Title

Transformation and Transition On the Liberal Politics of Visibility in Polish Art During the Transformation Period Through the Lens of Alicja Żebrowska’s Works

https://doi.org/10.48285/ASPWAW.29564158.MCE.2024.10.7EN

1990s, trans studies, transformation, body art, critical art, Alicja Żebrowska

https://miejsce.asp.waw.pl/en/transformacja-i-tranzycja/

Abstract

This article examines the visual strategies of representing trans women in 1990s body art, as well as the critical reception of these depictions. It offers a close analysis of two series of works by Alicja Żebrowska: „Onone. Świat po świecie” [Onone. A World after the World] (1995–1999) and „Kiedy inny staje się swoim” [When the Other Becomes One of Us] (1998–2002), alongside their accompanying texts. Adopting a feminist and materialist perspective (Heaney 2017, Gabriel 2024), we follow the process of stripping trans femininity of its materi-al contingencies in order to construct a symbolic figure of systemic transformation. As we demonstrate, this allegorical distillation of trans femininity is predicated on a conventional understanding of the body as an object deprived of agency and subjected to perpetual manip-ulation within the paradigm of so-called critical art. Consequently, trans individuals are posi-tioned as the “Other” – not only outside the social order but also beyond the framework of sexual difference. The epistemological horizon of these representations is shaped by a teleo-logical and liberal conception of inclusion, predicated on greater visibility of marginalized sub-jects in mainstream media, public imagery (e.g. billboard campaigns), and ultimately, within the sphere of art. However, as we argue, this model of visibility operates at the expense of trans individuals as autonomous subjects, actively experiencing and participating in historical transformations. In conclusion, we contextualize the emergence of new representations of transgender identity in relation to evolving – and oppressive – legal frameworks that structure the conditions of trans women’s lives (Debińska 2020, Charkiewicz 2009).

Keywords

1990s, trans studies, transformation, body art, critical art, Alicja Żebrowska

DOI

Introduction

In 2007, Krytyka Polityczna published Artur Żmijewski’s manifesto Stosowane sztuki społeczne [Applied Social Arts]. The text culminated with the following assertion:

Our collective loss […] is the failure to take a step towards the application on a wider scale of the cognitive procedures developed by art – procedures based on intuition and imagination, on the negation of one’s own nobility and the abandonment of the role of judge.1

According to Żmijewski, the “cognitive procedures” – that is, the creative methodologies developed in the 1990s – remained relevant. However, he simultaneously advocated for a fundamental correction. The context in which this manifesto was published was Poland’s accession to the European Union (2004) and the rise to power of a coalition government led by Law and Justice, the League of Polish Families, and Self-Defense (2005). The ascendance of these populist and right-wing parties cast doubt upon the viability of the liberal democracy model in Poland. Reflecting on the „social consequences” of the artistic language chosen in the 1990s, which he regarded as actively shaping social reality, Żmijewski observed that “the violation of certain taboos results in the creation of new ones. Art may have contributed precisely to such a shift on the map – to the undermining of some aspects of the social body and the tabooization of others.” And most crucially: any political “shift on the map” requires art to “change the protagonist – the shape of reality depends on the ‘invisible majority’ rather than on ‘exotic exceptions.’”2

The shift in emphasis proposed by Żmijewski is of fundamental significance. In his vision, the “exotic exceptions” that had previously appeared in art projects within the sphere of so-called critical art – such as people with disabilities, the chronically ill, the elderly, or trans – are deemed visually marginal and, by extension, politically ineffectual. They are contrasted with the “invisible majority” – composed of more socially dominant groups or classes. (This is why Żmijewski wrote favorably about Julita Wójcik’s Obieranie ziemniaków [Peeling Potatoes] as a project that elevates the mundane and the quotidian while adhering to the critical art model of “increasing visibility.”) For Żmijewski, political agency within a democratic system is located precisely within this majority.3

Although the quoted passage is peripheral to Żmijewski’s broader argument, the dualism it articulates is highly symptomatic, as it recurs in the writings of other authors from the period. At its core lies the opposition between symbolic struggle (identity politics) and socio-economic struggle, with the former increasingly devalued as being incompatible with the lived experience of the working classes.4 This shift marks a fundamental transformation in the very object of emancipation and, concomitantly, of representation.

We argue that within that debate on the evolving strategies of socially engaged art, a crucial dimension was overlooked: the epistemic limits of the artistic and discursive practices already in circulation. This article examines Alicja Żebrowska’s works, which feature one of the aforementioned „exotic exceptions” – the trans woman, whether explicitly or through suggestion. Through an analysis of the critical reception of the series Onone. Świat po świecie [Onone. A World after the World] (1995–1999) and Kiedy inny staje się swoim [When the Other Becomes One of Us] (1998–2002), we identify three interpretative tropes that have remained largely absent from discussions concerning late 1990s and early 2000s art. First, we argue that the allegory of trans femininity and the figure of androgyny (or bisexuality) were used to articulate the experience of transformation.5 Second, these figures functioned as a litmus test for measuring the perceived progressiveness of the art world. Third, this particular conceptualization of trans femininity was contingent upon its treatment as a symbol, not as the actual condition of people participating in historical transformations.

The perception of trans femininity as a figure that bridges gender and historical transformation has a long and multifaceted tradition. This lineage weaves together twentieth-century sexology, interwar avant-garde art, and the queer theoretical discourse of the 1990s. As American literary scholar Emma Heaney observes in The New Woman: Literary Modernism, Queer Theory, and the Trans Feminine Allegory:

Through the medical conceit of the woman trapped in a male body sexologists distilled the variety of trans feminine experience into this single entrapped figure that novelists and theorists then installed in fictional and theoretical narratives about gender, desire, and historical change.6

The very instability of meanings attributed to the trans feminine allegory also proved instrumental in Poland during the political transformation.

