Tytuł

From State-Controlled to Neoliberal Art Trade The Case of the Artéria Galéria (Artery Gallery) in Hungary

https://doi.org/10.48285/ASPWAW.29564158.MCE.2024.10.9

Art trade, state socialism, 1980s, transition period, postsocialist contemporary art

https://miejsce.asp.waw.pl/from-state-controlled-to-neoliberal-art-trade/

Abstrakt

This paper examines the activity of one of the first artist-initiated commercial galleries in state-socialist Hungary that was independent of the state-controlled institutional system: the Artery Gallery (1986–2008), an initiative of twenty-two artists in the town of Szentendre. The case study explores the circumstances under which a collective of local artists, who were critical of the political system, was granted a gallery space by the municipality at the town centre amid the decentralization process of the art infrastructural system in the 1980s. The Artery Gallery was not a typical commercial gallery in the sense that it was operated by a loose artists’ collective, incorporating a wide range of artists and styles, including representatives of geometric abstract and neo-avant-garde art, surrealism, dadaism, happening and experimental music, among others. Their primary aim was to create a self-sustainable model for trading local and underrepresented contemporary art, and they sought to maintain founding values such as the autonomy of art production – as opposed to politically approved art – and openness to the combination of local artistic traditions and contemporary trends. While the gallery aspired to act both as a commercial unit and a representative art venue within the city’s cultural life, the conflict between artistic and economic considerations increasingly undermined its activities, which demonstrates the transformation of the framework of art production due to the liberalization of its institutional system prior to 1989. By reconstructing the history of the Artery Gallery as well as its predecessor, the Szentendrei Grafikai Műhelyés Galéria (Szentendre Graphics Workshop and Gallery, 1980) based on publications, archival material, and interviews with former members and managers, the paper aims at a better understanding of how such initiatives navigated the changing economic and political climate of late socialism.

Słowa kluczowe

Art trade, state socialism, 1980s, transition period, postsocialist contemporary art

DOI

Introduction

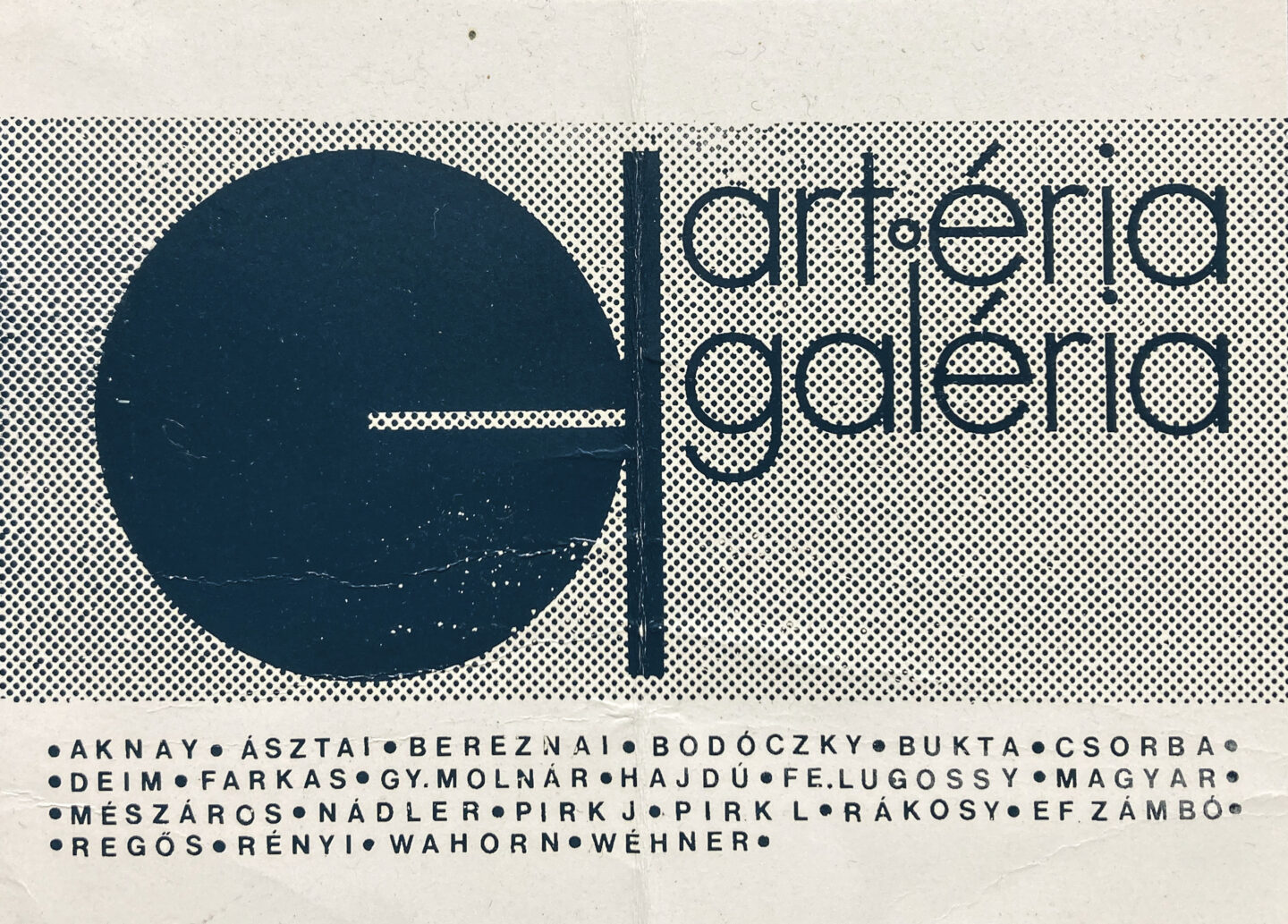

Amid the neoliberal modernization of cultural production unfolding in the 1980s, the permission to operate commercial galleries was part of the decentralization process of the totalitarian institutional system, facilitating sales opportunities independent from the Képcsarnok Vállalat (Gallery Company), the official body that controlled the art market under state socialism1. One of the early instances of independent, artist-initiated galleries was the Artery Gallery (Artéria Galéria), founded in 1986 by twenty-two artists in Szentendre, a town known for its vibrant art scene about twenty kilometres north of Budapest.2 The Artery Gallery was not a typical commercial gallery in the sense that it was an art space operated by a creative community (alkotóközösség) – an organizational form that enabled artists to break away from the Gallery Company’s former monopoly, as I will discuss below – that incorporated a wide range of artists and styles, including representatives of geometric abstraction and neo-avant-garde art (Imre Bak, Pál Deim, Ilona Keserü, István Nádler), surrealism, dadaism, happening and experimental music, represented by members of the Vajda Lajos Stúdió (for example, Imre Bukta, László feLugossy, István ef Zámbó, András Wahorn), among others.

Many of the gallery’s members did not enjoy the support of state institutional system, but as the political leadership withdrew from firm censorship in the early 1980s, the option to operate a gallery provided them with sales and exhibition opportunities at a time when the neoliberal art trade was undeveloped in the country. Their primary aim was to create a self-sustainable model of trading local and underrepresented contemporary art, and they sought to maintain the founding values, such as the autonomy of artistic production – as opposed to politically approved art – and openness to the combination of local artistic traditions and contemporary trends.3 Although the members were representatives of various generations and artistic tendencies, the common goals created a degree of cohesion between them at the beginning. Such community-oriented endeavours were characteristic of the unsupported art scene of the Kádár era (for instance, Hejettes Szomlyazók, Inconnu, Indigo, Vajda Lajos Stúdió, Xertox), and most of these groups dissolved around the political transition of 1989, whether or not due to financial reasons.4

The Artery Gallery aspired to act both as a commercial unit and a representative art venue within the city’s cultural life, and the conflict between artistic and economic considerations increasingly undermined its activities. The discrepancy between the aesthetic and monetary value of art was one of the central themes of artistic debates throughout the changing politico-economic reality of the 1980s, as the principles of the neoliberal approach to artistic production gained more ground. For instance, a long debate took place in several journals and newspapers already in 1980–1981 about the question of whether culture is a commodity.5 The focus of the art scene gradually shifted from the local to the international, market-oriented art world, and there was increasing awareness of Western artistic discourses, too, partly due to the coverage of Western art events in the only art magazine at the time, Művészet, which also addressed questions related to the neoliberal transformation of the Hungarian art trade.6 In light of such changes in the institutional and conceptual framework, artists needed to adopt a more competitive approach rather than purely artistic programs, which quickly eroded the community-oriented mindset that had characterized the endeavours of the Artery Gallery’s founders in the mid-1980s.

