for example, the amount of greenery used in the painting’.21 In turn, Paweł Bravo focused on the lack of ‘feminine elements’ and claimed that searching for any other distinguishing features would be in vain.22 He added that one could compare the ‘invention and possibilities’ on display in the exhibition favorably with ‘the imaginatively constructed state of “masculine” art of the twenties and thirties’. Bravo concluded that art should be liberated from the division between female and male artists, and the exhibition, paradoxically, might help to achieve this. These and other critics expressed their lack of understanding of the show’s governing idea, though some noted that the exhibition demonstrates how the status of women artists and their capacity to function in the art world had changed. For example, the author of the Trybuna article commented that ‘women artists, who usually took family responsibilities seriously, struggled against limitations’. Monika Małkowska, in turn, reacted negatively to the suggestion that Polish Women Artists was a feminist exhibition: ‘What the hell does feminism have to do with good, sometimes outstanding art?’ But she too was aware of the problems women artists face, claiming that the lack of restrictions on the development of their careers is theoretical and that ‘the stairs start after the diploma, unless the choice of field of study is applied arts.’23 In many reviewers’ eyes, these observations were insufficient justification for staging the exhibition. The exhibition’s reception reflected the expectations many had of museums; the time for critical museology was yet to come. Few of those who wrote about Polish Women Artists understood the concept of feminist museology. Two exceptions were Ewa Toniak and Joanna Sosnowska. The former situated the exhibition against a backdrop of feminist art history, whereas the latter initiated a discussion around certain curatorial decisions, for example, asking how Morawińska might have better addressed the matter of women’s art. Sosnowska questioned Morawińska’s decision to place the works in chronological and alphabetical order, arguing that this was a ‘male’ way of writing history and that a thematic approach would have been more appropriate.24 Giving an example of a different approach of women to various genres, she described how artists constructed space in their paintings. Toniak’s and Sosnowska’s comments demonstrate that even if feminist art history was not developed in Poland, some scholars showed interest in and understood it. Both averred that they had only recently begun familiarizing themselves with feminist texts.25 One of Toniak’s remarks highlighted a significant aspect of feminist discourse in 1990s Poland (and Eastern Europe generally): ‘one can see that the exhibition Polish Women Artists was not a feminist import into a country where there was no feminist underground, but a reference to a tradition that had been broken after the war.’ Indeed, the catalogue contained two appendices: one, a list of schools where women could study art before being allowed to enter public art academies, and the other, a list of all-women exhibitions. The latter included only pre-World War II shows alongside a statement that ‘The tradition of organizing collective feminist exhibitions did not survive in post-war Poland’.26 Writing on the development of feminism in Eastern Europe, literary scholars Anna Artwińska and Agnieszka Mrozik claimed that ‘After the stage of establishing the ties – of spiritual daughterhood or sisterhood – with the so-called “second wave” of Western feminism, the contemporary women’s movements in this part of the world began to anchor themselves deeper in the national traditions of the countries in which they respectively function. […] These genealogies welcome the advocates for women’s rights from before state socialism’.27 In the case of Polish Women Artists, both perspectives met: orientation towards Western feminist art history and pre-war local tradition. The latter did not concern art history writing on or by women but still created the impression that the project might have had predecessors in the pre-war tradition of initiatives relating to women artists. In a way typical of this period, informed by strong anti-communist sentiment, the organizers of Polish Women Artists ignored the emancipatory aspects of state-socialist Poland. This is interesting, as probably the high-level understanding of the social problems encountered by women artists that were discussed in the exhibition catalogue and reviews may have resulted from the intensive presence of socialist emancipatory discourse in the previous decades. Disregarded by post-socialist feminists as having been used by the totalitarian government and the ruling communist party, it might nevertheless have borne fruit. Joanna Sosnowska noted this disapprovingly in another text dedicated to the exhibition. She wrote, ‘feminist slogans never became very popular in Poland, although, after all, they grew up on the leftist ground, which, despite all reservations, can be felt when reading the catalogue catalogue. […]. The spectre of “class struggle” hovers over it.’28

Voices of Freedom

The idea for an exhibition of Polish women artists in the National Museum of Women for the Arts arose in the United States independently of the organization of Polish Women Artists. Blanka Rosenstiel, the president of the American Institute of Polish Culture founded in 1972 in Miami, was behind this initiative. One of the two aims of the institute was ‘to share with Americans the rich heritage of Poland, which has contributed in so many ways to the history of the U.S.’29 In her introductory note to the catalogue for Voices of Freedom, Rosenstiel wrote about her dream of bringing the work of Polish women artists to the United States, which finally came true.30 As archival documents indicate, Rosenstiel contacted the NMWA (founded by Wilhelmina Cole Holladay and her husband Wallace F. Holladay) in 1986, a year before it officially opened.

