Title

Transformation of Energy, Expansion of Consciousness On the Origins, Assumptions, and Evolution of Marek Rogulski’s Artistic Concepts in the 1980s and 1990s

https://doi.org/10.48285/ASPWAW.29564158.MCE.2024.10.11EN

Marek Rogulski, Gdańsk, shamanism, New Age, esoteric studies, postmodernism

https://miejsce.asp.waw.pl/en/transformacja-energii-poszerzanie-swiadomosci/

Abstract

This article examines the key concepts, ideas, and recurring motifs in the work of Marek ”Rogulus” Rogulski, a Gdańsk-based artist who emerged in the mid-1980s and founded, among others, Fundacja Tysiąc Najjaśniejszych Słońc [The Thousand Brightest Suns Foundation] and the galleries C14~~~, Spichrz 7, and Spiż 7. Through an analysis of his actions, works of art, and theoretical writings, the article explores the central categories of energy and consciousness transformation, which Rogulski consistently investigated throughout the 1980s and 1990s. The primary interpretative frameworks include non-heterodox spiritual traditions (shamanism, New Age thought) as well as the anti-holistic premises of postmodern philosophy. Given the growing scholarly interest in positioning the art of the 1990s within the broader context of esotericism, this article argues for Rogulski’s artistic and theoretical practice as a crucial ele-ment in the reconfiguration of the artistic landscape during Poland’s transitional period.

Keywords

Marek Rogulski, Gdańsk, shamanism, New Age, esoteric studies, postmodernism

DOI

“In a sense, creative activity is a technique of transcendence.”1

“[…] art can be equated with life understood as a process of expanding consciousness.”2

As late as 1994, Krzysztof Jurecki observed that the paradigm shift in Polish art at the dawn of the 1990s was marked by “an exploration of new thematic preoccupations – astrology, shamanism, and magic conceived as genuine psychic realities – heralding the inexorable advent of the Age of Aquarius.”3 Although these remarks were originally included in a brief text concerning Marek “Rogulus” Rogulski (to whom this essay is also dedicated), they simultaneously alluded to a broader artistic current emerging at the time. This is hardly surprising, given that Jurecki would have had fresh recollections of exhibitions such as Magowie i mistycy [The Magicians and the Mystics] (CCA, Warsaw, 1991) and Perseweracja mistyczna i róża [Mystical Perseveration and the Rose] (PGS, Sopot, 1992), both of which foregrounded esoteric and mystical motifs. He may also have been familiar with discussions surrounding the exhibition Oto ciało moje, oto krew moja [Behold My Flesh, Behold My Blood], which was to subvert the biblical reference by imbuing it with rather heretical contents – at least from a Catholic perspective. Originally slated to take place at PGS in Sopot,4 it ultimately materialised under an altered guise – Antyciała [Antibodies] (CCA, Warsaw, 1995) – and is still considered one of the defining exhibitions of the decade. The change of title was more than a mere rhetorical recalibration – it signaled a fundamental reorientation of critical discourse, as spiritual inquiries were largely supplanted by corporeal and materialist concerns. Yet this does not mean that the specter of “heresy” was altogether absent from Antyciała. Likewise, the fact that the ascendant art criticism of the 1990s predominantly focused on gender, power dynamics, and corporeality did not necessarily preclude artists from engaging with heterodox spiritualities. Nevertheless, it is telling that these non-orthodox spiritual dimensions remained largely marginal within the dominant critical narratives of the 1990s. Only in recent years have these preoccupations been revisited and accorded critical attention.5

Since the new art emerging in Gdańsk in the 1990s – unlike, for instance, the dynamic milieu of Warsaw’s Kowalnia – was deeply rooted in the alternative cultural ferment of the preceding decade, it is worth recalling that mystical and esoteric currents had already begun to surface during that period.6 In Gdańsk, a fascination with unorthodox spiritualities clearly permeated artistic practice, although it took divergent paths, each marked by distinct strategies of conceptualising both social reality and the world as such. Broadly speaking, the creative attitudes that crystallised during this time may be delineated into two working categories. The first is predicated on the belief in the possibility of penetrating and revealing “mysterious” laws that govern the (omni)universe and finding a path towards their apprehension. By contrast, the second approach was informed by an acute awareness of the radical contingency of existence, which justifies its characterisation as catastrophic. The first approach is, in essence, optimistic: it posits the possibility of discerning a cosmic or divine order within which worldly chaos is either inconsequential or, ultimately, explicable through higher principles. The second, conversely, emerges from the conviction that chaos is the fundamental and immutable law governing existence. The former constitutes a kind of apologia for the Great Plan – be it cosmic or divine – offering those who subscribe to it a sense of meaning and participation in a supra-individual order. The latter, however, is imbued with an often radical pessimism, with its gnostic-existentialist tenor evoking the metaphor of the self as irrevocably thrown into the world.

Elsewhere,7 I have examined the catastrophic Gnostic motifs permeating the work of Grzegorz Klaman and Kazimierz Kowalczyk. Here, I would like to turn to the oeuvre and activities of Marek “Rogulus” Rogulski, whose artistic trajectory – though contemporaneous with Klaman and Kowalczyk, emerging in mid-1980s Gdańsk – derives from a fundamentally different, inherently optimistic conceptual framework. Highlighting this figure, supposedly “Poland’s longest-active artist engaged with shamanism”8 who has also been “suspected” of “occultism, alchemy, and other baroque transgressions,”9 is significant for at least two reasons. Firstly, his works and writings have yet to receive systematic scholarly treatment. This article, by delineating the key concepts, ideas, and motifs underpinning Rogulski’s artistic worldview and its manifestations, is intended as a contribution towards such an endeavour. Secondly, these “baroque transgressions,” which a Raster critic once noted with ironic detachment, appear no less symptomatic of Polish culture in the 1990s than the concerns of critical art, which is still regarded as synonymous with the period.

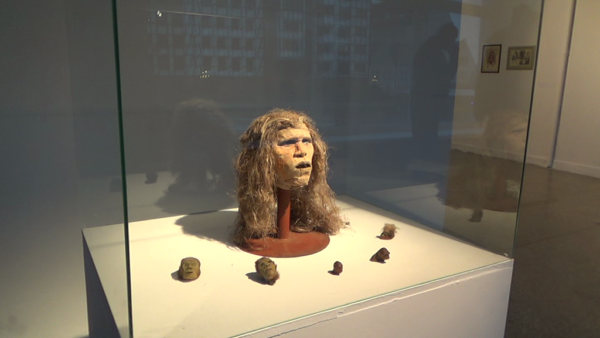

Rogulski’s artistic worldview and imagination were deeply shaped by his formative environment – specifically, his upbringing in a district of Gdańsk that borders the dense forests covering the moraine hills to the city’s south. His interest in prehistoric human cultures was further catalysed by a visit to London’s Natural History Museum, Jean-Jacques Annaud’s film Quest for Fire, and exposure to Western scientific literature brought back by his father from travels abroad.10 His other key influences also included Desmond Morris’s The Naked Ape and Adventures with the Missing Link by Raymond A. Dart and Dennis Craig. The impact of these encounters is already evident in Rogulski’s earliest sculptural works, produced during his high school years in 1984 – plaster blocks depicting the heads of prehistoric humans.