As we will demonstrate, the representation of trans femininity in the art and art criticism of the 1990s and 2000s was grounded in the perception of the body as an object devoid of agency, subjected to relentless manipulation, and consequently requiring critical intervention7 – i.e. a perception that prevailed within so-called critical art. This mode of engaging with the body can be characterized as disembodied. However, as literary scholar Kay Gabriel observes, the body as an object of inquiry need not be approached as “a dead empirical fact, as something given or unchanging, but […] as a site of agency, constraint, and social signification – subject to dispossession, wrung for its resources, and the object of immense and intensive social struggle.”8 This reconceptualization allows us to move beyond a framework in which the “Other” is imagined as an external specter haunting society to one where it is recognized as a agential body. This text seeks to extend such a perspective to Polish critical art.

Androgyny vs. trans femininity: Onone

The Onone series was created in several phases between 1995 and 1999. Initially conceived as a science-fiction film inspired by a dream, the project ultimately materialized as a short video and a series of 18 photographs portraying the eponymous Onone – a techno-biological hybrid of ambiguous gender.

Żebrowska’s series started from her deep fascination with esotericism, particularly with the figure of the androgyne, but also stemmed from a specific real-world encounter: a meeting with a trans woman in a nightclub.9 Onone possesses a distinctly feminine form, complete with breasts, yet is also depicted with a long penis. The individual works in the series bear enigmatic Latin titles – Autoholos, Sexfantilis, Nekroinfanticus, etc. – with the figure of the androgyne arranged in a mystical cycle of life and death. Across successive images, the hybrid is depicted as engaged in everyday activities: gazing into a mirror, merging with a techno-biological landscape, masturbating, or undergoing hypnosis. Onone’s trajectory culminates in a cosmic transfiguration – ascending into space and dissolving into a higher form of existence, ultimately unifying with the universe.

Alicja Żebrowska, Onone – The World After the World / Assimilatio I, 1995, analog photograph, lightbox, 150 × 150 cm, courtesy of the artist

Visually and symbolically dense, Żebrowska’s enigmatic vision has received relatively little critical interpretation. One of the most insightful comes from Hartmut Böhme, a German scholar of modernism, who, in an essay published in Magazyn Sztuki in 1997, identified in it motifs such as an allegory of the creative process, an exploration of female sexuality and sexual infantility, and a primordial mode of organizing desire.10 At the same time, Böhme connects this fluidity of meaning to transsexuality, interpreting Onone through the lens of literary modernism. He mentions Musil’s Unions and Virginia Woolf’s Orlando, situating Żebrowska’s work within a broader tradition of modernist gender ambiguity. As Emma Heaney observes, “Modernists ascribe to […] trans feminine allegory the qualities of corporeality, essential sexuality, and enigmatic ‘absolute otherness’ as naturalized features of her very status as a trans woman.”11 This is possible thanks to an act of extracting the trans woman from everyday life and from the material conditions that shape her existence, which is enabled by the recourse to aseptic medical categorizations.

In a similar manner – though within a different conceptual register – the category of trans femininity appears in the writing of Paweł Leszkowicz. His essay “Po obu stronach lustra – w poszukiwaniu seksualności trzeciego tysiąclecia” [On Both Sides of the Mirror – In Search of Third Millennium Sexuality], published in the catalog for Żebrowska’s exhibition Onone. Świat po świecie (Center for Contemporary Art Ujazdowski Castle, 1997), represents one of the earliest attempts to articulate a discourse on this subject within the transformative domain of contemporary art. Leszkowicz describes Żebrowska’s series as

[…] a self-erotic and androgynous vision of a “world for oneself” and simultaneously a visually seductive, unrestrained futuristic fairy tale for the audience. Onone is the embodiment of an individual dream, resonating with the mystical Platonic ideal of unity of sexual dichotomies, fulfilling the feminist demand for gender fluidity, and enacting the ceaseless interpenetration of femininity and masculinity within the identity of a human being striving to meet the expectations of the contemporary epoch. […] Through hypnosis and dream states, Alicja conjured a utopia and a new genetic mutation, offering solace in a fractured and fallen world. Paradoxically, the faint melancholy that at times lingers on Onone’s faces may signify precisely a yearning for pain and separation. It is a shadow of doubt, questioning the very fabric of the ideal, disrupting its phantasmatic coherence, an imperfection ineradicable within a culture that has supplanted the binary completeness and the androgyny with the performative spectacle of transvestism and the tragedy of transsexualism. This ambivalence permeates the figure of Onone, inscribing itself upon her enigmatic, uncanny corporeality and the veiled opacity of her existence.12

Leszkowicz thus outlines a distinctive evolution of the bisexual paradigm of human subjectivity – a progression from the Platonic ideal of sexual completeness, through the conservative fragmentation of that whole into dichotomous opposites, toward the “feminist demand for gender flexibility.” In other words, androgyny emerges as a state that aligns with the “requirements of modernity” – in this case, a transformation toward capitalism and democracy. Concurrently, the ideal of gender bisexuality is juxtaposed with bodily modifications, which are framed as “the spectacle of transvestism” and “the tragedy of transsexualism.” Thus, one could argue that the first model, which Leszkowicz implicitly valorizes (as a fluid and mutable subject), encapsulates the defining characteristics of ongoing change. By contrast, the transsexual subject13 appears almost reactionary: their desire not only repudiates the principle of fluid subjectivity but also seeks to re-establish fixity where perpetual flux is presumed normative. Against the backdrop of the androgyne’s flexible sexuality, the transsexual subject – theatrically hyperbolic in its gendered embodiment – is also an anachronistic figure. Trans femininity – embodied transformation, conceived by Leszkowicz as an assertion of stability – is unsuitable for the narrative of ceaseless transformation.

