Title

Art and Entrepreneurship Jacek Markiewicz’s a.r.t. Gallery as a Field of Speculation

https://doi.org/10.48285/ASPWAW.29564158.MCE.2024.10.6EN

Jacek Markiewicz; galeria a.r.t.; transformacja ustrojowa; spekulacja; neoliberalizm; podmiot przedsiębiorczy; autonomia sztuki; krytyka infrastrukturalna

https://miejsce.asp.waw.pl/en/sztuka-i-przedsiebiorczosc/

Abstract

The article examines the operation of Jacek Markiewicz’s a.r.t. gallery within the framework of the socio-economic transformation of the 1990s, highlighting the key tensions between art, labor, and the capitalist logic of speculation. The gallery, run as an independent artistic initiative and financed through the artist’s business activities, served as a nexus of individual entrepreneurship and the attempt to preserve artistic autonomy. Drawing on Marina Vishmidt’s theory of speculation, the article explores how the gallery engaged with neoliberal processes of redefining the artist’s role and the field of art. It addresses issues related to artistic infrastructure and the conflict between local and global contexts of artistic practice. Central to the analysis is the figure of the ”entrepreneurial subject,” oscillating between critique and integration into the capitalist system. The article reveals how artistic autonomy in 1990s Poland was intrinsically tied to market logic, which redefined the concepts of labor and art, while also exposing the limitations of art’s emancipatory potential under the conditions of systemic transformation.

Keywords

Jacek Markiewicz; galeria a.r.t.; transformacja ustrojowa; spekulacja; neoliberalizm; podmiot przedsiębiorczy; autonomia sztuki; krytyka infrastrukturalna

DOI

The Conditions of Possibility of Art at the Time of Transformation

Jacek Markiewicz attended Prof. Grzegorz Kowalski’s studio at the Faculty of Sculpture at the Academy of Fine Arts in Warsaw from 1989 to 1993, when he completed his diploma project, Adoracja [Adoration]. Although he remained artistically active for several years, he largely withdrew from the art scene around the turn of the millennium.1 His practice still warrants thorough analysis, and his institutional activities remain even less examined. Despite the significance of the a.r.t. gallery, which he ran in Płock and which became a key site on Poland’s artistic map in the 1990s, its operations have never been the subject of in-depth study. Meanwhile, it was precisely within this space that the defining tensions of the transformation era emerged – between neoliberal ideals and economic realities on the one hand, and between the pursuit of artistic autonomy and the constraints of a small-town context on the other.