Wilhelmina Cole Holladay stated in an interview that when she and her husband were thinking about how to focus their collection, they saw and admired paintings by Clara Peeters and realized how little she and other female artists were known.31 From that point, the Holladays began acquiring work by women artists. This brought them to the decision to establish in 1981 a museum dedicated solely to them. In 1982, they bought a building in downtown Washington, DC, that required extensive renovation. The museum finally opened in April 1987, with an inaugural exhibition titled American Women Artists: 1830–1930. The museum continued with presenting group shows featuring American women artists from particular regions, such as Separate but Equal: Ohio Women Artists (1990) and A Personal Statement: Arkansas Women Artists (1992). They also decided to exhibit art created by women artists from outside the country; Holladay later explained that her diplomatic career was essential in realizing this plan. The first exhibition of this type was Three Generations of Greek Women Artists: Forms, Figures, Personal Myths (1989). According to Holladay, it was the outcome of a meeting at the Greek Embassy in Washington, DC, with Melina Mercouri’s brother, who was the Minister of Culture.32

When Blanka Rosenstiel received confirmation from the NMWA that they were interested in organizing a show, she sent a colleague in 1988 to Poland to study women artists.33 It was then discovered that Agnieszka Morawińska had already worked on a similar one. It’s when the first ideas of cooperation must have appeared. In the autumn of 1989, Morawińska received a letter confirming that the NMWA was enthusiastic about staging a smaller version of the original.34 In September 1989, Wilhelmina C. Holladay went to Poland, visiting Warsaw, Cracow, and Łódź. Here again, Blanka Rosenstiel played a crucial role as she established the ‘VIP Visitor Program’ (through the Polish Arts and Culture Foundation); Holladay was the first American museum director to participate.35

Holladay kept a journal during her stay in Poland. It is a fascinating report of a foreigner approaching life in Poland and Polish cultural institutions in this turbulent period.36 For example, she commented on how things were organized (‘The system is dreadful’, ‘nothing is easy’, and ‘everything lasts forever’) and the economy (‘Everything with prices is crazy’ and ‘the economic chaos has everyone nervous’). Morawińska, whom she had met briefly in Washington, DC, accompanied her during some of the events, probably the most important being Holladay’s visit to the National Museum in Warsaw. After that, Holladay wrote, ‘I was given a wonderful tour of the museum and a special lunch. Agnieszka had arranged for me to be introduced to each department head and see what works by women were being prepared for the show. This was of great interest to me and I very much enjoyed my time with those very informed scholars.’ On her side, Agnieszka Morawińska wrote to Holladay that her visit ‘gave a new motivation to work on the show of Polish women artists.’37 They met again in November 1990 (a year later), when Morawińska went to Washington, DC, for a preparatory visit financed by the Kościuszko Foundation.