As Emma Heaney observes, the allegory of the trans femininity recurs in moments of historical uncertainty, serving as a vehicle through which the anxieties and tensions of transitional periods are articulated via an “enigmatic” corporeality.14 This function appears to be at work in Leszkowicz’s essay as well. He is, of course, neither the first nor the only theorist to conceptualize trans womanhood in this manner. The author of Nagi mężczyzna [The Naked Man] situates himself within an interpretive framework shaped at the intersection of psychoanalysis, sexology, and modernist literature, later echoed in the queer theoretical discourses of the 1990s (as the “expert trans feminine”). According to Heaney, this figure presupposes the impossibility of accessing an essentialized trans femininity, which would make the meanings attributed to trans femininity extend beyond individuals who explicitly identified as trans women and onto those whose bodies or identities are merely perceived through that lens. It is this very principle that seemingly enabled Leszkowicz to inscribe Onone – even if “ambivalently” – within the allegorical framework of trans femininity. This, in turn, allowed him to extrapolate a broader metaphor of modernity as an idealized fullness, a seamless and rational synthesis of two systems. By contrast, transsexuality is positioned as an expression of incongruence with the logic of transformative change.

From Document to Intervention: Kiedy inny staje się swoim

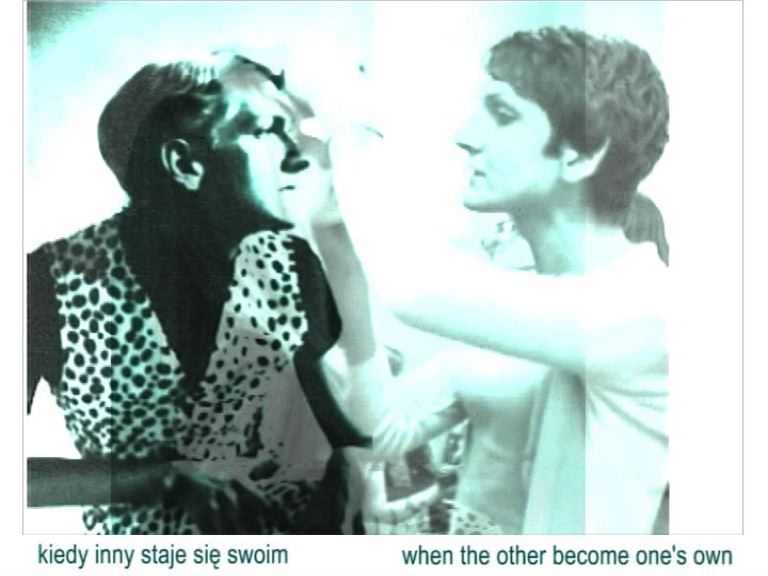

The series Kiedy inny staje się swoim [When the Other Becomes One of Us] was created between 1998 and 2002. Once again, its genesis lay in an encounter with a trans woman – this time, it was Sara, a friend of the family. The collaboration between Żebrowska and Sara over the years culminated in two video works, a photographic series, and a billboard advertising campaign.

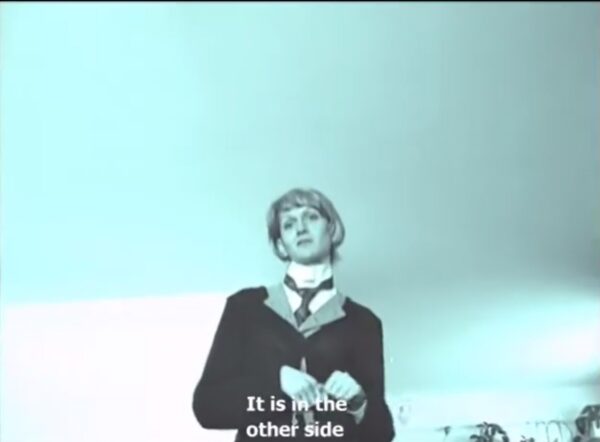

Alicja Żebrowska, still from the video series When the Other Becomes One’s Own, 1998–2002, VHS video, collection of the Museum of Modern Art in Warsaw, courtesy of the artist

Kiedy inny… offers a multifaceted portrayal of trans femininity, chronicling Sara’s lived experience in various ways and through different media. The project explores the transition process as a “journey,” from the depiction of sex reassignment surgery (SRS) to the documentation of Sara’s gestures and behaviors in her professional environment.

The photographic series was created in the artist’s former apartment in Kraków in collaboration with Dariusz Baster, Żebrowska’s longtime creative partner and the composer of the soundtrack for the Onone video series. The culmination of their joint efforts was a triptych intended for display in lightboxes, portraying a nude Sara enveloped by rich purple fabrics as she gazes into an elongated mirror placed before her. In the first photograph, the model reclines against a piece of furniture, her gaze meeting her own reflection in the mirror with an air of confidence. In the second, now wrapped in a blue cloth, she twists toward the camera, contorted on the ground. In the third, she turns toward the viewer, this time entirely uncovered, her legs drawn closer to her chest, her hand resting on her face in a gesture suggesting exhaustion. Through this progression, Żebrowska captures the tension between Sara’s internal perception of her body and its external representation, shown using the classical metaphor of the mirror. The compositional structure of the triptych also evokes the iconographic motif of Venus. Sara therefore becomes part of the modern history of the female nude, which, because of its tradition, confers an ennobling quality upon the model and consequently – the transsexual body.

Sara’s corporeality – her gestures, movements, and interactions with others – serves as the central thematic thread of Kiedy inny…. This is particularly pronounced in the video summarizing the model’s years-long collaboration with the artist. The 17-minute footage follows Sara performing her work as a stylist, model, and on-set assistant, registers her conversations with the artist, shows images from her modeling portfolio, and her own interactions with other models. Much like the photographic series, the video employs the mirror as a metaphor for the incongruity between internal identity and the external form. Żebrowska achieved this effect by strategically reflecting the image along the vertical axis at selected moments, enabling her to scrutinize Sara’s gestures in succession by placing them in direct juxtaposition, contrasting her body with those of the men working on set, and layering successive shots to construct a catalog of movements and behaviors. Through this approach, the work encourages reflection on which parts of the body and relations with them delineate gendered experience.