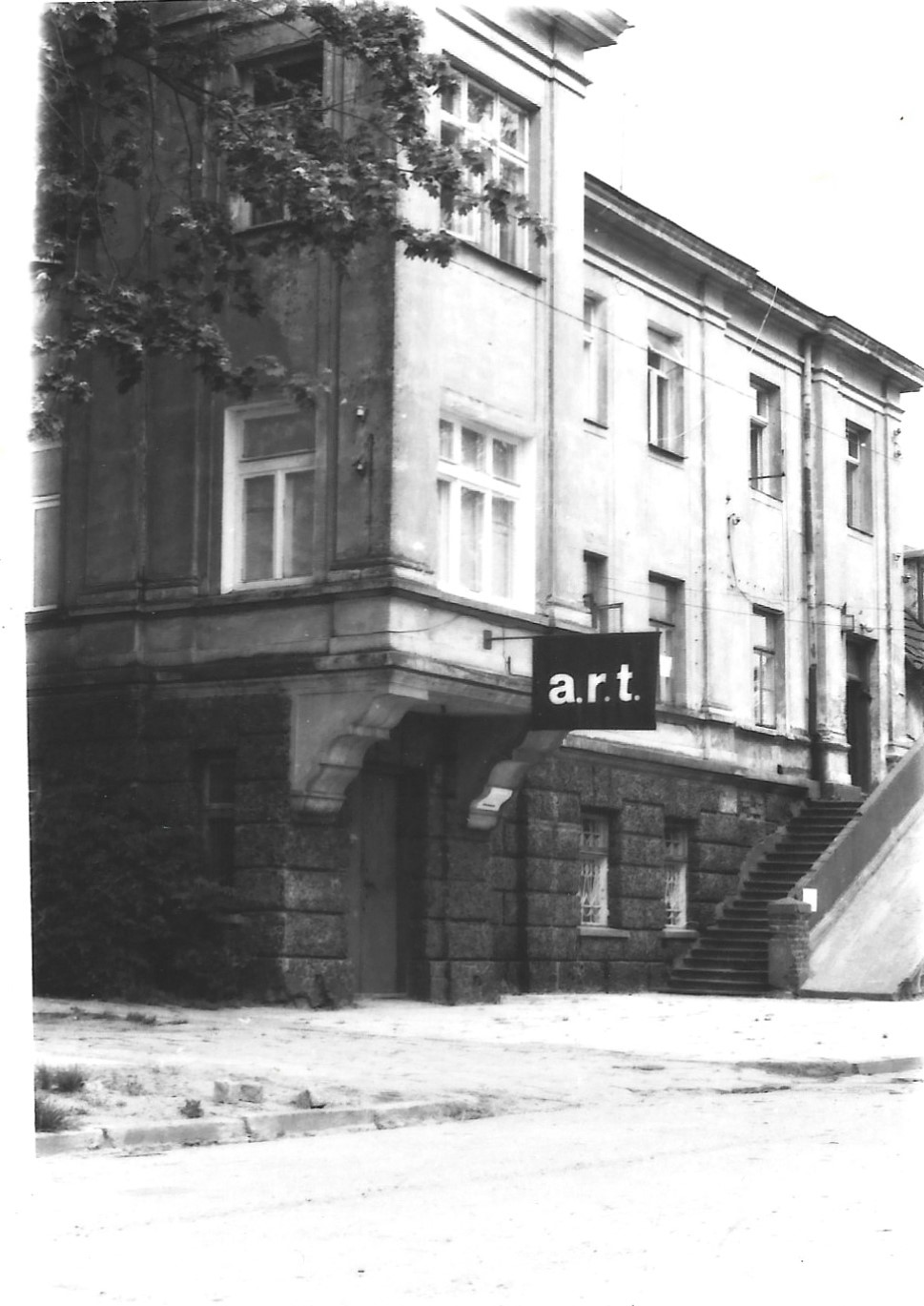

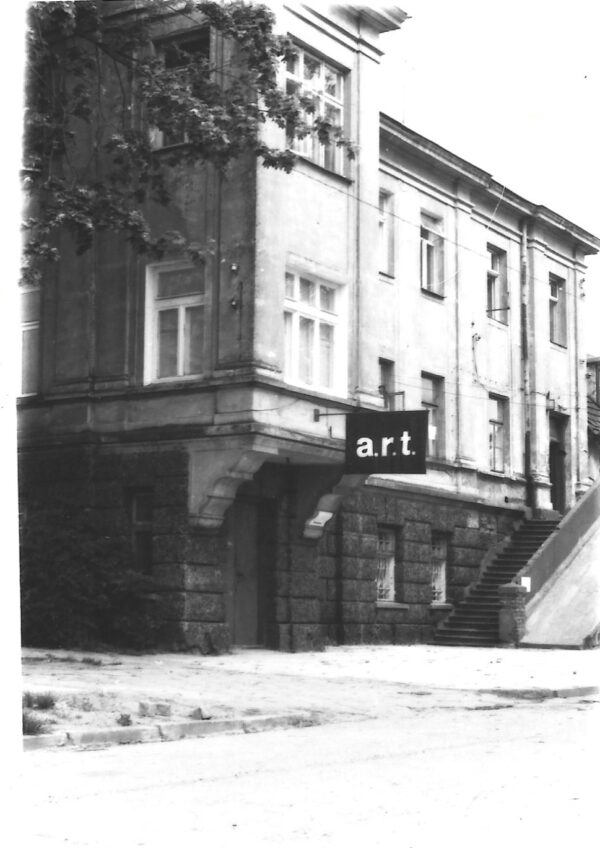

Founded in 1992, the a.r.t. gallery was initially located on the first floor of a tenement house at ul. Rybaki 7 in Płock, overlooking the Vistula River. A year later, Markiewicz rented the Water Tower at ul. Warszawska 26 from the city, which allowed the gallery to function in two parallel locations – one on the outskirts and another in the center. In the 2000s, it relocated to Rogatki Dobrzyńskie, where it functioned until its closure in 2010. The gallery’s program focused on solo exhibitions, primarily showcasing artists affiliated with Prof. Kowalski’s studio – ”Kowalnia” – such as Katarzyna Kozyra, Paweł Althamer, or Artur Żmijewski. Rather than imposing a curatorial framework, Markiewicz gave artists full autonomy in selecting their themes.

Although the gallery functioned until 2010, it was most active between 1992 and 1997, and this period is the focus of this analysis.2 A crucial backdrop for examining the relationship between the capitalist appropriation of labor, life, and time and the operation of an independent art institution is provided by critical analyses of the transformation era in culture and art, as explored by scholars such as Magdalena Szcześniak, Łukasz Zaremba, Jakub Banasiak, Andrzej Szczerski, and Wiktoria Kozioł.3 From the outset, Markiewicz emphasized that the gallery functioned solely thanks to the funds from his private wholesale business, positioning the intersection of labor, business, and art as the foundation of both autonomy and creative freedom. In his vision, art was to remain independent of public institutions and insulated from economic pressures. However, I argue that from its inception, the gallery was embedded within mechanisms of speculative valorization – not as a market commodity, but as a site for the production of symbolic value, which, over time, contributed to its institutional recognition. Here, speculation serves as a crucial lens for analyzing transformative processes, revealing how art became entangled in capitalist structures of valuation.

In my research on the a.r.t. gallery, I draw on what Marina Vishmidt describes as the ”conditions of possibility” of a given artistic phenomenon.4 These conditions shape the framework that defines what can be recognized as art at a specific time and place, as well as what kinds of activities can be incorporated into this realm – even when they emerge beyond its traditional boundaries. Simultaneously, these conditions allow practitioners operating within the art world to exert influence beyond it, shaping other disciplines and social contexts. Thus, my focus is on the intricate network of factors that constitute the infrastructure of artistic practice.

According to Vishmidt, contemporary conditions of possibility – particularly in the late phase of capitalism – are primarily shaped by speculative thinking. She defines speculation as a fundamental mechanism of contemporary relations between art, capital, and subjectivity, intertwining the logic of financialization with creative processes.5 Both art and capital rely on randomness, the fluidity of time, and experimentation with the creation – and capitalization – of possible worlds. Understood in this way, art becomes an integral component of neoliberal logic while simultaneously existing in dialectical tension with it. By exposing this relationship, Vishmidt also critiques the ideology of artistic autonomy, traditionally defined as art’s independence from labor and capitalism.6 She argues that the notion of artistic freedom and creative autonomy serves as a form of camouflage – one that not only obscures the structural dependence of the art world on capital but also actively constructs a particular kind of artistic subject. This subject’s visions of the future are constrained by speculative relations with the market, where every creative act is inscribed within the broader logic of capitalist accumulation.

In this context, the Polish transformation of the 1990s can be understood as a moment when speculation and the pursuit of artistic autonomy became deeply intertwined, reshaping both the role of the artist and the function of art within the emerging economic order. The transitological logic imposed at the time – centered on the transition to liberal democracy and neoliberal capitalism – necessitated a redefinition of subjectivity as well as the entire cultural and artistic landscape. The transformation was not merely an economic shift but also a cultural project, in which ”justified risk” became the dominant organizing principle of social life.7 This involved economic risk, as state support for the arts was dismantled and artists were forced to show individual entrepreneurship, but also artistic risk, which demanded a rethinking of artistic autonomy and value within a neoliberal market. These systemic changes required artists to become what Pierre Dardot and Christian Laval describe as the entrepreneurial subject8 – an individual constantly investing in their own resources, including creativity, flexibility, and productivity, in order to navigate and sustain themselves within the new socio-economic conditions.

I interpret Markiewicz’s activity within the framework of the a.r.t. gallery as a speculative field where the tensions outlined above converge. In Płock during the 1990s, specific conditions of possibility emerged that shaped a distinct relationship between art and the market – one that differed from Western models, despite the artist’s adoption of the neoliberal role of the entrepreneurial subject. Here, economic dependence and artistic freedom were inextricably linked: Markiewicz not only programmatically emphasized the connection between his warehouse and the gallery but also frequently referenced his business in his artistic practice. However, the very obviousness and normality of this relationship – as an implicit guarantor of creative freedom – ultimately restricted the artist’s autonomy. Under the conditions of possibility at the time of transformation, artistic production became inseparable from the neoliberal art infrastructure, foreclosing alternative modes of creation. In this article, my focus is not on how Markiewicz thematized his relationship with business – an aspect already explored by Karol Sienkiewicz and Wiktoria Kozioł – but rather on how his a.r.t. gallery reproduced the conditions of possibility for a new artistic infrastructure during the period of transformation.9

A Speculative Journey to Freedom

In 1989, Markiewicz spent a year and a half in the United States – an experience that proved crucial in shaping both his artistic practice and his gallery activities. He traveled overseas after winning the sculpture category of the 1988 Art Horizon – New York competition, though, as he later reflected, the award primarily served as a justification for securing a visa.10 The trip was financed through borrowed funds, and once in the USA, he took on employment that not only covered his travel expenses but also allowed him to save money – resources that later enabled him to establish his business in Poland. In this sense, the journey itself functioned as a speculative act, emblematic of the risk-taking and investment in future possibilities characteristic of economic migration during the transformation period. However, I am particularly interested in how this journey shaped the artist’s subjectivity, aligning it with the logic of neoliberalism.