Scholarship tends to agree that it was not the political transition of 1989 that brought radical changes in the Hungarian art institutional system – or in terms of art trends – because the liberalization of the socialist model of art production had already been underway since the early 1980s.7 József Mélyi called the period between 1980 and 1983 the ”regime change” of the art institutional system because a series of legislative reforms facilitated the modernization of the infrastructure of art, and new leaders with a progressive approach were appointed at top art institutions (for instance: Katalin Néray at Műcsarnok/Kunsthalle Budapest, Lóránd Bereczky at the Hungarian National Gallery), who remained in position throughout the political transition and beyond.8 Mélyi also highlighted that the program of “new sensibility” formulated by Lóránd Hegyi in his 1983 book9 aspired to embed Hungarian contemporary art in a predominantly Western context: “Hegyi, who repeatedly formulated his program not only in books but also in the form of exhibitions, wanted to demonstrate the appearance of a new creative attitude in Hungary – and not a new style – one that could be matched with international contemporary tendencies.”10 Such ambitions of art historians and museum directors who strove for the international embedding of Hungarian art brought new perspectives into the local artistic discourse prior to the political transition of 1989.

As far as the growing influence of the neoliberal art trade is concerned, Lajos Németh concisely summarized the challenges he observed in the late 1980s as follows:

The difficulty lies in the fact that the autonomous art sphere cannot be formed overnight. It’s not a matter of determination. The monopoly of the art trade has ended – which was a pseudo-art trade, as we have seen – but, albeit uncertainly, private enterprises are beginning to be established, and the descendants of the former creative communities are the most viable. But there is still a lot of uncertainty, especially regarding art trade abroad. We lack professionals, managers and expert-type art historians. (…) And the Hungarian market does not have enough capital to sustain a truly lively art scene.11

In sync with Németh’s observation, László Beke underlined that as the market-oriented approach gained ground already in the 1980s, the most significant challenge for the art scene was the increasing pressure of competition due to the uncontrollable art market and lack of knowledge and experience in this regard, which had far-reaching consequences for artists’ collectives and individual trajectories.12

The founding members of the Artery Gallery had to navigate the transforming political and economic environment of the 1980s, after being socialized within the state-controlled institutional system throughout a large part of their careers during the 1960s–1970s, when the cultural politics of the Kádár regime (1956–1989) were consolidated under the supervision of György Aczél.13 The institutional system that took full control over art production in Hungary had already evolved by 1964, and included the Ministry of Culture, Magyar Képzőművészek és Iparművészek Szövetsége (Association of Hungarian Artists and Craftsmen, 1949), Képzőművészeti Alap (Fine Arts Fund, 1952, thereafter Arts Fund), as well as Képző- és Iparművészeti Lekotorátus (Lectorate of Fine and Applied Arts, 1963), the administrative authority responsible for censorship and the authorization of exhibitions and public artworks.14 This model remained in place until 1989; however, the authority of the state apparatus weakened due to the decentralization of the institutional system, which was largely an outcome of the economic crisis in the late 1970s and consequent economic reforms.15 For instance, a legislation in 1982 deprived the Lectorate of some of its authority and loosened the system of control regarding exhibitions.16

Another legislative reform in 1982 enabled the commercial activity of creative communities (alkotóközösség),17 which had come under the control of the Arts Fund in 1955 and had been deprived of their selling rights.18 Two years after the legislation, there were over twenty active creative communities, but most of them could not operate a gallery.19 Among the first instances of artist-initiated commercial galleries were the short-lived Rabinec Studio (1982–1983), a gallery housed in a private home, founded by artists Ákos Birkás, Zsigmond Károlyi, Károly Kelemen, Lóránt Méhes, János Vető, and art historian Zsuzsa Simon;20 and the Artery Gallery, the history of which I will elaborate below.

Art trade was controlled by the Gallery Company, founded in 1948 – after the communist takeover of the country and the nationalization of private art dealing organizations – as an institution that was supposed to replace the art market. In 1952, the Gallery Company merged into the Arts Fund – a body that largely controlled art production until the regime change of 1989, providing artists with commissions, scholarships, pensions, and studios.21 As part of the Arts Fund, the Gallery Company was responsible for art commerce and related exhibitions throughout the country, as well as acquisitions on a weekly basis, supervised by a committee to ensure that both political-ideological prerequisites and social considerations (i.e. to provide a livelihood for artists) were met. It maintained several showrooms in Budapest, including Csók István Gallery, Csontváry Hall, Derkovits Hall, Dürer Hall, Mednyánszky Hall, Paál László Hall, and other galleries (so-called “shops”) in the county centres. Since the Gallery Company bought and offered for sale a large number of artworks based on the politically committed jury’s choices, its collection failed to meet the actual demand and quality standards.22

As the Kádár regime gradually opened up towards the West during the 1980s, foreign organizations were allowed to operate in Hungary, and a hybrid art trading infrastructure incorporating both socialist and capitalist mechanisms evolved. The liberalization of the art institutional system was necessary due to the economic difficulties; for instance, the Arts Fund was unable to pay allowances for artists after 1986, so the privatization of its subsidiaries began in 1987.23 The first Western gallery, operated by the Vienna-based Hans Knoll, opened in 1989; the Ludwig Foundation was formed in 1987, and the Ludwig Museum opened in Budapest in 1989. Commercial galleries began to appear in the mid-1980s, including ones operated by state institutions, such as the Qualitas Gallery (1985), established by the Arts Fund to sell artworks to foreign buyers at considerably higher prices than those of the Gallery Company.24

Alongside these, the Soros Foundation opened the Fine Arts Documentation Centre in Kunsthalle Budapest in 1985, which aimed to support counter-cultural or “avant-garde spirited” art (as opposed to state-approved art), and compiled information about artists, scholars, and art dealers. In 1991, the foundation expanded its activities as the network of Soros Centres for Contemporary Arts (SCCAs) in seventeen other Central and Eastern European countries, organizing exhibitions, projects, and providing grants to artists and initiatives. The SSCAs played a vital role in creating new entanglements of Western and Eastern European contemporary art networks and strengthened the cohesion between the art scenes of the region, based on an essentially Western take on contemporary art, making the network a powerful agent of the Westernization of contemporary art in Hungary.

According to Octavian Esanu’s conceptualization of the “postsocialist contemporary” or “Sorosart,” the Soros network constructed a specific understanding of contemporary art in the Central and Eastern European region, which was easily integrated into the Western discourse but was limited to interpreting the art of the formerly socialist region within Western trends.25 He argued that in the new paradigm represented by the infrastructure of “Sorosart,” the focus shifted away from artistic programs and the dichotomy of autonomous versus socialist art toward the realm of art management, and the role of curators, archivists and art traders became more prominent in determining the notion of contemporary art.

In connection with this observation, Sven Spieker pointed out in a conversation about Esanu’s book that the palette of artistic trends and practices during the transition period was far more diverse than what the somewhat deductive category of “Sorosart” suggests because contemporary art did exist in the former Eastern Bloc long before the regime changes, even though it was not labelled as “contemporary art” but rather as unofficial, dissident, underground or ordinary art, moreover, the region’s art scenes did have contacts with Western countries before 1989, which factors were underrepresented in Esanu’s work.26 Spieker’s remark underlines that a major shift in the approach towards art stems from the different frameworks of art production in state socialism and in the free market economy, with far-reaching consequences for art trade – including the activity of the Artery Gallery.

