Title

Revitalizing the Archive A Transformative History of the “Fajans” Museum in Włocławek

https://doi.org/10.48285/ASPWAW.29564158.MCE.2024.10.5EN

regional museum, women’s history, transformation, faience, “Fajans” Museum Włocławek

https://miejsce.asp.waw.pl/en/rewitalizacja-archiwum/

Abstract

This article traces the genesis, dissemination, and reception of the concept behind the “Fajans” Museum in Włocławek, reconstructed on the basis of materials drawn from the Archival Collections of the Faience Department at the Museum of Kujawy and Dobrzyń Lands in Włocławek. The archival inquiry into the non-existent “Fajans” Museum pursues a dual aim: first, to offer a detailed examination of the underlying factors that ultimately thwarted the institution’s establishment; and second, to explore the speculative dimension of what the museum might have become. The text delves into the debates surrounding the museum’s conception during the late socialist era and the period of political transformation, proposing the activation of the archive of this uncreated museum as part of an art historical endeavor. By contemplating potential continuations of what may be regarded as the “Fajans” Museum’s legacy, the article raises the question of transformation within the broader historical context of women’s labor, with particular emphasis on the contributions of faience painters.

Keywords

regional museum, women’s history, transformation, faience, “Fajans” Museum Włocławek

DOI

Bulldozer

In September 1974, a bulldozer razed an outdoor exhibition of independent artists in Moscow – an event that acquired legendary status as the so-called “bulldozer exhibition” and became etched in the annals of twentieth-century art as an enduring symbol of Soviet iconoclasm.1 With this afterimage in my mind, I watch the closing sequences of the film Kronika Fabryki Fajansu [Chronicle of the Faience Factory], shot that same year by Andrzej Papuziński at the Revolution of 1905 Faience Factory in Włocławek (in short, Włocławek “Fajans”). The cameraman was Zbigniew Rybczyński, who would later win an Academy Award for his short film Tango and direct music videos for artists such as Lou Reed and the Rolling Stones.2 While it is unlikely that Papuziński was aware of the events unfolding simultaneously in Moscow, he must have employed the image of the bulldozer intentionally, as a narrative device heralding the radical conclusion that his film foreshadows. The final scene, lasting just over a minute, is accompanied by a radio broadcast excerpt announcing plans to relocate the faience factory to a new site.

Still from Andrzej Papuziński’s film Chronicle of the Fajans Factory, 1974 © Wytwórnia Filmów Oświatowych Sp. z o.o. / The Educational Film Studio

We see a machine obliterating tons of multicolored, probably flawed, faience vessels. Although the filmmakers conceived this sequence as an allegory for the factory’s demise, it resonates on a broader level – as an omen of the sweeping transformations that would change this place after 1989.

Łukasz Zaremba writes about the absence of a singular iconoclastic gesture to symbolize systemic change in Poland.3 The aforementioned frames capture a transformative iconoclastic act on a micro-scale, several years before the factory’s actual closure in 1991. The bulldozer metaphor proves particularly resonant in the context of faience: here we are confronted with inherently fragile objects, created as a result of countless hours of collective labor, yet also emblematic of the cultural policy of socialist Poland – the collective product of a workers’ culture. Covered in cobalt or adorned with multicolored floral patterns, the włocławki were immensely popular during the state socialism, gracing the interiors of most households. Painted by hand by women workers, often according to their own designs and sometimes following original patterns created by artists employed at the factory, these pieces drew on the visual language of folk art.4 Thus, the bulldozer metaphor can be extended to encompass the consignment to collective amnesia of the legacy of worker-painters’ creativity – an egalitarian form of artistic production long championed by both central and regional cultural institutions.

Karolina Bandziak-Kwiatkowska, head of the Faience Department at the Museum of the Kujawy and Dobrzyń Lands (Muzeum Ziemi Kujawskiej i Dobrzyńskiej, MZKiD) in Włocławek, drew my attention to the deeper significance of this scene – a kind of prefiguration of the faience factory’s fate after 1989. The museum’s collections include the archive of the factory’s pattern shop, collections of faience hand-painted by factory workers between 1945 and 1991, as well as a trove of prewar wares from Włocławek’s earlier faience manufactories. The Faience Department is dedicated to the research and presentation of objects reflecting the city’s industrialization and the socialist-era cultural entanglement of factory and museum.

If the material heritage of the faience factory is the focus of the regional museum and other local institutions, then this article poses the question of the significance and potential inherent in the legacy of the unrealized “Fajans” Museum. To this end, I undertake to reconstruct the history of the project whose implementation was ultimately interrupted during the period of systemic transformation.

The experience and social memory of the transformation, as well as its consequences for specific professional groups in post-industrial regions, have been the subject of extensive analysis and reflection, often grounded in oral history.5 Yet, in turning to the history of the uncreated “Fajans” Museum, I do not seek traces preserved within local social memory. Indeed, the Museum has been largely effaced from that memory, its interrupted history having thus far eluded scholarly inquiry. Accordingly, the discourses of memory culture and historical politics have been set aside here in favor of a focus on practice and critical reflection on the problem of archival activation – a process I define, by analogy with museum-building practices, as the revitalization of the archive.

In this article, I reconstruct the genesis, dissemination, and reception of the concept behind the “Fajans” Museum through extant archival materials, asking what contemporary meanings and possible uses might be derived from them. The study of the traces left by the “Fajans” Museum pursues two parallel aims: first, to explore why the institution ultimately failed to materialize; and second, to address the speculative question of what it might have become. My proposition is to revitalize the archive of the “Fajans” Museum within the framework of what I term “transformative art history,” the principles of which I will outline in the first part of the text.

In the subsequent section, I will trace the history of the “Fajans” Museum concept and analyze the debates surrounding it in the local press throughout the 1970s and 1980s. Drawing upon architectural and construction documentation preserved in the MZKiD archive, I will look at the successive phases of the project. I will then turn to the discussion that unfolded around the Museum at a 1973 expert symposium in Włocławek, and compare it with the proceedings of the 1994 conference at MZKiD, which was an attempt to revive the debate on the industrial heritage of socialism amid new economic realities.

In the final section, I will reflect on potential forms of continuation for what has been cast as the legacy of the non-existent “Fajans” Museum. Here, I will address questions of gendered transformation in the context of the history of the women painters whose labor imbued Włocławek faience with its value, as well as the experts shaping the transdisciplinary discourse on faience today. The latter aims to intervene in the historical narrative of capitalist modernization in Poland by reintroducing the speculative “Fajans” Museum into the institutional landscape of transformation – as a center devoted to the history of women’s labor.

Towards a Transformative Art History

Conceived in the 1970s and analyzed in detail below, the idea of the “Fajans” Museum emerged within the broader discourse of Gierek-era modernity, with its aspirations not only to partake in economic exchange but also to engage in cultural dialogue with both East and West. By the 1990s, however, the Museum had devolved into a bankruptcy estate, and the discourse surrounding it centered on the twilight of socialism and its lingering ruins. Viewed from today’s vantage point, what proves most compelling in this discussion are the alternative pasts of the late socialist and transformation periods. To reveal these, we may pose the speculative question: What kind of museum might the “Fajans” Museum have become, had it ever materialized?