In a 1993 interview with Marek Grała, Markiewicz recalled the experience: ”It worked out, I got the prize. I started dreaming about the USA. One of the painters living in Płock at the time, Wiesław Pawlak, had returned from there and told me about the exhibitions he had seen.”11 In a separate conversation with Lena Szatkowska, the artist emphasized the openness of both art and its reception in the West: ”They have a different approach to all phenomena in contemporary art.”12 Reflecting on his time abroad, he remarked: ”[…] it was a very important experience and certainly had a big impact on me and my work. I went to exhibitions, I learned, I traveled, I wanted to see as much as possible. After returning from there, my work underwent radical changes.”13 For Markiewicz, the search for new artistic forms – closely tied to his understanding of freedom, both artistic and personal – was inherently linked to the Western art system. Equally important were the independent trips he organized with fellow students to exhibitions in Kassel, Aachen, and Basel.14 As he notes, these experiences exposed him to works shaped by an economic and technological reality that remained largely inaccessible in Poland at the time.

These recollections diminish the direct influence of Grzegorz Kowalski’s pedagogical program on Markiewicz’s artistic practice while reinforcing the formative role of exposure to Western art.15 It is as if the artist inscribed himself in the transitological logic, in which post-communist societies were perceived as underdeveloped and in need of training for freedom. Boris Buden stresses that such narratives of transformation naturalized liberal democracy and neoliberal capitalism as the only conceivable path of development.16 The teleological notion of ”catching up with the West” suggested that achieving ”normality” merely required the replication of solutions already established in the so-called civilizational center.

Meanwhile, the solutions implemented in the United States reflected a specific entanglement of art and capital. Vishmidt, in her research on speculation, describes it as both a method of inquiry and an inherent contradiction within the contemporary relationship between artistic and economic spheres. At the same time, she distinguishes between two fundamental dimensions of speculation: open and closed. Open speculation refers to the emancipatory potential of art – its capacity to generate new forms of life and modes of existence beyond market logic. It represents a space of experimentation and possibility, where artistic practices can engage in the critical transformation of reality.17 For Vishmidt, the crucial challenge is to reclaim this emancipatory potential. However, it remains contingent on closed speculation, which operates within capitalist valorization mechanisms, focusing on the production of value through the continuous reproduction of existing structures and the subordination of the future to present power and capital relations.18

This paradoxical dependence stresses the fundamental contradiction of contemporary art. In the case of closed speculation, the symbolic value of art becomes embedded in market logic – whether through the production of high-value market objects or the self-valorization of creativity as a functional component of the capitalist system. Vishmidt highlights that by the 1990s, particularly in the United States, the artistic infrastructure had become fully subordinated to market imperatives.19 While art institutions had long operated under a hybrid business model – one adapted to the American cultural system, which minimizes government support in favor of private market funding – the unique status of art became increasingly entangled with the neoliberal cultural industry. The artist remained honored as a creator, yet was simultaneously absorbed into a system of exchangeable value, where soft skills such as creativity and flexibility were as prized as traditional forms of capital. This particular fusion of art’s exceptional status with its submission to market forces deeply shaped the notions of artistic freedom that Markiewicz brought back to Poland during the political transformation.

The a.r.t. Gallery and the Infrastructure of Transformation

The concept of infrastructure, previously mentioned, is central to Vishmidt’s theoretical framework. She deliberately shifts the focus from artistic institutions to infrastructure in order to reveal the broader network of interdependencies that entangle art. In her view, infrastructure encompasses both the physical – galleries, institutions – and the immaterial – cultural norms, value systems, political and economic structures, and labor relations.20 Infrastructure, therefore, is not merely a fixed object but a relation – a dynamic process that organizes resources, space, and social actors. Crucially, art does not simply rely on existing infrastructure; it actively shapes and transforms it, both materially (e.g., exhibition spaces) and symbolically (e.g., through the values ascribed to artworks). By examining the conditions of possibility produced through these processes, Vishmidt advances an infrastructural critique that moves beyond discourse analysis to recognize the material foundations of art as inextricable from the capitalist system.

Infrastructural critique needs to take into account historical and local contexts in order to analyze the varying strategies through which art institutions are integrated into economic structures. The a.r.t. gallery emerged at a moment when Polish cultural institutions were still in the process of redefining themselves. In 1990, significant personnel shifts took place at the Ujazdowski Castle Centre for Contemporary Art, the network of the Bureaus of Art Exhibitions (BWA) was reorganized into city galleries – some of which began showing new artistic phenomena – and Zachęta, formerly the Central Bureau of Art Exhibitions, underwent radical transformation. Meanwhile, galleries affiliated with the Academies of Fine Arts still existed but no longer held the prominence they had in the 1980s. At the same time, as Jakub Banasiak writes, neoliberal logic led to infrastructural collapse and the pauperization of artists.21 For Markiewicz, however, this situation did not present an opportunity for open speculation – the creation of alternative artistic structures distinct from Western models or the communal reorganization of infrastructure. The teleological trajectory of transformation left no room for such emancipatory potential. Submission to market forces became the sole viable path for sustaining creative work: only those who could best adapt to the new economic conditions would survive.

Against this backdrop, the a.r.t. gallery in Płock emerges as a unique case. It was a fully independent, privately run space, unconnected to the restructuring of state institutions in the wake of transformation and entirely free from public funding. Yet, despite its private nature, it was not profit-driven – Markiewicz did not intend to engage in the commercial trade of works of art. In this sense, it functioned more like a private foundation, though without a distinct legal status. Instead, its role in supporting artistic performances was simply integrated into the artist’s broader economic activities in retail and wholesale. For Markiewicz, the gallery’s defining principle was independence from municipal authorities.22 He deliberately avoided collaboration with public cultural institutions and had no interest in managing the Bureau of Art Exhibitions in Płock. The artist still associates involvement with the public sector with bureaucratic censorship that prevents full artistic autonomy.