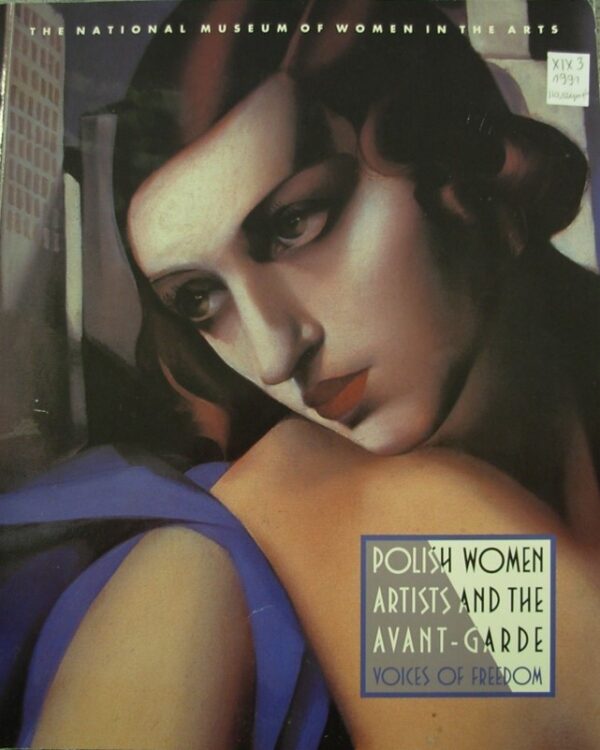

After contact was made with Morawińska, the American exhibition of Polish women artists was discussed as a limited version of her Warsaw show. Although the agreement between both institutions stated that the National Museum in Warsaw was responsible for the exhibition concept, some documents show that the NMWA at least proposed some crucial solutions, for instance, that the exhibition should focus on art from the late nineteenth century to the present day and should present ten to twelve artists so that more of their work could be displayed.38 They also sent a list of artists who – based on the material available – were ‘particularly impressive.’ The final list of artists exhibited was slightly different and longer; it included Magdalena Abakanowicz, Anna Bilińska-Bohdanowicz, Olga Boznańska, Elżbieta Felicyta Chachaj, Izabella Gustowska, Maria Jarema, Katarzyna Kobro, Zofia Kulik, Ewa Kuryluk, Tamara de Lempicka, Mela Muter, Teresa Pagowska, Maria Pinińska-Bereś, Elżbieta Sikorska, Zofia Stryjeńska, Alina Szapocznikow, and Maria Tyniec. Later on, the NMWA suggested the title Voices of Freedom: Polish Women Artists and the Avant-Garde. 1880–1990 as ‘accurately reflecting the exhibition’, but proffered no further explanation why.39 The title change – which Morawińska accepted without reservation – was important because it indicated how the artists would be presented at the Washington show.

Voices of Freedom: Polish Women and the Avant-Garde, 1880-1990, 1991, The National Museum of Women in the Arts in Washington, DC, exhibition view, the archive of the National Museum of Women in the Arts

Danuta Wałęsa, the wife of then-President Lech Wałęsa, wrote the foreword to the catalogue. In the introduction, Kazimierz Dziewanowski, ambassador to the Republic of Poland, referred to the growing interest in Poland and its culture after the emergence of the Solidarity movement; in his words, this had ‘currently intensified’40 He underlined the necessity of going beyond current political and economic issues to appreciate the richness of Polish culture but, at the same time, placed the exhibition in the context of the recent past. It was, he argued, ‘not only a major artistic event but also a manifestation of the ability of the human spirit to overcome practical obstacles and difficulties to reach that higher sphere of cultural values that is common to all people, without which our best-intentioned efforts at building democracy and prosperity would be incomplete and deficient.’41

Other texts in the introductory section of the catalogue spoke of the contribution of Polish women artists to international cultural heritage. They also stressed the issue of freedom and its restrictions, referencing Poland’s political situation. The latter is presented as an obstacle in these artists’ presence in the US and, more generally, abroad. The same message was conveyed via the wall text:

[…] Polish art has received very little attention in the United States over the past century. Indeed, it is only in the last few years, with our recognition of the independent Solidarity trade union movement and the precipitous decline of the Soviet Union’s influence, that many Americans have come to appreciate the importance of Poland’s existence as a free and independent nation. Given our recent awareness of and support for the immense political and cultural changes underway in the Eastern bloc, this seems a particularly relevant moment to present the artistic legacy of the last one hundred years of Polish art.42

Paradoxically, many of the women artists in the exhibition spent significant periods of their artistic lives outside Poland, which was not commented upon. Tamara de Lempicka, for example, whose work was featured on the cover of the catalogue (probably because she was the most well-known artist in the show), enjoyed her greatest success when she was living in Paris; Polish museums house very few of her paintings.