The potential history to which this question alludes is situated within a decolonial perspective that conceives of history itself as an imperial domain. At its core lies a project aimed at destabilizing the institution of the archive. Decolonial historians contend that both archives and museums overwhelmingly house sources and resources tied to dominant social groups – and thus must be radically reimagined. On this foundation, Ariella Aïsha Azoulay articulates the project of potential history as “a commitment to attend to the potentialities.”6 In the absence of formal archives, decolonial scholars advocate for the activation of speculative histories, grounded in the exercise of a decolonized imagination. Historians such as Saidiya Hartman, following Donna Haraway, advance the method of critical fabulation as a form of transformative historiography – one that seeks to recover and update the legacies of marginalized subjects, presenting them as active makers and shapers of history.7 These scholars insist that merely critiquing institutional mechanisms of selection and exclusion is insufficient. The essence of these strategies is not the invocation of fantasy as a psychoanalytically inflected critical tool, as Joan Wallach Scott explores in The Fantasy of Feminist History,8 but rather the emancipatory and ethical potential of imagination in the process of unlearning entrenched frameworks – through the creation of new objects and subjects of historical narrative.

However, when engaging with the histories of socialism and capitalist transformation, we are dealing with archives that represent marginalized social groups – archives whose significance, and thus the attention they received from art historians, diminished sharply after 1989. Unlearning them is not necessary because we are operating in a field of active negation and forgetting. Archives have become neglected because they served communities and were activated by a socialist infrastructure that no longer exists.9 The process of studying them can thus be aptly described by the term revitalization – “restoration, reviving” – which comprises both a stage of recognition and a stage of reassigning meaning in light of contemporary challenges. Local and national archives from the late socialist and transformative periods, therefore, demand not only a radical imagination but also a radical attentiveness in rereading them, particularly in relation to the ruins with which they remain entangled.

The “Fajans” Museum is, both metaphorically and materially, a ruin from the era of state socialism. The act of imbuing this ruin with new meaning found expression in the revitalization project and the creation of a new city center, completed in 2008.10 But how to confront this ruin within a transformative historical narrative? Feminist historian Alison Poe draws attention to the positive excitement that historians often experience in the face of fragmentation.11 This, she argues, frequently leads to the aestheticization of ruins – an opportunity to exercise expertise, assert one’s voice, or demonstrate creativity. Poe defines incompleteness as a condition that enables one to enter the past and participate in its co-creation, proposing the activation of feminist networks of care instead of the mere performance of expertise. She advocates for filling the gaps found within the porous histories and fragmented material remains of antiquity – the very legacy upon which Western imperialism is built – with the stories of the subaltern: slaves, peasants, women.

Yet the activation of such networks of care need not remain confined to narratives about antiquity; it can become an integral part of a transformative historical narrative that challenges the hegemony of the modern neoliberal order as the sole model of social organization. In this sense, the adjective “transformative” refers not only to the historical period conventionally designated as such, but also acquires an activist dimension, borrowed from the framework of potential history. By transformative art history, then, I mean narratives concerned with representing that which has been marginalized or dismissed as insignificant (such as “Fajans” or the “Fajans” Museum ), but also those open to alternative modes of knowledge production about the past, including speculative inquiry. It involves posing questions about possible pasts and attending to hybrid objects situated at the intersection of art and materials traditionally deemed incomplete.

Such a perspective also reshapes how we understand archives, aligning with the strategies of archival activation practiced within the realm of artistic research, where forgotten histories are transformed through integration of fact and fiction.12 In the case examined here, the archive of the non-existent “Fajans” Museum, now housed within the regional museum’s archival collection, is revitalized as a tool of crucial importance: one that not only expands our understanding of the culture of state socialism and political transformation, but also illuminates the very mechanisms by which this knowledge is categorized and produced.

Plans

In 1963, the National Council of Włocławek resolved to relocate the “” factory – which had operated in the city center since the mid-nineteenth century – to a new site. The transition was scheduled to take place within fifteen years, by 1978.13 “The unfortunately situated factory is suffocating the city’s residential quarters,” its director asserted.14 Plans were drawn up to establish a new shopping and service center within the historic buildings of the former factory. However, this proposal met with resistance from local cultural activists and museum professionals, who contended that the former factory should instead be repurposed to house a museum.

The factory was, indeed, situated in an inconvenient location. When it was established in 1873, Włocławek was a modest industrial center with a population of approximately 22,000. Over the course of the Second Polish Republic and later under the People’s Republic of Poland, the city underwent a significant population boom, transforming into a mid-sized industrial town with a population reaching 100,000 by the late 1970s. What had once been a factory positioned on the city’s outskirts had, through the course of urban expansion, found itself at the very center.

The tradition of Włocławek “Fajans” is connected with the transnational industrial history of the former Russian partition. During the period of industrialization at the turn of the twentieth century, factories operated by Jewish entrepreneurs produced faience using clay sourced from Halle. Several factors facilitated this industrial expansion: access to water transport via the Vistula River, the presence of an iron railway line, the wide availability of inexpensive labor, and the advantage of duty-free distribution within the Russian Empire. In the interwar period and throughout the Great Depression, the “Fajans” factories underwent numerous ownership and structural transformations, while workers, laboring under exploitative conditions, organized repeated strikes and protests. After World War II, the previously independent factories were nationalized and consolidated, culminating in the formation of the Polish United Faience Factories, which in 1956 was renamed Włocławskie Zakłady Fajansu im. Rewolucji 1905 – The Revolution of 1905 Faience Factory in Włocławek.

After the war, the factory began producing both tableware and decorative faience, all hand-painted by women workers. The factory embodied, on the one hand, the ideals of a national culture shaped by the popular classes, and on the other, it functioned as a living museum of the labor movement. The stories of interwar strikes and the organization of worker activism were documented by the workers themselves and are now preserved in the archives of the MZKiD.15 Faience from Włocławek reached the height of its popularity among consumers in the 1970s, during the period of prosperity under Edward Gierek. It was showcased at both domestic and international exhibitions, particularly in other socialist countries, and was frequently presented not merely as a folkloric product but as a symbol of Poland’s economic achievements and its national path toward socialism. For example, at an exhibition in Novi Sad in 1978, organized as part of cooperation between the two cities, the faience was displayed at the Workers’ University; a year later, in Leningrad, it was featured at an exhibition dedicated to the labor movement in Włocławek.

Despite the immense popularity of its products, the factory continually grappled with technical challenges, and working conditions remained exceedingly primitive – much of the machinery and equipment still dated back to the late nineteenth century. As a result, the decision was made to modernize operations and, consequently, to relocate the factory to a new site. It was during this period that the idea first emerged to transform the historic factory buildings into a “Fajans” Museum.

Initiator

In the lead-up to the factory’s relocation, consultations were initiated at both the local and provincial levels. In 1975, the MZKiD organized a session devoted to the future of the factory within the broader context of cultural heritage preservation. Local politicians, heritage conservationists, and the directors of the district museums in Bydgoszcz and Toruń were invited to participate. The papers presented at the conference addressed the development of a program for the protection of “national cultural property in the field of technology.”16 The proposal to transform the factory into a “Fajans” Museum was also taken up. A necessary precursor to this project was the formal inclusion of the factory in the register of monuments – and it was in this context that the debates inaugurated at the time over what constitutes a technological monument must be understood.