Marek Rogulski, models of hominid and archaic human heads, sculptures, 1983–1984, courtesy of Fundacja TNS

For Rogulski, the Oliwa woods were a sacred space – one in which he claims to have experienced a form of epiphany,11 communing with what he perceived as the primordial energy of nature. “I spent many moments with my head in the ground, inhaling the stench of earth and the stench of shit,”12 he remarked in 1991. Another formative experience etched in his memory was an open-air painting workshop in Chmielno in 1986, during which he would regularly retreat into the forest, immersing himself for hours in the swamp. These early excursions into the moraine landscape – his visceral engagement with what he imagined as nature’s “radiation” – may be seen as the genesis of the central tenet of his artistic worldview: the conviction that energy is the omnipresent force permeating all existence.

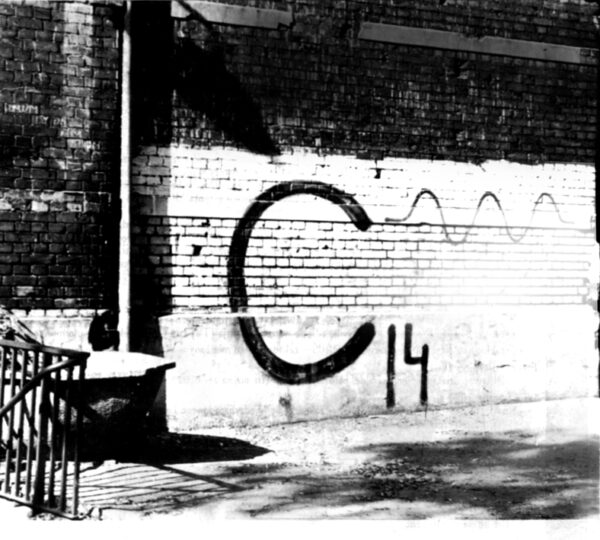

In 1991, Rogulski, together with Joanna Kabala and Andrzej Awsiej, established Galeria-Pracownia C14~~~ [C14~~~ Gallery-Workshop], housed within the Social Initiative Club – a space founded by members of alternative communities “for those who do not identify with the state, the Church, or big business.”13 The name of the gallery, which remained active only until June 1992, was a deliberate reference to the carbon isotope ¹⁴C, commonly used in geological and archaeological dating. This physicochemical method, which determines the age of organic materials based on the isotope’s decay under the influence of cosmic radiation, provided a fitting conceptual framework for the expansive vision of C14~~~‘s founders. Indeed, their imagination operated across vast temporal and spatial dimensions, reaching back to distant epochs while situating the cosmos and its permeating forces as the ultimate points of reference. This cosmological orientation is reflected in the gallery’s distinctive typography, immortalised on its exterior wall. The undulating “wave” (~) incorporated into its name, evoking vibration and oscillation, was conceived as “an expression of a certain frequency of energy, permeating everything, pervading the whole.”14 These very notions – energy and totality – lie at the core of Rogulski’s artistic philosophy and continue to serve as fundamental interpretative keys to his work.

Energy Omnitransformation

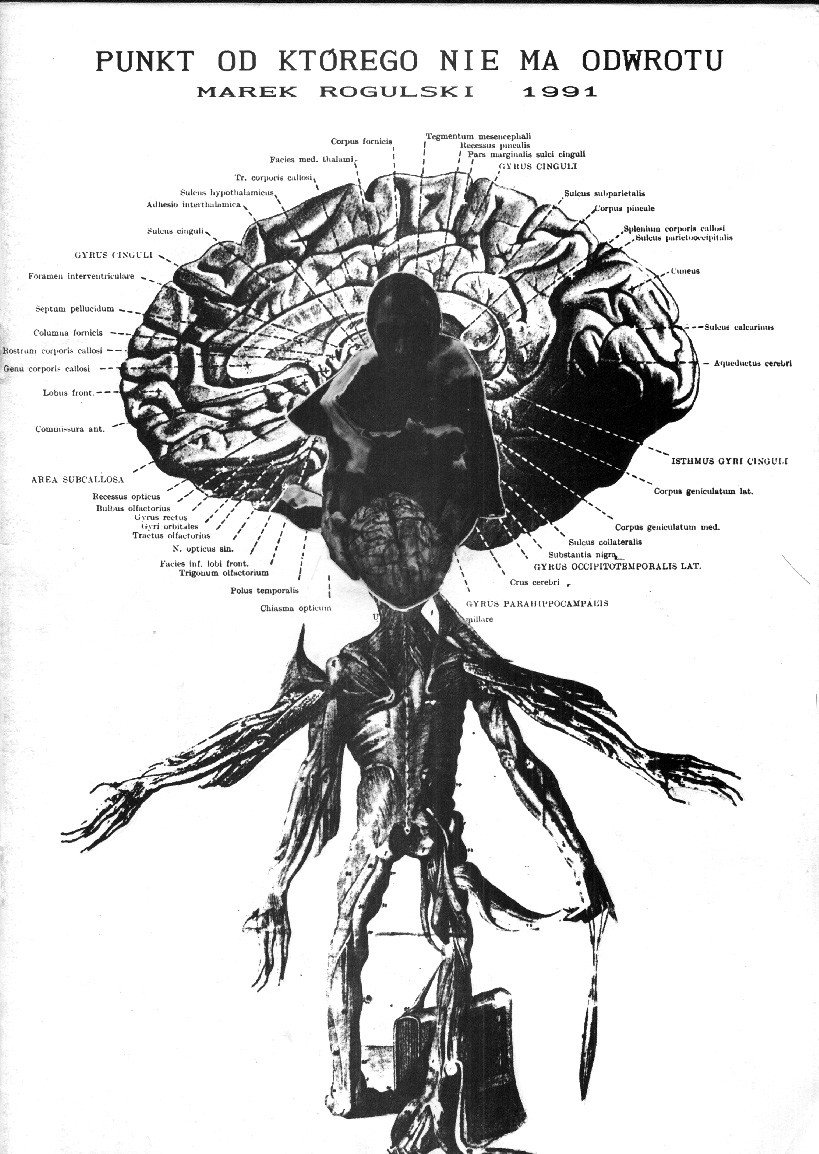

For Rogulski, the act of thinking about energy and feeling it was to result in a process of “pouring out” of specific objects and works.15 The phantasm of an all-pervasive energy not only defined his artistic practice but also provided a conceptual framework for determining the nature of art itself, one’s mode of engagement with history, and a model of interaction within social space. The theoretical foundations of this „energy philosophy” were articulated in Punkt od którego nie ma odwrotu [The Point of No Return], a self-published pamphlet from 1991, whose most extensive section, Mały traktat o transformowaniu energii [Small Treatise on Transforming Energy], outlined Rogulski’s core metaphysical propositions. Here, he posited that the world is suffused with a divine force – a “Potency of Existence” or “Energy Superpotency”16 – of which human beings are mere conduits. Yet, this “energetic existence” does not manifest solely on a singular plane; according to Rogulski,

[…] the diversity of our individual selves, despite our shared condition as mediums for the POTENCY OF EXISTENCE, renders us conduits for other, uniquely personal energies inherent to each of us. These energies span a vast spectrum – from the genetic material encoding the entire history of the Universe and evolution, to archetypal social behaviours, and finally, to deeply „private” energies imparted to us, not least, by the very cells of our parents. These and no others, in this precise place and time. Energies arriving from the cosmos at the moment of our birth, as well as those that define the spatial and temporal coordinates into which we emerge. Mental and spiritual energies.17

The artist’s interest was thus centred on the notion of “energy omnitransformation,”18 i.e. the interplay of diverse energy forms, their capacity for accumulation, and their role in structuring reality, which is made up of “manifestations of various types of energy.”19 For Rogulski, the world itself is