Cover of the Voices of Freedom: Polish Women and the Avant-Garde, 1880-1990, catalog, 1991, The National Museum of Women in the Arts in Washington, DC

Many press titles mentioned the exhibition, but few interesting texts were written. Most repeated fragments from the press release, with the following sentence making several appearances: ‘[The artists’] names have become nearly synonymous with a movement or medium. […] No discussion of Constructivism - […] - is complete without the mention of the outstanding art of Katarzyna Kobro.’43 More interesting texts developed the idea proposed by the museum that the exhibition related directly to Polish history. This was most evident in Hank Burchard’s Washington Post article.44 It began thus: ‘In retrospect, it seems inevitable that Poland was the hot spot where the Cold War thaw began.’ Burchard claimed that women’s ‘struggle for self-government of their country and themselves is the subject of Voices of Freedom’, which seems to go beyond what was intended by the museums involved. To support his argument, Burchard also falsely claimed that Morawińska had ‘been working on this show almost since the day her country became free.’ Megan Hamilton’s observation was similar but more nuanced: ‘Poland’s location on a flat plain in the centre of Europe has left her under an almost constant state of siege. […] This experience has informed work in Voices of Freedom: Polish Women in the Avant-Garde, 1880–1990, which often refers to oppression. […] Forsaking melodrama, the artists have explored the violence of the theme subtly and obliquely, making the end effect especially poignant.’45 She pointed out that while Poland was associated with Cold War isolation, the works in the exhibition were not of provincial artists; many had international connections.

Both the texts prepared by the Voices of Freedom organizers and the reviews all but ignored significant aspects of the original exhibition. None of the writers mentioned the feminist argument that patriarchal society made it difficult for women artists to pursue their careers or that patriarchal art histories rendered them invisible. This was understandable considering the development of feminist art history in the United States – what was a new perspective in Poland belonged to the history of feminist scholarship in this country. And at that time, one did not expect that scholars from such a country as Poland could bring a new perspective to the development of feminist art history. Besides, the latter had no such ambitions. Also, the history of the ‘obstacle race’ Polish women artists were compelled to participate in was not likely to be of interest to an American audience other than in terms of a general enthusiasm for change in Eastern Europe. In other words, what mattered was the current political situation.46 But this was perceived selectively: discussions around the exhibition did not refer to the impact of the transition to democracy on Polish women.

The title of the present study refers to the Washington show (Voices of Freedom), but as my analysis has revealed, the phrase is used somewhat ironically. The transition to democracy and liberal economics brought women but ‘bitter freedom’. The ideas of both exhibitions were conceived independently during the final years of the Polish People’s Republic, when there was a degree of excitement and optimism. Yet, the idea was finalised in the exhibition already in the period when it was clear that, at least as far as women’s issues were concerned, the transition was characterized by regression into ‘normal’ (i.e. traditional) gender roles and relations. The art world distrusted ideologically driven artistic and curatorial gestures, and feminist ideas developed slowly. Polish Women Artists, in many ways, reflected the complicated nature of feminist thought and practice in the early transition period. In turn, the Washington version proved that outside the country - even in an institution explicitly dedicated to women artists - Polish women artists could not count on the deep interest in the specificity of their situation and experiences. The exhibition presented their work just as emblematic of Polish history and the political changes taking place. Meanwhile, the voices of those who might have spoken about freedom and the limitations thereon were nowhere to be heard.

This text is based on research funded by the Polish National Science Centre (nr. 2020/39/B/HS2/00443)

Bibliography

Artwińska, Anna, and Agnieszka Mrozik, ‘Generational and Gender Memory of Communism in Central and Eastern Europe. Methodological Perspectives and Political Challenges’, in Gender, Generations, and Communism in Central and Eastern Europe and Beyond, ed. By Anna Artwińska and Agnieszka Mrozik (New York: Routledge, 2021), pp. 9-28

(BZ), ‘Sztuka i sztuka kobiet’ [Art or art of women], Trybuna (21-22 September 1991)

Banasiak, Jakub, Proteuszowe czasy Rozpad państwowego systemu sztuki 1982-1993. Stan wojenny, druga odwilż, transformacja ustrojowa (Museum of Modern Art, Academy of Fine Arts in Warsaw, 2020)

Bravo, Pawel, ‘Sztuka nie ma płci’ [Art has no gender], Polityka, 39 (1991)

Burchard, Hank, ‘Poland’s Women Artist-Warriors’, The Washington Post (27 December 1991)

Dziewanowski, Kazimierz [n. title], in Voices of Freedom. Polish Women Artists, ex. cat. (Washington: The National Museum of Women in the Arts, 1991), p. 8.