Markiewicz’s explicit rejection of collaboration with municipal institutions and public funding in interviews from the 1990s aligns seamlessly with the logic of neoliberal individuality. The independence he kept emphasizing – both artistic and organizational – embodied a model in which the artist assumes full responsibility for their own actions, simultaneously becoming the manager, sponsor, and curator of their practice. Their privately funded activity reinforced the notion of art as a distinct and autonomous sphere, free from external influence and obligation – art as a self-contained field in which the artist functions as a ”subject of judgment.”23 As Vishmidt observes, this concept assigns the artist a privileged role as an arbiter of aesthetic and moral values – an idea further reinforced within neoliberalism by the myth of self-sufficiency and the singularity of artistic subjectivity. By rejecting public support and distancing himself from city institutions, Markiewicz subscribed to a model in which art remains a pure, self-regulating domain and the artist – an independent entity, ostensibly detached from the surrounding economic and institutional structures.

It is important to note that the logic of transformation also compelled city authorities to integrate the public sector into the evolving artistic infrastructure. In several instances, the municipality provided support for Markiewicz’s activities, funding, among other things, the publication and promotion of the a.r.t. 1992–1997 catalog. However, these were sporadic, ad hoc interventions rather than part of a systemic mechanism of supporting the arts. An indirect consequence of this approach was the reinforcement of a model in which artists were expected to function as self-entrepreneurs. Moreover, discussions about cultural funding in Płock in 1992 took place within the broader context of deep budget cuts. Municipal authorities argued that in a ”normal reality,” culture should sustain itself financially. Yet the then-director of the Dramatic Theatre, Marek Mokrowiecki stated: ”We are told that culture in the world finances itself, but the truth is that it is subsidized everywhere.”24 The Dramatic Theatre of Płock, together with the Regional Council of Local Government, initiated the Organizing Committee of the Foundation for the Defense of Culture (FOK). Interestingly, rather than exerting pressure on public authorities, this initiative sought to establish a framework for cooperation between business and culture, promoting a model in which artistic activities in the city could be sustained through private capital.25 Markiewicz, however, chose not to engage in these efforts, relying entirely on his private business ventures.

The separation of Markiewicz’s gallery from the city’s infrastructure was reinforced by its initial location at ul. Rybaki 7. Consequently, the a.r.t. gallery – at least in the perception of some – functioned as an autarkic entity, detached from the social fabric of its surroundings. The deteriorating infrastructure of the tenement houses in this part of Płock significantly contributed to declining living conditions, leading to the socio-economic marginalization of the area. As this process unfolded, the district became increasingly associated with lower-income residents, rising tensions, and a surge in petty crime. Children spent much of their time on the streets, while some residents used the existing resources, such as fishing in the Vistula. The gallery itself was therefore literally on the city’s periphery – housed in a building where the ground floor was abandoned, and the upper floors contained a few residential apartments. The structure bore no resemblance to a prestigious art space; its only visual marker was a flag displayed in the window. This spatial and symbolic marginalization contributed to the limited engagement of local residents with the gallery’s programming. While the artist attempted to bridge this gap, he did so from a judgmental point of view, which automatically distanced him from the city’s more conservative social circles.

The first seat of the a.r.t. gallery at Rybaki 7 street in Płock, 1992, from the private archive of Jacek Markiewicz

Interviews and reviews from the 1990s suggest that Markiewicz hoped for support from the local art community, yet cooperation never materialized. He emphasized his gallery’s role as ”the first contact that the inhabitants of Płock have with contemporary art. I care about young people. I go to schools and distribute invitations.„26 At the same time, the gallery maintained strong ties with the Warsaw art scene, particularly with artists from ”Kowalnia,” who visited regularly: ”Most of the visitors are still from Warsaw. This unusual place on the Vistula is widely talked about in the capital and attracts both artists and critics, who attend every exhibition. It turns out that only Płock lacks the appropriate interest.”27 In the cultural center, neoliberal scripts surrounding artistic autonomy are always more readily absorbed.

Markiewicz’s aspiration to cultivate an audience for contemporary art in Płock ultimately collided with the structural limitations of a peripheral city – one that lacked the artistic infrastructure necessary to foster dialogue between the remnants of the previous system’s institutions and emerging private initiatives. In 2008, he expressed his frustration: ”In Warsaw, crowds of people come to see contemporary art exhibitions […] Here, only young people who are not afraid to cross the threshold of a gallery come. We are a society of Tayger and ‘Manhattan’.”28 In the same interview, he described the Płock audience as dormant. Such statements reveal Markiewicz’s disregard for the historical and social conditions of the place in which he sought to operate. As Vishmidt points out, the speculative logic of neoliberalism, while ostensibly offering artistic emancipation through autonomy, ultimately fails to account for local contexts and historical infrastructural dependencies. The attempt to impose this model in Płock met with resistance and a lack of dialogue between new and traditional institutions, preventing the formation of a cohesive artistic community or a sustainable discourse around contemporary art.

A Gallery from Surplus

Markiewicz’s determination to run a gallery in his hometown of Płock – despite being offered the directorship of the Dziekanka gallery at the Academy of Fine Arts in Warsaw – exemplifies his vision of artistic autonomy as a project fundamentally tied to individual entrepreneurship. A year before opening the gallery, in 1991, he set up FOL-CUP, a wholesale company specializing in disposable packaging. He consistently emphasized that this business served as the financial foundation for his artistic practice. As one press article noted, ”Jacek can be found in the warehouse he runs to earn money to make art, although he never thought about money, dealing with another side of life. Today he knows that art needs money. Hence the warehouse.”29 This model not only reflected the neoliberal concept of the entrepreneurial subject but also introduced a paradoxical separation between the spheres of work and art – distinct yet inextricably linked. The material conditions of their coexistence highlighted this contradiction: in the 1990s, both the gallery and the warehouse were located in the same building at ul. Rybaki 7.

The a.r.t. gallery, sustained by the financial surplus generated by the FOL-CUP wholesale business, reveals a distinct relationship between work and non-work, exposing the speculative logic of capitalism. The warehouse – an archetypal workspace, structured by the principles of capital accumulation and exchange value – became the economic bedrock for the gallery, which functioned as a space of non-work. The gallery, existing within the symbolic autonomy of art, was neither profit-driven nor designed to generate financial returns. Yet, while Markiewicz’s artistic practice consciously distanced itself from direct engagement with the market, it remained indirectly dependent on surplus capital produced through conventional economic activity.