As reported in the Alchemik magazine’s account of the conference, the city’s residents actively engaged in the discussions surrounding the plans to demolish the century-old factory, relocate production to a new pavilion, and potentially build a service and commercial center on the site of the former plant. Notably, it is in this report that the concept of a “living ‘Fajans’ Museum” first appears. The overarching argument centered on the imperative to preserve the industrial heritage of earlier eras. I will now quote this description in full:

There are numerous considerations in favor of preserving the factory. First and foremost, it stands as a monument of technology and, as such, falls under the protective care of conservation authorities. Moreover, the oldest factory buildings present a unique opportunity to establish a “Fajans” Museum with an adjoining small-scale production facility. This will allow visitors not merely to admire the final product – the exquisitely hand-painted vessel – but also to observe and appreciate the various stages of its creation. Such an undertaking would carry enormous didactic value, offering the public a rare chance to encounter the historic machinery and equipment characteristic of a bygone manufacturing era. The removal of buildings lacking historical significance would, in turn, create space for the construction of an exhibition pavilion to house a permanent presentation of Włocławek faience, alongside rooms for occasional displays showcasing the best of Polish and international ceramics. The remaining grounds, once suitably developed, would become a verdant recreational area, complete with a Kujawy tavern furnished with characteristic regional fittings and serving local dishes. Conceived in this way, the museum center would stand unrivaled in the country and significantly contribute to the dynamization of tourism in the city.17

The concept for the “Fajans” Museum was developed by Romualda Hankowska, director of the Kujawy Museum (renamed the Museum of the Kujawy and Dobrzyń Land in 1975), who held this position from 1965 to 1976. A recognized expert in the technology and history of faience, Hankowska devoted her doctoral dissertation – published by Ossolineum in 199118 – to the history of the faience factories in Włocławek. She was among a circle of experts – including artist Elżbieta Piwek-Białoborska, ethnologist Barbara Zagórna-Tężycka, art historian Irena Huml,19 radio journalist Anna Jachnina,20 and Wanda Telakowska,21 founder and long-time director of the Institute of Industrial Design – who collectively shaped the transdisciplinary scholarly and expert discourse surrounding Włocławek “Fajans.”

Hankowska was also engaged in initiatives such as ceramic painting competitions and the development of sustained cooperation between the museum and the “Fajans” factory, which ultimately resulted in the creation of the Włocławek “Fajans” collection, now housed in the MZKiD. In 1973, this partnership culminated in the establishment of the “Fajans” Biennial, which was held regularly until the factory’s collapse in 1991. Press coverage of the Faience Biennial frequently mentioned the prospect of founding a “Fajans” Museum. The organization of the Biennial should therefore be understood as an integral component of the broader plan to establish this institution. One of the intended aims and outcomes of the Biennial was to create a dedicated museum collection: the award-winning works exhibited at the Biennial were systematically acquired by the regional museum, laying the groundwork for what was envisioned as the future core collection of the “Fajans” Museum.

The first article in the local press concerning the Museum appeared in 1974 in the magazine Gromada. Rolnik Polski. This suggests that the organization of the aforementioned conference should also be understood as part of the broader strategy to establish the Museum. In the anonymous article “Żywe Muzeum Fajansu” [Living ‘Fajans’ Museum], Gromada highlighted the popularity of Włocławek faience both domestically and abroad, while simultaneously asserting that only the establishment of a “Fajans” Museum would elevate the city’s cultural stature: “The creation of such an institution represents a great opportunity for Włocławek to become an original and valuable center on the cultural map of Poland.”22 These local ambitions converged the following year with the opportunities presented by Włocławek’s new administrative status as a provincial city, following the administrative reform of 1975.

The article also emphasized the intellectual and affective dimensions of the proposed museum – the experiences and forms of knowledge it could offer, designed not only to educate but also to provide “exciting experiences” through the opportunity to observe the production process firsthand. Hankowska herself played an active role in promoting the concept, publishing articles in the daily press to advance the cause. In 1975, in an article titled “Fabryka-Muzeum” [Factory-Museum] published in Kurier Ilustrowany, she reflected on the broader cultural shifts associated with increased leisure time (thanks to more days off work) and the growing popularization of domestic tourism. As Hankowska argued, every urban center, even one seemingly unremarkable, has the potential to offer something distinctive and original to “our countrymen voyaging across Poland.”23

The “tourism” argument and the accompanying vision of the Museum as a factor enhancing the city’s attractiveness is hardly coincidental; rather, it reflects one of the explicitly articulated priorities of the social policy of the time. As Barbara Pisarska observes, “given that one of the main factors in the development of tourism worldwide is the reduction of working time, it is worth recalling that Poland, until 1956, with 46 hours per week, was the country with the shortest working time in the socialist camp.”24 By 1975, this figure had been reduced further to 44.6 hours per week.

Hankowska’s line of argument also refers to the tradition of regional museums established in the Polish lands since the early twentieth century through the initiatives of sightseeing societies. This was also the genesis of the Kujawy Museum itself, founded in 1908 by the Kujawy Branch of the Polish Sightseeing Society. Such historical and contemporary genealogy of the proposed “Fajans” Museum thus stemmed from the fact that its conceptual architect was someone thoroughly acquainted not only with the history of museology but also with the intricacies and evolving directions of state cultural policy.

Hankowska also sought to win over the city’s residents, emphasizing the nonaesthetic value of the factory complex and appealing to moral arguments – namely, the obligation to future generations, for whom local heritage ought to be preserved. As she reminded her audience, “to demolish is the easiest way.”25 She also emphasized the museum’s cultural role: “Conceived in this way, the museum, breaking with previous modes of perception, will become a center adapted to the perception and thinking of modern people.”26 Hankowska additionally highlighted the social dimension, envisioning the possibility of employing retired painters, who would thus have the opportunity to continue designing and painting in the museum. This pro-social, modernizing vision of the museum stands in pointed contrast, in the closing sentence of the aforementioned article, to a consumerist vision – namely, the construction of a service and shopping center. “Is there anything to ponder?” Hankowska asked rhetorically, pointing to the two distinct models of modernization available in the context of Gierek-era Poland’s economic boom: the immediate, consumption-driven model, and the forward-looking, socialized culture program she championed.

The author of the “Fajans” Museum concept contrasts consumption with socialized culture, but not in any narrow sense aimed merely at promoting the culture of state socialism. In another article, “Wzorzec dla Włocławka?” [Model for Włocławek?], published a year later in the same newspaper, Hankowska discusses the English pottery museum in Gladstone, which successfully combines the characteristics of both an industrial and an art museum, while preserving the distinctive visual effects of the ceramic factory architecture. Hankowska proves the popularity of the Gladstone Pottery Museum with the fact that in 1976 it received the National Heritage Museum of the Year award. She concludes by posing the question of whether a similar success might be envisioned for Włocławek.27

In this way, just as faience embodied the typically incompatible categories of art, craft, and commodity, the “Fajans” Museum set for itself the seemingly contradictory goal of promoting the socialist city and its working-class traditions through a model that had proven successful in a capitalist context. Hankowska’s stance and vision thus aligned with the broader model of Gierek-era modernization, which she, however, approached with a critical eye: while embracing the value of opening toward the West, she firmly resisted substituting the fetish of production with the fetish of consumption.

Program

The museum conception that Hankowska sought to promote among decision-makers and the city’s residents was meticulously described by her. Among the documents preserved in the MZKiD archive is a schematic plan of the “Fajans” Museum, which precisely explains its objectives, divided into primary goals of national significance and local goals, unique to Włocławek. The plan also outlines the institution’s structure, describing its various institutes, departments, and the tasks assigned to each. According to it, Hankowska envisioned the Museum as an interdisciplinary institution – not only integrating didactic and exhibitionary functions but also serving diverse communities and specializing in a wide array of knowledge domains (industrial production, materials science, amateur art and craft, and professional art). Yet this heterogeneity did not preclude systematization. Rather, everything was subordinated to, and arose from, the complex process of creating the material object – faience – and the kinds of labor required to bring such an object into existence: the mixing of clay, forming, firing, and painting.