[…] a pulsating energy phenomenon of which we are a part, in which our existence – as individuated beings – as well as the events set into motion at specific, continuously unfolding spatio-temporal junctures, may be understood as the manifestation or revelation of particular energies.20

In his view, every human being is both a generator and a receptor of these energies, capable of emitting and absorbing them. Yet, the task of the artist is distinct: it is to transform and channel these energies into a work of art – or, more broadly, into an act of creation, which becomes “the embodiment of mental, intellectual, emotional, or other forms of energy within the structures of matter.”21

Rogulski’s reflections extend to the category of the viewer. If a work of art is “a peculiar integration, a fusion of the values inherent in the matter from which it is formed,” then, as he asserts, “the impulse of contact with it stimulates the viewer’s mind, which, in that moment, itself becomes a kind of matter co-creating the work.”22 What we encounter here is a distinctive equation: the work is the sum of energies perceived and materialised by the artist, combined with the artist’s own energy. Yet, for this energetic configuration to be fully realised, it requires a viewer endowed with the appropriate sensitivity – one capable of perceiving the energetic potential of the object and, through their resonance with it, contributing a fragment of their own energy to the total field. Thus, not everyone is capable of engaging with the work at its energetic level, and it is precisely in this condition that the esoteric dimension of Rogulski’s conception of art becomes most apparent.

The best examples of such “energy works” are the complex, multi-element installations Rogulski presented at Galeria C14~~~. Their intricacy positions them as counterbalances to the “primordiality” of his performances (to which I shall return later), yet both forms – alongside the entirety of his artistic practice – appear to stem from a shared imaginative nucleus. They articulate a fundamental drive: the desire to experience accumulated energy, whether as an „energy stream” coursing through the artist or as a sum of forces „emitted” by the installation’s constituent elements. Monumental in scale, composed of a multiplicity of elements – both minute and imposing, ephemeral and enduring – these installations manifest a movement of thought that seeks to integrate disparate dimensions of reality.

Among the elements Rogulski incorporated into his installations were objects symbolising “different levels of concentrated energy”23 – materials such as coal and aluminium, but also laboratory utensils, bones, animal skins, wood, and leaves. These were frequently combined with sound, neon light, or electricity. At times, the artist himself became an integral component of the installations, setting them in motion and engaging with them physically, transforming them into performance spaces. The multiplicity of elements within these works was structured according to Rogulski’s guiding principle: “Everything has […] a connection with everything else – it is enough to detect these connections.”24 This sentence accompanied the 1991 installation Stała grawitacji [Gravity Constant], exhibited at C14~~~. Other works from this period including Szybki ruch oczu [Rapid Eye Movement] (1992), Uwaga! Wysokie napięcie! Epoka progu – sama możliwość [Attention High Voltage! Threshold Epoch – Sheer Possibility] (1992), and Dzwon 100 GeV [Bell 100 GeV] (1992) – embody the same principle, though their formal compositions vary: some appear deliberately disordered, while others assume recognisable structures, such as bells or domes. Over time, the aesthetic character of these installations also evolved. Initially, they drew upon prehistoric imagery, incorporating skins and bones, yet they later transitioned into futuristic forms – vehicles, capsules, and other technological constructs. Nevertheless, their fundamental premise remained unchanged: the accumulation of energy and the pursuit of Wholeness. This intention was aptly articulated in what is likely the earliest commentary on Rogulski’s installations, penned by Andrzej Mestwin Fac, who wrote He wrote that “the structures and solids presented at the exhibition Stała grawitacji were […] an attempt to reveal the only accessible wholeness. The one that exists alongside us. Yet never beyond us.” And he added: “True, today we are surrounded primarily by fragments and particles. But after all, the binding element is the creator.”25

Marek Rogulski, Szybki ruch oczu [Rapid Eye Movement], installation, exhibition opening at Galeria C14~~~, 1992, courtesy of Fundacja TNS

From Shamanism to Esotericism

Rogulski steadfastly – perhaps even obsessively – pursues an artistic ethos understood as the cultivation of self-consciousness, a pursuit that necessitates the ceaseless motion of thought: grasping and articulating, only to then transcend and transmute itself. His artistic endeavour is predicated on the assimilation and transcendence of the successive stages of human consciousness, which he delineates as prehistoric, archaic/magical, mythical, modernist, and postmodernist. It is crucial to underscore that his objective is not abandonment but transcendence, for Rogulski’s imagination operates within a framework of continuity and metamorphosis, rather than rupture or reinvention. His vision is cumulative; to render this concept more graphically, one might liken his process to a system of interlinked vessels, into which successive elements are methodically introduced, rather than a mere cabinet of curiosities.

The manifestations of prehistoric consciousness that Rogulski explored in his early creative period are most distinctly discernible in the performances of the duo Ziemia Mindel Würm26 (1990–1993) – a collaboration with Piotr Wyrzykowski that drew upon shamanic practices. During the early 1990s, Rogulski engaged with an array of elements drawn from shamanic rituals: whips for self-flagellation, allusions to the mystical and shamanic experience of flight (levitation), fire as a symbol of purification, and various instruments – though notably not drums, which are commonly employed in animistic traditions – alongside recordings designed to induce a trance-like state. For Rogulski, however, shamanism, despite his profound fascination with it, remained a mediated spirituality. He recognised that it constituted a spiritual technique and praxis that was no longer directly accessible, its rhythm out of step with the accelerating momentum of late 20th-century civilisation. Nevertheless, his engagement with it did not descend into mere shamanic stylisation. Nevill Drury, a thinker associated with the Human Potential Movement – whose writings Rogulski himself referenced – observed that “shamanism is traditionally the religious expression of a nomadic era of hunter-gatherers,” and “it would surely be partaking of a fantasy to endeavour to transpose the world of the shaman to our own contemporary setting in any literal way.”27 However, Drury also identified aspects of the shamanic experience that offer potential emancipation from the constraints of technocratic modernity. The first is the sense of communion with a deeper spiritual reality, which enables a rejection of any “formal religious frameworks or belief system based on some form of empty, inherited doctrine.” The second is the holistic perception of reality as an interwoven, animate cosmos, a universe pulsing with energy, vibration, and rhythm.28

Rogulski and Wyrzykowski must have been propelled by a similar intuition when realising Ziemia Mindel Würm’s performances. The tension between the primordiality of Nature and the disarray of technocratic civilisation finds a powerful echo in Wyrzykowski’s anti-urbanist text from 1992, in which he observes:

Urban space – a complex, jittery mass, impossible to grasp in its entirety through the senses. It overwhelms the mind or compels a narrowing of perception. The eye absorbs only fragments, incapable of assembling them into a coherent whole. The sheer excess of recorded impressions, the chaos of information, engenders unease, fear, uncertainty. Man seeks silence, order – he longs for the stark austerity of raw fields, of forests.29

Given this critical stance towards civilisation, it is hardly surprising that the artists chose the aforementioned moraine hills of the Oliwa forests as the site for many of their performances. In 1990, Jan “Yach” Paszkiewicz documented an action by Ziemia Mindel Würm and produced am accompanying music video. The footage features quintessential elements of the duo’s performances – self-flagellation, quasi-ritualistic markings inscribed upon their half-naked bodies – yet, tailored to the format of a music video, it does not fully capture the trance-like, rhythmic intensity that characterised Ziemia Mindel Würm’s live actions, particularly those on Spichrzowa Island in Gdańsk. This elemental rhythm finds its most visceral expression in the action CH3NHCH2 – nieustające adrenalino spady [CH₃NHCH₂ – Incessant Adrenaline Falls], which was structured around a skeletal framework of white-painted branches, resembling a hut

Marek Rogulski, CH₃NHCH₂ – nieustające adrenalinospady [CH₃NHCH₂ – Incessant Adrenaline Falls], performance of Ziemia Mindel Würm, Galeria Wyspa, 1990, courtesy of Fundacja TNS

At its centre, the artists suspended a metal plate, inscribed with a spiral motif. Within this structure, Wyrzykowski, clad in a white shirt, his legs bound in a sack, writhed upon the ground in worm-like, crawling motions. Meanwhile, Rogulski, wearing cow hide trousers, his bare torso covered in white paint and intersecting black lines, encircled the construction, lashing himself to the point of drawing blood. The cadence of his movements was dictated by a soundtrack reverberating from loudspeakers, imbuing the entire action with an astral choreography, intended to mirror the movement of celestial bodies.