Although the a.r.t. gallery did not generate direct profits, its operation can be interpreted as a form of speculation in symbolic value. In the United States, the art market itself legitimized artistic worth; in Poland, where a contemporary art market was virtually nonexistent, Markiewicz’s activities focused on the production of symbolic capital. Here, art was not treated as a commodity but as an investment in future value. This model aligned with the capitalist logic of accumulation through added value: the gallery functioned to establish the artist’s legitimacy as an autonomous subject, providing a space for free and independent artistic production. However, as Vishmidt argues, the autonomy of art is ultimately an illusion – art is never truly separate from labor. Instead, it operates within labor as a specialized form of activity, playing a crucial role in the production of both economic and symbolic value.

Jacek Markiewicz: The Entrepreneurial Subject

Dardot and Laval define the entrepreneurial subject as an individual shaped by neoliberal rationality, perceiving themselves as a ”self-enterprise.”30 This subject is responsible for independently managing their life through rational calculation, risk-taking, and the pursuit of maximum efficiency. Internalizing control and evaluation mechanisms, they continually strive for self-improvement and the fulfillment of both social and market expectations. Within this framework, Vishmidt argues that artists operating under closed speculation adopt a similar logic, effectively becoming self-entrepreneurs.31 In this model, the artist is an entity that must continuously invest in their own skills, image, and productivity to maintain relevance within a system where artistic value is no longer tied to material production but to symbolic valorization in the market. Responsibility for survival and success, once supported by public institutions or the state, is now entirely transferred to the individual. The artist thus becomes both a producer and a manager, subjecting themselves to self-imposed discipline. This process conflates artistic autonomy with financial independence, compelling artists to navigate their careers according to the principles of competition and market efficiency. I argue that the strategy adopted by Markiewicz inevitably positioned him within the logic of neoliberalism.

Markiewicz’s image as an artist-entrepreneur encapsulates the ambivalence inherent in the concept of the entrepreneurial subject. On the one hand, he deliberately maintained an ironic distance from market norms and mechanisms; on the other, he actively participated in these structures, benefiting both materially and symbolically from their legitimizing power.32 In the theoretical appendix to Adoracja, Markiewicz reflected on his experience at the 4th Polarcup Distributors’ Conference: ”I decided to take the tram after my walk, but my outfit [suit – author’s note] was a barrier. Everyone waiting at the bus stop would have preferred to see me in a taxi rather than standing next to them.”33 This anecdote – at once exaggerated and rooted in real experience – demonstrates how Markiewicz played with middle-class perceptions, using the suit as a manifestation of transformative success.

In the 1990s, Markiewicz and Katarzyna Kozyra would purchase elegant suits, pantsuits, and shoes, and then attend packaging trade shows together, exaggerating the personas of middle-class success.34 The figures of the businessman and businesswoman, performed by Markiewicz and Kozyra, are particularly interesting in light of Vishmidt’s concept of the entrepreneurial subject. As Vishmidt notes, under capitalism, individuals are shaped as resources subordinated to the logic of capital self-valorization. The artist-entrepreneur – creatively autonomous and financially self-sufficient – not only sustains this logic but fully embodies it. By attending packaging fairs in business attire, Markiewicz and Kozyra enacted a form of capitalist drag – a performative engagement with middle-class aspirations and the phantasm of transformative success. Yet, as Markiewicz himself later recalled, these excursions were not merely artistic interventions. He was genuinely representing his wholesale business, while Kozyra and her sister were seriously considering launching their own enterprise, consciously investing in their professional image.

This blend of irony and pragmatism reveals the ambiguity inherent in the speculative construction of a new subjectivity – one that simultaneously undermined the oppressive logic of transformation while embedding itself within the very process of self-valorization. In this model, artistic independence and economic survival become deeply entangled. Yet the irony that lent these activities their critical dimension was also rooted in a sense of superiority derived from the symbolic capital of art.35 By participating in the producers’ fair not only as aspiring entrepreneurs but also as artists, Markiewicz and Kozyra reinforced their own status. From a position of aesthetic detachment, they could both engage with and satirize the capitalist culture of success. In this way, they exemplified what Dardot and Laval describe as the ambivalence of the entrepreneurial subject: simultaneously acting within the system while maintaining enough distance to critique it. This dual positioning ultimately allowed for a more strategic management of both material and symbolic capital. Here, the artistic background served as a tool for strengthening competition between the entrepreneurial subjects.

Although Markiewicz’s and Kozyra’s actions appeared to function as ironic critiques of the capitalist culture of success, they also exposed a deeper issue: the neoliberal appropriation of art as a space of non-work. Their performative gestures – attending trade fairs in business attire, oscillating between irony and sincerity – transcended the conventional boundary between work and art. Neither fully embedded in the art world nor entirely assimilated into the market logic, they found themselves enmeshed in neoliberal dynamics of flexibility and self-valorization, embodying what can be described as the creative precariat – subjects perpetually negotiating their value on the threshold between work and non-work.

Within the neoliberal system, art, once positioned as a space of autonomy and critique, is increasingly reduced to a mechanism for reinforcing competitive relations. Rather than dismantling dominant structures, the artist adapts to their demands. Flexibility, apparent independence, and the erasure of distinctions between work and non-work do not facilitate emancipation but instead entrench neoliberal forms of exploitation. In the case of Markiewicz and Kozyra, we see how ostensibly performative critiques of the system simultaneously contributed to its reproduction. Even as they maintained a rhetorical distance from its principles, they remained bound within its structures, reinforcing the logic of precarization and market efficiency.

At this point, it is worth noting that in the 1990s, Markiewicz perceived no real alternative to the economic realities imposed by the transition. Running a wholesale business was not merely an economic strategy but a means of financing artistic practice independently of institutions. By the mid-1990s, Markiewicz had started a family, which redefined his approach to both capital and art. Reproductive labor and the demands of everyday life began to intersect with artistic production; economic risk was no longer an individual concern but one that affected his entire household.

Economic pressures and the absence of infrastructural support for artists meant that the entrepreneurial subject was not just an ideological construct but also a survival strategy in the precarious landscape of the 1990s. The financial stability of Markiewicz’s business, initially conceived as a condition for artistic autonomy, became a necessity for sustaining family life. Like many cultural workers, Markiewicz was not only an entrepreneur of his own creativity but also a manager of reproduction, overseeing both his career and the material conditions of domestic life. This dynamic illustrates how neoliberal transformation not only reshaped artistic strategies but also forced them into direct alignment with economic survival. Ultimately, artistic autonomy and market flexibility emerged as two sides of the same coin.

