Tytuł

I never saw any socialism Interview with Dan Perjovschi

https://doi.org/10.48285/ASPWAW.29564158.MCE.2024.10.15

https://miejsce.asp.waw.pl/i-never-saw-any-socialism/

DOI

In October 2024, I curated the small exhibition Andrei Pandele & Dan Perjovschi: Witnessing pre/post Revolution in Romania in Stockholm, which brought the works of the two artists into dialogue with each other. The evening before the opening, I sat down with Dan to talk about his career.

Tell me about your professional and academic background. What motivated you to pursue an art career?

It wasn’t much of a question for me. I was good at drawing since I was a child, so after attending the local primary and high school of art, I went to the university in Iasi to study painting. I could have gone to Bucharest or Cluj but I wanted to go to Iasi because my brother was already studying music there. He was a link for me to talk to some of the students there and prepare to pass the strict exam (we had no money to pay for the teachers). By the time I started university, there was a shortage of everything in Romania, including art books. That lack of things increased corruption, and you had to have good connections to buy goods, including art books.

In those days, my colleagues and I spent a lot of time talking about art. Now it feels very funny and weird to me that we spent days thinking and talking about art, but we never did any conceptual, underground or resistance art at university. The focus was on the technical element of art, not the conceptual one. I was very critical of my studies in Iasi, but we didn’t ask any critical questions about art. Maybe a bit when we discussed art history or in connection with aesthetics, but it felt very superficial, nothing too deep. I worked harder in my last year to make the most of my time at university. But to answer your question, I really didn’t have a clear ambition to study art and become an artist. I only had these kinds of questions after I graduated from university.

What did you do after you graduated?

Well, this was communism in Romania. Anyone who went to university got an obligatory job after they graduated. It was a nationalised process: after you graduated, you sat in a teleconference call with everyone who had studied your subject and depending on your grades, the person with the highest grades was allowed to pick the first job on the list, the second-best could pick the second job, and so on. You had to do that job for at least three years.

Was the job related to your studies?

More or less. When I graduated, we were seven people in my class and for the first time, it was not a national process anymore. Each university in Iasi, Bucharest and Cluj had its own lists of jobs for their graduate students. From the seven positions offered in my year, there was only one job connected to the arts, and it was the job I took. It was a job in a museum in the western part of Romania. Most people tried to get a job close to the city where they were from, but I wanted to go as far away as possible. So, I took this job in Oradea (at the border with Hungary). My friend took a factory job. They didn’t really need him. Another colleague was responsible for folk dance, despite graduating in painting…

Did you want to stay in Oradea?

Yes. I remember to this day when I appeared in the office of the director of the museum that I was sent to, holding the paper that stated I was assigned a job in the art section of the museum. The director was rather surprised and asked who sent me there. Later, my wife Lia arrived in Oradea too (and after a year or two she found a job at the local theatre, where she painted the stage design). For me, working in the art section of the museum was like paradise. This was in 1985. Nobody was really working. The saying went like this: we are faking work, they (the Communists) are faking paying us. They called it ‘the big industry of Ceauşescu’: industries were producing things that nobody needed. We were a very paranoid country in those years. When I arrived at the museum, there was nothing to do for me. First, they asked me to do some kind of inventory of an ex-libris collection but a few days later, I was carrying large paintings and tableaux to install an art exhibition there. They used me as a non-qualified worker.

What was the museum called?

It was the Ţării Crişurilor Museum, a multi-section museum with different departments: the history section, the art section, the ethnography section, and the natural science section.

For some context, could you provide some insights into the historical and political background of Romania’s (post-)communist history?

The pyramidal communist system wasn’t working. It was a dictatorship; one man decided everything. Nothing was working anymore. The system became a caricature of the idea that everyone had a job related to their studies, but in the end, there were no specialised jobs available, and you had to take whatever job they offered you. Not working was punished. Everything was controlled, but there were some gaps. For example, they were more interested in surveilling and controlling big gatherings and crowds and therefore kept an eye on sports, theatres and the like. An exhibition opening with twenty people wasn’t of interest to them, so they let us do our exhibitions, but there were three rounds of censorship for every show and for everything printed. You had to dance with the wolves.

Every town in Romania had a theatre, a gallery, and a cultural house. Every art form had one single obligatory Union. At some point, Ceauşescu became so paranoid that he decided there were too many artists, and he stopped membership applications for the Union of Artists. He also closed a lot of high schools of art; on paper, I graduated from a pedagogic high school, not an art one. The system was cracking. If you weren’t a member of the Union of Artists, you could not access the spaces for exhibitions (the only ones that existed), get art materials (from specialised shops) or do art residencies (only national residencies, as international ones were forbidden).

Were you a member of the Union of Artists?

No, I was part of Studio 35 Oradea. Some guys in the Union were clever and created a “waiting room” for young artists under the age of 35. Member or not, you could use your status as a Studio 35 artist to access art spaces, art materials, and other stuff. When I arrived in Oradea, the local Studio 35 already existed. There were a lot of people in the group, including ethnic Hungarian artists who were much better informed than us Romanians, probably because they received information from Austria via Hungary, whereas Romania was more isolated. In any case, it was a very active group with some very good artists. As I was a museum professional, I was very active and became the driving force of the group. I was entrusted with the task of dealing with censorship. Every work was evaluated from an artistic point of view (by senior members of the Union of Artists), for its cultural value (by the cultural committee of the city) and from an ideological standpoint (by the Communist Party). They were stupid, mean and egocentric men. The whole process was a caricature designed to humiliate you rather than to truly censor the art. Crucially, Romania had different layers of art: official art and unofficial art.

Was that distinction between official and unofficial art common knowledge?

It was somewhere in between: some knowledge and information about the art world was open, other things weren’t official, and you found them out by talking to people. Oradea was somewhat special because it had one exhibition per year that focused on photography as a medium for artists. Lia (the only student) was accepted into that exhibition. I have some friends from those years who are now successful artists. They didn’t show all their art back then, only carefully selected bits. They probably didn’t want to be copied by others or to pop up on the censorship radar. I showed everything, I was like an open book. Others did some performance art and photographed it, but I only saw those photos after the revolution. The communist system imposed a strict hierarchy in the arts: at the top was the president of the Union, followed by members of the Board, the favourite artists of the Communist officials, and at the bottom were the rest of us. There was a national hierarchy of artists and a local hierarchy. If you were on top of these hierarchies, you could make a living from your art. Artists were commissioned by the Communist Party to create work for the social and cultural benefit of the town or city where they lived. You could aim for those commissions and produce this kind of public art, but you had to obey and, in some cases, kiss the ass of the Dictator or his local clones.

Were art materials and gallery spaces easily accessible during the communist period?