The relationships cultivated by Sara, along with the way she moves, serve as significant gender markers, and as such are noticed by Żebrowska. They define Sara’s femininity, both within and beyond the workplace.

However, even this seemingly cohesive vision is deliberately fractured by the artist, who disrupts the scene’s naturalistic atmosphere by overlaying it with audio recorded during an incidental gynecological procedure at a Kraków clinic. In doing so, does Żebrowska highlight the operation as a pivotal moment in the gender transition process while sidelining other dimensions of gendered experience? Or does she instead complicate the very notion of transition? A filmed interview with Sara, conducted in the artist’s apartment, may offer insight into this tension.

In this five-minute video, filtered through an unnatural green hue, a woman in heavy heels paces in circles around the living room, moving in front of Żebrowska, who remains unseen, seated behind the camera. Sara is wearing a buttoned shirt with a slim tie, a fitted jacket, and a skirt. When she speaks, she rarely directs her gaze toward the camera, and when she does, it is with an assertive, almost defiant stare – her responses oscillate between playfulness, nonchalance, and restrained fury. Instead of focusing on her facial expressions or gesticulations, Żebrowska at times tilts the camera downward, capturing the movement of her legs, emphasizing her gait as a defining feature of her embodied identity. In the background, the kitchen is visible through an open doorway, where a man – presumably Dariusz Baster – is sitting at the table. Sara moves between him, Żebrowska, and the door to another room.

The film’s editing deliberately disrupts the flow of the conversation. We hear only Sara’s statements, left to infer Żebrowska’s questions. The model mentions her surgery, the “exaggerating of some sacrifices,” her aversion to men and the discomfort she experiences in their presence, as well as the process of undergoing sexological evaluations and her evolving relationship with her own body. Or rather: we are forced to reconstruct these themes by ourselves, piecing together Sara’s fragmented sentences and frames disjointed by Żebrowska. The latter frequently turns Sara’s words into provocative, often ironic statements: “A normal girl / feels like a man”; “Tired / Confused / Urological / Desperate.”

Alicja Żebrowska in collaboration with Dariusz Baster, When the Other Becomes One’s Own, 1999, analog photograph, 180 × 120 cm, collection of Bunkier Sztuki, courtesy of the artist

We contend that while Kiedy inny… may be interpreted as an exercise in artistic overreach – where Żebrowska appears to dictate Sara’s narrative, presuming to know what she should express – it simultaneously engages a multiplicity of strategies for working with, and depicting, trans femininity. At the same time, Żebrowska introduces significant interventions into the language of documentary film, undermining its traditional claim to objectivity as a “neutral representation of reality.”15 In doing so, Sara’s transition is decoupled from the schema of genital difference: of equal importance are the broader social dimensions of her lived experience, her emotional landscape, and personal well-being. However, as we shall see, transformative art criticism has largely misread this approach, reducing Kiedy inny… to yet another representation of “Otherness.”

Visibility as Emancipation

Originally, the series Kiedy inny staje się swoim was slated for presentation at the 2nd Photo Biennale in Poznań “Krystalizacje” [Crystallizations] (2000).

Alicja Żebrowska, photograph from the billboard series When the Other Becomes One’s Own, 2000, analog photograph, courtesy of the artist

This was not to be.16 Instead, selected elements of the project were exhibited in group shows in Gdańsk (2000) and Kraków (2001), before finally receiving a dedicated exhibition at the CCA Łaźnia in Gdańsk in 2002, curated by Bożena Czubak. Thus, although largely forgotten today, the series was noted in the early 2000s,17 as evidenced by the number of critical texts and media coverage it generated. Yet, unlike in Leszkowicz’s vision, which conceptualizes trans femininity as a metaphor for the unpredictability of transformation, critical discourse surrounding Kiedy inny… tended to reduce the trans woman to a symbolic “Other” of the era. A telling example of this interpretive tendency can be found in Piotr Piotrowski’s essay Sztuka według polityki [Art According to Politics], published in the catalog accompanying the exhibition Negocjatorzy sztuki. Wobec rzeczywistości [Negotiators of Art. In the Face of Reality] at the CCA Łaźnia in 2000. Discussing Żebrowska’s work, Piotrowski writes:

A transvestite – especially one who „truly” becomes a woman through medical intervention – embodies this conviction and becomes particularly threatening to the authorities. Authoritarian regimes accuse such individuals of violating legal norms and criminalize them. More liberal systems, while compelled to tolerate their existence, nonetheless recognize their subversive potential and employ repressive mechanisms to contain it, framing it as „abhorrent” and relegating it to the realm of privacy, which is intended to neutralize the disruptive power of the phenomenon. The insistence that “these are personal matters” functions as a means of expelling the issue from the public sphere and, in doing so, stripping it of its broader political implications.18

Piotrowski thus focuses on the political significance of trans femininity, ascribing to it an inherently revolutionary character. In his reading, Sara „materializes the conviction” that changing sex is possible, which is a threat to the system. The adaptation of genitalia is framed as the definitive, ultimate dimension of transition. Consequently, Piotrowski conceptualizes the trans woman as “absolutely different” from the rest of society, positioning her, through his use of genderless language, beyond the conventional binary of gender. It is precisely this perspective that enables the fantasy of the subversive potential of sex reassignment and its subject: the “transvestite.”19 Within Piotrowski’s framework, this figure exists entirely outside of social reality, and thus, by extension, beyond the reach of dominant ideology. By centering genital surgery as an emblem of liberation from gender, the critic portrays transsexuality as revolutionary in and of itself. However, this perspective erases the fact that trans bodies and desires are deeply embedded in social networks – that trans people experience social transformation, not just represent them.20

Bożena Czubak offers a similar interpretation. In her introduction to the Negocjatorzy sztuki catalog, she argues that Żebrowska, by “moving away from cultural compensations [in Onone] to reality in Kiedy inny staje się swoim, moves from questions of transgression into Otherness to inquiries about how to become ‘one of us,’ how to negotiate a place for Otherness.”21 Once again, this is presumed to occur through the heightened visibility of the trans woman’s body.