Adoration of Transformation

From June 11 to 26, 1994, the Water Tower exhibited Jacek Markiewicz’s graduation project, titled Adoracja [Adoration]. The film depicts the naked artist adoring a crucifix from the National Museum in Warsaw, hugging and kissing it. Interestingly, it was not Markiewicz’s diploma work but Kozyra’s Piramida zwierząt [Pyramid of Animals], defended in the same year, that ignited controversy and sparked a nationwide debate. Adoracja, despite touching on sensitive religious issues, did not cause a comparable reaction; when it was presented at the State Art Gallery in Sopot in 1992, it went largely unnoticed. Markiewicz recalls that a bishop attended the vernissage, solely to bless the newly opened gallery; his reaction to the work did not betray any outrage.36 This lack of response is particularly surprising given that it occurred during a period when the Church was demanding the return of sacred art from public institutions. Evidently, the work did not function as a scandalous transgression of the sacred sphere, suggesting that its critical potential lay elsewhere.

In this context, the version of Adoracja as it was presented during Markiewicz’s graduation should be mentioned. I believe that the key to this version of the artist’s installation is not the figure of Christ himself, but the post-communist figure of the child-son. The installation consisted of a box whose aesthetics triggered associations with a trade fair stall or an office interior. Inside, a film was shown featuring the naked artist adoring a medieval crucifix. A monitor installed outside displayed the reactions of the viewers inside the box. During the defense of his diploma, the artist’s father and one of his employees temporarily became part of the installation – they were to see it for the first time. This encounter revealed a peculiar relationship: on one hand, Markiewicz is his father’s child, with his role as a son emphasized by his closeness to the son of God; on the other hand, within a capitalist market framework, it is the father, working in his son’s company, who is infantilized as the son’s employee – he becomes a ”child” of the business activity conducted by the son-father. One of the monitors showed the faces of both the father and the employee, allowing viewers to decide if, instead of watching the film, they preferred to observe how Adoracja affected these two individuals. In doing so, Markiewicz exposed all the actors to humiliation in this personal and economic process of infantilization.

Jacek Markiewicz, detail from his graduation work – the artist’s father and an employee watching Adoracja [Adoration], Warsaw, 1993, from the private archive of Jacek Markiewicz

Buden’s figure of the child is pivotal for understanding post-communist transformation. According to the Croatian philosopher, after the fall of communism the societies of Central and Eastern Europe were treated by the West as children in need of education – immature subjects who had to undergo a process that would prepare them for adulthood, i.e. functioning within Western liberal capitalism.37 In this sense, the child becomes a metaphor for post-communism: innocent yet incomplete and devoid of autonomy. The figure reflects the unequal power relationship between East and West, where the former is forced into dependence on the ”teacher” within hegemonic modernization narratives. Buden further points out that the West also infantilized the worker – one of the actors of the democratic revolution of 1989 – depriving him of maturity and agency, and condemning him to blindly accept Western ”normality.”

Markiewicz thus orchestrates an ambivalent situation in Adoracja, where the figure of the child becomes the nexus between the past and the future, between religious tradition and the modernity of body and video art. This child simultaneously represents Markiewicz himself – a budding capitalist and contemporary artist who must ”learn” his trade to mature into marketable, artistic adulthood – and his father, who is ”educated” and disciplined in the realm of contemporary art, and in the company holds a lower status than his own son, effectively rendering him his ”child’s child.” The infantilization of the blue-collar father is vividly expressed in his shame and helplessness when confronted with radical art forms that defy understanding while symbolizing an autonomy that the working class could only dream of at the time.

It is worth reading this relationship through the prism of Vishmidt’s concept of speculative capitalism. In this model, the worker not only sells his labor but also becomes part of the logic of speculation – a managed resource whose value depends on his ability to adapt to the system’s requirements. Within the employment hierarchy of Markiewicz’s warehouse, the father, acting as a hired worker, becomes part of the enterprise’s infrastructure and is reduced to the function of a ”human resource,” subordinate to the orders of his son-employer. The artist delegated the task of watching the graduation film as an official order, and the father’s role – limited to passively watching the film during the diploma defense – highlights the lack of agency and flexibility that characterize the neoliberal ideal of the ”self-entrepreneur.” In this context, the father symbolizes the limitations of wage labor in a system where autonomy and risk are asymmetrically distributed – flexibility and the opportunity to speculate are available only to those who manage, not to those who do the work.

In this relationship, the alienation of labor becomes even more multidimensional than in Marx’s analysis. The father is estranged not only from his work in the warehouse but also from the meanings produced by the work of art. His shame and helplessness in the face of radical, body-centered, aesthetically autonomous art reflect the alienation inherent in capitalism’s transformative logic, which shifts risk and responsibility onto the individual. In the speculative framework, the father-worker emerges as a loser in the transformation: he neither comprehends his son’s artistic world nor possesses the tools to fully engage with a system demanding constant development and adaptation. Conversely, the artist-son is cast as a new kind of subject – a ”self-entrepreneur” who uses art as a space to negotiate between risk and value. However, his autonomy is achieved through violence: Markiewicz secures his artistic freedom at the expense of humiliating his father, who is reduced to a mere prop in the project. This tension exposes the deep paradox of speculative capitalism: the son’s creative freedom is possible only because the worker-father internalizes risk. In a system where individuals must manage themselves as enterprises, family and economic relationships are inextricably woven into the logic of the market. Through the interplay between father and son, work and art, Markiewicz reveals both the costs and the limitations of the new order, where freedom and autonomy always come at a price – risk and alienation.

Conclusion

The relationship between the a.r.t. gallery – operating on the margins of the art system as a space of ”non-work” – and the FOL-CUP company as a place of work in the most literal sense, captures the moment when art and capitalism began to lose their distinctiveness during the period of transformation. In this configuration, not only did the contradiction between the free and autonomous and that which is subordinated to the logic of accumulation collapse, but artistic practice also lost its emancipatory potential.

Artistic practice, which had once declared its separation from material production while inevitably relying on it, became integrated into the self-perpetuating logic of speculation. It generated nothing but abstract value that only made sense in relation to material labor. By absorbing art as a ”special” mode of value production, capitalism seemingly expanded its possibilities, yet it simultaneously weakened art’s potential to generate breakthroughs or alternatives to its own logic. Consequently, art became one of the mechanisms for reproducing processes of transformation rather than serving as a tool for their critical deconstruction. Ultimately, the fate of Markiewicz’s gallery – which disappeared – and that of the company – which survived – symbolizes art’s inability to function outside of capitalism.