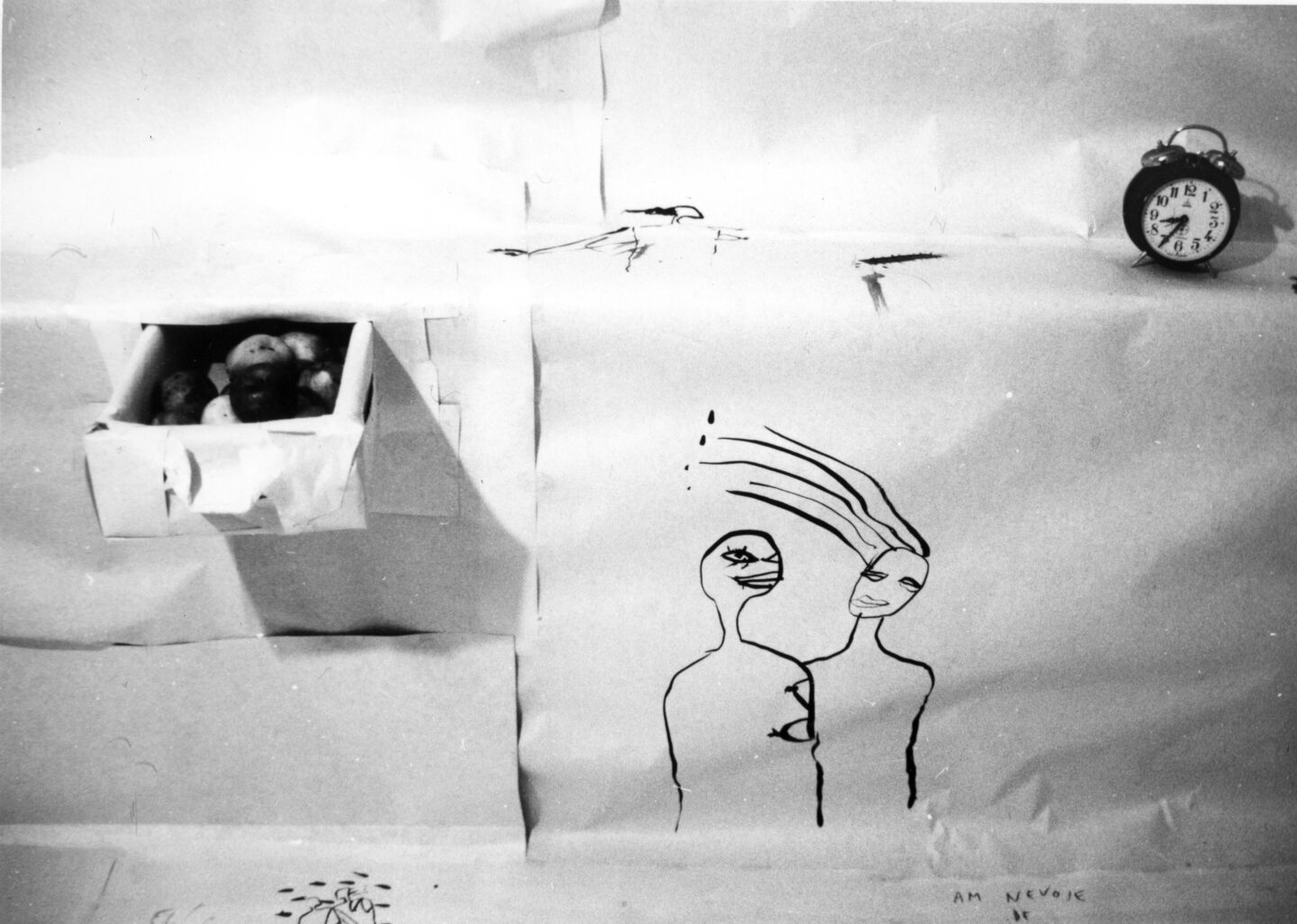

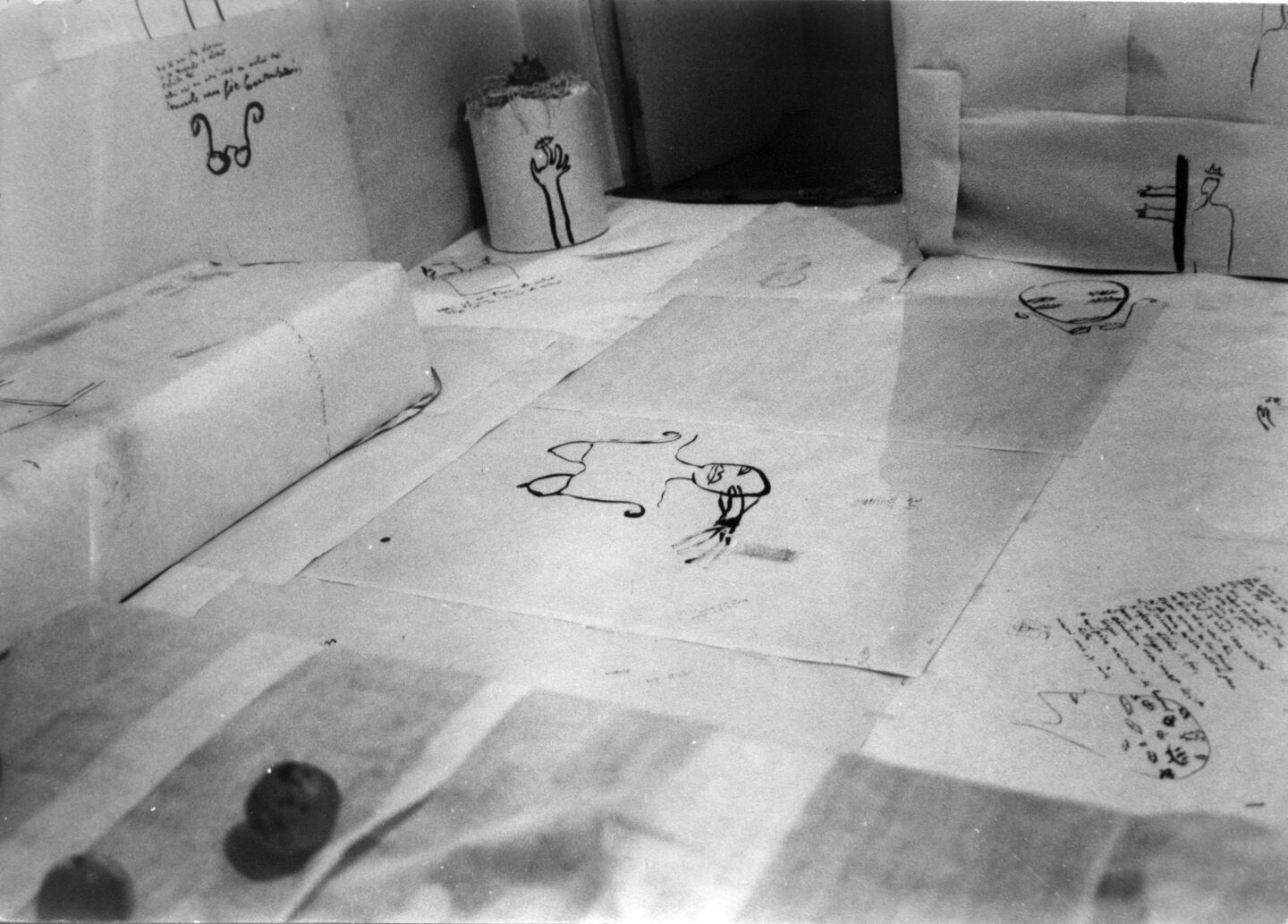

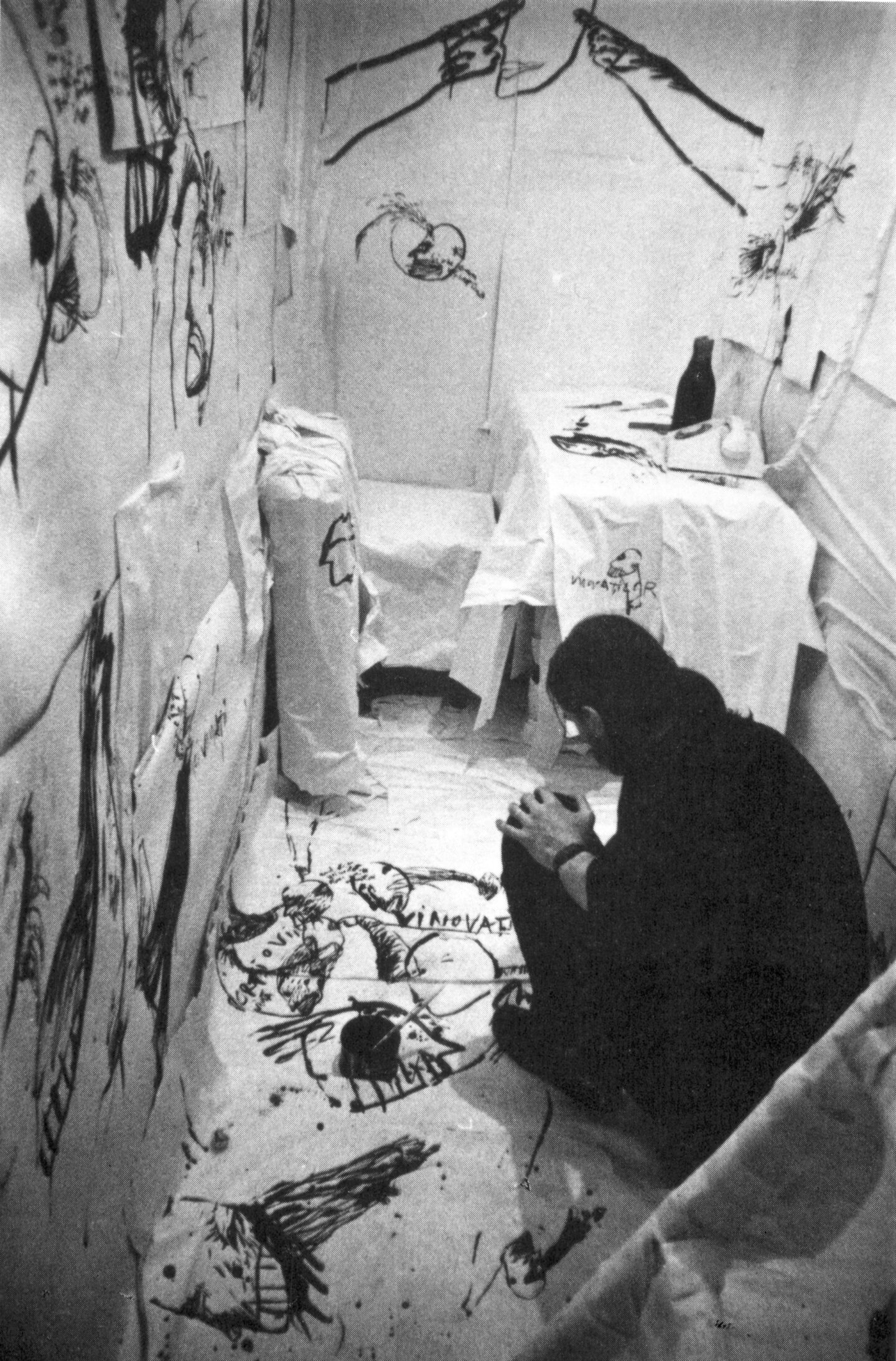

In the last decade of communism, it was difficult to find art materials. The Union of Artists had some shops that sold art supplies, but they often ran out of materials, and you had to wait until they received more stock. Foreign stuff was rare and mostly secret. If you had sources (for example, relatives living abroad), you guarded your supply and kept it for yourself, as there was a shortage of everything. When I studied in Iasi, there was no canvas available, and we painted on the back of drawers that we stole from the school furniture. Those who had money could obtain better quality art materials from abroad, but for the majority of artists, it was a constant struggle with the shortage of supplies, and they had to create work based on the materials that were available to them. If white paint was unavailable, we used toothpaste! In a way, that shaped us as artists. When I worked in Oradea, I knew people who worked in factories, and I asked them to give me some paper, plastic, or anything flat that was available and on which I could draw. So yeah, you created your artwork depending on the materials you had. Those years were the years I learned to work with nothing. That was the start of my actual practice, which is simple, adaptable, done on a low budget and with no fuss…

How did you stay motivated to do art when there was such a shortage of materials?