The central aim of this materialist-affective museum was to co-create socialist modernity – in this case, through a substantive engagement with material culture tied to labor traditions and by expanding opportunities for meaningful, qualitative leisure after work. In many respects, this vision represented a continuation of the competencies of the existing regional museum, which, alongside natural history, presented local traditions, occupational types and associated activities, as well as artifacts of material culture produced through everyday life, rituals, and festivities. Importantly, Hankowska did not conceptualize the Museum as an institution solely concerned with the past. Much like contemporary post-industrial museum projects, the “Fajans” Museum was envisioned as an institution actively participating in the co-creation of contemporary culture. Its principal task was to mediate the local community’s engagement with culture and to help generate that culture, grounding it in the region’s rich industrial traditions.

Since its reactivation in 1945, the nationalized faience factory, in collaboration with the regional museum, pursued the vision of mobilizing the creative potential of ordinary people within the realm of industrial design, championed by Wanda Telakowska.28 The factory-produced faience was decorated by women painters, who were actively encouraged to develop their own original designs. By the late 1940s, this creative engagement was further stimulated through workshops conducted by professional artists, and in 1952, the Design Center Number 2 was established at the factory, becoming the second such center founded by the Institute of Industrial Design in Poland.29 In subsequent years, new decoration designs emerged as a result of competitions and, from the 1970s onward, the aforementioned “Fajans” Biennial. The concept of the “Fajans” Museum can thus be understood as a continuation or spinoff of this broader program. The idea of a living museum functioning as a cultural center effectively developed Telakowska’s egalitarian vision of “beauty every day and for everyone” into the museum sphere, positioning the institution as one that would shape tastes and aesthetics through education and collaborative practice, transforming passive recipients of culture into active, generative participants.

If we follow Benoît de L’Estoile’s argument that the history of museology can be read as the history of two fundamental models – the museum of “us” and the museum of the “other”30 – then the museum envisioned by Hankowska was conceived precisely as an institution that dissolved the division between “their” culture and “our” gaze. The “Fajans” Museum was imagined as a space of exchange, open to the everyday. Beyond offering knowledge of production history and the traditions of industrial technology, it was designed to provide a site for artistic practice, learning, and leisure.

In 1981, the factory was formally entered into the register of historical monuments, which was a necessary precondition to launch the project.31 Hankowska wanted to build a museum of socialist modernity upon the ruins of a nineteenth-century factory – yet ironically, by the 1980s, socialist modernity itself was revealing its own condition as ruin.

Documents of Transformation

The corpus of documents relating to the construction of the “Fajans” Museum comprises dozens of items. Organized stacks of folders meticulously chart the successive stages of the project called “Adaptation of the Faience Factory for the ‘Fajans’ Museum in Włocławek.” Among these materials one finds decisions issued by local authorities, conservation reports, a detailed inventory of the factory’s buildings accompanied by extensive photographic documentation, multiple architectural and technical assessments, repeatedly revised architectural plans, contracts between direct and indirect investors as well as with contractors and subcontractors, and a wide range of invoices and correspondence.

From today’s perspective, perhaps the most fascinating item is Construction Log Number 2, which spans the years 1984–1992 and concludes with an entry dated July 12, 1992 – marking the discontinuation of the work. The log offers insights not only into the specific tasks completed during the adaptation efforts in the late 1980s but also into the financial and material difficulties encountered by successive construction firms. The entries record the completion of successive project phases and the exponential cost increases driven by inflation. As such, the document serves as a micro-study of a transforming state, revealing tectonic shifts at every level: within local administrative structures, ownership transitions, and in the broader economic landscape.

Until 1989, the “Fajans” factory continued partial operations on the construction site while simultaneously struggling to build a new production pavilion elsewhere. The construction of the “Fajans” Museum, therefore, unfolded on metaphorical quicksand. The direct investors – the Provincial Directorate for Urban and Rural Development and the Museum of the Kujawy and Dobrzyń Lands – along with numerous limited liability companies created through foreign capital, repeatedly postponed the dates of both the start and completion of construction. Operating across two distinct economic systems, separated by the caesura of 1989, the documents reveal the strain of constant recalibrations, with frequent changes in hourly wage rates and contractors’ requests for additional financial security leaving traces in the archival record.

The construction plan, approved by the Provincial Spatial Planning Office in 1982, included the development of the following facilities: (1) a museum for temporary exhibitions, (2) a kiln and lathe, (3) a kiln, (4) a biscuit warehouse, (5) employee break rooms, (6) tanks, a foundry and paint shops, (7) a warehouse and a kiln, (8) a buffet and ceramics sales point, and (9) an additional warehouse.32 However, the adaptation of none of these was ever completed. The decade-long transformation of the factory into a museum was halted after the roof had been laid, 94 windows purchased, and much of the installation work finished.

However, this was not, to borrow the title of Boris Buden’s book,33 a transition to nowhere. After years of delays and interruptions, the project ultimately culminated in the construction of a shopping mall – a “proxemic metaphor for political transformation.”34 In doing so, the concept debated during public consultations in the 1970s was effectively revisited: namely, the plan to create a service and commercial center on the factory site, conceived as a new urban core. As an afterimage of Gierek-era modernization, the new center offers a space for relaxation in between shopping. In the completed project, some architectural fragments of the old factory were preserved, including elements of the former kiln hall – now housing, among other things, a McDonald’s restaurant.

Industrial Museums and Restructuring: Conferences in 1973 and 1994

The discussions among specialists regarding the “Fajans” Museum in the late socialist and early capitalist periods diverged markedly, reflecting not only different historical moments but also distinct phases in the development of industrial museology.

The first international conference on the conservation of industrial monuments took place in 1973, when the International Committee for the Conservation of the Industrial Heritage (TICCIH) was founded. That same year, an expert meeting was held in Włocławek, reported in a broadcast by Radio PiK titled Ostatni dzwonek [Last Bell].35 Participating in the discussion about the future of the “Fajans” factory and the possibility of establishing a “Fajans” Museum were several prominent figures in the protection of technological and material culture heritage: Professor Jan Pazdur, co-founder of TICCIH and long-time chairman of the Polish National Committee for the Protection of Industrial Heritage; Jerzy Jasiuk, director of the Museum of Technology in Warsaw; Andrzej Michałowski, deputy director of the National Museum in Warsaw and conservator of monuments and green spaces; and Krzysztof Masiak, provincial conservator of monuments. Representing Włocławek were the deputy mayor, the director of the “Fajans” factory, the director of the city’s Department of Construction, Urban Planning, and Architecture, and the director of the Kujawy Museum, Romualda Hankowska.