The title of another performance, Naczynie Transmutacji [The Vessel of Transmutation], already signals a transition in Rogulski’s artistic trajectory – one increasingly inspired by his engagement with the occult, esotericism, and the symbolic traditions of secret societies such as Freemasonry and Rosicrucianism, as well as alchemy and Hermeticism. In this action, Wyrzykowski stood naked against the wall of the granary, assuming the pose of crucifixion, while Rogulski touched his body with meat roasted during the performance. It is telling that when Adam Jurecki, in a 1997 interview, inquired whether Rogulski considered himself a shaman, the artist responded:

These days, I prefer to describe myself as a member of the Secret Order. […] Shamanism, as a starting point for our conversation, is appropriate. But I would like to steer us toward certain worldview systems that humanity has cultivated within itself – systems such as Tantric techniques, and in the West, Rosicrucian philosophy or Kabbalah. It is about the path of inner development, of ascending to higher realms and then acting within them.30

The artist’s intensified engagement with Eastern and Western esoteric traditions emerged after the dissolution of Ziemia Mindel Würm and reached its peak between 1995 and 1999. This period coincided with Rogulski’s founding of the Spichrz 7 Gallery on Spichrz Island – a space that, in 1997, was relocated and renamed Spiż 7 – as well as the inception of his Poza postmodernizm [Beyond Postmodernism] project. At Spiż and Spichrz, Rogulski curated a number of group exhibitions whose very titles alluded to esoteric and hermetic themes, including Tajny Zakon [Secret Order] (1995), Fantom Hermeticum [Phantom Hermeticum] (1995), Hoc est secretis focus (1995), and Sfera Homunculus [Homunculus Sphere] (1996)

This phase of Rogulski’s artistic development was defined by “a vision of occult progression striving for omnipotence and omniscience.31

To Transcend Postmodernism

The prehistoric, magical, mistical, and modernist forms of consciousness that preoccupied Rogulski were rather holistic in nature – as the artist saw them, they offered coherent narratives about the world. The prehistoric phase of consciousness was guided by sexuality and emotions, the archaic by magic and symbols, followed by myths, and in modernity, by the idea of an emancipated subject, continuous progress, and development.32 Postmodernism, with its “self-reflexive,” decentralised, and contextual thinking, posed a different challenge, one against which Rogulski was ultimately compelled to take a stance. On one hand, he acknowledged aspects of postmodernism that resonated with his own creative philosophy. For instance, he remarked that “postmodernism has opened us up to the whole complexity of the world,”33 that its significance lay “in the discovery […] that worldviews evolve,”34 that “there are different versions of the same story,”35 and that “the world is largely the result of our interpretation.”36 On the other hand, the postmodern pluralism of attitudes and perspectives, despite its attractiveness, presented a more elusive terrain than prehistoric, mythical, or even modernist forms. Postmodernism dismantled the myth of the Whole, rejecting grand narratives in favour of an interplay of quotations and fragments, embracing aporia and the logic of cultural recycling.

The “high level of self-consciousness”37 that Rogulski discerned in postmodern culture and art, along with their “assimilability and recognisability only to those individuals who have acquired the cognitive categories of previous degrees of consciousness,”38 only superficially aligns with his artistic concepts. The fundamental divergence lies in the fact that, for Rogulski, the expansion of consciousness is a cumulative and expansive process, one that sustains the hope of uninterrupted development. In essence, it is a ceaseless flight forward, a continuous act of transcendence understood as the perpetual transgression of the consciousness status quo. This is why the postmodern assertion that “none of the structures we have discovered is final, unquestionable, […] because any meta-language can become a language for another meta-language,”39 aligns with Rogulski’s vision only to a limited extent. Postmodernism maintains that the meta-linguistic realm is inescapable – it is a constitutive framework for an ever-evolving system of language. In contrast, Rogulski contends – an argument to which he subordinates his entire artistic practice – that postmodern consciousness is not the ultimate truth about the world, but rather a phase that can be transcended and integrated into a larger Whole. In this sense, the postmodern worldview resembles a closed labyrinth, in which consciousness expands only to encounter the same elements of the cultural imaginarium – images, fragments, quotations – albeit through ever-shifting pathways. By contrast, consciousness in Rogulski’s work, though still searching for its own meta-sphere, follows a trajectory that is, so to speak, linear – or rather, ascending. His artistic concepts bear a resemblance to the mystical path, where the elaboration of ideas and the creation of objects and actions serve as a means of spiritual refinement.

The paradox lies in the fact that the New Age rhetoric resonant in Rogulski’s texts emerges from the very core of postmodern sensibility. While the holistic ideas promising to embrace the Whole – so central to New Age thought – might seem at odds with postmodernism, understood as an apologia for fragmentation and quotation, postmodernism itself did not position itself in opposition to such ideas. On the contrary, its foundation in plurality and the coexistence of divergent worldviews necessitated the inclusion of perspectives that contradicted its own anti-holistic inclinations. Thus, the conviction in the human mind’s capacity to “harmonise the self with the world into a new unity” and to cultivate a “cosmic consciousness, ‘co-sensing the universe as an expanded body and the self as a concentrated consciousness of earth, nature, and the cosmos’”40 emerged as one of postmodernism’s most emblematic tendencies.

Rogulski did not distance himself from the New Age, yet he remained critically discerning of its intellectual pitfalls and limitations. In one interview, he remarked: “Unfortunately, very valuable elements – the fruits of sometimes thousands of years of spiritual practice from many traditions – have been indiscriminately thrown into one vast repository, alongside a whole spectrum of absurd, naïve theories.”41 Rather than embracing the New Age indiscriminately, Rogulski selected and drew inspiration from those currents that aligned with what Bartłomiej Dobroczyński termed the High New Era – a body of thought grounded in scientific paradigms, characterised by a “high intellectual calibre and considerable self-awareness.”42 Rogulski read, referenced in catalogues, and engaged with the ideas of thinkers associated with this „high” New Age, such as Ken Wilber, Nevill Drury, and Stanislav Grof – figures concerned with consciousness in its development, expansion, transcendence, and access to transmental and transpersonal realms. Rogulski valued only those New Age propositions that framed humanity, nature, and the cosmos as an interconnected Whole. Conversely, he criticised the New Age movement as a heterogeneous amalgam of contradictory concepts, lacking intellectual rigour. In particular, he objected to its failure to “distinguish between irrational and transrational experiences.”43