Uschi, it was not the lack of art materials that made you abandon art, but the censorship, the frozen present, the lack of a future, no freedom, no expression…Oradea was on the border with Hungary, so there was a little black market for everything, including art supplies. I’m part of the generation of artists who really experienced the shortage. Many specialised studios for lithography or graphic art closed because they had no supplies and no equipment to run them. In other words, I never caught the era in which art supplies were available, like the previous generation of artists did. They produced good works because they caught the little opening and the relaxation of censorship between 1966-1972. That was the most liberal period of the dictatorship; they could travel to the West, receive information, and obtain some supplies.

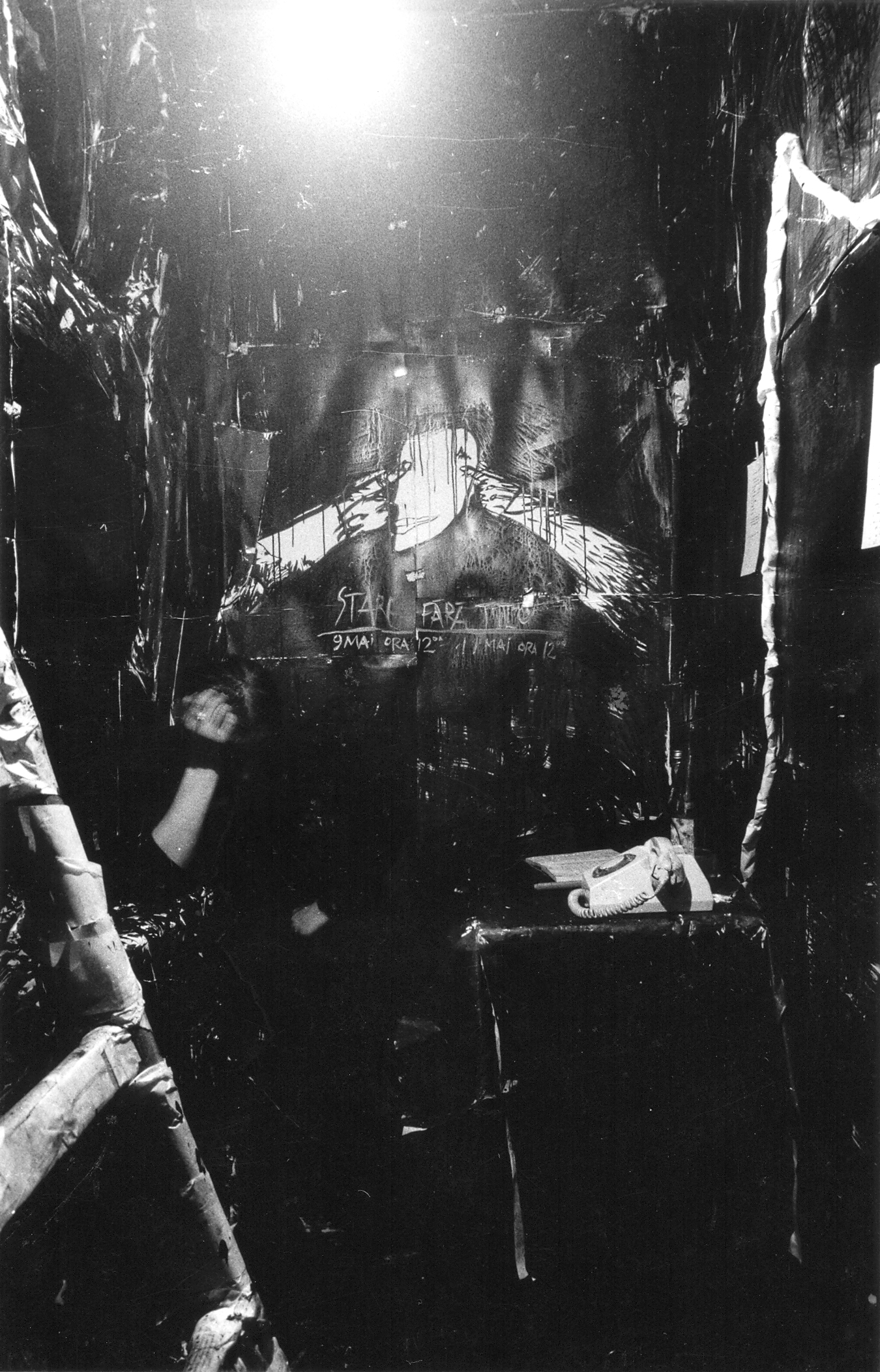

That is why the Studio 35 group in Oradea was so important. We were very active and had some kind of “revolutionary” techniques using photography or performance. We were also the first group to create a show that travelled to Bucharest, Cluj, and other places in Romania. The show was impressive and that’s why I got the job at the Ministry of Culture afterwards. Acting [performance art – UK] and exhibitions were a form of resistance, and Uschi, we never did or showed what the Communist Party asked us to do (i.e., representing “The Golden Age”, “The Beautiful &Best Society in the World” etc. That was all bullshit).