As far as the relationship between the Artery Gallery and the Soros Documentation Centre is concerned, the latter documented the activity of some of the gallery members, and its board members maintained good relationships with several artists belonging to the gallery,27 but there was no substantial connection between the two institutions.28 The history of the Artery Gallery underscores that the art scene of Hungary was far more complex than what the notion of the “postsocialist contemporary” allows one to assume, and that artistic practices were deeply embedded in local cultural and historical contexts, which, in this case, had a greater influence on the local art production than Western discourses on contemporary art.

Szentendre Graphics Workshop and Gallery: Artery Gallery’s Predecessor

The local institutional system of the town of Szentendre emerged largely in the “Aczél era,” the period dominated by György Aczél’s cultural policy in the 1960s–1970s.29 While it had been a touristic town with an art colony (Régi Művésztelep/Old Art Colony, 1926)30 and a museum, the Ferenczy Károly Museum (1951), a series of institutional developments made Szentendre into a significant center of modern and contemporary art at the time. The town became the county center of the Pest Megyei Múzeumok Igazgatósága (Directorate of Pest County Museums) in 1962, headquartered in the Ferenczy Károly Museum, which was expanded and reopened as the Ferenczy Museum in 1973. In 1969, a brand-new art colony was completed, incorporating twelve studio apartments (Új Művésztelep/New Art Colony, 1969).31 The existing Old Art Colony’s twelve studios were renovated in 1972, and the complex received an exhibition venue. Additionally, a new cultural center opened in 1975 (Pest Megyei Művelődési Központés Könyvtár/Pest County Cultural Center and Library), and the municipality received valuable artist estates, such as that of Margit Kovács due to György Aczél’s decision (1972), and others, mostly via donation: the estates of Béla Czóbel (1975), Jenő Barcsay (1977), János Kmetty (1981), Imre Ámos and Margit Anna (1984), and Lajos Vajda (1986), all of which later became part of the Ferenczy Museum’s collection.32 Furthermore, an exhibition venue opened in the historic town center in 1978 (Szentendrei Képtár/Szentendre Gallery), which belongs to the Ferenczy Museum Center today.

Such developments largely enriched the cultural life of the town, attracting more and more artists to settle down there in these years. For example, young artists – most of whom arrived from various parts of the country – established the Vajda Lajos Stúdió in 1972, and the group received a workshop space from the municipality in 1973 (6 Péter Pál Street). The members of the non-conformist Vajda Lajos Stúdio – most of whom did not complete formal art education – were representatives of mostly experimental forms of art, including performance art, happening, music, film, and also painting.33 Not surprisingly, the state institutional system did not support the group but its artists became members of the Szentendre Graphics Workshop and Gallery and the Artery Gallery, and many of them became canonized artists after 1989.

Seeing the possibilities and the state’s favourable approach toward Szentendre, artists began to actively shape their environment initiating art spaces, such as the Szentendre Graphics Workshop and Gallery, and the Artery Gallery. The main organizers of both initiatives were painter Pál Deim (1932–2016) and sculptor Ádám Farkas (b. 1947), and with the support of other artists and art professionals, they mobilized the local community of artists to gain more independence from the state-controlled art infrastructure. Both initiatives aimed at creating space for local artists to display and sell their works in alternative ways, but they did so in significantly distinct ways. The two galleries were structurally different and represented different approaches to art trade, reflecting the changes within the art institutional system during the 1980s, which gradually embraced the prospects of a free market economy.

The idea of the Szentendre Graphics Workshop and Gallery emerged in the 1970s, when the silkscreen technique enjoyed growing popularity in Hungary. It was largely inspired by the Budapesti Műhely or Pesti Műhely (Budapest Workshop), a silkscreen workshop in Benczúrutca, Budapest, which was founded in 1973 based on Imre Bak, János Fajó and István Nádler’s 1971 program (further members included András Mengyán, Tamás Hencze and Ilona Keserü).34 This group was closely connected to the Józsefvárosi Galéria (Józsefváros Gallery, 1976), led by János Fajó, a venue that played an important role in the representation of neo-avant-garde art. Although the artists connected to these initiatives were not supported by the state apparatus per se, the political leadership tolerated the activities of the Budapest Workshop and the Józsefváros Gallery. They contributed not only to the popularization of the silkscreen technique but also to the dissemination of knowledge about artists outside the canon of the state socialist system.35 The members of the Budapest Workshop invited Pál Deim to create serigraphs – he was Imre Bak and István Nádler’s former fellow student at the Academy of Fine Arts and member of the same intellectual circle, Zugló Circle (1958–1968)36 – who was accompanied by Ádám Farkas.37 Inspired by the Budapest Workshop’s activities, the two artists decided to establish a graphics workshop and a gallery in Szentendre,38 and they developed the idea along with the Szentendre-based Imre Kocsis, professor at the University of Fine Arts in 1968–2008, who had expertise in the silkscreen technique.39

Once the idea crystallized, the artists agreed to form an official body to represent their interests in the municipality following Ádám Farkas’s suggestion, who then initiated the Pest County unit of the Association of Hungarian Artists and Craftsmen (Magyar Képzőművészek és Iparművészek Szövetsége Pest Megyei Területi Szervezete).40 Farkas explained the importance of acting collectively as follows: “We soon realized that if we act as a community to represent various art-related issues, then the controlling power that had swept us off the table more than once would eventually take note of our existence.”41 After they proposed the idea of the workshop at the Pest County Municipality on behalf of the new unit of the Association, emphasizing the large number of prominent artists living in the town, the Szentendre Graphics Workshop and Gallery was approved, and the silkscreen workshop began to function in January 1980 with thirty-six members.42 They were granted a space in the town centre (20 Marx Square, today’s 20 Main Square)43 and a full-time professional printmaker to aid the artists (Mihály Lipták). The members could work there for a week each year, and they occasionally invited other artists too. According to the workshop’s 1989 and 1991 exhibition catalogues, György Kepes and Tamás Konok were among their guests.44 Every member produced a limited number of thirty prints and fifteen EA prints (including obligatory copies for the Ferenczy Museum, the municipality and the Pest Megyei Műtárgybank / Pest County Bank of Artifacts).45

The graphics workshop’s leadership included eight members: six board members, an artistic director elected by all the members, and the secretary of the local unit of the Association (who was Ádám Farkas) – a construct that ensured their internal autonomy. The first board, between 1980–1984, comprised those who actively shaped the initiative at its early days, such as artists László Balogh, Pál Deim, László Hajdú, Imre Kocsis, Endre Lukoviczky, István Gy. Molnár, and art historian Ferenc Hann.46 The members represented various generations, including prominent elderly artists (Jenő Barcsay, Endre Bálint, Dezső Korniss, Piroska Szántó, Júlia Vajda, Erzsébet Vaszkó), mid-career representatives of post-war abstract painting (for example, József Bartl, Pál Deim, Ilona Keserü, István Nádler), sculptors (for example, Ádám Farkas, Dezső Mészáros) and members of the Vajda Lajos Stúdió, among many others.47

According to former members, the workshop was more than a technical facility because artists could meet there and exchange their thoughts, so it functioned as a community space, too. As Ilona Keserü recalled, “[Pál Deim and I] constantly ran into each other at the workshop. On the one hand, he was working on his prints, and on the other hand – as he would say with a smile – he was coming to gather some information, to meet his colleagues there. And indeed, we sat down while working to take a break and we discussed things.”48 Pál Deim also emphasized this aspect of the workshop: “Artists who otherwise did not keep in touch could also meet there.”49 In other words, beyond technical resources, the workshop provided an opportunity for the artists to maintain their professional relationships and form new networks.