The collapse of the a.r.t. gallery exposes the limits of the neoliberal model of art functioning. Despite its initial success and declared independence, by 2010 the gallery could no longer sustain itself without institutional support. The municipal authorities in Płock terminated the artist’s lease, leaving the gallery without a venue. Although the rent was offered at a preferential rate, the artist bore the full burden of maintaining and renovating the space. Subsequent crises, such as flooding of the interior, were met with no support from the city, rendering continued operation impossible. In practice, this situation duplicated the mechanisms of neoliberal self-financing art – not only for the artist but also for the municipal institutions, which had withdrawn responsibility for the conditions of its existence.

Paradoxically, the pursuit of artistic autonomy became entangled in the very logic that led to the gallery’s closure. Declared independence meant that the economic burden was shifted onto the artist himself, who not only had to organize a space for art, but also bore the full consequences of its operation in market conditions. At a certain point, Markiewicz no longer viewed investing in the gallery space as a choice, but rather as an imposed burden that transformed independence into another economic liability. In a context marked by the complete withdrawal of public institutions, independent art ultimately ceased to be possible.

Translated by Karol Waniek

Bibliography

Banasiak, Jakub. Proteuszowe czasy. Rozpad państwowego systemu sztuki 1982–1993. Akademia Sztuk Pięknych w Warszawie and Muzeum Sztuki Nowoczesnej w Warszawie, 2020.

Buden, Boris. Strefa przejścia. O końcu postkomunizmu. Translated by Michał Sutowski. Wydawnictwo Krytyki Politycznej, 2012.

Buraczyński, Bogusław. ”Galeria ART w Płocku.” Głos Poranny no. 122 (1992): 4.

Dardot, Pierre, and Christian Laval. The New Way of the World. Verso, 2013.

Gala, Marek. ”Jacek Markiewicz i jego galeria ‘a.r.t.’” Gazeta na Mazowszu, no. 67 (1993): 5.

Kozioł, Wiktoria. Polska sztuka krytyczna na tle transformacji po 1989 roku. PhD diss., Uniwersytet Jagielloński, 2019.

Lewandowska, Anna. ”Inna niż państwowa.” Gazeta na Mazowszu, no. 242 (1993), 3.

Petrossiants, Andreas. ”Spaces of Speculation: Movement Politics in the Infrastructure. An Interview with Marina Vishmidt.” Historical Materialism, November 14, 2020.

Rakiel-Czarnecka, Walentyna. ”Kulturze na ratunek.” Nowy Tygodnik Płocki, no. 13 (1992): 10.

Sienkiewicz, Karol. Zatańczą ci, co drżeli. Polska sztuka krytyczna. Karakter, 2014.

Stakemeier, Kerstin, and Marina Vishmidt. Reproducing Autonomy: Work, Money, Crisis & Contemporary Art. Mute Publishing, 2016.

Szatkowska, Lena. ”Artysta na Rybakach.” Tygodnik Płocki, no. 34 (1992), 7.

Szczerski, Andrzej. Transformacja. Sztuka w Europie Środkowo-Wschodniej po 1989 roku. Wydawnictwo Uniwersytetu Jagiellońskiego, 2018.

Szcześniak, Monika. Normy widzialności. Tożsamość w czasach transformacji. Fundacja BęcZmiana, Instytut Kultury Polskiej UW, 2016.

Szymczyk, Adam. a.r.t 1992–1997. Galeria a.r.t, 1997.

Vishmidt, Marina. ”From Speculation to Infrastructure: Material and Method in the Politics of Contemporary Art.” OnCurating, issue 58 (March 2024): 17–25.

Vishmidt, Marina. Speculation as a Mode of Production. Forms of Value Subjectivity in Art and Capital. Brill, 2018.

Vishmidt, Marina. ””Only as Self-Relating Negativity”: Infrastructure and Critique.” Journal of Science and Technology of the Arts 13, no. 3 (2021).

Woźniak, Agnieszka. ”Spowiedź Jacka Markiewicza. Rozmowa o galerii a.r.t.” Gazeta Wyborcza – Płock, Wednesday, January 23, 2008, 2.

Zaremba, Łukasz. Obrazy wychodzą na ulicę. Spory w polskiej kulturze wizualnej. Fundacja Bęc Zmiana, Instytut Kultury Polskiej UW, 2018.

- In a 2013 article Jacek Markiewicz i akt chrześcijański [Jacek Markiewicz and a Christian Act] Paweł Leszkowicz wrote: ”Jacek Markiewicz is an artist who has fallen into oblivion and disappeared from the art scene in recent years.” However, this disappearance is largely due to art historians’ lack of interest in the artist’s work that he then created – and still creates. In 2011, Markiewicz produced the work Porno, exhibited at the Sztuczna Foundation in Warsaw. Three years later, as part of the Crimestory exhibition at CSW Znaki Czasu in Toruń, he presented Spowiedź [Confession] – a film without images, in which he confessed his art to a priest in a confessional. In 2015, he carried out the project Moje marzenie [My Dream], in which he recorded conversations with incarcerated women about their most important desires, undertaking to realize one of them. In an interview conducted for this article, the artist revealed that he has been working on a new project for a year. ↩︎

- The only document related to the gallery’s activity is the catalog a.r.t. 1992–1997, which compiles information about the exhibitions organized during those years. The publication includes short excerpts from selected articles from the local press in which journalists commented on the exhibitions. However, it does not provide any information related to the gallery’s history, the choice of its location, or the local context. ↩︎

- See M. Szcześniak, ed., ”Realizm kapitalistyczny. Transformacje kultury wizualnej lat 80. i 90″ [Capitalist Realism: Transformations of Visual Culture in the 1980s and 1990s ], Widok, no. 11, 2015; M. Szcześniak, Normy widzialności. Tożsamość w czasach transformacji [The Norms of Visibility: Identity in Times of Transformation] (Warsaw: Fundacja Bęc Zmiana, Instytut Kultury Polskiej UW, 2016); Ł. Zaremba, Obrazy wychodzą na ulicę. Spory w polskiej kulturze wizualnej [Images Take to the Streets: Disputes in Polish Visual Culture] (Warsaw: Fundacja Bęc Zmiana, Instytut Kultury Polskiej UW, 2018); J. Banasiak, Proteuszowe czasy. Rozpad państwowego systemu sztuki 1982-1993 [The Protean Times: The Collapse of the State Art System 1982–1993] (Warsaw: Akademia Sztuk Pięknych w Warszawie, Muzeum Sztuki Nowoczesnej w Warszawie, 2020); A. Szczerski, Transformacja. Sztuka w Europie Środkowo-Wschodniej po 1989 roku [Transformation: Art in Central and Eastern Europe after 1989] (Kraków: Uniwersytetu Jagiellońskiego, 2018); W. Kozioł, Polska sztuka krytyczna na tle transformacji po 1989 roku [Critical Polish Art in the Context of the Transformation after 1989], PhD diss., Jagiellonian University, 2019. ↩︎