How did your working process change individually and institutionally after 1989, especially during Romania’s rough transition period of the 1990s?

Funny enough, without knowing that communism would be over, some of us were somewhat prepared. We did a lot of experimental art before the revolution. In fact, I did my first drawing on the wall in 1988. We tried to do things differently from what we saw in traditional art. At that point, we didn’t have much information from the West, so we were experimenting blindly with different ideas and media. I used photography or performance art (we called it „actions”) and the combination of the two… acting was not done for an audience but for the photo camera. I had mixed feelings about this period. On the one hand, I thought for a long time that we were some kind of cowards, who didn’t directly fight the dictatorship. On the other hand, I know now that the simple act of acting, exhibiting, meeting, and talking (while the entire society was obsessively surveilled and recorded) was the resistance. I still think I should have done more. That’s why I do what I do now… before it’s too late.

After the revolution, I was active in promoting my generation of young artists and stopping the stupid shows and exhibitions that Romania was sending abroad. A major institutional change for me was that I started working for the Ministry of Culture in 1990 (I resigned a couple of years later). The funny thing was that I did not see a conflict of interests in working for the Ministry during the day and going to protests against the government in the evening! The „new” so-called democratic regime used the working class (the miners from the Southern region of Romania) as a paramilitary force. They were brought on trains to Bucharest to crush student protests (similar to the protest in Tiananmen Square in 1989), occupy the city, and beat people to death. Anybody looking progressive, Western, with long hair and blue jeans could be attacked. I barely escaped… I was trapped in my country, marked like cattle. The human body was radical; people died on the streets for freedom. And it was cheap. We were very, very poor.