Alongside the workshop, the artists proposed the establishment of a joint gallery (aka. the Workshop Gallery) already in 197950 to merchandise the serigraphs they produced, which opened in the same building as the silkscreen workshop, on September 25, 1981. As Ádám Farkas remembered, “At that time, there were no private galleries, meaning that if someone did care who they exhibited with and what they exhibited, then the so-called creative community was the only – let’s add, instinctive – escape route from the monopoly of the Gallery Company.”51 Indeed, the Szentendre Workshop and Gallery provided an alternative way for its members to produce and sell artworks, but their commercial activity was still under the control of the Gallery Company because creative communities were not granted permission to sell their own works at the time.

As far as its organizational structure is concerned, the Szentendre Graphics Workshop and Gallery was maintained by the Arts Fund and the Directorate of Pest County Museums, and further supported by the Municipality of Szentendre, the Pest County Municipality, the Pest County Cultural Centre and Library, and the Pest County unit of the Association.52 Somewhat paradoxically, the artists could manage the graphics workshop independently but the gallery was supervised by the Gallery Company. Compared to the “shops” managed by the Gallery Company, however, the Workshop Gallery enjoyed certain privileges: it focused on local fine arts (and did not include applied arts); it enjoyed exclusive selling rights for two years (works could not be sold in other units of the Gallery Company or elsewhere); it acted as a mediator, so the artists had a say in the pricing of their works (in contrast to the Gallery Company’s pricing, which first bought the works and then sold them); and they could also sell paintings, small sculptures, and plaques alongside prints.

The Gallery Company appointed László Erdész as managing director of the Workshop Gallery – who had previously managed the Gallery Company’s “shop” in the town of Dunaújváros – and, although such a compromise was acceptable for the artists, personal conflicts with the managing director arose early on. Pál Deim formulated the members’ concerns in a letter addressed to Sándor Csontos of the Gallery Company already in 1982, and the Workshop’s leadership announced its unwillingness to collaborate with Erdész on January 31, 1984.53 The Gallery Company investigated the case multiple times but did not remove Erdész from the post.54 Eventually, the increasing tension between the artists and the managing director led to a break between the members, paving the way for the establishment of the Artery Gallery.

Artery Gallery: Navigating Between Aesthetic and Market Principles

The Artery Gallery was founded in 1986 by twenty-two artists who had left the Workshop Gallery55 due to deepening conflicts with the managing director.56 Collaborating with art historians Lajos Golovich and Tibor Wehner, the founding members led by Pál Deim and Ádám Farkas established a creative community (Art’éria Képzőművészeti Alkotóközösség / Artery Fine Arts Creative Community) in accordance with the 1982 legislation, which enabled the commercial activity of such communities. This made complete independence from the Gallery Company possible, the only indication of state control being that the Arts Fund formally monitored the gallery’s artworks.57 The initiative enjoyed the support of Mayor István Szini, so the municipality granted it a gallery space for a low rent in the town center, right across the Town Hall, about a hundred meters from the Szentendre Graphics Workshop and Gallery (1 Városház Square). Pál Deim underscored the role of the mayor in this regard: “István Szini resolved the tension that had developed among the artists of Szentendre at that time, and with a building and business premises, he helped the dissenting artists to forge a creative community.”58 Szini was invited to hold the welcome speech at the opening of the gallery on the March 12, 1986, underlining the good relationship between him and the artists.

Invitation Card for the Opening of the Artery Gallery, including the Names of the Founding Members, 1986

The gallery received a favorable reception from the art scene, and the events of its first years were surrounded by general curiosity. In its initial phase, between 1986–1992, the artistic director was Tibor Wehner, an art historian and writer who had previously worked as a museologist in the town of Tata, and Johan van Dam, a freshly graduated anthropologist from the Netherlands who joined him as a sales representative in 1988–1992. The gallery attracted many collectors not only from Hungary but also from abroad, as curiosity towards the region’s art increased in the late 1980s and foreign collectors sought affordable but high-quality artworks. It organized several group and solo shows throughout the country,59 which were solely financed by the income from sales and membership fees.60 As a special economic unit, the Artery Gallery not only sold and exhibited artworks, but also offered various services based on the expertise of its members, such as the design of murals, plaques and artistic keepsakes, framing, portrait painting, book illustration and graphic design.

Despite the rather successful start, the conflict of values between the aesthetic and the economic approaches to art was apparent from the beginning of the Artery Gallery’s existence. The members were explicit about its primary mission as a cultural venue to showcase underrepresented local contemporary art, and commercial motivations were of secondary importance. Tibor Wehner formulated this principle in 1987 as follows: “disregarding the aspects of saleability – or classifying them as second-rate – these artists from the city of the Danube Bend offer for sale works born in the spirit of realizing artistic goals, and at the same time present a slice of contemporary art of Szentendre to their visitors – with a constantly changing collection and fresh works – in their gallery.”61 Although its members shared commercial interests as well as a positionality against the Gallery Company, the Artery Gallery could not formulate a clear program to position itself due to their lack of experience in the neoliberal art trade.62

Besides prioritizing artistic and cultural aspirations over profitability, the gallery had to face further challenges. The artists insisted on maintaining the principle of equal representation of all the members, disregarding the demands of buyers and collectors. This resulted in imbalances and internal conflicts, because it was basically the more successful artists whose sales covered the maintenance costs, yet some less successful ones demanded more effort from the sales representative to sell their works. In a letter to the members, Johan van Dam warned about such issues in 1990: “Once and for all, it must be decided whether the Artery Gallery is a circle of friends or a business, in a commercial sense. If this is really a business, then the rules must be strictly adapted to the market economy, which means internal competition and the survival of the fittest.”63 He argued that only about half of the members had considerable sales in the years 1988–1989, especially those who sold works for non-Hungarian collectors, such as Peter and Irene Ludwig, and Roland Riz (János Aknay, István Bodóczky, Imre Bukta, Pál Deim, László Hajdú, László feLugossy, István Nádler, András Wahorn, István ef Zámbó). To illustrate his point, Van Dam highlighted that the revenue solely from István Nádler’s works made up 38.8% of the annual income of the gallery in 1989. He suggested that profitable artists be represented more emphatically, and he urged the admission of new members whose works were in demand. Notably, Imre Bak and Ilona Keserü joined the gallery in 1990 (the latter remained a member only until 1992).

After the political transition of 1989, the challenges posed by the neoliberal market economy worsened the conflict between the gallery’s founding principles and the individual interests of the artists. As competition between newly established private galleries tightened after 1989, several artists left the Artery Gallery and joined other galleries in Budapest – for instance, Imre Bukta, István Nádler and István Regős moved to the Várfok Gallery (established in 1990) – and non-local members became increasingly inactive (for example, Imre Bak, László feLugossy, Viktor Lois, András Wahorn). Another problem the gallery struggled with was that collectors preferred to make deals directly with the artists to avoid paying commission to the gallery. Negotiations between the artists and the gallery managers were also difficult because the managers were basically employees of the creative community – which became a cultural association (Art’éria Galéria Kulturális Egyesület/Artery Gallery Cultural Association, 1993, Artéria Kulturális Egyesület/Artery Cultural Association, 2000)64 – so their suggestions were subject to the artists’ preferences. Additionally, there was a time of crisis in the management, as several managers and sales representatives – most of whom had no experience in the art trade – came and went in the period between 1992–1995 due to various reasons, involving the lack of positioning and profiling of the gallery at a time when such improvements were increasingly important to succeed in the art market.

To overcome the difficulties, the members invited an entrepreneur, László Horváth, who managed a successful picture framing and art trading business in the town of Nagycenk, named Horváth & Lukács Gallery. He took over the Artery Gallery’s management between 1995–1998 with a clearly market-oriented approach: “I’m not ashamed, I’m a trader. I want to not only present these works, but primarily to sell them” – he declared in an interview.65 He invested in the renovation of the space, which reopened on May 18, 1995, and employed a sales representative, but eventually quit in 1998 because the gallery was not profitable.66

Following this period, Johan van Dam returned to manage the gallery between 1998–2006, and organized several solo shows for the members as well as a group exhibition celebrating the twentieth anniversary of the gallery’s foundation.67 Eszter Bohus, the last gallery manager in 2006–2008, began to compile a publication about the first twenty years of the gallery, but it remained unpublished.68 While the management took the requirements of the emerging art market into consideration after 1995, it became increasingly challenging for the Artery Gallery to compete with other galleries during the late 1990s and 2000s, especially the ones in the capital. Furthermore, artists needed to focus on their individual careers in the new socio-economic reality of post-socialism, so the former community of the Artery Gallery, organized around shared goals, gradually dissolved by 2008.