It was within the realm of the trans that Rogulski discerned a remedy for the “peculiar cultural exhaustion”44 of postmodernism and its restrictive rationalist disposition. He viewed postmodern artists as figures who “exploit above all intellectual potential,” thereby “denying themselves the chance for an inner transformation of consciousness.”45 In response, he argued that

the postmodern existentialist must finally realise that there is a level of transpersonal perception whose perception can and must be developed […]. This task concerns shifting the point of one’s own identity no longer only from the body to the mind, as in modernism, but from the mind to the whole Cosmos with all aspects of its manifestation.46

To achieve it, “the individual subject […] must be able to deny the truth which is the foundation of his worldview and which, at this level of consciousness, actually fulfils its purpose.”47 In other words – it was necessary to one transcend the current form of consciousness. It is unsurprising, then, that Rogulski found inspiration in transpersonal psychology.48 One of its most notable advocates, the aforementioned Nevill Drury, asserted that this kind of awakening of consciousness “is very much an adventure of self-transformation which eventually takes us beyond self itself. It is a journey towards wholeness, towards totality of being.”49

Rogulski outlined the methods of liberation from the constraints of postmodern consciousness in his text Podstawy manifestu współczesnej kontrkultury [Fundamentals of the Manifesto of Contemporary Counterculture] (2000–2001), where he continued the inquiries initiated in Punkt od którego nie ma odwrotu [The Point of No Return].

By that time, his focus had shifted away from the question of energies permeating the universe towards the transcendence of consciousness paradigms. What is most striking, however, is that in this second text, Rogulski articulated a revised conception of the work of art itself. While in Punkt od którego nie ma odwrotu, he argued that the work of art primarily manifests as a cumulative form of energy, in Podstawy manifestu…, he offered a more process-oriented perspective:

The „work” here is the very process of transforming consciousness, including the collective consciousness, and not just some concrete work, an artistic work, the making of an object or the creation of some situation. A process that […] will one day lead to a clear and self-conscious unity of Spirit […] in a transmental, transpersonal and transrational Superconsciousness.50

The multifaceted and long-term project Poza postmodernism, initiated by Rogulski in 1999, was conceived as an attempt to surpass the postmodern paradigm of consciousness. He pursued this vision through actions, objects, exhibitions, and theoretical texts, in which he articulated its underlying principles. Podstawy manifestu współczesnej kontrkultury and Poza postmodernizm – uchwycić siłę… [Beyond Postmodernism – To Capture the Power…], both published in Explorer, a magazine edited by the artist, stand as its most representative expressions.51 During this period, Rogulski depicted the transcendence of consciousness through evocative metaphors. He often incorporated explosives into his works – an allusion to the possibility of a sudden ignition of awareness, an explosive illumination.

Marek Rogulski, Ani podmiot ani przedmiot – obiekt bomba [Neither Subject nor Object – Bomb Object], installation, Galeria Spiż 7, 2000, courtesy of Fundacja TNS

The integration of body and mind, in turn, was central to works such as Poza ciało, poza umysł [Beyond Body, Beyond Mind]. As a critic from Gazeta Morska noted, mind and body “are to become only a tool […] leading to their transcendence and the achievement of a state of ‘transmental’, supra-individual consciousness.“52 At other times, Rogulski would confine himself within spherical constructions, only to escape from them during performances – a gesture meant to symbolise transcendence, the rejection of constraints, and the liberation from the limits of consciousness.

Conclusions

Krzysztof Jurecki, mentioned at the outset of this discussion, anticipated the esoteric turn in the art of the 1990s and identified Rogulski as one of the pioneering figures in this field. He observed that the artist “does not engage in political moralising and art with political overtones. He is interested in philosophical issues, interpreted on the basis of astrology, concerning the essence of our lives.”53 Contrary to Jurecki’s intuition, however, the 1990s have largely been remembered and historicised as an era dominated by politically charged critical art. This remains the prevailing narrative, even though many of the artists associated with this critical paradigm simultaneously explored mystical and esoteric themes. One finds, for instance, Gnostic motifs independently emerging in the work of Grzegorz Klaman54 and Zbigniew Libera,55 an engagement with Christian mysticism among graduates of Grzegorz Kowalski’s studio,56 Paweł Althamer’s psychedelic fascinations,57 and the work of Alicja Żebrowska, which has recently been reinterpreted through the lens of new spirituality in Tajemnica patrzy (The Mystery Is Looking, Gdańska Galeria Miejska, 2024), an exhibition curated by Jakub Banasiak.

Rogulski has never been identified with critical art. While he did not dismiss its legitimacy, he regarded it as merely one of many possible ways of describing reality – a mode of thought that, like others, had to be understood, assimilated, and ultimately transcended. That said, the programmatic conflict that arose between him and Grzegorz Klaman in 1994 may have reinforced his aversion to the rhetoric of “politicization” and “criticality,” which in Gdańsk found institutional strongholds in spaces such as Wyspa Gallery and Łaźnia CCA. As Zofia Tomczyk-Watrak succinctly observed,

If Grzegorz Klaman’s idea of his art and tactics was to move from underground spaces to public spaces and, consequently, to institutions, Marek Rogulski, on the contrary, combined artistic creation with internal, mental space.58

It is telling that, at the very moment when critical art discourse was crystallising in Poland, Rogulski was founding yet another of his ephemeral institutions – the Centre for the Study of Inner Space. His deliberate withdrawal from the dominant critical paradigm, coupled with his inward-oriented artistic exploration, placed him on the margins of mainstream art criticism. His absence from the indexes of books on Polish art of the 1990s is indicative of this critical blind spot.

However, the recent scholarly attention to esoteric currents in the art and culture of this decade has provided an alternative interpretative lens – one that not only recasts critical art in a new light but also allows for a juxtaposition with the work of artists previously excluded from this framework. This shift may lead to a re-evaluation of transformation art, the development of a different critical vocabulary, and a reconfiguration of established artistic hierarchies. It appears increasingly evident that Marek Rogulski is one of those artists without whom the “esoteric history of Polish art in the 1990s”59 cannot be fully told.

Translated by Karol Waniek

Bibliography

“Ani piekło, ani niebo. Tylko Logos.” Interview by Krzysztof Jurecki with Marek Rogulski. Exit, no. 1 (1997).

Bromboszcz, Rafał. “Poszerzanie światopoglądu. Geneza projektu Poza Postmodernizm.” Interview with Marek Rogulski. In Zwiadowca. Projekt Poza Postmodernizm [re: re: rekonstrukcja], edited by Marek Rogulski. Gdańsk: CSW Łaźnia, 2009.

“Bródnowska nirwana.” Interview by Artur Żmijewski with Paweł Althamer. Czereja, no. 3 (1993).

Dobroczyński, Bartłomiej. New Age. Kraków: Znak, 1997.

Drenda, Olga. Duchologia polska. Rzeczy i ludzie w latach transformacji. Kraków: Karakter, 2016.

Drury, Nevill. The Elements of Human Potential. Shaftesbury, Dorset: Element Books, 1989.

Drury, Nevill. The Elements of Shamanism. Shaftesbury, Dorset: Element Books, 1989.

Dziamski, Grzegorz. “Co po nowoczesności?” In Postmodernizm. Teksty polskich autorów, edited by Maria Anna Potocka, 257–276. Kraków: Bunkier Sztuki, Inter Esse, 2003.

[Fac], A. M. “O instalacjach Marka Rogulskiego słów kilka.” Przedproża, nos. 14–15 (1991).

Hall, David. New Age w Polsce. Lokalny wymiar globalnego zjawiska. Warsaw: Wydawnictwa Akademickie i Profesjonalne, 2007.