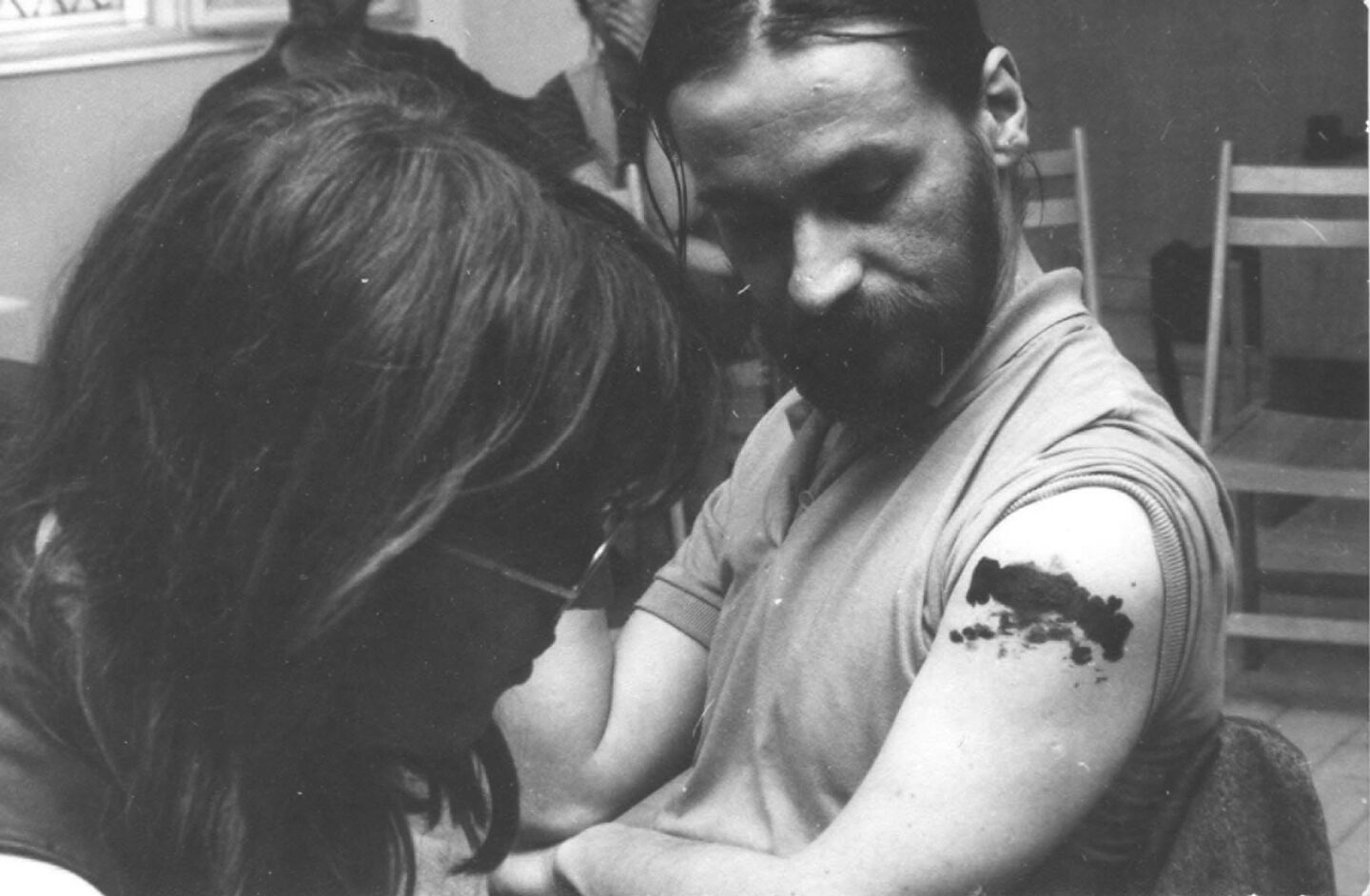

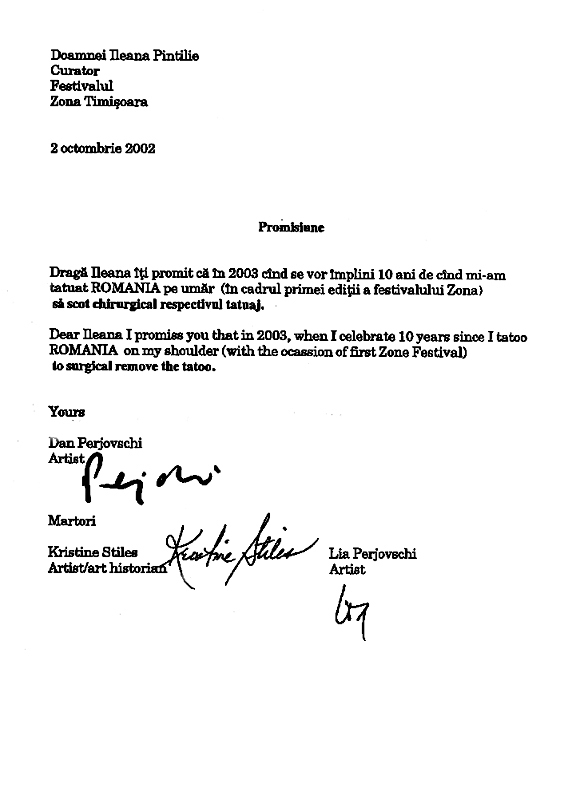

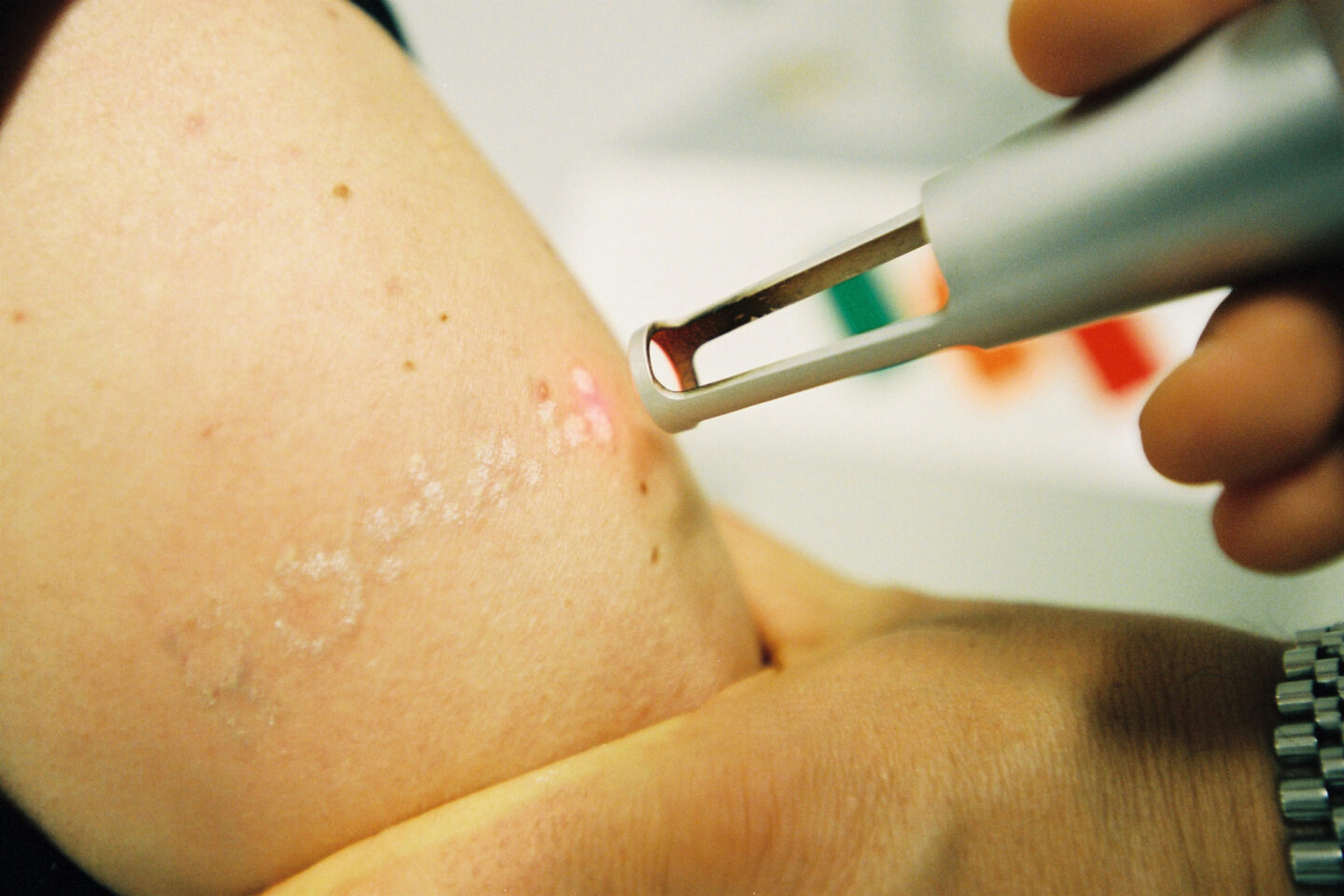

The change started after the revolution in Timisoara. In 1991, artists there initiated a three-day festival combining all the arts that the communists had forbidden, namely performance art and installation. In 1993, Ileana Pintilie started a performance festival called Zona Festival. This was the first attempt at a regional, Eastern European festival (artists from Hungary, Serbia, and Poland were invited). That year I did a tattoo piece, one of the most radical works in my career. I tattooed the name of my country on my shoulder.

Back then, there were no tattoo salons for the wider population in Romania, only sailors and criminals had tattoos. That was also the time when we started discussing questions like What is art? What is performance? There were also several other performance festivals popping up around Ana Lake in the mountains of Transylvania, or the Periferic Festival in Iasi (near the eastern border of Romania) in 1997. Periferic later became the International Biennial of Contemporary Art. It started as a fringe festival but grew increasingly bigger. It stopped after several editions because the organisers got exhausted. The big event now is Art Encounters, a good medium-sized biennial of art in Timisoara.

In the first decade after the huge political change, we were more naïve in Romania compared to other countries and artists, but that gave us the power to experiment with our ideas. We were part of this very progressive period of exhibitions and festivals. We also found ourselves in opposition to neo-orthodox artists. Suddenly, these guys were praying to Jesus… whatever religious activity the communists prohibited, these people suddenly picked that up again. At the beginning, they even accused us of being anti-Romania because our progressive art and performance pieces were different, more radical compared to the conservative work they produced.

In 1994, I got a scholarship in the US through the USIA & Mid-America Arts Alliance. I was taken around different states in the US and visited artist-run and alternative art spaces. That really opened my world. In 1995, I got the ArtsLink fellowship and a residency and project at Franklin Furnace in Tribeca, New York City. To maximise the six-week residency, I arranged with Martha Wilson, who is a well-known performance artist in the US, to start on day one and draw with a pencil on the walls of the gallery. I made a grid and drew a portrait in each square. That took me a month. The opening was on 1 December, on World AIDS Day, so we gave everyone who attended the opening an eraser and invited visitors to erase one portrait or more in the memory of friends who died. It was great, I felt powerful, because I controlled the space. Many people attended the opening, and the exhibition was featured in the magazine Art in America. That same year, I published the book Postcards from America, while the Contemporary Museum in Chicago organised an exhibition with East European artists. I was one of them, and they put my work on the cover of the catalogue. It was a big body of work entitled Athropoteque, the Library of Humans, with stacks of drawings, actually 5,000 of them, designed in a way that one could touch and flip through the work… It took me three years to complete that. Later, I sold it to the famous collector Peter Ludwig, the guy who opened the Ludwig Museums in Cologne, Aachen, and Budapest. This also showed me that things were happening.

This development was a slow process. First, we [Dan and Lia – UK] wanted to learn about Western art that we had never heard of before, then we tried to participate and be part of it, and after that, we aimed to distribute the knowledge we had acquired locally in Romania. We promoted, supported, and actively participated in the progressive local art scene. Lia developed a project titled The Archive of Contemporary Art, later the Center for Art Analysis. Lia went from Body Art to studying the Body of Art and I went from working on paper to working on the walls of art museums and galleries. For us, art is not art but a way of life… We came from the revolution. To this day, we both are still active outside traditional art territories.

You mentioned your first wall drawing was in 1988. When did you start directly drawing on the walls of galleries and museums?