Conclusion

The history of the two artist-initiated institutions I described above demonstrates some key aspects of the transition from a state-controlled to a neoliberal art trade in Hungary. Due to the transformation and liberalization of the art institutional system prior to 1989, neo-avant-garde and non-conformist artists could find ways to operate art spaces and galleries with state approval during the 1980s. The organizational structure of the two galleries in question demonstrates this process. While the Szentendre Graphics Workshop and Gallery could only exist as part of the state institutional system in 1980, it enjoyed privileges compared to the galleries of the Gallery Company. Founded only a few years after that, the Artery Gallery could operate independently as a creative community, and became one of the first instances of commercial galleries in late socialism.

In line with the increasingly market-oriented dynamics of art, conflicting aesthetic and market principles undermined the operations of the Artery Gallery, which had to adapt to the imperative of profitability over artistic programs and cultural pursuits. Thus, the initial focus on community and the autonomy of art production gradually shifted towards a managerial approach that prioritized profitability, especially as the competition between artists and institutions increased significantly after 1989. The history of the Artery Gallery and its predecessor, the Szentendre Graphics Workshop and Gallery, underlines the entanglements of institutional changes with local histories not only regarding the dynamics of art trade but also the conceptualization of contemporary art within the new framework produced by the neoliberal and democratic transformation.

Bibliography

Andrási, Gábor. “A Zuglói Kör (1958–1968). Egy művészcsoport a 60-as évekből” [The Zugló Circle (1958–1968). An Artist Group from the 1960s]. Ars Hungarica, 1991 (1).

Andrási, Gábor. Zuglói Kör [Zugló Circle] (catalogue, introductory essay). Budapest: No. 5 Galéria, 1993.

Andrási, Gábor. “Motívumrejtő absztrakció a Zuglói Körben 1961–1968” [Motif-Concealing Abstraction in the Zugló Circle 1961–1968]. Ars Hungarica, 1998 (1).

Ars Hungarica, 2011/3. „A hosszú hatvanas évek” [The long 1960s]. https://epa.oszk.hu/01600/01615/00086/pdf/.

Barkóczi, Flóra. “Creative (Dis)Courses. The Forms, Methods and Locations of Alternative Art Pedagogy in Hungary.” In Art in Hungary 1956-1980. Doublespeak and Beyond, ed. Edit Sasvári, Hedvig Turai and Sándor Hornyik. Thames and Hudson, 2018: 95–113.

Beke, László. “Rendszerváltozás – művészeti változások” [Change of the System – Changes in Art], Budapesti Negyed 14, 1996 (4). Epa.oszk.hu, https://epa.oszk.hu/00000/00003/00012/index.htm.

Bodonyi, Emőke and Gábor Pataki. Veszélye csillagzat alatt – Az Európai Iskola (1945–1948) [Under a Dangerous Constellation – The European School (1945–1948)]. Ferenczy Museum Center, 2024.

Bohus, Eszter (ed.). Akció és reakció. Szentendre és az Artéria művészei 1986–2006. [Action and Reaction. Szentendre and the Artists of Artéria 1986–2006] (manuscript in Pál Deim’s archive, courtesy of Johan van Dam), 2008.

Borus, Judit (ed.). Keretek Között. A hatvanas évek művészete Magyarországon, 1958–1968 [Within Frames. The Art of the Sixties in Hungary, 1958-1968]. Hungarian National Gallery, 2017.

Chikán, Bálint. “Régi-új Artéria” [Old-New Artery Gallery]. Szentendre és vidéke, 15 June 1995.

Cseh-Varga, Katalin. “Turning Private into Public. Apartment Culture.” In Katalin Cseh-Varga, The Hungarian Avant-Garde and Socialism. The Art of the Second Public Sphere. Bloomsbury Publishing, 2022.

Deim, Pál. “Isten veled, Artéria Galéria!” [Farewell, Artery Gallery!] In A nagy művészet csendben növekszik – válogatott művészeti írások [Great Art Grows in Silence – Selected Writings on Art], ed. Tibor Wehner. Napkútkiadó, 2016 [2008].

Deim, Réka. “Amit nem lehet kiszerkeszteni – Beszélgetés Bak Imrével” [What cannot be Engineered. Interview with Imre Bak]. ArtPortal, 2020. Accessible via UvA DARE: https://pure.uva.nl/ws/files/60357805/_Amit_nem_lehet_kiszerkeszteni_Besz_lget_s_Bak_Imr_vel_artportal.hu.pdf.

Deim, Réka. “Farkas Ádám emlékei – Deim Pál: Csendek” [Ádám Farkas Remembers – Pál Deim: Silences] (interview). Ferenczy Museum Center, 2022. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=srYYF6d-fK8.

Deim, Réka. Interview with Ilona Keserü (video), October 30, 2023. Archive of Ferenczy Museum Center.

Dudás, Barbara. “Életműkiállítások. Emlékmúzeumok születése és halála” [Oeuvre Exhibitions. The Birth and Death of Artists’ Memorial Museums]. The Flowers of Transition – The Art of Hungary in the 1980s. Conference organized by the Research Department of the Central European Research Institute for Art History (KEMKI) – Museum of Fine Arts, Budapest, May 31, 2022. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=SNnAHhUVnSk.

Esanu, Octavian. The Postsocialist Contemporary: The Institutionalization of Artistic Practice in Eastern Europe after 1989. Manchester University Press, 2021.

F., J. “Artéria: faltól falig galéria” [Artery: Gallery from Wall to Wall]. Népszabadság, 12 October 1993: 16.

Fowkes, Maja and Reuben. “Placing Bookmarks: The Institutionalisation and De-Institutionalisation of Hungarian Neo-Avant-Garde and Contemporary Art.” Tate Papers 2016 (26). https://www.tate.org.uk/research/tate-papers/26/placing-bookmarks.

Golovich, Lajos. “Navigare necesse est!” In Akció és reakció. Szentendre és az Artéria 1986–2006. [Action and Reaction. Szentendre and the Artists of Artéria 1986–2006] ed. Eszter Bohus (manuscript in Pál Deim’s archive, courtesy of Johan van Dam), 2008.

György, Péter and Gábor Pataki. Az Az Európai Iskola és az elvont művészek csoportja [The European School and the Group of Abstract Artists]. Corvina, 1990.

Hajdu, István. “Műtörténet borostyánba zárva. Zuglói Kör: 1958–1968” [Art History Enclosed in Amber. The Zugló Circle (1958–1968)]. Kritika, 1993 (5).

Hann, Ferenc. Szentendrei művészek grafikái [Graphics by Szentendre Artists] (exhibition catalogue). Ócsai Művelődési Ház, May 12-20, 1980.

Hann, Ferenc. Szentendrei Grafikai Műhely kiállítása [An Exhibition of the Szentendre Graphics Workshop] (exhibition catalogue). Pest Megyei Művelődési Központ és Könyvtár, 1989.

Hegyi, Lóránd. Új szenzibilitás [New Sensibility]. Magvető, 1983.

Hornyik, Sándor. “Budapesti Műhely” [Budapest Workshop]. In Kortárs magyar művészeti lexikon I [Lexicon of Contemporary Art in Hungary I.],ed. Fitz Péter. Enciklopédia kiadó. 1999: 341.

Horváth, György. A művészek bevonulása. A képzőművészet politikai irányításának és igazgatásának története 1945–1992. [The March of Artists. The History of the Political Leadership and Administration of Visual Arts 1945–1992]. Corvina, 2015.