Jurecki, Krzysztof. “Dzikie moce Lucyfera – w twórczości Marka Rogulskiego.” In Konzeption PL. Zeitgenössische Kunst aus Nordpolen, edited by Z. Pacholski and M. Rehkopp. Rheine: Kulturforum Rheine, 1994.

Jurecki, Krzysztof. “Szaman – miłośnik życia, znajomy śmierci.” Kalejdoskop, no. 10 (1996).

Jurecki, Krzysztof. Kwestia szamanizmu we współczesnej sztuce polskiej na przykładzie Marka Rogulskiego. In Marek Rogulski. Aerolit – zaplatanie energii. Toruń: Galeria Sztuki Wozownia, 2015.

Jurecki, Krzysztof. Marek Rogulski “Rogulus”. In Re/prezentacja. Drogi artystyczne absolwentów gdańskiej ASP, edited by Łukasz Guzek. Gdańsk: ASP w Gdańsku, 2015.

“Kalendarium. Galeria C14.” Przedproża, nos. 14–15 (1991).

“Klub Inicjatyw Społecznych C14~.” In 3 dni C14~~~. 31. V – 2. VI 1991, Gdańsk: Wydawnictwo Kubańskie Cycki, 1991.

Kopańska, Marta. “Nowe energie. Twórczość Ewy Ciepielewskiej w perspektywie New Age.” Szum, no. 37 (2022).

Kozioł, Wojciech. “Kosmici, czyli my. Filozofia Nowej Ery jako trop interpretacyjny twórczości Pawła Althamera, ze szczególnym uwzględnieniem koncepcji Carla Gustava Junga.” Miejsce, no. 3 (2017).

Kozioł, Wojciech. “Wystawa w Laboratorium Centrum Sztuki Współczesnej w 1992 roku, czyli gnostycyzm w twórczości Zbigniewa Libery.” Elementy, no. 2 (2022).

Księżyk, Rafał. Śnialnia. Śląski underground. Kraków: Wydawnictwo Literackie, 2023.

“Lekcja anatomii.” Interview by Mikołaj Wroniszewski with Marek Rogulski. Gazeta GUMed, no. 1 (2024). Accessed May 1, 2024. https://gazeta.gumed.edu.pl/attachment/attachment/97437/Gazeta_GUMed_2024_styczen.pdf.

Łukowski, Tomasz and Marek Rogulski (eds.) TNS. Gdańsk: Wydawnictwo Szszsz, Fundacja Tysiąc Najjaśniejszych Słońc, 1999.

Możdżyński, Piotr. Inicjacje i transgresje. Antystrukturalność sztuki XX i XXI wieku w oczach socjologa. Warsaw: Wydawnictwa Uniwersytetu Warszawskiego, 2011.

“O C-14 z Markiem Rogulskim rozmawia Danuta Godycka.” Obieg, nos. 4–5 (1992).

Rogulski, Marek, ed. Marek Rogulski. Hiperbola – bańki, chmury, modele, fantomy. Sopot: PGS w Sopocie, 2015.

Rogulski, Marek. Podstawy manifestu współczesnej kontrkultury. Gdańsk: Wydawnictwo Szszsz, Fundacja TNS, Galeria Spiż 7, 2000–2001.

Rogulski, Marek. Poza Postmodernizm. Sopot: PGS w Sopocie, 2001.

Rogulski, Marek. Punkt od którego nie ma odwrotu. Gdańsk: Wydawnictwo Szszsz, 1991.

“Rogulus Rogulski, Poza Postmodernizm – uchwycić siłę…” Explorer, no. 4 (2004).

“Rozmowa A. Drewy z A. Awsiejem i M. Rogulskim.” Metafizyka Społeczna, no. 1 (1992).

Sobolewska, Agnieszka. Mapy duchowe współczesności. Co nam zostało z Nowej Ery? Warsaw: W.A.B., 2009.

Stanisławski, K. “Nie męcz ptaka.” Art Newsletter Sopot, nos. 4/5/6 (1995).

Stańczyk, Xawery. Macie swoją kulturę. Kultura alternatywna w Polsce 1978–1996. Warsaw: Narodowe Centrum Kultury, 2018.

Śmigłowicz, Paweł. „Układ scalony sztuki polskiej.” In Raster. Macie swoich krytyków. Antologia tekstów, edited by Jakub Banasiak, 143–157. Warsaw: Stowarzyszenie 40 000 Malarzy, 2009.

Tomczyk-Watrak, Zofia. Wybory i przemilczenia. Od szkoły sopockiej do nowej szkoły gdańskiej. Gdańsk: Słowo / obraz, 2001.

“W latach 90. liczył się monolit.” Interview by Mikołaj Wroniszewski with Marek Rogulski. Szum, no. 13 (2023). Accessed May 1, 2024. https://magazynszum.pl/w-latach-90-liczyl-sie-monolit-rozmowa-z-markiem-rogulusem-rogulskim.

“Wilgotna Litania. Aneks do orędzia Jacka Markiewicza.” Edited by K. Tuflin. Czereja, no. 4 (1993).

Wisłocki, Sławomir. “Nowa świadomość.” Gazeta Morska, supplement to Gazeta Wyborcza, April 26, 2000.

Wroniszewski, Mikołaj. Gnostycka podszewka. O sztuce Grzegorza Klamana i Kazimierza Kowalczyka. In Sztuka transformacji. Wątki gdańskie, edited by A. Grzonkowska and M. Wroniszewski. Gdańsk: Fundacja Kultury Wizualnej Chmura, 2024 (forthcoming).

Wyrzykowski, Piotr. “Potrzebna nam jest transfuzja krwi.” Przedproża, nos. 14–15 (1991).

“Wyspa a Nekropolis – czytanie warstw.” Conversation with R. Rumas, M. Rogulski, J. Spica, G. Klaman, and E. Banecka. Przedproża, no. 11 (1991).

“Zintegrować i przekroczyć postmodernizm.” Interview by Agnieszka Wojewoda with Marek Rogulski. Obieg, May 14, 2010. Accessed May 1, 2024. https://archiwum-obieg.u-jazdowski.pl/rozmowy/17246.

Żmijewski, Artur. “Białe małżeństwo.” Czereja, no. 4 (1993).

- Marek Rogulski, Galeria Spichrz 7 – Spiż 7 Fundacji Tysiąc Najjaśniejszych Słońc. Transformacyjny charakter galerii i ezoteryczne źródła idei [Spichrz 7 Gallery – Spiż 7 of the Tysiąc Najjaśniejszych Słońc Foundation. The Transformational Nature of the Gallery and the Esoteric Sources of the Idea], in TNS, ed. T. Łukowski and M. Rogulski (Gdańsk: Wydawnictwo Szszsz, Fundacja Tysiąc Najjaśniejszych Słońc, 1999), 46. ↩︎

- Marek Rogulski (Rogulus), “Ani piekło, ani niebo. Tylko Logos” [Neither Hell nor Heaven. Only Logos] [interview by K. Jurecki], in Krzysztof Jurecki, Poszukiwanie sensu fotografii. Rozmowy o sztuce [Searching for the Meaning of Photography. Conversations on Art] (Toruń: Galeria Sztuki Wozownia, 2008), 121–22. ↩︎

- Krzysztof Jurecki, “Dzikie moce Lucyfera – w twórczości Marka Rogulskiego” [The Wild Powers of Lucifer – in the Work of Marek Rogulski], in Konzeption PL. Zeitgenössische Kunst aus Nordpolen, ed. Z. Pacholski and M. Rehkopp (Rheine: Kulturforum Rheine, 1994), n.p. ↩︎