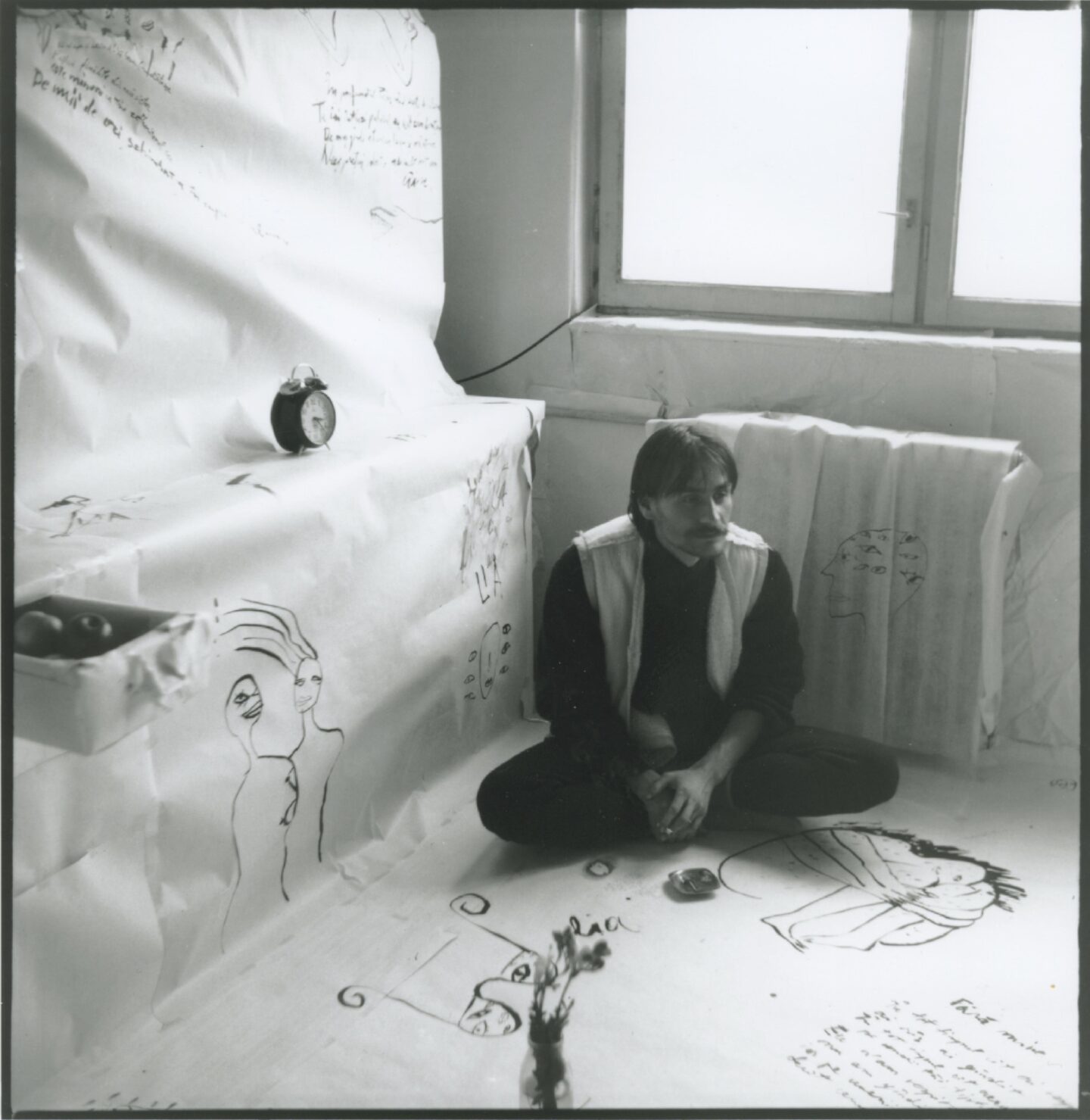

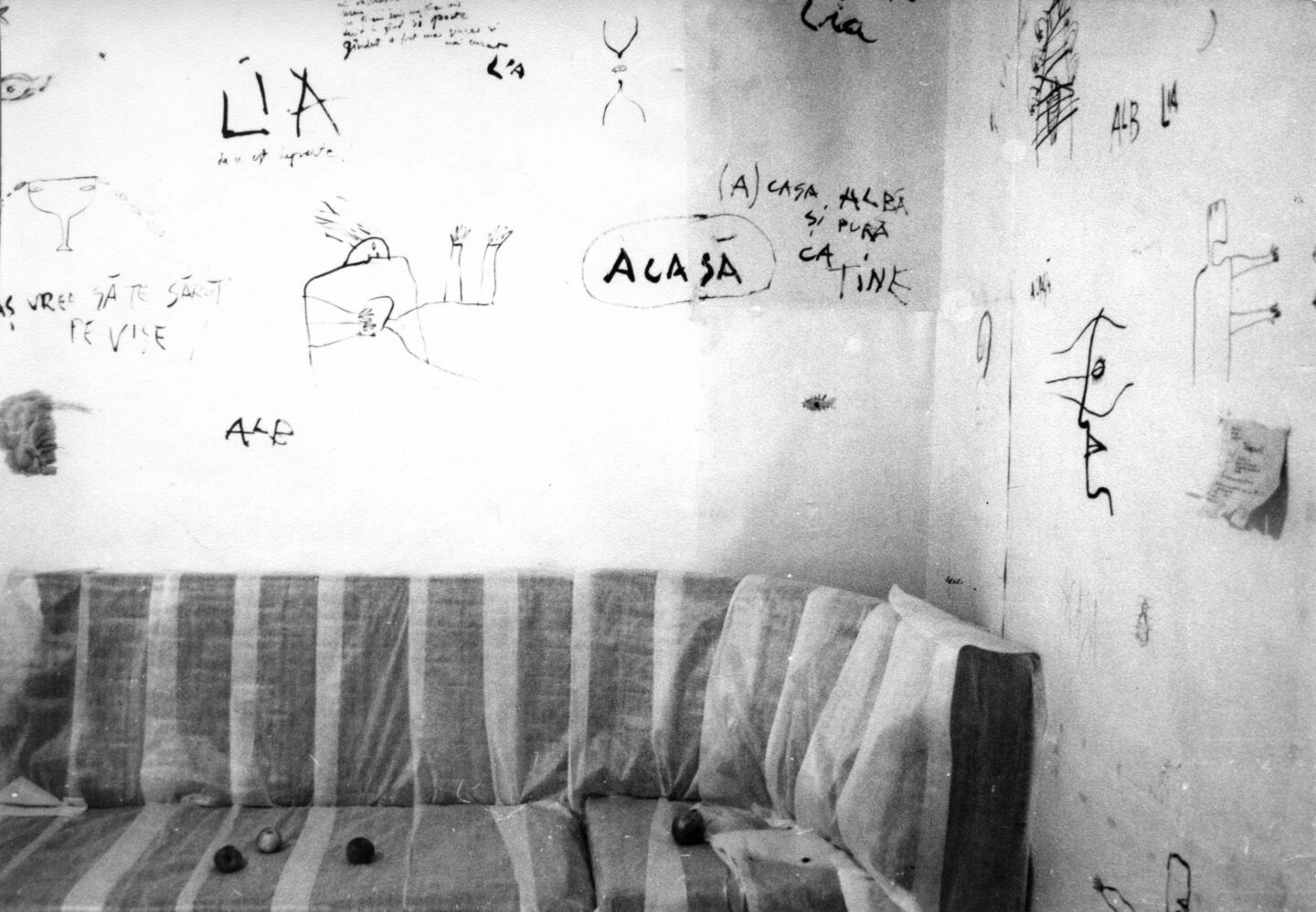

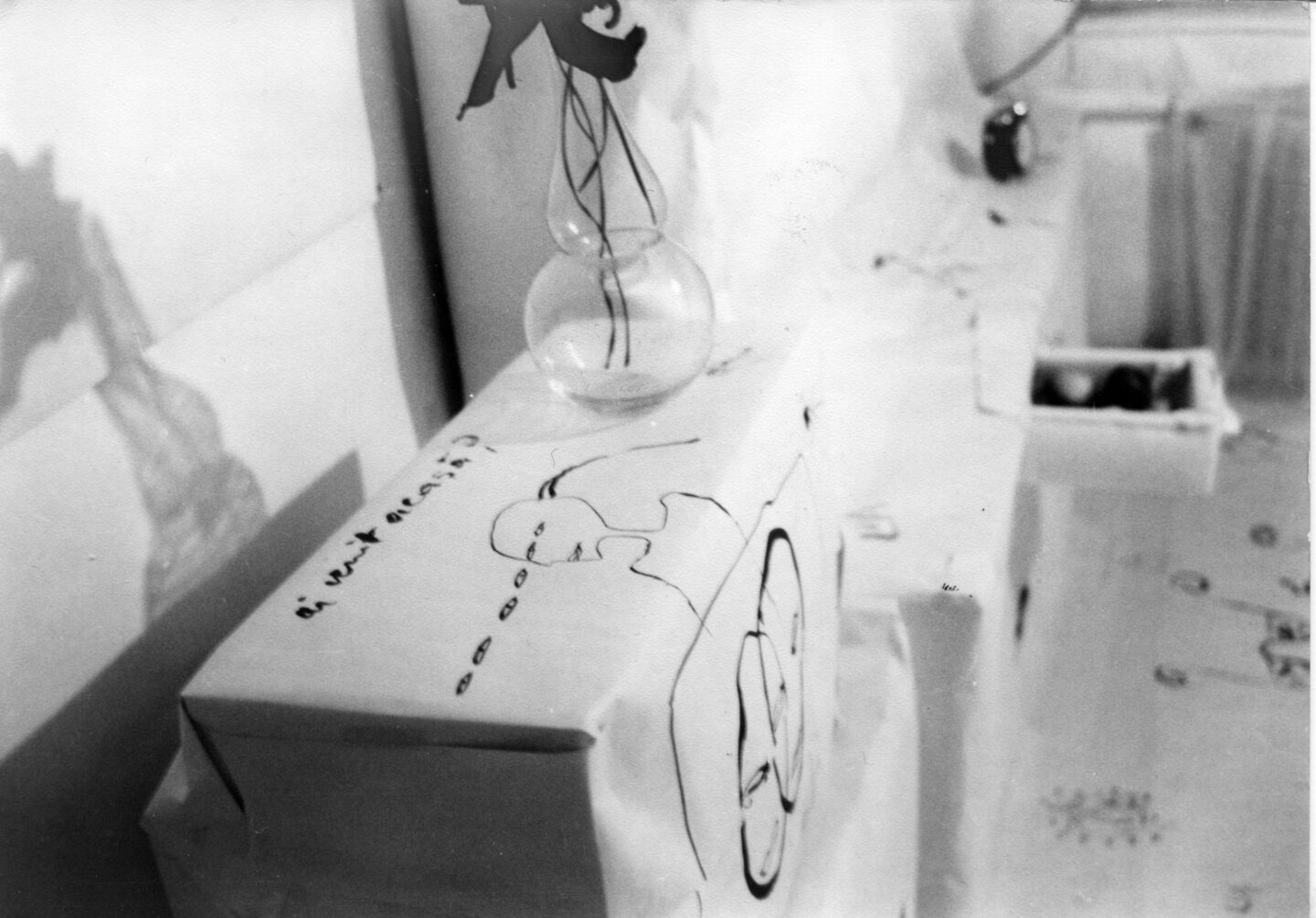

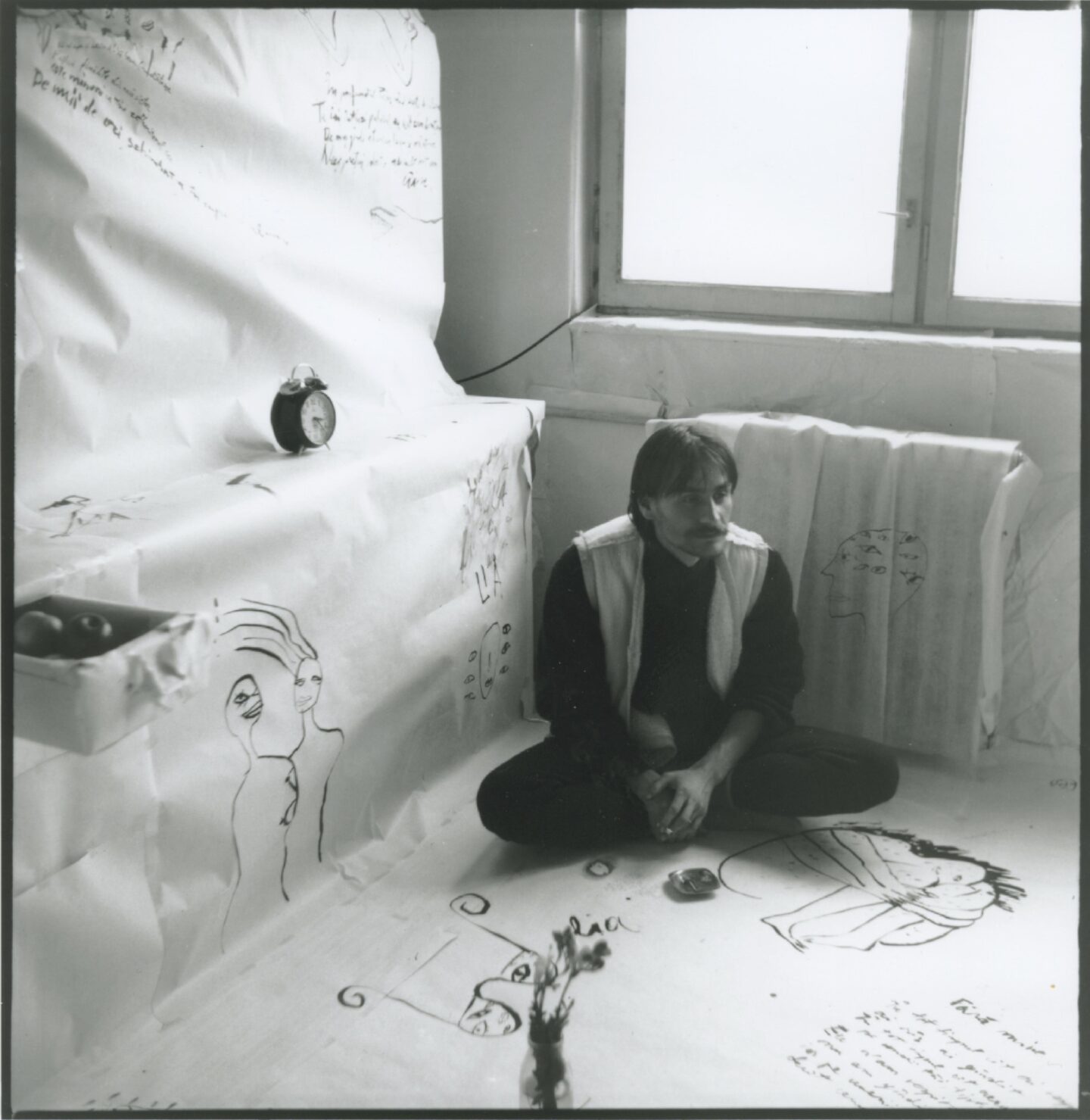

In 1988, I wrapped my flat (everything, including the couch, TV and furniture) in white paper and drew on it. It was a surprise for Lia for her first student holiday.

Initially, I drew more on the floor but then I transitioned to the walls for the exhibition in Ibid, London, but the drawings there were still thin and delicate little stories. When I was offered big rooms or rooms with dark rough walls, very brutal, I couldn’t draw thin lines of tiny stories anymore and instead had to use charcoal, which is how my drawings became bigger over time.

You had solo exhibitions in Athens, Rome, Basel, London, New York City, several cities in Germany, as well as several group shows at Biennales in Venice, Sydney, Sao Paolo and Istanbul. When did you make the leap to an international career, was it a particular body of work?