The discussion centered on a theme that the radio host referred to as industrial archaeology – specifically, “the concept of exhibiting past technology and its connection to the present.” The keynote paper, blending the rhetoric of success propaganda, socialist values, and cautious nods to free-market mechanisms, addressed models of industrial museology, which, it argued, should be organized along lines distinct from those of art museology: “It should finance itself; it should show people at work, and this is already instructive in itself.” In the discussion that followed, participants emphasized that elements of the facility – the “Fajans” factory – held significant documentary value. Another contributor pointed out that the tradition of preserving cultural heritage had, until quite recently, been largely confined to the protection of artistic objects, such as paintings, sculptures, or architecture. Although the tradition of including technological and labor-related facilities in this area was comparatively newer, the “systemic principles” and the educational potential embedded in such structures, they argued, made the protection of industrial heritage imperative. The participants also mentioned the upcoming first international conference on the protection of industrial monuments.

The experts contended that if the production section of the plant could be preserved, it would establish a model for a museum of technical civilization – “a model exemplary in civilized Europe.” French factories, still operating within their original historical buildings and serving as living continuations of past working methods and technologies, were cited as positive reference points. It was further argued that the museum, as a production facility, “should orient itself in the direction of art” – that is, toward the production of artistic ceramics and the comprehensive representation of a tradition understood as an ongoing cultural practice encompassing its productive aspects.

The rhetoric of the 1973 conference alluded to the then-emerging discourse on the protection of labor sites and industrial assets – indeed, the event may be said to have actively participated in shaping that discourse. By contrast, the subsequent conference, held in 1994, was firmly framed within the language of neoliberal transformation, placing the notion of “restructuring” at its center. Organized under the auspices of the Ministry of Industry and Trade, the 1994 conference was dedicated to “seeking methods and means to save the “Fajans” Factory.”36 Its guiding slogan – Revitalization of Technological Monuments: New Life in Historic Industrial Plants – aptly expressed the purpose of the gathering. The call for papers explained that the goal was to address preservation practices concerning monuments of technology and industrial architecture, to evaluate existing adaptation solutions from planning, architectural, social, and economic perspectives, and to comprehensively analyze the legal and financial determinants affecting such efforts. The event was organized by the Center for Monuments Documentation in Warsaw (Expert Team for Architecture, Urbanism, and Cultural Landscape), with its immediate impetus being the bankruptcy of the “Fajans” factory and the bankruptcy trustee’s formal application to remove the site from the register of monuments – a necessary preliminary step toward its demolition. The conference brochure was illustrated with a caricature, depicting a man planting dynamite beneath a building while asking two experts: “Restructure?”

Brochure announcing the conference Revitalization of Industrial Heritage: New Life in Historic Industrial Sites, MZKID Włocławek, 1994. Archival Collection of the Faience Department, MZKiD Włocławek © MZKiD Włocławek

The organizers emphasized that the factory held significant importance for the city’s functioning – serving not only as a place of work but also an art education center. While the stated aim of the conference was to explore potential new uses for the factory, the majority of presentations ultimately focused on analyzing the evolving conditions for the protection of technical monuments in a transforming Poland. As one speaker succinctly summarized, “The goals and forms remain the same; the conditions and opportunities have changed.”37

The new economic circumstances and their impact on the protection of technical monuments were perhaps most accurately encapsulated in a key theme from the introductory paper by Robert Waśkiewicz of the Regional Center for the ”Study and Protection of the Cultural Environment,” titled The Monument as a Component of the Bankruptcy Estate.38 Similarly, Marek Konopka of the Center for Monuments Documentation in Warsaw, in his paper Industrial Objects Can Also Be Monuments: The Essence of Protecting Technical Cultural Heritage, focused on the implications of economic transformation, specifically addressing the following issue: The 1989 Revolution as a Threat to Technical Monuments.39

Other speakers, drawing on case studies from France, Great Britain, and Germany, examined the practice of adapting industrial sites within the framework of European legislation, and explored the new functions assigned to cultural monuments – including landscape parks, museums, and commercial infrastructure. Several papers also addressed the social situation in Włocławek. Reinhard Coppenrath (Osnabrück) compared the symbolic emptiness of the abandoned “Fajans” factory to the situation of Włocławek’s residents.40 Ultimately, however, the various revitalization models and post-industrial reuse strategies presented by museum professionals and urban planners were largely inapplicable to the “Fajans” factory due to severe budgetary limitations and the city’s deteriorating social conditions. As a result, the concept of adapting the historic factory buildings – as proposed by the Head of the Faience Department at the MZKiD Janina Dobrowolska – was no longer framed within the ambitious cultural discourse of the 1970s, which had imagined the creation of a museum of European stature. Instead, the proposal was recast as a response to local social crises – particularly poverty and unemployment – stemming from the disappearance of nearly all existing jobs in Włocławek. The title of Dobrowolska’s presentation was telling: The Twilight of the Adaptation of the Factory on Kościuszko Street into the “Fajans” Museum.

As noted at the outset of this text, the reasons behind the “twilight of adaptation” are clear. The failure of the project to establish the “Fajans” Museum was not only the result of the transformation of the state system and the accompanying economic upheaval, but also a consequence of the very ideology underpinning that transformation. The museum had been envisioned as a model product of socialism, and as such, it embodied values that, in the new era, were deemed obsolete. Yet the teleological vision of transformation – particularly dominant in the first years after 1989 – has, over time, yielded to a more critical perspective, one that not only questions the terms of capitalist modernization but also revisits the alternate paths, possibilities, and imagined futures that once existed. As Beáta Hock observes, “more recent academic discussions of East-Central Europe’s ‘long transformation’ attempt to move away from a certain teleological approach that would suggest that developments after 1989 pointed towards a singular known end: the ‘normalization’ of ex-Eastern Bloc economies and politics according to Western (European) models, i.e. capitalism and democracy.”41 Within this framework, the archive of the “Fajans” Museum – which is also, fundamentally, an archive of the debates over competing visions of contemporary culture – emerges as a material resource enabling work on the potentialities of the transition period.

Women’s Labor Museum

In his discussion of uncreated museums in Warsaw, Łukasz Bukowiecki introduces the concept of “museums-pretexts” and the notion of negative heritage.42 He interprets the conceptions behind these museums as fundamentally rescue-oriented projects, designed primarily to protect the material fabric of the historic buildings. As he writes, these museums were conceived “to manage and transform the buildings where they would be located – in the face of current threats to them and because of the historical and/or artistic value attributed to them.”43

To some extent, the “Fajans” Museum project can indeed be situated within this framework of preservation policy – specifically, the preservation of industrial heritage. However, as I have sought to demonstrate, the purpose behind its creation extended beyond the rescuing of historic factory buildings; at its core, the project was intended to protect the heritage of labor culture and workers’ creativity. In this sense, it is not so much about negative heritage as theorized by Lynn Meskell,44 but rather constitutes what might be called an abandoned or potential heritage of socialism.

The “Fajans” Museum in Włocławek is not the only museum institution whose establishment was thwarted by political and economic shifts.45 However, in this case, we are also confronting the disintegration of the very community the museum was intended to serve. First, Włocławek underwent a transformation during the period of systemic transition and deindustrialization, shifting from an industrial and immigrant city to one marked by unemployment and emigration. Second, the painters and other workers associated with the “Fajans” factory did not constitute as visible or cohesive a professional group as, for example, miners or textile workers. Post-industrial museums – and from today’s vantage point, the “Fajans” Museum would be situated within this category – have typically been understood as institutions that help to sustain and develop the identity of local working communities in the aftermath of industrial decline. This phenomenon has been particularly associated with the aforementioned occupational groups. Yet, in a sense, the disappearance and transformation of such communities are part of the broader dynamics that shape all museums.