Łukasz Gazur, in turn, observes that Żebrowska’s work attempts to both negotiate and “demystify the ‘freak’ figure exiting within the social imagination” by integrating it into the canonical tradition of the female nude.22 In this approach – as in the interpretations offered by Piotrowski and Czubak – the visibility of the trans body to a wider audience is supposed to transform the “Other” into “one of us,” thereby establishing a new political horizon. Here, inclusion of marginalized individuals is envisioned as a function of increased visibility, achieved through representation in mainstream media and public imagery (e.g., billboards), and ultimately, within the realm of art. In other words, in the critical art discourse, the visual presence of “Otherness” is regarded as a marker of the success of a broader transformative modernization toward Western liberal “normality.”23

Yet, the vision of inclusion articulated by art criticism and art history through the logic of greater visibility rested on a fundamental preconception. As the editors of Trap Door argue, “representation is said to remedy broader acute social crises, […] particularly when representation is taken up as a ‘teaching tool’ that allows those outside our immediate social worlds and identities to glimpse some notion of shared humanity.”24 Liberal politics of visibility, in which body art and its critical reception have been active participants, often substitutes material concerns of social justice with a form of crisis management: if a group is excluded, simply increase its visibility. Under this model, critical art assumes a didactic function, fulfilled within the context of a gallery as a self-styled “laboratory of social change.”25 This space, positioned as a site for producing a tolerant, “European” subject, ultimately adheres to the regulative ideal of bourgeois “good education” rather than showing a real interest in the lived realities of those represented in “critical” works. Under the laboratory conditions of body art, the gallery audience is free to project any meaning onto the image of Żebrowska’s protagonist. This raises a fundamental question about who, in reality, is the subject of liberal visibility politics – the aspiring, “modern” middle class (the gallery-goers) or the non-normative bodies that exist in reality?

The discourse of a transformative art history ascribed political power not only to the trans body but, more broadly, to what Izabela Kowalczyk describes as “the body that defies norms […]; the body of the ‘Other.’” Later in the introduction to the exhibition catalog Niebezpiecznie związki sztuki z ciałem [Dangerous Relationships between Art and the Body], Kowalczyk acknowledges that critical art “is not so much about the body itself but rather about […] reflections on the human condition, on the existence of modern man.”26 Indeed, the curatorial and artistic project of the “gallery of Otherness,” carried out by curators and artists in the 1990s and 2000s, frequently relied on disembodied representations. Within this framework, the visual presence of non-normative bodies and the subsequent imposition of political meanings upon them risked overshadowing the fact that those very same bodies are active participants in, and subjects of, broader social transformations.

Katarzyna Kozyra, still from the video Men’s Bathhouse, 1999, VHS video, 5-channel video installation, collection of Zachęta – National Gallery of Art, courtesy of the Katarzyna Kozyra Foundation

Transition in times of transformation. Conclusion

The allegorizing practices analyzed in the article are actually intended to strip the experience of trans femininity of its social determinants. While artists and critics were busied themselves exploring representations of non-normative bodies, expert discourses on transness were undergoing rapid transformation. According to Maria Debińska’s research, this shift began as early as the second half of the 1980s:

What used to be a focus on the right to self-determination and personal dignity of transgender people, and the state’s role in supporting individuals against an oppressive society, has shifted toward framing transgenderism as a disruption of family and social relations, and as a threat posed by transgender people to both the state’s legal order and their immediate environment.27

The sexological – and what researchers refer to as the humanistic28 – model of social inclusion of trans people came under criticism in legal debates concerning the institutional practices of gender realignment, both administrative and medical. During the transformation period, legal discourse began to interpret gender reassignment as a threat to the cohesiveness of society.29 Transsexuals were seen not only as a danger to their loved ones and the “social order,” but also as a threat to themselves. In light of a peculiar interpretation of Article 155 of the Penal Code, genital alteration surgery became controversial and was classified as an instance of grave bodily harm. As Dębińska notes, this restrictive reading of the provision turned reproductive functions into an object of both social and legal protection, endowing them with an almost sacred status.30

Changes continued throughout the 1990s. In 1989, the Supreme Court, responding to an inquiry submitted by the Attorney General, declared that gender designation in official documents could not be changed at all.31 In 1996, another Supreme Court ruling gave rise to an improvised legal practice – still in place today – according to which trans individuals sue their parents in a gender determination lawsuit, which is framed as a measure to protect personal rights. In 1999, i.e. when Kiedy inny staje się swoim was being created, the government of Jerzy Buzek launched a neoliberal reform of the health care system. As economist Ewa Charkiewicz observes, this marked a shift in how the tasks and goals of health assistance were understood:

The health care reform did not begin with an assessment of the resources of medical facilities or the population’s medical needs in order to respond effectively and efficiently. Instead, it began with establishing a new norm: the assumption that health care should operate as a market for medical services, that expenditures should be covered by insurance contributions, and that the state’s share of funding should be minimized. […] According to neoliberal economists and politicians, only those services that are unprofitable for private companies should receive public funding. The pressure to reduce costs, however, does not apply to drug reimbursements, which continue to rise. In this model, economic efficiency is not a means but an end in itself, and medical institutions, compelled to restructure under financial constraints, are transformed into machines for generating profit. Health becomes a commodity, accessible through private subscription for those who can afford the insurance premiums. Economic efficiency produces social inefficiency, as the pursuit of maximum gain and competitiveness generates relentless pressure to cut costs.32

As part of this process, the medical procedure for sex reassignment – previously covered by insurance33 – was removed from the list of reimbursable treatments. The costs of transition were shifted entirely onto individuals. In other words, only the wealthiest members of Polish society could henceforth afford to transition. None of these issues – central to the lives of trans people – served as a point of reference for art criticism or art history. In the interpretations offered by Paweł Leszkowicz and Piotr Piotrowski, trans femininity was presented not only as a figure situated outside actual social conditions, but also one that destabilizes them in various ways. Bożena Czubak, by contrast, articulates a vision of inclusion of the “Other” through the public visibility of images of their bodies.