- M. Vishmidt, ”From Speculation to Infrastructure: Material and Method in the Politics of Contemporary Art,” OnCurating, issue 58 (March 2024): 18. ↩︎

- M. Vishmidt, Speculation as a Mode of Production. Forms of Value Subjectivity in Art and Capital. Leiden: Brill, 2018, 15. ↩︎

- K. Stakemeier and M. Vishmidt, Reproducing Autonomy: Work, Money, Crisis & Contemporary Art. London and Berlin: Mute Publishing, 2016, 36. ↩︎

- On post-communism as a hegemonic discourse of transitology that legitimizes inequalities and the dominance of the West by presenting transformation as a linear process of modernization – while in reality concealing the economic, social, and cultural violence associated with abandoning the socialist past – see: B. Buden, Strefa przejścia. O końcu postkomunizmu [The Transition Zone: On the End of Post-Communism], trans. Michał Sutowski (Warsaw: Wydawnictwo Krytyki Politycznej, 2012). ↩︎

- P. Dardot and C. Laval, The New Way of the World. London and New York: Verso, 2013. ↩︎

- See K. Sienkiewicz, Zatańczą ci, co drżeli. Polska sztuka krytyczna [They Will Dance, Those Who Trembled: Critical Polish Art] (Warsaw: Karakter, 2014); Kozioł, Polska sztuka krytyczna na tle transformacji. ↩︎

- Articles from the 1990s contain erroneous information that this was a scholarship which the artist was supposed to receive as a prize in a competition, see B. Buraczyński, ”Galeria ART w Płocku” [Galeria ART in Płock], Głos Por., no. 122 (1992): 4. Today Markiewicz claims that it was not a scholarship but a self-financed trip. ↩︎

- M. Gala, ”Jacek Markiewicz i jego galeria a.r.t.” [Jacek Markiewicz and his a.r.t. Gallery], interview, Gazeta na Mazowszu, no. 67 (1993): 5. ↩︎

- L. Szatkowska, ”Artysta na Rybakach” [Artist in Rybaki], Tygodnik Płocki, no. 34 (1992): 7. ↩︎

- Ibid. ↩︎

- Interview with the artist, December 13, 2024. ↩︎

- In this context, the artist’s contacts with the Batory Foundation are of interest. Markiewicz mentioned them in an interview on December 13, 2024, indicating that both the Kowalnia milieu and the a.r.t. gallery maintained a relationship with the Foundation. The Soros Centers, as instruments of Western liberalization of cultural institutions during the transformation period, could be one of the factors influencing the functioning of the a.r.t. gallery. However, further research into Markiewicz’s private archive regarding the gallery’s activities is required, as the artist is currently not making the materials available. ↩︎

- Buden, Strefa przejścia, 17. ↩︎

- Vishmidt, Speculation as a Mode of Production, 21. ↩︎

- Ibid., 87. ↩︎

- A. Petrossiants, ”Spaces of Speculation: Movement Politics in the Infrastructure. An Interview With Marina Vishmidt,” Historical Materialism, November 14, 2020. ↩︎

- M. Vishmidt, ”Only as Self-Relating Negativity: Infrastructure and Critique,” Journal of Science and Technology of the Arts 13, no. 3 (2021): 19. ↩︎

- Banasiak, Proteuszowe czasy, 429–453. ↩︎

- Interview with the artist, December 13, 2024. ↩︎

- Vishmidt, From Speculation to Infrastructure. ↩︎

- W. Rakiel-Czarnecka, Kulturze na ratunek [To the Rescue of Culture] Nowy Tygodnik Płocki, no. 13 (1992): 1, 10. ↩︎

- Ibid. ↩︎

- Szatkowska, Artysta na Rybakach. ↩︎

- I. Lewandowska, ”Inna niż państwowa” [Unlike a State-run], Gazeta na Mazowszu, no. 242 (1993): 3. ↩︎

- A. Woźniak, ”Spowiedź Jacka Markiewicza. Rozmowa o galerii a.r.t” [The Confession of Jacek Markiewicz. A Conversation about the a.r.t. Gallery]. Gazeta Wyborcza Płock (January 23, 2008): 2. In his statement, the artist mentions the largest department store in 1990s Płock, Tayger, and to the markets commonly known as ”Manhattan,” which emerged in many Polish cities during the transformation period. His emphasis that in 2008 they still served as an important consumption hub for the people of Płock was meant to indicate that the city had become a loser in the transformation and had stalled early in the process of catching up with the West. ↩︎

- Szatkowska, Artysta na Rybakach. ↩︎

- Dardot, Laval, The New Way of the World. ↩︎

- Vishmidt, Speculation as a Mode of Production, 35–38. ↩︎

- It is worth emphasizing that the artist often referred in his work to the business aspect of his life. At the 2002 exhibition Sposób na życie [A Way to Live] at CSW Łaźnia, he presented a work displaying a live stream from his warehouse in Płock, where he was working in real time, attending to clients, and distributing goods. ↩︎

- Kozioł, Polska sztuka krytyczna, 217–218. ↩︎

- Interview with the artist, December 13, 2024. ↩︎

- The artist mentions that, among other things, he included his business experiences in the theoretical supplement to his diploma in order to counterbalance that aspect of the reality in which he found himself as both an artist and an entrepreneur. Interview with the artist, December 13, 2024. ↩︎

- Markiewicz, in response to the author’s questions (December 2, 2024). In Sopot, Adoracja was displayed on televisions arranged in the shape of a Latin cross. ↩︎

- Buden, Strefa przejścia, 39. ↩︎

Karolina Wilczyńska

Karolina Wilczyńska is currently a doctoral candidate at the Institute of Art History at Adam Mickiewicz University in Poznań and is affiliated with the Piotr Piotrowski Center for Research on East-Central European Art. Her dissertation focuses on Mierle Laderman Ukeles’ maintenance art, analyzed through the lens of reproductive labor and infrastructural critique. Wilczyńska is a researcher in the grant project Understanding 1989 in East-Central European Art: War vs. Revolution. She has also contributed to the project The Legacy of Piotr Piotrowski and co-organized the East-Central European Art Forum. In 2019, she was awarded a Library Research Grant at the J.F. Kennedy Institute for North American Studies in Berlin. She is also a Fulbright scholar (Fulbright Junior Research Award 2021) at CUNY in New York.