Huth, Júliusz. “Képzőművészeti viták és kritikák az 1980-as években” [Artistic Debates and Criticism in the 1980s]. In Kiállítások és kritikák. Képzőművészeti diskurzusok az 1980-as években [Exhibitions and Criticism. Artistic Discourses in the 1980s], ed. Júliusz Huth and Kristóf Nagy. Central European Research Institute for Art History (KEMKI) – Museum of Fine Arts, 2025: 17-69.

Huth, Júliusz and Kristóf Nagy. Kiállítások és kritikák. Képzőművészeti diskurzusok az 1980-as években [Exhibitions and Criticism. Artistic Discourses in the 1980s], ed. Júliusz Huth and Kristóf Nagy. Central European Research Institute for Art History (KEMKI) – Museum of Fine Arts, 2025.

Kertész, László. A Képző- és Iparművészeti Lektorátus története 1963-tól 2007-ig, avagy kultúrpolitikák és egy intézmény átváltozásai [The History of the Lectorate of Fine and Applied Arts from 1963 to 2007, or Cultural Policies and the Transformations of an Institution]. Hungarian National Gallery, 2019.

Knoll, Hans (ed.). Második nyilvánosság – 20. századi magyar művészet [The Second Public Sphere – Hungarian Art of 20th Century]. Verlag der Kunst, 2002.

Kolozsváry, Marianna (ed.). Csak tiszta forrásból. Hagyomány és absztrakció Korniss Dezső művészetében [From the Clearest Springs. Tradition and Abstraction in the Art of Dezső Korniss]. Hungarian National Gallery, 2018.

Mazányi, Judit. Egytől egyig szita. A Szentendrei Grafikai Műhely 30 éves jubileumi kiállítása, 2010. július 9 - augusztus 22. [From First to Last, Silkscreen Prints. The 30 th Anniversary Exhibition of the Szentendre Graphics Workshop, July 9 - August 22, 2010]. PMMI Ferenczy Múzeum, 2010.

Mélyi, József: “Rendszerváltás, 1983. A továbbélő nyolcvanas évek” [System Change, 1983. The Lasting 1980s]. Enigma, 2019 (99): 13–21.

Menyhárt, László. “Aklotóközösségek, kisvállalkozások” [Creative Communities, Small Cooperatives]. Művészet, 1983 (10): 2–8.

Nagy, Kristóf. “A Soros Alapítvány képzőművészeti támogatásai Magyarországon” [Fine Arts Grants of the Soros Foundation in Hungary]. Fordulat Társadalomelméleti Folyóirat, 2014 (21): 192–215.

Nagy, Kristóf. “From Fringe Interest to Hegemony. The Emergence of the Soros Network in Eastern Europe.” In Globalizing East European Art Histories. Past and Present, ed. Beáta Hock and Anu Allas. Routledge, 2018.

Nagy, Kristóf. “Rabinec Studio: The Commodification of Art in Late Socialist Hungary, 1982–83.” In Contemporary Art and Capitalist Modernization. A Transregional Perspective, ed. Octavian Esanu. Routledge, 2020: 139-152.

Nagy, Kristóf. “Az eladás elég jó poszt-avantgárd eszme? A Rabinec Stúdió és a művészet áruvá válása az 1980-as években” [Is Selling a Good Enough Post-Avant-garde Idea? The Rabinec Studio and the Commodification of Art in the 1980s]. Exindex, February 21, 2024. https://exindex.hu/hu/flex/az-eladas-eleg-jo-poszt-avantgard-eszme/.

Nagy, Kristóf and Márton Szarvas. “Left Turn – Right Turn. Artistic and Political Radicalism of Late Socialism in Hungary. The Orfeo and the Inconnu Groups.” Contradictions. A Journal for Critical Thought5, no. 2 (2021): 57–85.

Németh, Lajos. “A kortárs művészet megújulásának lehetőségei. Az 1987. szeptember 27–29. között rendezett siklósi Nemzetközi Szimpózion Konferencia előadása” [Possibilities of the Renewal of Contemporary Art. Presentation at the Siklós International Symposium, September 27–29, 1987]. In Szimpózionok és alkotótelepek Társaságának periodikája. Symposion Társaság, 1990. Republished in Gesztus vagy alkotás. Válogatott írások a kortárs Magyar képzőművészetről [Gesture or Creation. Selected Writings on Hungarian Contemporary Art]. MTA Művészettörténeti Kutató Intézet, 2001: 308–318.

Novotny, Tihamér. “Színre hangolt szitanyomatok. Beszélgetés Kocsis Imrével” [Colour-tuned Silkscreen Prints. Interview with Imre Kocsis]. 10+1 éves a Szentendrei Grafikai Műhely (exhibition catalogue). Pest Megyei Múzeumok Igazgatósága, 1991.

Novotny, Tihamér (ed.). A szentendrei Vajda Lajos Stúdió: 1972–2002 [The Lajos Vajda Studio in Szentendre: 1972–2002]. Vajda Lajos Stúdió Kulturális Egyesület, 2002.

Novotny, Tihamér and Tibor Wehner (eds.). A szentendrei Vajda Lajos Stúdió: 1972–2002. Vajda Lajos Stúdió Kulturális Egyesület, 2000.

Petőcz, György and Noémi Szabó (eds.). Vajda Lajos – Világok között [Lajos Vajda – Between Worlds]. Ferenczy Museum Center, 2016.

Piotrowski, Piotr. In the Shadow of Yalta: Art and the Avant-garde in Eastern Europe, 1945–1989. Reaktion, 2009.

Rappai Zsuzsa. A Szentendrei Új Művésztelep [The New Art Colony of Szentendre]. Ferenczy Museum Center, 2019.

Sasvári, Edit, Hedvig Turai, Sándor Hornyik (eds.). Art in Hungary 1956-1980. Doublespeak and Beyond. Thames and Hudson, 2018.

Szabó, Ernő P. “Termékenyítő légkör. Kezdők fillér nélkül” [Fertilizing Atmosphere. Beginners without a Penny]. Szocialista Művészetért, 1984.

Tóth, Antal. A Szentendrei Régi Művésztelep [The Old Art Colony of Szentendre]. Corvina, 2007.

Várnagy, Tibor. “Láthatatlan történet” [Invisible Story]. Szamizdat. Alternatív kultúrák Kelet-és Közép-Európában 1956-1989 [Samizdat. Alternative Cultures in Eastern and Central Europe 1956-1989] (exhibition catalogue), Stencil Kiadó – Európai Kulturális Alapítvány, 2004. https://www.c3.hu/~ligal/111lt.html.

Wehner, Tibor. A szentendrei Artéria Galéria kiállítása [An Exhibition of the Artery Gallery, Szentendre] (exhibition catalogue). Ceglédi Galéria, November 9–29, 1987.