All three of these positions – central to the art discourse of the late 1990s and 2000s – are grounded in a belief in the causality of representation. But what if critical art and its accompanying theory do not, in fact, lead to social and political modernization (the position of trans, disabled and elderly people remains unchanged to this day)? Artur Żmijewski argued that, in such a case, one should simply “change the protagonist.” This article proposes a different approach: an analysis of the historical (social and economic) conditions surrounding both the transformation of the “Other” and the works and interpretations that address it. If we do so, we may find that the social worlds from which non-normative bodies emerge are richer and far more complex than previous analyses suggested.

Translated by Karol Waniek

Bibliography:

Böhme, Hartmut. „Podróż do wnętrza ciała i jeszcze dalej. Sztuka Alicji Żebrowskiej.” Translated by Aleksandra Ubertowska. Art Magazine, no. 1–2 (1997).

Charkiewicz, Ewa. „Ekonomia opieki i reforma systemu ochrony zdrowia.” In Gender i ekonomia opieki, edited by Ewa Charkiewicz and Anna Zachorowska-Mazurkiewicz. Warsaw: Think Tank Feminist Library, 2009.

Czubak, Bożena. „Wobec rzeczywistości.” In Negocjatorzy sztuki wobec rzeczywistości, edited by Bożena Czubak. Gdańsk: Centrum Sztuki Współczesnej Łaźnia, 2000.

Dębińska, Maria. Transpłciowość w Polsce. Wytwarzanie kategorii. Warsaw: Wydawnictwo Instytutu Archeologii i Etnologii Polskiej Akademii Nauk, 2020.

Gabriel, Kay. „Two Senses of Gender Abolition: Gender as Accumulation Strategy.” In Feminism Against Cisness, edited by Emma Heaney. Durham–London: Duke University Press, 2024.

Gazur, Łukasz. „Eksplozja świetnej sztuki.” Gazeta Antykwaryczna Sztuka.pl, no. 1/2 (2006).

Gossett, Reina, Eric A. Stanley, and Johanna Burton, eds. Trap Door: Trans Cultural Production and the Politics of Visibility. Boston: Massachusetts Institute of Technology, 2017.

Heaney, Emma. The New Woman: Literary Modernism, Queer Theory and the Trans Feminine Allegory. Evanston: Northwestern University Press, 2017.

Iwanczewska, Łucja. Potencjalności transformacji. Krótkie trwanie performansów kulturowych w Polsce lat 90. Warsaw: Instytut Badań Literackich Polskiej Akademii Nauk, 2022.

Jakubowicz, Rafał. „Robotnicyzm. Sztuka w ujęciu radykalnym.” In Wyparte dyskursy. Sztuka wobec zmian społecznych i dezindustrializacji lat 90., edited by Michał Iwański. Szczecin: Wydawnictwo Akademii Sztuki w Szczecinie, 2016.

Janion, Ludmiła. „ ‘Transsexuality’ and Gender Ratio in Poland: A Case Study on the East/West Dichotomy.” Journal of Homosexuality 70, no. 11 (2023): 2539–2559.

Kowalczyk, Izabela. Ciało i władza. Polska sztuka krytyczna lat 90. Warsaw: Wydawnictwo Sic! s.c., 2002.

Kowalczyk, Izabela. „Wstęp.” In Niebezpiecznych związków sztuki z ciałem, edited by Izabela Kowalczyk. Poznań: Galeria Miejska Arsenał, 2002.

Leszkowicz, Paweł. „Czy twój umysł jest pełen dobroci?” https://archiwum-obieg.u-jazdowski.pl/teksty/5766. Accessed September 2, 2024.

Leszkowicz, Paweł. Curatorial text for the exhibition Onone. Świat po świecie. Warsaw: CCA Ujazdowski Castle, 1997.

Majewska, Ewa. Sztuka jako pozór? Cenzura i inne paradoksy upolitycznienia kultury. Kraków: Wydawnictwo Ha!art, 2013.

Miękkie, twarde; penetrowalne, zdolne do penetracji. Ciała przeciwko cisowości. Translated by Łucja Staszkiewicz. https://machinamysli.org/miekkie-twarde-penetrowalne-zdolne-do-penetracji-ciala-przeciwko-cisowosci/. Accessed September 2, 2024.

Mishtal, Joanna. The Politics of Morality: The Church, the State, and Reproductive Rights in Postsocialist Poland. Athens: Ohio University Press, 2015.

Monfort, Bruno. „The Political Economy of Sexual Identity: From Gender Performativity to Social Reproduction.” Transgender Studies Quarterly 11, no. 2 (2024): 266–286.

Piotrowski, Piotr. „Sztuka według polityki.” In Negocjatorzy sztuki wobec rzeczywistości, edited by Bożena Czubak. Gdańsk: Centrum Sztuki Współczesnej Łaźnia, 2000.

Pospiszyl, Michał. „Sztuka instytucji mniejszych.” Dialog. Miesięcznik poświęcony dramaturgii współczesnej, no. 11(732) (2017): 152–167.

Szcześniak, Magda. Normy widzialności. Tożsamość w czasach transformacji. Warsaw: Fundacja Bęc Zmiana, Instytut Kultury Polskiej, 2016.

Szreder, Kuba. „Pożegnanie z latami 90. W poszukiwaniu nowych formuł zaangażowania.” In Na okrągło: 1989–2009, edited by Jan Sowa and Andrzej Szyłak. Kraków–Wrocław: Korporacja Ha!art, BWA Wrocław, 2009.

„Teraz Kozyra? Polska performerka i jej promotorzy próbują epatować tanimi, przebrzmiałymi chwytami.” Życie, June 1, 1999.