- See K. Stanisławski, “Nie męcz ptaka” [Don’t Torment the Bird], Art Newsletter Sopot 1995, no. 4/5/6: 23. ↩︎

- See, e.g., P. Możdżyński, Inicjacje i transgresje. Antystrukturalność sztuki XX i XXI wieku w oczach socjologa [Initiations and Transgressions. The Anti-Structural Nature of 20th and 21st-Century Art in the Eyes of a Sociologist] (Warsaw: Wydawnictwa Uniwersytetu Warszawskiego, 2011); W. Kozioł, “Kosmici, czyli my. Filozofia Nowej Ery jako trop interpretacyjny twórczości Pawła Althamera, ze szczególnym uwzględnieniem koncepcji Carla Gustava Junga” [Aliens, That Is, Us. The Philosophy of the New Age as an Interpretative Approach to the Work of Paweł Althamer, with Particular Emphasis on Carl Gustav Jung’s Concept], Miejsce 2017, no. 3; eadem, “Wystawa w Laboratorium Centrum Sztuki Współczesnej w 1992 roku, czyli gnostycyzm w twórczości Zbigniewa Libery” [The 1992 Exhibition in the Laboratory of the Contemporary Art Center, or Gnosticism in the Work of Zbigniew Libera], Elementy 2022, no. 2; M. Kopańska, “Nowe energie. Twórczość Ewy Ciepielewskiej w perspektywie New Age” [New Energies. The Work of Ewa Ciepielewska in the Perspective of the New Age], Szum 2022, no. 37. ↩︎

- X. Stańczyk, Macie swoją kulturę. Kultura alternatywna w Polsce 1978–1996 [You Have Your Own Culture. Alternative Culture in Poland 1978–1996] (Warsaw: Narodowe Centrum Kultury, 2018), 15, 118, 143–46. See also O. Drenda, Duchologia polska. Rzeczy i ludzie w latach transformacji [Polish Hauntology. Things and People in the Years of Transformation] (Kraków: Karakter, 2016), 195–214. ↩︎

- M. Wroniszewski, “Gnostycka podszewka. O sztuce Grzegorza Klamana i Kazimierza Kowalczyka” [The Gnostic Underside. On the Art of Grzegorz Klaman and Kazimierz Kowalczyk], in Sztuka transformacji. Wątki gdańskie [The Art of Transformation. Gdańsk Themes], ed. A. Grzonkowska and M. Wroniszewski (Gdańsk: Fundacja Kultury Wizualnej Chmura, 2024) [forthcoming]. ↩︎

- Krzysztof Jurecki, “Kwestia szamanizmu we współczesnej sztuce polskiej na przykładzie Marka Rogulskiego” [The Issue of Shamanism in Contemporary Polish Art on the Example of Marek Rogulski], in Marek Rogulski. Aerolit – zaplatanie energii [Aerolite – Weaving Energy] (Toruń: Galeria Sztuki Wozownia, 2015), 8. See also idem, “Szaman – miłośnik życia, znajomy śmierci” [Shaman – A Lover of Life, A Friend of Death], Kalejdoskop 1996, no. 10: 41. ↩︎

- P. Śmigłowicz, “Układ scalony sztuki polskiej” [The Integrated Circuit of Polish Art], in Raster. Macie swoich krytyków. Antologia tekstów [Raster. You Have Your Own Critics. An Anthology of Texts], ed. J. Banasiak (Warsaw: Stowarzyszenie 40 000 Malarzy, 2009), 74. ↩︎

- “Lekcja anatomii” [Anatomy Lesson] [interview by M. Wroniszewski with M. Rogulski], Gazeta GUMed 2024, no. 1: 70, https://gazeta.gumed.edu.pl/attachment/attachment/97437/Gazeta_GUMed_2024_styczen.pdf (accessed on 1 May 2024). ↩︎

- “W latach 90. liczył się monolit. Rozmowa z Markiem ‘Rogulusem’ Rogulskim” [In the 90s, the Monolith Mattered. A Conversation with Marek ”Rogulus” Rogulski] [interview by M. Wroniszewski], Szum 2023, no. 13, https://magazynszum.pl/w-latach-90-liczyl-sie-monolit-rozmowa-z-markiem-rogulusem-rogulskim/ (accessed on 1 May 2024). ↩︎

- “Wyspa a Nekropolis – czytanie warstw” [The Island and Nekropolis – Reading the Layers] [conversation with R. Rumas, M. Rogulski, J. Spica, G. Klaman, and E. Banecka], Przedproża 1991, no. 11: 8. ↩︎

- Klub Inicjatyw Społecznych C14~ [Club of Social Initiatives C14~], in 3 dni C14~~~. 31. V – 2. VI 1991 [3 Days of C14~~~. 31 May 31 – 2 June 1991] (Gdańsk: Wydawnictwo Kubańskie Cycki, [1991]), n.p. ↩︎

- [Interview by A. Drewa with A. Awsiej and M. Rogulski], Metafizyka Społeczna [Social Metaphysics] 1992, no. 1: 4. ↩︎

- “O C-14 z Markiem Rogulskim rozmawia Danuta Godycka” [Danuta Godycka Talks to Marek Rogulski about C-14], Obieg 1992, no. 4–5: 57. ↩︎

- Marek Rogulski, Punkt od którego nie ma odwrotu [The Point of No Return] (Gdańsk: Wydawnictwo Szszsz, [1991]), n.p. ↩︎

- Ibid. ↩︎

- Ibid. ↩︎

- Ibid. ↩︎

- Ibid. ↩︎

- Ibid. ↩︎

- Ibid. ↩︎

- “Galeria C 14. Kalendarium 1991–1999” [C14 Gallery. Chronology 1991–1999], in TNS, op. cit., 27. ↩︎

- “Kalendarium. Galeria C14” [Chronology. C14 Gallery], Przedproża 1991, no. 14–15: 2. ↩︎

- A. Mestwin [Fac], “O instalacjach Marka Rogulskiego słów kilka” [A Few Words About Marek Rogulski’s Installations], Przedproża 1991, no. 14–15: 14. ↩︎

- „This name, like in the case of C14~~~, is significant. Mindel and Würm are the names of glaciations that occurred in Europe during the Pleistocene epoch.” ↩︎

- Drury, Nevill. The Elements of Shamanism. Shaftesbury, Dorset: Element Books, 1989, pp. 99-100. ↩︎

- Ibid., p. 101. ↩︎

- P. Wyrzykowski, “Potrzebna nam jest transfuzja krwi” [We Need a Blood Transfusion], Przedproża 1991, no. 14–15: 19. ↩︎

- “Ani piekło, ani niebo. Tylko Logos” [Neither Hell nor Heaven. Only Logos] [interview by K. Jurecki with M. Rogulski], Exit 1997, no. 1: 1390. ↩︎

- Ibid, p. 1388. ↩︎

- Marek Rogulski, “Hiperbola” [Hyperbola], in Marek Rogulski. Hiperbola – bańki, chmury, modele, fantomy [Hyperbola – Bubbles, Clouds, Models, Phantoms], ed. M. Rogulski (Sopot: PGS w Sopocie, [2015]), 22. ↩︎

- Marek Rogulski “Rogulus” [interview by Ł. Guzek], in Re/prezentacja. Drogi artystyczne absolwentów gdańskiej ASP [Re/Presentation. Artistic Paths of Graduates of the Academy of Fine Arts in Gdańsk], ed. Ł. Guzek (Gdańsk: ASP w Gdańsku, 2015), 60.. ↩︎