Graff, Agnieszka, ‘Patriarchat po Seksmisji’ [Patriarchat after sexmission], Gazeta Wyborcza ( 19 June 1999)

Hamilton, Megan, ‘Sophistication not Isolation: Surprises from Poland’, Women’s Art Magazine, 42 (1992)

Holladay, Wilhelmina Cole, 17 August-23 September 2005. Archives of American Art, Smithsonian Institution. Oral history interview with Wilhelmina Holladay, 2005 Aug. 17-2005 Sept. 23 | Archives of American Art, Smithsonian Institution | Archives of American Art, Smithsonian Institution (si.edu) [accessed 12 May 2024]

Holladay, Wilhelmina Cole, A Museum of Their Own: National Museum of Women in the Arts (New York: Abbeville Press, 2008)

Hussakowska, Maria, ‘Helena Blum and Her Modern Art History – Written and Exhibited’ in Talking about Exhibition. An Anthology, ed. by Maria Hussakowska (Kraków: Jagiellonian University Press, 2012), pp. 106-123

Małkowska, Monika, ‘Nie feminizm’ [Not a feminism], Życie Warszawy (21-22 September 1991)

Matynia, Elżbieta, ‘Women After Communism: A Bitter Freedom’, Social Research, 61, 2 (Summer 1994), pp. 351-77

Morawińska, Agnieszka, ‘Artystki polskie’, in Artystki polskie [Polish women artists], ed. by Agnieszka Morawińska, ex. cat. (Warsaw: National Museum, 1991)

Morawski, Stefan, ‘Neofeminizm w sztuce’ [Neo-feminism in art], Sztuka, 4 (1977), pp. 57– 63

‘Nasze muzeum. Rozmowa z Agnieszką Morawińską’, www.dwutygodnik.com, 9 (2018) [accessed 12 May 2024]

Okońska, Alicja, Malarki polskie [Polish women painters] (Nasza Ksiegarnia 1976)

Poprzęcka, Maria ‘Inne? Kobiety i historia sztuki’ [Others? Women and art history], in Artystki polskie [Polish women artists], ex. cat. (Warsaw: National Museum, 1991), pp. 17-20.

Rosenstiel, Blanka [n. title], in Voices of Freedom. Polish Women Artists, ex. cat. (Washington: The National Museum of Women in the Arts, 1991), p. 9

Smolińska, Marta, ‘Helena Blum (1904-1984) - a Polish Art Historian in the Gender Gap’, Journal of Art Historiography (29 December 2023) smolinska.pdf (wordpress.com) [accessed 12 May 2024]

Sosnowska, Joanna, ‘Czytając katalog’ [Reading the catalog], Exlibris. Supplement to Życie Warszawy (17 July 1992)

Sosnowska, Joanna, ‘Na marginesie wystawy “Artystki polskie”’ [On the margins of the exhibition: Polish Women Artists], Twórczość, 9 (1992), pp. 123-26

Toniak, Ewa ‘Ach, te baby’ [Ah, these women], Obserwator, 58 (1992)

Walczewska, Sławomira, ed., Feministki własnym głosem o sobie [Feminists in their own voice] (Kraków: eFKa 2005)

- 2022, dir. Magdalena Mosiewicz, Magda Lipska, and Łukasz Ronduda. ↩︎

- Elżbieta Matynia, ‘Women After Communism: A Bitter Freedom’, Social Research Vol. 61, No. 2 (Summer 1994). ↩︎

- Conversation with Agnieszka Morawińska, 13 July 2022. ↩︎

- For more on Morawińska’s career, see ‘Nasze muzeum. Rozmowa z Agnieszką Morawińską’ [Our museum. A conversation with Agnieszka Morawińska], www.dwutygodnik.com, 09 (2018) [accessed 12 May 2024]. ↩︎

- Ibid. ↩︎

- In 1951, Stanislav August’s Female Painters was published by the wife of the author, Zygmunt Batowski, who was murdered in 1944. ↩︎

- Alicja Okońska, Malarki polskie [Polish women painters] (Warsaw: Nasza Księgarnia, 1976), p. 8. ↩︎

- Maria Hussakowska, ‘Helena Blum and her modern art history – written and exhibited’, in Talking about Exhibitions. An Anthology, ed. by Maria Hussakowska (Kraków: Jagiellonian University Press, 2012), 106-23; Marta Smolińska, ‘Helena Blum (1904-1984) – a Polish Art Historian in the Gender Gap’, Journal of Art Historiography, 29 December 2023 smolinska.pdf (wordpress.com) [accessed 12 May 2024] ↩︎