In her publication Metabolic Museum, which addresses the decolonization process of Frankfurt’s ethnographic museum, Clémentine Deliss reflects on the extent to which many existing collections and museum institutions today have lost their social legitimacy. Deliss draws attention not only to the obvious – namely, colonial collections – but also to national or nationalist and folklore collections, which, in her view, “are becoming redundant as reflectors of urban-rural identities in today’s world.”46 Faced with this erosion of social legitimacy, instead of producing expert knowledge about appropriated and decontextualized objects, Deliss advocates for creative and collective engagement with collections – working on their visual discourse and probing the relationships between the objects and processes of knowledge production, as well as between the objects and bodies in the museum. This is a practice she describes as “fieldwork in the museum,”47 which does not treat the information gathered merely as data, but as material for building relationships and forging new communities around the collection.

Such an approach offers a promising framework for working with the “Fajans” Museum’s archive – through speculative engagement with its history and the virtual activation of its unrealized potential.

Imagined museums, such as the virtual feminist museum proposed by Griselda Pollock,48 have emerged as critical tools within art history, offering alternatives to institutional models built on exclusion and physical constraint. The critical potential of the non-existent “Fajans” Museum lies precisely in the fact that, as a project seen from the future, it unsettles a teleological vision of political transformation. In this context, it is worth recalling Ariella Azoulay’s observation that “potential history is an effort to make history impossible and to engage with the world from a nonprogressive approach.”49

So what might the “Fajans” Museum, envisioned through Romualda Hankowska’s concept and reactivated through the archives, have become today? From a contemporary perspective, the “Fajans” Museum primarily tells the story of professional emancipation under socialism and the formation of a women’s professional community – offering a foundation for the creation of a new kind of cultural institution. Conceived as a Museum of Women’s Labor, it would illuminate both the collective identity and the individual stories of the women painters and experts who shaped the practice, discourse, and infrastructure of “Fajans” production. The work and creativity of these women – both painters and organizers – would be interpreted through perspectives that eschew hierarchical distinctions between categories of knowledge, instead valuing collective skills, practices, and embodied expertise. As such, the museum would emerge as an institution actively participating in the re-evaluation of Poland’s histories of emancipation – a task which, as Agnieszka Mrozik notes, entails “reminding us of the multiplicity of concepts and ways of realizing emancipation projects.”50

On the one hand, the “Fajans” Museum would be a museum of artistic practices and of the intersections between factory labor and the artistic activation of so-called ordinary people, particularly women. “Fajans” was a gendered product – created by women and largely for women. Its distinctive value stemmed from the fact that women painters employed at the factory decorated it with designs of their own creation. During the socialist period, their labor and contributions to both the factory and the city were publicly recognized. The painters were honored, photographed, and rendered visible. Their names appeared not only on captions accompanying photographic documentation, diplomas, and awards, but also on the decorated vessels themselves.

The most talented among them, serving as master painters, became part of the city’s local elite, appearing at official ceremonies alongside political figures. They traveled abroad to faience exhibitions, where they demonstrated traditional techniques of hand-painting ceramics. Testimonies from the painters themselves indicate that they experienced a sense of visibility, empowerment, and recognition.51 This affirmative narrative constitutes one of two narrative threads presented within the museum.

The “Fajans” Museum should also be understood as an institution that interrogates and reflects on the processes of economic exclusion in a functioning parliamentary democracy. In this sense, the “Fajans” Museum would also be a museum of women’s unemployment and exclusion from the labor market during the post-socialist transition – as exemplified by the fate of the “Fajans” painters. As social historians and sociologists have underscored, the transition was gendered, with women emerging as its greatest casualties.52 It was not only the 1993 legislation that sharply curtailed women’s reproductive rights; women also lost their positions and privileges as workers, becoming relegated to unpaid care work and affective labor – the so-called invisible labor.53

Analyzing the situation of women in the labor market after 1989, Izabela Desperak raises critical questions about the extent to which the political practices of the transformation period fulfilled the theoretical criteria of democratization – particularly when examined through the lens of the right to work. Desperak draws on theories that explain gendered inequalities in the labor market, including Veronica Beechey’s reserve army of labor theory, which positions women’s wage labor as a source of cheap and flexible labor, and Sheila Rowbotham’s patriarchal-capitalism theory, later developed by Heidi Hartmann, which locates the roots of women’s social disadvantage within the very structure of capitalism and the interdependence of capitalist and patriarchal systems.54 Desperak emphasizes that in analyzing and historicizing the Polish transition, the patriarchal-capitalist framework is particularly instructive, as it helps to explain “the increase in the intensity of patriarchalism in Polish society after 1989 as a result of the restoration of capitalism following a period when the economy was shaped by the paradigm of real socialism.”55

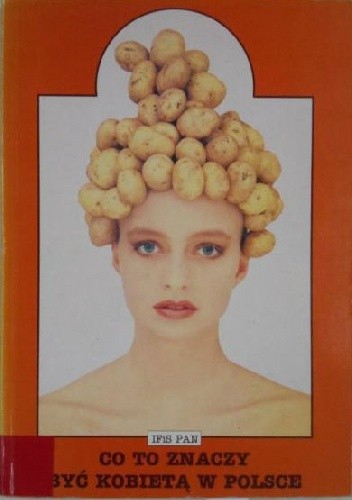

Cover of the collective volume What It Means to Be a Woman in Poland, edited by Anna Titkow and Henryk Domański, Warsaw, 1995

The occupational situation of the faience painters during the transformation period was emblematic of broader patterns affecting other women’s professional groups.56 A 1995 collective volume, Co to znaczy być kobietą w Polsce [What It Means to Be a Woman in Poland], edited by Anna Titkow and Henryk Domański, documents numerous similar cases, employing standardized terms such as “factory bankruptcy” and “mass layoffs,” alongside the euphemistic phrase “restrictive economic policy” to characterize the situation. In this context, the “Fajans” Museum could serve as a site for narrating the gendered dimensions of the experience of “economic restructuring” during the transition. It could trace the career trajectories of the women painters following the factory’s closure and explore the reevaluations that reshaped both their social standing and the status of the objects they once created. In doing so, the museum would offer an alternative, critical discourse on the visibility of “Fajans” herstory.

Translated by Karol Waniek

This research was funded in whole by National Science Centre, Poland. Grant number 2022/47/D/HS2/00446

Bibliography

Azoulay, Ariella Aïsha. Potential History: Unlearning Imperialism. London: Verso, 2019.

Bandziak-Kwiatkowska, Karolina. “Archiwum po Wzorcowni Fabryki Fajansu w Muzeum Ziemi Kujawskiej i Dobrzyńskiej we Włocławku.” Rocznik Muzealny MZKiD we Włocławku (Włocławek, 2012): 7–18.

Bogdan, Cristina, and Piotr Sikora. “The End of the End (of Post Communism). In Conversation with Boris Buden.” http://blokmagazine.com/the-end-of-the-end-of-post-communism-in-conversation-with-boris-buden/.

Buden, Boris. Transition to Nowhere: Art in History after 1989. Berlin: Archive Books, 2020.

Bukowiecki, Łukasz. Muzea-preteksty: Niezrealizowane przedsięwzięcia muzealne wobec negatywnego dziedzictwa w Warszawie. Warsaw: Wydawnictwo Uniwersytetu Warszawskiego, 2021.

Dąbrowski, Jacek. “Dziedzictwo przemysłu — dziedzictwo niechciane — dziedzictwo nieznane.” Protection of Cultural Heritage, March 2017. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/342583346_DZIEDZICTWO_PRZEMYSLU_-_DZIEDZICTWO_NIECHCIANE_-_DZIEDZICTWO_NIEZNANE.