- Marek Rogulski, Poza Postmodernizm – komentarz odautorski [Beyond Postmodernism – The Author’s Commentary], in TNS, op. cit., 130. ↩︎

- Idem, Podstawy manifestu współczesnej kontrkultury [Foundations of the Contemporary Counterculture Manifesto] (Gdańsk: Wydawnictwo Szszsz…, Fundacja TNS, Galeria Spiż 7, 2000–2001), 3. ↩︎

- “Poszerzanie światopoglądu. Geneza projektu Poza Postmodernizm” [Expanding Worldview. The Genesis of the Beyond Postmodernism Project] [interview by R. Bromboszcz with M. Rogulski], in Zwiadowca. Projekt Poza Postmodernizm [re: re: rekonstrukcja] [Scout. The Beyond Postmodernism Project [re: re: reconstruction]], ed. M. Rogulski (Gdańsk: CSW Łaźnia, [2009]), 126. ↩︎

- Marek Rogulski, Hiperbola…, op. cit., 39. ↩︎

- Idem, Podstawy manifestu współczesnej kontrkultury…, op. cit., 3. ↩︎

- G. Dziamski, “Co po nowoczesności?” [What Comes After Modernity?], in Postmodernizm. Teksty polskich autorów [Postmodernism. Texts by Polish Authors], ed. M. A. Potocka (Kraków: Bunkier Sztuki, inter esse, 2003), 33. ↩︎

- Ibid, p. 28. Dziamski refers to and cites the findings and works of Jean Gebser and Ihab Hassan (I. Hassan, Ideas of Cultural Change, in Innovation/Renovation. New Perspectives in the Humanities, eds. I. Hassan and S. Hassan [Wisconsin, 1983], 29). It should be noted that, like postmodernism, the New Age itself has been interpreter – depending on the interpretative position –both as an example of the formation of a metanarrative and as an instance of intellectual non-conclusiveness and fluidity. See D. Hall, New Age w Polsce. Lokalny wymiar globalnego zjawiska [The New Age in Poland. The Local Dimension of a Global Phenomenon] (Warsaw: Wydawnictwa Akademickie i Profesjonalne, 2007), 74. ↩︎

- “Zintegrować i przekroczyć postmodernizm. Rozmowa z Markiem Rogulskim” [To Integrate and Surpass Postmodernism. A Conversation with Marek Rogulski] [interview by A. Wojewoda], Obieg, May 14, 2010, https://archiwum-obieg.u-jazdowski.pl/rozmowy/17246 (accessed May 1, 2024). ↩︎

- B. Dobroczyński, New Age (Kraków: Znak, 1997), 94. The The author contrasts the High New Age with the commercial Low New Age, also referred to as the Occult New Age, that is, ”undertakings aimed rather at mass reception and characterised essentially by a market or commercial perspective” (ibid., 92). In this ”parapsychological-magical-occult spectrum,” Dobroczyński writes, various elements coexist side by side, for example, ”‘miraculous’ crystals, magical talismans and amulets, various types of horoscopes and divination techniques […], more or less naïve – possibly charlatan – healing and psychotherapeutic techniques, practices for improving the mind and increasing efficiency” (ibid., 92). ↩︎

- Zintegrować i przekroczyć postmodernizm…, op. cit. ↩︎

- Marek Rogulski, Hiperbola…, op. cit., 39. ↩︎

- Idem, “Poza Postmodernizm – uchwycić siłę…” [Beyond Postmodernism – Capturing the Force], Explorer 2004, no. 4: 7. ↩︎

- Idem, Podstawy manifestu współczesnej kontrkultury…, op. cit., 6. ↩︎

- Ibid, 5. ↩︎

- It is not the place here to delve deeply into the validity of the concept of transpersonal psychology. However, to illustrate its discursive ambiguity, it is worth noting that Dobroczyński, an experienced scholar of both new religious movements and the history of psychology, on the one hand, includes authors associated with this trend among the pioneers of the High New Age (see note 41), while elsewhere he situates transpersonal psychology within the realm of “unofficial medicine and exotic therapeutic movements,” such as “Chinese medicine, herbalism, homeopathy, […] the ‘Human Potential Movement’ ”—B. Dobroczyński, Już po Nowej Erze [After the New Age], Tygodnik Powszechny 2003, no. 8; cited in A. Sobolewska, Mapy duchowe współczesności. Co nam zostało z Nowej Ery? [Spiritual Maps of Modernity. What Remains of the New Age?] (Warsaw: W.A.B., 2009), 17. ↩︎

- Drury, Nevill. The Elements of Human Potential. Shaftesbury, Dorset: Element Books, 1989, 13. ↩︎

- Marek Rogulski (Rogulus), Podstawy manifestu współczesnej kontrkultury…, op. cit., 12. ↩︎

- See also, among others, M. Rogulus Rogulski, Nowy paradygmat: doświadczenie pozaczasowego, doświadczenie nieskończoności [The New Paradigm: The Experience of the Timeless, the Experience of Infinity], in Marek Rogulus Rogulski. Poza Postmodernizm [Beyond Postmodernism] (Sopot: PGS w Sopocie, [2001]). ↩︎

- S. Wisłocki, “Nowa świadomość” [New Consciousness], Gazeta Morska, supplement to Gazeta Wyborcza, April 26, 2000. ↩︎

- Krzysztof Jurecki, Dzikie moce Lucyfera…, op. cit. ↩︎

- See Mikołaj Wroniszewski, Gnostycka podszewka…, op. cit. ↩︎

- See Wojciech Kozioł, Wystawa w Laboratorium Centrum Sztuki Współczesnej w 1992 roku…, op. cit. ↩︎

- A. Żmijewski, “Białe małżeństwo” [White Marriage], Czereja 1993, no. 4; “Wilgotna Litania. Aneks do orędzia Jacka Markiewicza” [The Moist Litany. An Annex to Jacek Markiewicz’s Message], selected and edited by K. Tuflin, Czereja 1993, no. 4. ↩︎

- See Bródnowska nirwana [Bródno Nirvana] [interview by A. Żmijewski with P. Althamer], Czereja 1993, no. 3.; Wojciech Kozioł, Kosmici, czyli we…, op. cit. ↩︎

- Z. Tomczyk-Watrak, Choices and silences. Od szkoły sopocka do nowej szkoły gdańskiej, słowo / obraz, Gdańsk 2001, p. 161 ↩︎

- This reference pertains to Rafał Księżyk’s book Śnialnia. Śląski underground [The Dream Room. Silesian Underground] (Kraków: Wydawnictwo Literackie, 2023), which was advertised as an “esoteric history of Polish intelligentsia.” Thanks to Księżyk, we now have an idea of how such a narrative about the 1990s might be imagined. ↩︎

Maksymilian Wroniszewski

Is a writer, editor, and scholar specializing in literature, art, and theatre. His work has been featured in cultural and academic journals, including Kultura Współczesna, Ruch Literacki, Sztuka i Dokumentacja, Dialog, Teatr, Didaskalia, Odra, Orońsko, and Szum. He has co-authored and co-edited several books and exhibition catalogues, including Grzegorz Klaman. Polonia (with Klaudia Renusch, PGS Sopot, 2016), Kino według Marii Janion (with Paweł Biliński, Klub Żak, 2016), and Re: Iredyński (with Zbigniew Majchrowski, IBL PAN, 2018). His current research focuses primarily on the art scene in Gdańsk during the 1980s and 1990s.