Wehner, Tibor. “A szentendrei Artéria Galéria” [The Artery Gallery in Szentendre] (manuscript in Pál Deim’s archive, courtesy of Tibor Wehner). 2008a

Wehner, Tibor. “Artéria Galéria dokumentáció” [Artery Gallery documentation] (manuscript in Pál Deim’s archive, courtesy of Tibor Wehner). 2008b

- I presented this research within the framework of the workshop Infrastructures of Trading and Transferring Art since 1900 at the Central European Research Institute for Art History (KEMKI) – Museum of Fine Arts, Budapest, June 26-28, 2024. The workshop was organized by Gregor M. Langfeld (University of Amsterdam/Open University, Netherlands), Kristóf Nagy (Central European Research Institute for Art History (KEMKI) – Museum of Fine Arts, Hungary) and Lynn Rother (Leuphana University Lüneburg, Germany). This paper is the first account of my ongoing investigation into the history of artist-initiated institutions in Szentendre during the state socialist period. I began the research on the Szentendre Graphics Workshop and Gallery and the Artery Gallery based on the documents preserved in the archive of Pál Deim (1932–2016), painter and co-founder of the institutions in question, and I used the images of photographer Péter Deim (1959–2024). I would like to thank the following people and institutions for their support in the research: Emőke Bodonyi, Eszter Bohus, Ádám Farkas, Lajos Golovich, László Hajdú, József Mélyi, Johan van Dam, Tibor Wehner, and the Archive of Ferenczy Museum Center. I am also grateful for the reviewers for their constructive remarks, and Jakub Banasiak, chief editor of the academic journal Miejsce and the art magazine Szum. ↩︎

- Another art space operated under the same name in an apartment in Budapest, established in 1984 by the non-conformist Inconnu Group (Várnagy, “Láthatatlan történet”; Nagy and Szarvas, “Left Turn – Right Turn”; Cseh-Varga, “Turning Private into Public”). Some members of the Inconnu Group attended the opening of the Artery Gallery to discuss the issue and departed in agreement (Golovich, “Navigare necesse est!”). ↩︎

- The town of Szentendre played a key role in the development of one of the most influential avant-garde trends in Hungary, Dezső Korniss and Lajos Vajda’s “Szentendre program” in the 1930s, which aimed to create a unique Central Eastern European visual language by combining Western avant-garde art with local motifs. The program was continued in the endeavours of the European School between 1945-1948, a group of representatives of post-WWII progressive modern Hungarian art (1945–1948). These trends had a significant influence on the neo-avant-garde generation from the early 1960s onwards. See: György and Pataki, Az Európai Iskola; Petőcz and Szabó, Vajda Lajos – Világok között; Kolozsváry, Csak tiszta forrásból; Bodonyi and Pataki, Veszélyes csillagzat alatt. ↩︎

- Huth, “Képzőművészeti viták éskritikák,” 33–34. ↩︎

- Ibid., 28–29. ↩︎

- Ibid., 20. ↩︎

- Piotrowski, In the Shadow of Yalta; Mélyi, “Rendszerváltás”; Huth and Nagy, Kiállítások és kritikák. See also: Years of transition: the 1980s in Hungary and Eastern Europe, an ongoing research project on the visual arts in the 1980s in Hungary. Central European Research Institute for Art History (KEMKI) – Museum of Fine Arts. https://kemki.hu/research-department/60-Years_of_transition_the_1980s_in_Hungary_and_Eastern_Europe. ↩︎

- Mélyi, “Rendszerváltás.” ↩︎

- Hegyi, Újszenzibilitás. ↩︎

- Mélyi, “Rendszerváltás,” 16. ↩︎

- Németh, “A kortárs művészet megújulásának lehetőségei.” ↩︎

- Beke, “Rendszerváltozás.” ↩︎

- György Aczél (1917–1991) was Deputy Minister of Culture in 1958–1967 and he held various political positions overseeing culture until his retirement in 1989. Cultural politics in the 1960s–1970s was determined by his “3 t” principle – an abbreviation of “tiltott, tűrt, támogatott” (prohibited, tolerated, supported) – an arbitrary categorization of artists and forms of art. ↩︎

- Horváth, A művészek bevonulása; Fowkes, “Placing Bookmarks”; Kertész, A Képző- és Iparművészeti Lektorátus története; Huth, “Képzőművészeti viták és kritikák.” ↩︎

- Huth, “Képzőművészeti viták és kritikák.” ↩︎

- A m minisztertanács rendeletének végrehajtásáról szóló 16/1982. (XII. 29.) számú művelődési-miniszteri rendelet [Decree of the Minister of Culture No. 16/1982. (XII. 29.) on the Implementation of the Decree of the Council of Ministers]. In: Kertész, A Képző- és Iparművészeti Lektorátus története, 78.; Huth, “Képzőművészeti viták és kritikák,” 26. ↩︎

- MT rendelet a képzőművészet, az iparművészet, a fotóművészet és az ipari tervezőművészet egyes kérdéseinek szabályozásáról, 83/1982 (XII. 29) [Decree No. 83/1982 (XII. 29) on the Regulation of Issues of Fine Arts, Applied Arts, Photography and Industrial Design]. In: Kertész, A Képző- és Iparművészeti Lektorátus, 77; Huth, “Képzőművészeti viták és kritikák,” 28. ↩︎

- Menyhárt, “Aklotóközösségek”; Horváth, A művészek bevonulása, 219–221; Kertész, A Képző- és Iparművészeti Lektorátus története, 78; Huth, “Képzőművészeti viták és kritikák,” 27–28. ↩︎

- Szabó, “Termékenyítő légkör.” ↩︎

- Nagy, “Rabinec Studio”; Nagy, “Az eladásel égjó”; Huth,“ Képzőművészeti viták és kritikák,” 29–30. ↩︎

- The Fine Arts Fund merged with the Literature and Music Fund in 1968 and was renamed Magyar Népköztársaság Művészeti Alapja (Arts Fund of the People’s Republic of Hungary). After the regime change, it was transformed into Magyar Alkotóművészeti Közalapítvány (Public Foundation for Hungarian Artists) in 1992, and was terminated in 2012. ↩︎

- Huth, “Képzőművészeti viták és kritikák,” 23. ↩︎

- Ibid., 35. ↩︎

- Ibid., 28. ↩︎

- Esanu, The Postsocialist Contemporary. ↩︎

- How Eastern Europe got the Idea of Contemporary Art? Webinar organized by the Central European Research Institute for Art History (KEMKI) – Museum of Fine Arts, November 2, 2022. ↩︎

- The Soros Documentation Center documented the following members of the Artery Gallery in the 1980s: Imre Bak (member from 1990), Pál Deim (founding member), István Nádler (founding member) and János Szirtes (member from 1993) (Nagy, “A Soros Alapítvány,”197). The board members of the center between 1985-1988 included László Beke, Lóránd Hegyi, Márta Kovalovszky, Lajos Németh, and Júlia Szabó (Nagy, “From Fringe Interest to Hegemony”). ↩︎

- This information has been confirmed by Tibor Wehner via email on September 23, 2024. ↩︎

- For a detailed account on Hungarian art in this period, see: Knoll, Második nyilvánosság; Ars Hungarica 2011; Borus, Keretek között; Sasvári, Turai and Hornyik, Art in Hungary 1956–1980. ↩︎

- Tóth, A Szentendrei Régi Művésztelep. ↩︎

- Rappai, A Szentendrei Új Művésztelep. ↩︎

- See, for instance: Dudás, “Életműkiállítások.” ↩︎

- Members included: János Aknay, Péter Bereznai, Imre Bukta, Mihály Gubis, Csaba György (Borgó), László Győrffy, Ferenc Kis Tóth, Sándor Krizbai, Viktor Lois, László feLugossy, Gábor Matyófalvi (Matyó), Károly István Selényi, István Tóth, Ottó Vincze, András Wahorn, István ef Zámbó (Novotny and Wehner, A szentendrei Vajda Lajos Stúdió; Novotny, A szentendrei Vajda Lajos Stúdió). ↩︎

- Hornyik, “Budapesti Műhely.” ↩︎

- See, for instance: Barkóczi, “Creative (Dis)Courses”; Deim, “Amit nem lehet kiszerkeszteni.” ↩︎

- Andrási, “A Zuglói Kör (1958–1968)”; Andrási, “Zuglói Kör”; Hajdu, “Műtörténet borostyánba zárva”; Andrási, “Motívumrejtő absztrakció.” ↩︎

- The exact date of their collaboration is unknown but posters printed there for Ádám Farkas’s 1972 exhibition in Szentendre and a series of silkscreen prints he made in the Budapest Workshop in 1976, entitled The See, are indications. This information has been confirmed by Ádám Farkas via phone on February 13, 2025. ↩︎

- Deim, “Farkas Ádám emlékei.” ↩︎

- Imre Kocsis encountered the silkscreen technique in Belgium in 1972 and worked with it afterwards at his home studio. As an educator at the university’s mural workshop, he opened a silkscreen workshop there in 1978-1979 (Novotny, “Színre hangolt szitanyomatok”). ↩︎