- Stefan Morawski, ‘Neofeminizm w sztuce’ [Neo-feminism in art], Sztuka, 4 (1977), pp. 57–63. ↩︎

- Agnieszka Morawińska, ‘Artystki polskie’, in Artystki polskie [Polish women artists], ed. by Agnieszka Morawińska, ex. cat. (Warsaw: National Museum, 1991), p. 9. ↩︎

- Ibid., p. 14. ↩︎

- Conversation with Agnieszka Morawińska, 13 July 13 2022. ↩︎

- Maria Poprzęcka, ‘Inne? Kobiety i historia sztuki’ [Others? Women and art history], in Artystki polskie [Polish women artists], ex. cat. (Warsaw: National Museum, 1991), p. 19. ↩︎

- Jakub Banasiak, Proteuszowe czasy Rozpad państwowego systemu sztuki 1982-1993. Stan wojenny, druga odwilż, transformacja ustrojowa (Museum of Modern Art, Academy of Fine Arts in Warsaw, 2020), pp. 524-29. ↩︎

- Conversation with Agnieszka Morawińska, 13 July 13 2022. ↩︎

- Feministki własnym głosem o sobie [Feminists in their own voice], ed. by Sławomira Walczewska (Kraków: eFKa, 2005). ↩︎

- I learned about this exhibition from Zuzanna Wilska, who is researching it. ↩︎

- Matynia, Women After Communism, 351. See also Agnieszka Graff, ‘Patriarchat po Seksmisji’ [Patriarchat after sexmission], Gazeta Wyborcza, 19 June 1999. ↩︎

- Ewa Toniak, ‘Ach, te baby’ [Ah, these women], Obserwator, 58 (1992). This and other texts on the exhibition come from the archival materials gathered by the National Museum in Warsaw. Wycinki prasowe Artystki polskie 9 September 1991-10 November 1991. Folder reference: 355. ↩︎

- Morawińska remembers participating in one of the conferences organized by eFKa, a feminist foundation created in the spring of 1991. It was dominated by such issues as abortion or domestic violence. Conversation with Agnieszka Morawińska, 13 July 2022. ↩︎

- (BZ), ‘Sztuka i sztuka kobiet’ [Art or art of women], Trybuna, 21-22 September 1991. ↩︎

- Pawel Bravo, ‘Sztuka nie ma płci’ [Art has no gender], Polityka 39 (1991). ↩︎

- Monika Małkowska, ‘Nie feminizm’ [Not feminism], Życie Warszawy, 21-22 September 1991. ↩︎

- Joanna Sosnowska, ‘Czytając katalog’ [Reading the catalog], Exlibris. Supplement to Życie Warszawy, 17 July 1992. ↩︎

- Email correspondence with Ewa Toniak and Joanna Sosnowska, 10 May 2024. Toniak mentioned that when Polish Women Artists opened, she was undertaking a fellowship in Paris, which enabled her to access some texts. ↩︎

- Artystki polskie, p. 375. This claim cannot be substantiated because it does not fit the facts; see www.wystawykobiet.amu.edu.pl ↩︎

- Anna Artwińska, Agnieszka Mrozik, ‘Generational and Gender Memory of Communism in Central and Eastern Europe. Methodological Perspectives and Political Challenges’, in Gender, Generations, and Communism in Central and Eastern Europe and Beyond, ed. by Anna Artwińska and Agnieszka Mrozik (New York: Routledge, 2021), p. 20. ↩︎

- Joanna Sosnowska, “Na marginesie wystawy Artystki polskie” [On the margins of the exhibition: Polish Women Artists], Twórczość, 9 (1992), p. 126. ↩︎

- The second was ‘to promote the scientific, scholarly, and artistic contributions of Polish-Americans.’ About – The American Institute of Polish Culture Inc. (ampolinstitute.com) [accessed 12 May 2024] ↩︎

- Blanka Rosenstiel, in Voices of Freedom. Polish Women Artists, ex. cat. (Washington: The National Museum of Women in the Arts [NMWA], 1991), p. 9. ↩︎

- Oral history interview with Wilhelmina Holladay, 17 August-23 September 2005 | Archives of American Art, Smithsonian Institution | Archives of American Art, Smithsonian Institution (si.edu) [accessed 12 May 2024] ↩︎