Deliss, Clémentine. The Metabolic Museum. Berlin: Hatje Cantz, 2022.

Desperak, Izabela. Płeć zmiany: Zjawisko transformacji w Polsce z perspektywy gender. Łódź: Wydawnictwo Uniwersytetu Łódzkiego, 2013.

Domański, Henryk, and Anna Titkow, eds. Co to znaczy być kobietą w Polsce. Warsaw: Wydawnictwo IFiS PAN, 1995.

de L’Estoile, Benoît. Le Goût des Autres: De l’Exposition coloniale aux Art premiers. Paris: Flammarion, 2007. Quoted in Pablo Lafuente, “Introduction: From the Outside In — ‘Magiciens de la Terre’ and Two Histories of Exhibitions.” https://www.afterall.org/articles/introduction-from-the-outside-in-magiciens-de-la-terre-and-two-histories-of-exhibitions/#footnote-reference-3-1-5f49

Fuszara, Małgorzata, and Monika Tarnowska. “Kobiety – kategoria ‘szczególnie chronionych pracowników’?” In Co to znaczy być kobietą w Polsce, edited by Henryk Domański and Anna Titkow, 119–134. Warsaw: Wydawnictwo IFiS PAN, 1995.

Hankowska, Romualda. Fajans włocławski. Wrocław: Ossolineum, 1991.

Hartman, Saidiya. Wayward Lives: Beautiful Experiments, Intimate Histories of Riotous Black Girls, Troublesome Women, and Queer Radicals. London: Profile Books, 2021.

Hock, Beáta. “Evolving Networks: International Sponsors of Post-Socialist Art Scenes.” Journal of Contemporary Central and Eastern Europe 31, no. 1 (2023).

Huml, Irena. “Fajans włocławski.” Projekt 1959, no. 1 (15): 16–18.

Klekot, Ewa. Kłopoty ze sztuką ludową. Gdańsk: Słowo/Obraz Terytoria, 2021.

Kordjak, Joanna. “Polska – kraj folkloru? Wstęp.” In Polska. Kraj folkloru?, edited by Joanna Kordjak, 11–40. Warsaw: Zachęta Narodowa Galeria Sztuki, 2016.

Korduba, Piotr. Ludowość na sprzedaż: Towarzystwo Popierania Przemysłu Ludowego, Cepelia, Instytut Wzornictwa Przemysłowego. Warsaw: Fundacja Bęc Zmiana and Narodowe Centrum Nauki, 2013.

Lafuente, Pablo. “Introduction: From the Outside In – ‘Magiciens de la Terre’ and Two Histories of Exhibitions.” Afterall (online). https://www.afterall.org/articles/introduction-from-the-outside-in-magiciens-de-la-terre-and-two-histories-of-exhibitions/

Leyk, Aleksandra, and Joanna Wawrzyniak. Cięcia: Mówiona historia transformacji. Warsaw: Wydawnictwo Krytyki Politycznej, 2020.

Majewska-Güde, Karolina. “Telling Stories about Feminist Art in Socialist Europe. Or the Archive as a Place of Cross-Generational Remaking.” Miejsce 2021, no. 7. https://miejsce.asp.waw.pl/en/telling-stories-about-feminist-art-in-socialist-europe-or-the-archive-as-a-place-of-cross-generational-remaking/.

Meskell, Lynn. “Negative Heritage and Past Mastering in Archaeology.” Anthropological Quarterly 75, no. 3 (2002): 557–57.

Mrozik, Agnieszka. Akuszerki transformacji: Kobiety, literatura i władza w Polsce po 1989 roku. Warsaw: Wydawnictwo IBL PAN, 2012.

Pisarska, Barbara. “Rola wypoczynku socjalnego w Polsce podczas dekady 1970–1980 w świetle literatury.” In Dekada Gierka. Wnioski dla obecnego okresu modernizacji Polski, edited by Krzysztof Rybiński, 177–192. Warsaw: Uczelnia Vistula, 2011.

Pisarska, Barbara. “Rozwój turystyki w Polsce w dekadzie 1970 i jego uwarunkowania.” In Dekada Gierka. Wnioski dla obecnego okresu modernizacji Polski, edited by Krzysztof Rybiński, 193–207. Warsaw: Uczelnia Vistula, 2011.

Pollock, Griselda. Encounters in the Virtual Feminist Museum: Time, Space and the Archive. New York and London: Routledge, 2007.

Preda, Caterina. Art and Politics Under Modern Dictatorships: A Comparison of Chile and Romania. New York: Palgrave, 2017.

Sasse, Sylvia and Kata Krasznahorkai(eds.) Artists & Agents: Performance Art and Secret Services, Leipzig: Spector Books, 2020.

Telakowska, Wanda. Twórczość ludowa w nowoczesnym wzornictwie. Warsaw: Wydawnictwo Sztuka, 1954.

Traumane, Mara. “Instructive, Dramatic, and Corrective Collectivity: Socialist Realism in the Mirror of Collegial Debates. A Case Study of Documents of the Artists’ Union of the Latvian Soviet Socialist Republic, 1944–55.” ARTMargins 8, no. 1 (2019).

Zaremba, Łukasz, Obrazy wychodzą na ulice: Spory w polskiej kulturze wizualnej. Warsaw: Fundacja Bęc Zmiana, Instytut Kultury Polskiej UW, 2018.

- The “bulldozer exhibition,” which became a symbol of the dissident art scene in the Soviet Union, took place on September 15, 1974, in the Belyayevo suburb of Moscow and was cleared by the militia and bulldozers. ↩︎

- Kronika Fabryki Fajansu [Chronicle of the Faience Factory], directed by Andrzej Papuziński, Wytwórnia Filmów Oświatowych, 1974. ↩︎

- Łukasz Zaremba, Obrazy wychodzą na ulice: Spory w polskiej kulturze wizualnej [Images Take to the Streets: Disputes in Polish Visual Culture] (Warsaw: Fundacja Bęc Zmiana, Instytut Kultury Polskiej UW, 2018). ↩︎

- On the notion of folk art, see Ewa Klekot, Kłopoty ze sztuką ludową [The Trouble with Folk Art] (Gdańsk: Słowo/Obraz Terytoria, 2021); Joanna Kordjak, “Polska – kraj folkloru? Wstęp” [“Poland – A Country of Folklore? Introduction”] in Polska. Kraj folkloru?, edited by Joanna Kordjak (Warsaw: Zachęta Narodowa Galeria Sztuki, 2016), 11–40; Piotr Korduba, Ludowość na sprzedaż: Towarzystwo Popierania Przemysłu Ludowego, Cepelia, Instytut Wzornictwa Przemysłowego [Folkness for Sale: The Society for the Promotion of Folk Industry, Cepelia, Institute of Industrial Design] (Warsaw: Fundacja Bęc Zmiana and Narodowe Centrum Nauki, 2013). ↩︎

- See, for example, Aleksandra Leyk and Joanna Wawrzyniak, Cięcia: Mówiona historia transformacji [Cuts: An Oral History of Transformation] (Warsaw: Wydawnictwo Krytyki Politycznej, 2020). ↩︎

- Ariella Aïsha Azoulay, Potential History: Unlearning Imperialism (London: Verso, 2019), 286. ↩︎