The process was gradual until the late 1990s, and in 1999 came the breakthrough. For the first time, there was an open contest for the Romanian Pavilion at the Venice Biennale. I told the curator that I would like to go and draw on the floor. That became a very successful piece, entitled rEST. The public had to literally step on the drawings. The first important invitation I received after that was in 2003. I was invited by a very prominent curatorial duo, Marius Babias, who is now running the Neuer Berliner Kunstverein in Berlin, and Florian Waldvogel. They did a radical project for three years at Kokertei Zollverein Essen, in the Ruhr area of Germany, called The Open City: Models for Use.

Each year, they did a very critical show with a semi-permanent installation. I was invited to participate in the second year and represented graffiti by drawing on walls. Kaspar König, a famous German curator and at the time director of the Ludwig Museum in Köln, attended the opening in 2003 and liked my work very much, so he invited me to do a big show in Germany in 2005. Somebody at Tate Modern saw it, and in 2006 I did a project supported by Tate members. Somebody at MoMA saw it… and the rest is history. While working with big museums and biennials, I always tried to do little things in artist-run spaces with little or no budget. I started with those guys, which I will never forget.

By the sounds of it, your experience in the US gave you the recognition and exposure as an international artist from Romania.

Yes, and in the 1990s I also started to publish my cartoons and drawings in magazines, first in Contrapunct, this was the magazine of the young writers, and then in Revista 22, which was the magazine for the intellectuals. That gave me exposure outside the art world. When I say „magazine”, do not expect anything glossy. Revista 22 is printed in black and white on newspaper paper. It’s low quality paper and not fancy, but I’ve always loved that.

Art Historian Octavian Eşanu created a new epistemic framework that shaped the perception of art in post-communist countries. He coined the term „post-socialist contemporary”, by which he refers to new norms regarding the meaning/topics of art and its aesthetics, Westernisation, open society, liberalism, etc., in post-communist countries. Do you agree with his theory?

I don’t know his theory and am not sure what he is referring to. But I got tired of the self-colonisation and Westernisation of my society. We are and have been part of the so-called West. The Romanian language is mainly Latin, I grew up in a part of Romania [Transylvania – UK] that belonged to the Austro-Hungarian Empire, my city has the German name Hermannstadt, and the school I attended was based on a French model. We have been occupied and colonised by the Soviets, by Russia.

Post-socialist contemporary? Hmmm… Well maybe, but I never saw any socialism. Just a pyramidal society with one man at the top deciding everything. Is North Korea a socialist country? If yes, then Romania was too. I grew up in a totalitarian regime and had to adapt. My father’s part of the family escaped to Romania (because of the Red Army) from a part of the world now known as Ukraine… I am a son of a refugee.

I really disagree with this view of the West „occupying” the East. What is the problem with the Soros Foundation or the Open Society concept? I love it. A place where everybody has a place. Because of the Communist dictatorship, there were no civil rights groups in Romania, no civil society at all. The Soros Foundation helped us to recover, build a network of social and cultural activists, and connected us to a world network so we aren’t alone. The fact the actual tyrants and the extreme right hate Soros is a sign he did well.

The model of the Kunstverein in Germany, Austria, and Switzerland is the best model you can have for an art institution, because it’s based on membership for anybody, not just for artists. The money comes from the members’ fees, and then it’s further financed by the city, the county and finally at the national level. These are four levels of financing. We didn’t have that in communism, because only artists were allowed to become members of the Union of Artists. In Germany, anyone can become a member of the Kunstverein. Why do we still think that communism was good with that kind of exclusivism and control? Uschi, I love Western contemporary art history, theory and practice… It’s critical. The communists forbade us from knowing about it or being part of it. They interrupted our history. We had to work enormously to recover, learn, and understand it. And now, it is no longer Western Art but Global Art. We expand our knowledge with the rest of the world. Beautiful. We integrate decolonisation and the critique of the hegemony of ONE art history. Isn’t that great? Do not colonise me with „your” decolonisation thinking… Let me have a say. Let me tell you my experience of living and fighting totalitarianism. You may need it now…

How did you navigate the experience of „post-socialist contemporary” (neoliberal market pressure, aesthetics,”‘open society’,” Westernisation, etc.) as an artist after 1989?

First, we need to understand what is meant by neoliberal market pressure. In my country (Romania), we were told that the moment we could travel freely outside the country, everything would be bad and a mess. It would be bad for artists to sell their work in the art market. But how are artists supposed to live? Should we ask the working class/taxpayers to pay them? Why shouldn’t artists sell their own work? The exaggeration of art markets is problematic, but the idea that you can sell your art and make a living from it – what’s the problem with that? And in terms of market pressure, what market pressure? I live in Romania; I didn’t relocate to Germany or the US, where Eşanu lives. I live in Sibiu, not even in Bucharest. Did you see any pressure on me? Or Westernisation of what? We learned in school during the communist time what was Western. I studied in Sibiu and in Iasi and learned about Cezanne etc., not about the African cultures. Even Brancusi made his career in Paris, that’s where it kicked off, not in Romania.

I’d like to ask about the nature of your drawings. Just like happenings and performances, your work is relatively ephemeral. Does that matter to you?

I don’t really care if my drawings disappear after the show. I started with drawings in newspapers, which get thrown away every day too, and it’s the same with my drawings on the walls; they disappear eventually from public view. But they stay in the notebooks where they first originated. My wall drawings have also changed over time because of the drawings I’ve done in newspapers. They used to be more complex, but I have simplified them because of the speed of reaction, the size of the space in which I draw has increased, and the time to draw has become shorter and shorter. Hence, I draw simpler and bigger statements. When one of my wall drawings is repainted in some place in the world, another drawing pops up in a different part of the same world… Uschi, I never stop.

Until 1997/98, I used a grid system that filled the entire wall, and I filled every square with a little human portrait. It took me ages… Now I’m working freestyle and quick-style. I draw stories, I am a reporter using walls as newspaper pages. I still illustrate book covers and newspapers, so I keep a foot outside the art world. When I have an opening in Romania, people from different sectors attend, which is very cool.

Do you keep your notebooks with all the drawings?

Most of them, I have hundreds. I do one or two for every project, and I work on 15-25 projects per year. Since 2010, I no longer put them on the art market and only offer the notebook(s) to the public museums that invite me. They have the opportunity to keep my work permanently. Several museums have bought them, actually 20. But there is also the potential to do my drawings again. I can re-use a drawing and combine it with a new drawing to re-contextualise the old one. My drawings are constantly developing depending on where I exhibit and what’s going on at the time. In a way, my drawings are not so ephemeral.

How important is it for you (and your work) to create an impact on your audiences?

Well, it works well, my drawings have an impact on people the minute they walk into the gallery and see my drawings on the wall. Google me or look me up on Insta and you’ll see the impact!

What kind of feedback do you receive on your work from different parts of the world? Do audiences respond differently and if so, how?

Generally, I receive very positive feedback about my work. I am invited to draw on walls all over the world. All the time. At any given moment, there are several wall drawings of mine on view somewhere on the planet. Quite often, curators ask if they can keep my work longer (after the show ends), which I see as positive feedback too. But there are times when curators don’t get my drawings, and they ask me to explain them. When I was in Seoul, they asked me to explain three drawings because they didn’t „get” the Western’ humour. However, I’ve never had a really negative reaction to my drawings. When people see me during the process of drawing on the walls, they like my drawings more and approach me about my work. I often become friendly with the security guards when I’m in a space for several days, and they start asking me about my work too. That’s nice. I use a lot of cultural and political references, and not everyone gets them, but I also try to learn something new from the places I visit and incorporate that in my work.

Dan, thank you very much for your time and interesting insights into your artistic practice and career.

Uschi Klein

Dr Uschi Klein is an early career researcher and lecturer at the University of Brighton, UK. Her current research focuses on photography as a form of cultural resistance in communist Romania (1947–1989), as well as on decolonising the Western photography canon to broaden knowledge by including marginalised and under-represented perspectives. Her recent publications include a chapter in the volume The Camera as Actor (Routledge 2020) and articles in academic journals, including Visual Studies and Visual Communication.