- They also organized solo exhibitions, for instance, the first American retrospective show of Camille Claudel (1988); Wilhelmina Cole Holladay, A Museum of Their Own: National Museum of Women in the Arts. New York (Abbeville Press 2008), 121. Holladay presents a photo depicting her and her husband next to the Greek ambassador and his wife, noting that they helped bring the Greek exhibition to the NMWA. ↩︎

- Information about the organization of the exhibition comes from the archives of the NMWA. RG 8 Curatorial. SG 1 Exhibition files. 8.1.1 Exhibition files: Voices of Freedom: Polish Women Artists and the Avant-Garde, 1880-1990. Box 5, folder 6; RG 1 Wilhelmina Cole Holladay Collection. Series 6 Exhibition project files. Subseries 1 Exhibition files: Voices of Freedom: Polish Women Artists. 19 December 1991-22 March 1992. Notes, Correspondence. ↩︎

- Letter to Agnieszka Morawińska from the NMWA, 1 February 1989. NMWA. RG 8 Curatorial. SG 1 Exhibition files. 8.1.1 Exhibition files: Voices of Freedom: Polish Women Artists and the Avant-Garde, 1880-1990. Box 5, folder 6. ↩︎

- This was with the cooperation of Aleksander Gieysztor, director of the Royal Castle in Warsaw, and at the invitation of the Polish National Committee of the International Council of Museums. ↩︎

- NMWA. RG 1 Wilhelmina Cole Holladay Collection. Series 3. Trips/engagement files. Poland, 24 September 24-1 October 1989. ↩︎

- Letter from Agnieszka Morawińska to Willhelmina C. Holladay, 20 October 1989. NMWA. RG 1 Wilhelmina Cole Holladay Collection. Series 3. Trips/engagement files. Poland, 24 September 24-1 October 1989. ↩︎

- Exhibition participation agreement and Letter to Agnieszka Morawińska from the NMWA, 8 June 1990. NMWA: RG 8 Curatorial. SG 1 Exhibition files. 8.1.1 Exhibition Files Voices of Freedom: Polish Women Artists and the Avant-Garde, 1880-1990. Box 5, folder 6. ↩︎

- Letter to Agnieszka Morawińska from the NMWA, 22 January 1991. NMWA: RG 8 Curatorial. SG 1 Exhibition files. 8.1.1 Exhibition Files Voices of Freedom: Polish Women Artists and the Avant-Garde, 1880-1990. Box 5, folder 6. ↩︎

- Kazimierz Dziewanowski, in Voices of Freedom. Polish Women Artists, ex. cat. (Washington, DC: NMWA, 1991), p. 8. ↩︎

- Ibid. ↩︎

- Voices of Freedom exhibition wall text. NMWA. RG 8 Curatorial. SG 1 Exhibition files. 8.1.1 Exhibition files: Voices of Freedom: Polish Women Artists and the Avant-Garde, 1880-1990. Box 5, folder 6. ↩︎

- For reviews of the exhibition, see the NMWA in the Arts archive. RG 13 Public relations/communications/marketing. Series 2 Exhibition press clippings. Voices of Freedom: Polish Women Artists and the Avant-Garde, 19 December 1991-22 March 1992. ↩︎

- Hank Burchard, ‘Poland’s Women Artist-Warriors’, The Washington Post, 27 December 1991. ↩︎

- Megan Hamilton, ‘Sophistication Not Isolation: Surprises from Poland’, Women’s Art Magazine 42 (1992). ↩︎

- The fact that Agnieszka Morawińska, during the preparations for both exhibitions, left the National Museum to become a deputy at the Ministry of Culture appeared to confirm this. ↩︎

Agata Jakubowska

Agata Jakubowska is a modern and contemporary art historian and a professor at the University of Warsaw. She is the author and editor of numerous publications dedicated to women artists, e.g. Feminist Art Historiography in Eastern Europe and Latin America (ed. with Andrea Giunta, “Ikonotheka” 33, 2023), Sztuka i emancypacja kobiet w socjalistycznej Polsce. Przypadek Marii Pinińskiej-Bereś (2022), and All-Women Art Spaces in Europe in the long 1970s (ed. with Katy Deepwell, 2018).