The New Woman: Literary Modernism, Queer Theory and the Trans Feminine Allegory. Evanston: Northwestern University Press, 2017.

Transgender Marxism, edited by Jules Joanne Gleeson and Elle O’Rourke. London: Pluto Press, 2021.

Wyszyńska, Małgorzata. „Zgorszenia nie będzie.” https://classic.wyborcza.pl/archiwumGW/1080321/Zgorszenia-nie-bedzie. Accessed September 2, 2024.

Żmijewski, Artur. „Stosowane sztuki społeczne.” https://krytykapolityczna.pl/kultura/sztuki-wizualne/stosowane-sztuki-spoleczne/. Accessed September 2, 2024.

- Artur Żmijewski, „Stosowane sztuki społeczne” [Applied Social Arts], Krytyka Polityczna, https://krytykapolityczna.pl/kultura/sztuki-wizualne/stosowane-sztuki-spoleczne/ (accessed September 2, 2024). ↩︎

- Ibid., emphasis ours. ↩︎

- This approach was criticized by: Ewa Majewska, Sztuka jako pozór? Cenzura i inne paradoksy upolitycznienia kultury [Art as Appearance? Censorship and Other Paradoxes of the Politicization of Culture] (Kraków: Wydawnictwo Ha!art, 2013), 58–59; Michał Pospiszyl, “Sztuka instytucji mniejszych” [The Art of Minor Institutions], Dialog. Miesięcznik Poświęcony Dramaturgii Współczesnej, no. 11(732) (2017): 164. ↩︎

- See, for example, Kuba Szreder, „Pożegnanie z latami 90. W poszukiwaniu nowych formuł zaangażowania” [Farewell to the 1990s: In Search of New Formulas of Engagement], in Na okrągło: 1989–2009, ed. Jan Sowa and Andrzej Szyłak (Kraków–Wrocław: Korporacja Ha!art, BWA Wrocław, 2009); Rafał Jakubowicz, “Robotnicyzm. Sztuka w ujęciu radykalnym” [„Workerism: Art in a Radical Perspective”], in Wyparte dyskursy. Sztuka wobec zmian społecznych i dezindustrializacji lat 90. [Displaced Discourses: Art in the Face of Social Change and Deindustrialization of the 1990s], ed. Michał Iwański (Szczecin: Wydawnictwo Akademii Sztuki w Szczecinie, 2016). ↩︎

- The popularity of artistic uses of gender transgression is evidenced by the success of Łaźnia męska [Men’s Bathhouse] at the Venice Biennale, which, according to Sławomir Ratajski – then Secretary of State at the Ministry of Culture and Art – reflected, if not defined, global visual art trends. See „Teraz Kozyra? Polska performerka i jej promotorzy próbują epatować tanimi, przebrzmiałymi chwytami” [Now Kozyra? Polish Performer and Her Promoters Try to Shock with Cheap, Outdated Tricks], Życie, June 1, 1999. ↩︎

- Emma Heaney, The New Woman: Literary Modernism, Queer Theory and the Trans Feminine Allegory (Evanston: Northwestern University Press, 2017), 5. ↩︎

- On Żmijewski’s approach to disabled bodies, see Jakub Banasiak, „Historia nienaturalna. Na marginesie wystawy ‘Studium z natury i martwa natura’ Artura Żmijewskiego” [Unnatural History: On the Margins of Artur Żmijewski’s Exhibition „Study from Nature and Still Life’], Magazyn Szum, https://magazynszum.pl/historia-nienaturalna-na-marginesie-wystawy-studium-z-natury-i-martwa-natura-artura-zmijewskiego/ (accessed September 2, 2024). ↩︎

- Kay Gabriel, „Two Senses of Gender Abolition: Gender as Accumulation Strategy,” in Feminism Against Cisness, ed. Emma Heaney (Durham–London: Duke University Press, 2024), 136. ↩︎

- See Bożena Czubak in conversation with Alicja Żebrowska, in Negocjatorzy sztuki wobec rzeczywistości [Negotiators of Art in the Face of Reality], ed. Bożena Czubak (Gdańsk: Centrum Sztuki Współczesnej Łaźnia, 2000), 124. ↩︎

- Hartmut Böhme, „Podróż do wnętrza ciała i jeszcze dalej. Sztuka Alicji Żebrowskiej” [Journey Inside the Body and Beyond: The Art of Alicja Żebrowska], trans. Aleksandra Ubertowska, Magazyn Sztuki, no. 1–2 (1997). ↩︎

- Heaney, The New Woman, 10, emphasis ours. ↩︎

- Paweł Leszkowicz, „Po obu stronach lustra – w poszukiwaniu seksualności trzeciego tysiąclecia” [On Both Sides of the Mirror – In Search of Third Millennium Sexuality], in Onone. Świat po świecie [Onone. A World After the World] (Warsaw: CSW Zamek Ujazdowski, 1997), 1, emphasis ours. A similar approach appears in Izabela Kowalczyk’s interpretation of Łaźnia męska by Katarzyna Kozyra. She notes that gender „masquerade” is part of the avant-garde tradition, referencing Woolf’s Orlando or Man Ray’s photo of Duchamp as Rrose Sélavy. Kowalczyk appears to draw from both Leszkowicz and Böhme. See Izabela Kowalczyk, Ciało i władza. Sztuka krytyczna lat 90. [Body and Power: Polish Critical Art of the 1990s] (Warsaw: Wydawnictwo Sic! s.c., 2002), 175. It is worth noting that Duchamp’s photograph was inspired by Man Ray’s encounter with the trans feminine performer Barbette, photographed by him two years before photographing Duchamp in drag. ↩︎

- We use the term „transsexuality” as defined by Kay Gabriel, who frames it as a form of embodiment resulting from biomedical interventions or social signification involving gender transition – against both pathologizing medical definitions and increasingly disembodied narratives of trans experience. See Gabriel, „Two Senses of Gender Abolition,” 136. ↩︎