- Deim, “Farkas Ádám emlékei.” ↩︎

- F. J., “Artéria: faltólfalig galéria.” ↩︎

- A Szentendrei Grafikai Műhely Működési Szabályzata [Operating Regulations of the Szentendre Graphic Workshop], June 30,1979. Archive of Ferenczy Museum Center, 4735-95/1–5. ↩︎

- According to László Hajdú’s recollection, the mayor of Szentendre between 1972–1985, Lajos Marosvölgyi, sold the building to the Arts Fund so the artists could use it as a workshop. Interview with László Hajdú via phone, February 18, 2025. ↩︎

- Hann, A Szentendrei Grafikai Műhely kiállítása; Novotny, “Színre hangolt szitanyomatok.” ↩︎

- The Pest County Bank of Artifacts was established to collect two copies of each print made in the Szentendre Graphics Workshop, in accordance with the state’s aspiration to popularize art (Hann, Szentendrei művészek grafikái). ↩︎

- Novotny, “Színre hangolt szitanyomatok.” ↩︎

- Members according to a 1991 list included János Aknay, Csaba Ásztai, László Balogh, Jenő Barcsay (died in 1988), József Bartl, József Baska, Endre Bálint (died in 1986), Ildikó Bálint, Péter Bereznai, István Bodóczky, László Borsódy, József Buhály, Imre Bukta, Pál Deim, Gábor Dienes, László Egyed, Ádám Farkas, Sándor Gavrilovics, István Gy. Molnár, Csaba György (Borgó), László Hajdú, György Hegyi, György Holdas, Piroska Jávor, Judit Kaponya, Ilona Keserü, Imre Kocsis, Dezső Korniss (died in 1984), Sándor Krizbai, Viktor Lois, László feLugossy, Endre Lukoviczky, Gábor Magyar, Gábor Matyófalvi, Dezső Mészáros, István Nádler, Rudolf Pacsika, Ervin Páljános, János Pirk, László Pirk, Anikó Rákosy, István Regős, Krisztina Rényi, Imre Szakáts, Imre Szánthó, Piroska Szántó (died in 1998), János Szirtes, Imre Szuromi, Miklós Szüts, Júlia Vajda (died in 1982), Erzsébet Vaszkó (died in 1986), Ottó Vince, András Wahorn, István ef Zámbó (Novotny, “Színre hangolt szitanyomatok”). ↩︎

- Deim, Interview with Ilona Keserü. ↩︎

- Deim,“Isten veled, Artéria Galéria!” ↩︎

- A grafikai műhelyhez kapcsolódó szentendrei kisgaléria tervezete [The concept of the graphic workshop’s accompanying gallery in Szentendre], September 1, 1979. Archive of Ferenczy Museum Center. ↩︎

- F. J., “Artéria: faltól falig galéria.” ↩︎

- Mazányi, Egytől egyig szita.; Novotny, “Színre hangolt szitanyomatok.” ↩︎

- See: documents stored in Pál Deim’s archive. ↩︎

- László Erdész managed the Workshop Gallery in 1981–1991. In 1991, he founded his private gallery together with his wife, Magdolna Ilosvai, under the name Erdész Galéria (Gallery Erdész). ↩︎

- Founding members included: János Aknay, Csaba Ásztai, Péter Bereznai, István Bodóczky, Imre Bukta, Simon Csorba, Pál Deim, Ádám Farkas, István Gy. Molnár, László Hajdú, Viktor Lois, László feLugossy, Gábor Magyar, Dezső Mészáros, István Nádler, János Pirk, László Pirk, Anikó Rákosy, István Regős, Krisztina Rényi, András Wahorn, István ef Zámbó. ↩︎

- Since the silkscreen workshop and the gallery had different leadership, the artists leaving the gallery did not quit their membership in the Szentendre Graphics Workshop. ↩︎

- Wehner, “A szentendrei Artéria Galéria.” ↩︎

- Deim, “Isten veled, Artéria Galéria!” ↩︎

- Group shows in the late 1980s and early 1990s included the following: Woerden, Stadsmuseum (1987), Miskolc, Miskolci Galéria (1987), Zalaegerszeg, Göcseji Múzeum (1987), Gyula, Erkel Ferenc Múzeum (1987), Cegléd, Ceglédi Galéria (1987), Szentendre, Vajda Lajos Stúdió Pinceműhely (1988), Pécs, Pécsi Galéria (1992), Budapest, Vigadó Galéria (1993), Szentendre, Szentendrei Képtár (1994). Solo shows were organized between 1986–1994 for János Aknay, Csaba Ásztai, Imre Bak, István Bodóczky, László Hajdu, Gábor Magyar, István Nádler, László Pirk, Anikó Rákosy, András Wahorn (Wehner, “Artéria Galéria dokumentáció”). ↩︎

- This information has been confirmed by Tibor Wehner via email on February 6, 2025. ↩︎

- Wehner, A szentendrei Artéria Galéria kiállítása. ↩︎

- Golovich, “Navigare necesse est!” ↩︎

- Johan Van Dam’s letter to the members of Artery Gallery (manuscript), July 13, 1990. Archive of Ferenczy Museum Center 4769-95/1–5. ↩︎

- Wehner, “Artéria Galéria dokumentáció.” ↩︎

- Chikán, “Régi-új Artéria.” ↩︎

- This information has been confirmed by László Hajdú via phone on February 18, 2025. ↩︎

- During this period, the gallery presented solo shows for József Baksai, Zoltán Bánföldi, Ágnes Deli, Ádám Farkas, István Gy. Molnár, István Haász, László Hajdu, Krisztina Lehoczky, Tibor Lukács, Viktor Lois, Attila Orbán, István Regős, as well as a group exhibition celebrating the 20th anniversary of the gallery’s foundation in 2006, entitled 1986–2006 – 20 éves az Artéria Galéria [1986–2006 – The Artery Gallery is 20 Years Old] (Wehner, “Artéria Galéria dokumentáció”). ↩︎

- The publication (Bohus, Akció és reakció) would have contained a preface by Pál Deim (Deim 2016 [2008]), five chapters, which were drafted as manuscripts or notes, and an overview of the artists. The planned chapters were the following: art in Szentendre in the 20th century by Emőke Bodonyi (“Szentendre és a képzőművészet”), the history of the Artery Gallery by Tibor Wehner (notes), performance art represented by some members of the gallery, by István Juszuf Antal (“Performerek az Artéria Galéria körül”), the transformation of art trade between the 1950s and the 2000s by Lajos Golovich (“Navigare necesse est”), and relevant artistic trends by József Bárdosi (“Hajszálértől az Artérián túl”). Eszter Bohus tried to find sponsors to publish the book, which was supported by the Nemzeti Kulturális Alap (National Cultural Fund) and the Magyar Tudományos Akadémia Bölcsészettödományi Kutatóközpont (Research Center of Humanities – Hungarian Academy of Sciences), and László Beke wrote a recommendation for it. See: Eszter Bohus’s book proposal for sponsors entitled Könyvtámogatási kiajánló (manuscript in Pál Deim’s archive). The manuscripts and notes prepared for the publication are the courtesy of Johan van Dam and held in Pál Deim’s archive. ↩︎

Réka Deim

Réka Deim is an art historian and a PhD candidate at the Amsterdam School for Heritage, Memory and Material Culture, University of Amsterdam. She obtained an MA degree in Cultural Analysis at the University of Amsterdam (2013), having previously completed master’s programmes in Art History and English Literary Studies in Budapest (2011). Her research revolves around post-war art and memory politics in Central and Eastern Europe, and she has briefly studied Latin American memory cultures at the University of Buenos Aires and the National University of Colombia. Alongside developing her PhD project on the contemporary politics of memory in Hungary, she has been publishing articles in art magazines ArtPortal and Balkon. She has recently curated the retrospective exhibitions of Pál Deim and József Bartl, and edited the accompanying oeuvre catalogues in collaboration with the Ferenczy Museum Center (2022, 2024).