- Heaney, The New Woman, 29–39. The author of The New Woman reconstructs the history of discursive operations that transformed transfemininity into a literary figure, universalizing assumptions about gender, yet remaining constrained by the ideology of cisnormativity. She points out, among other things, how Sigmund Freud was the first to use the experience of transfemininity to theorize castration as a universal process of subject formation, and as a figure of an original state of human sexuality. This figure was later taken up by numerous modernist writers as a means of signaling shifts in the gender order and searching for truths about it. See also 5–8, 24, 39–48. ↩︎

- Allan Sekula, Społeczne użycia fotografii [Social Uses of Photography] (Warsaw: Wydawnictwo Uniwersytetu Warszawskiego; Zachęta Narodowa Galeria Sztuki, 2010), 46, 48–49. ↩︎

- Małgorzata Wyszyńska, „Zgorszenia nie będzie” [There Will Be No Scandal], Gazeta Wyborcza, https://classic.wyborcza.pl/archiwumGW/1080321/Zgorszenia-nie-bedzie (accessed September 2, 2024). ↩︎

- See Katarzyna Kozyra in conversation with Karol Radziszewski, „W czyim imieniu mówią dinozaury?” [On Whose Behalf Do Dinosaurs Speak?], in Być kimś, kim się (nie) jest [To Be Who One Is (Not)], ed. Pamela Bachar and Nina Hobgarska (Bielsko-Biała: Galeria Bielska BWA, 2025), 24–26. ↩︎

- Piotr Piotrowski, „Sztuka według polityki” [Art According to Politics], in Negocjatorzy sztuki, 29, emphasis ours. ↩︎

- On contemporary Marxist-feminist analyses of transition, see Transgender Marxism, ed. Jules Joanne Gleeson and Elle O’Rourke (London: Pluto Press, 2021); Bruno Monfort, „The Political Economy of Sexual Identity: From Gender Performativity to Social Reproduction,” Transgender Studies Quarterly 11, no. 2 (2024): 266–286. ↩︎

- Gabriel, “Two Senses of Gender Abolition,” 141–144. ↩︎

- Bożena Czubak, „Wobec rzeczywistości” [In the Face of Reality], in Negocjatorzy sztuki, 12. ↩︎

- Łukasz Gazur, „Eksplozja świetnej sztuki” [Explosion of Great Art], Gazeta Antykwaryczna Sztuka.pl, no. 1/2 (2006): 29. ↩︎

- Magda Szcześniak, Normy widzialności. Tożsamość w czasach transformacji [Norms of Visibility: Identity in Times of Transformation] (Warsaw: Fundacja Bęc Zmiana; Instytut Kultury Polskiej, 2016), 242–258. ↩︎

- Reina Gossett et al., „Known Unknowns: An Introduction to Trap Door,” in Trap Door: Trans Cultural Production and the Politics of Visibility, ed. Reina Gossett et al. (Boston: Massachusetts Institute of Technology, 2017), xv–xvi. ↩︎

- Łucja Iwanczewska, Potencjalności transformacji. Krótkie trwanie performansów kulturowych w Polsce lat 90. [Potentialities of Transformation: Short-Lived Cultural Performances in Poland of the 1990s] (Warsaw: Instytut Badań Literackich Polskiej Akademii Nauk, 2022), 23, 30. ↩︎

- Izabela Kowalczyk, „Wstęp” [Introduction], in Niebezpieczne związki sztuki z ciałem [Dangerous Relationships Between Art and the Body] (Poznań: Galeria Miejska Arsenał, 2002), 5. ↩︎

- Maria Dębińska, Transpłciowość w Polsce. Wytwarzanie kategorii [Transgenderism in Poland: Producing Categories] (Warsaw: Wydawnictwo Instytutu Archeologii i Etnologii PAN, 2020), 156. ↩︎

- See ibid., 106–125; Agnieszka Kościańska, Płeć, przyjemność, przemoc. Kształtowanie wiedzy eksperckiej o seksualności w Polsce [Gender, Pleasure, Violence: Shaping Expert Knowledge about Sexuality in Poland] (Warsaw: Wydawnictwo Uniwersytetu Warszawskiego, 2014); Ludmiła Janion, „ ‘Transsexuality’ and Gender Ratio in Poland: A Case Study on the East/West Dichotomy,” Journal of Homosexuality 70, no. 11 (2023). ↩︎

- Dębińska, Transpłciowość w Polsce, 175. ↩︎

- Ibid., 202. On the restrictiveness of reproduction politics in the post-socialist context, see Joanna Mishtal, The Politics of Morality: The Church, the State, and Reproductive Rights in Postsocialist Poland (Athens: Ohio University Press, 2015). ↩︎

- Ibid., 161. ↩︎

- Ewa Charkiewicz, “Ekonomia opieki i reforma systemu ochrony zdrowia” [Economics of Assistance and Health Care Reform], in Gender i ekonomia opieki [Gender and the Economics of Assistance], ed. Ewa Charkiewicz and Anna Zachorowska-Mazurkiewicz (Warsaw: Biblioteka Think Tanku Feministycznego, 2009), 128. ↩︎

- Dębińska, Transpłciowość w Polsce, 125. ↩︎

Łucja Staszkiewicz

A graduate of the Faculty of Artistic Research and Curatorial Studies at the Academy of Fine Arts in Warsaw and cultural studies at the University of Warsaw. She is a member of the zwykła dziewczyna [common girl] collective. She has co-curated projects such as Artistic, Social, Capital: Warsaw’s Artistic Studios as Micro-Institutions at the Warsaw Observatory of Culture, Bajzel w notatkach at Turnus Gallery, and Sztuka S-kraju at Pogłos. She participated in the conference Intimately Material: Violence, Social Reproduction, and Queerness in Transition at the European University Institute in Florence. Her texts and translations have been published in Machina Myśli and Dialog Puzyny.

Kacper Solecki

He is currently studying sociology and cultural studies at the University of Warsaw.