- Saidiya Hartman, Wayward Lives: Beautiful Experiments, Intimate Histories of Riotous Black Girls, Troublesome Women, and Queer Radicals (London: Profile Books, 2021). ↩︎

- Joan Wallach Scott, The Fantasy of Feminist History (Durham: Duke University Press, 2011). ↩︎

- Until recently, the study of official archives from the socialist period in regional art history was not associated with a revisionist perspective. Sometimes art historians used archival materials creatively, as in the publication Artists & Agents: Performance Art and Secret Services, in which the archives of the secret services were interpreted as an alternative form of performance art documentation (see Artists & Agents: Performance Art and Secret Services, edited by Sylvia Sasse and Kata Krasznahorkai [Leipzig: Spector Books, 2020]). The exploration of state archives is an important part of research on socialist internationalism or transnational and transregional art history (see Caterina Preda, Art and Politics Under Modern Dictatorships: A Comparison of Chile and Romania [New York: Palgrave, 2017]). Researchers also turn to the archives of artistic unions to nuance the image of official art in socialist Europe (see Mara Traumane, “Instructive, Dramatic, and Corrective Collectivity: Socialist Realism in the Mirror of Collegial Debates. A Case Study of Documents of the Artists’ Union of the Latvian Soviet Socialist Republic, 1944–55,” ARTMargins 8, no. 1 [2019]). ↩︎

- The project received, among others, the Grand Prix in the “Budowa na Medal Pomorza i Kujaw 2009” competition in the category of “modernized” buildings under conservation protection, as well as a first-degree award in the “Najlepsza inwestycja 2009” competition. ↩︎

- Paper Loss, Feelings, and Care in the Reception of Ancient Greece and Rome, presented at the conference Lost and Found in Lisbon in 2023. The conference focused on the question of what has been lost through the modernist reduction of art to its aesthetic function. ↩︎

- See Karolina Majewska-Güde, “Telling Stories about Feminist Art in Socialist Europe. Or the Archive as a Place of Cross-Generational Remaking,” Miejsce 2021, no. 7, https://miejsce.asp.waw.pl/en/telling-stories-about-feminist-art-in-socialist-europe-or-the-archive-as-a-place-of-cross-generational-remaking/ (accessed November 13, 2024). ↩︎

- The relocation of the factory was determined in a decision on the city’s general development plan, adopted by the National Council in 1963, followed by (1969) the adaptation of the factory into the city’s new central hub. The first nationwide competition for the adaptation design was organized in 1969. ↩︎

- Anna Jachnina, Fajansowe problemy [Faience Problems], Radio PiK broadcast, November 8, 1963, 00:14:23. ↩︎

- Zapiski do historii Partii z okresu międzywojennego działalności Przemysłu Metalowego we Włocławku. Rozpoczęto 7.02.1948. Zakończono 23.05.1948 [Notes on the History of the Party from the Interwar Period of the Metal Industry in Włocławek. Started February 7, 1948. Completed May 23, 1948] Archival Collection of the Faience Department, Museum of the Kujawy and Dobrzyń Land in Włocławek. ↩︎

- (rk), “We Włocławku powstanie Muzeum Fajansu” [“A Faience Museum Will Be Established in Włocławek”], Alchemik: Pismo Samorządów Robotniczych ZAW »Lakierów« i »Korchemu«, June 1–15, 1975, Archival Collection of the Faience Department, Museum of the Kujawy and Dobrzyń Land in Włocławek. ↩︎

- Alchemik: Pismo Samorządów Robotniczych ZAW »Lakierów« i »Korchemu«. ↩︎

- Romualda Hankowska, Fajans włocławski [Włocławek Faience] (Wrocław: Ossolineum, 1991). ↩︎

- See Irena Huml, “Fajans włocławski” [“Włocławek Faience”],Projekt 1959, no. 1 (15): 16–18. ↩︎

- Anna Jachnina was an editor at Radio PiK and the author of numerous radio programs, including on Włocławek faience. She documented folk art and culture, to which she devoted over 300 radio broadcasts. See https://archiwum.radiopik.pl/ ↩︎

- Wanda Telakowska, Twórczość ludowa w nowoczesnym wzornictwie [Folk Art in Modern Design] (Warsaw: Wydawnictwo Sztuka, 1954). ↩︎

- “Żywe Muzeum Fajansu” [“Living Museum of Faience”],Gromada. Rolnik Polski, June 13, 1974, Archival Collection of the Faience Department, Museum of the Kujawy and Dobrzyń Land in Włocławek. ↩︎

- Romualda Hankowska, “Fabryka-Muzeum” [“Factory-Museum”] Kurier Ilustrowany, May 17–18, 1975, Archival Collection of the Faience Department, Museum of the Kujawy and Dobrzyń Land in Włocławek. ↩︎

- Barbara Pisarska, “Rola wypoczynku socjalnego w Polsce podczas dekady 1970–1980 w świetle literatury” [“The Role of Social Recreation in Poland During the 1970–1980 Decade in the Light of the Literature”] in Dekada Gierka. Wnioski dla obecnego okresu modernizacji Polski [The Gierek Decade: Lessons for the Current Period of Poland’s Modernization], edited by Krzysztof Rybiński, 177–192 (Warsaw: Uczelnia Vistula, 2011), 178. See also in the same volume: Barbara Pisarska, “Rozwój turystyki w Polsce w dekadzie 1970 i jego uwarunkowania” [“The Development of Tourism in Poland in the 1970s and Its Determinants”], 193–207. ↩︎

- Hankowska, “Fabryka-Muzeum.” ↩︎

- Ibid. ↩︎

- Romualda Hankowska, “Wzorzec dla Włocławka?” [“Model for Włocławek?”],Kurier Ilustrowany, October 23–24, 1976, Archival Collection of the Faience Department, Museum of the Kujawy and Dobrzyń Land in Włocławek. ↩︎

- Telakowska, Twórczość ludowa, 1954. ↩︎

- See Karolina Bandziak-Kwiatkowska, “Archiwum po Wzorcowni Fabryki Fajansu w Muzeum Ziemi Kujawskiej i Dobrzyńskiej we Włocławku” [“The Archive of the Faience Factory Pattern Shop at the Museum of the Kujawy and Dobrzyń Land in Włocławek”] Rocznik Muzealny MZKiD we Włocławku (Włocławek, 2012), 7–18. ↩︎

- Benoît de L’Estoile, Le Goût des Autres: De l’Exposition coloniale aux Art premiers (Paris: Flammarion, 2007), 12–13. Quoted in Pablo Lafuente, “Introduction: From the Outside In — ‘Magiciens de la Terre’ and Two Histories of Exhibitions,” https://www.afterall.org/articles/introduction-from-the-outside-in-magiciens-de-la-terre-and-two-histories-of-exhibitions/#footnote-reference-3-1-5f49 (accessed November 8, 2024). ↩︎

- As Jacek Dąbrowski reports, “The factory complex was entered into the register of monuments in 1981 with the following justification: It is the only factory producing hand-painted faience. It has significant value due to the preservation of many buildings and machines from the second half of the 19th century, which today have value as technical monuments […]. In the decision, 12 objects within the factory complex were listed as particularly valuable, while the entire faience factory complex then included over 60 (!) historic objects. Plans to establish a Faience Museum on the grounds of the former plant came to nothing, and the entire factory complex passed into private hands. In 2002, the Ministry of Culture and National Heritage – at the owner’s request – removed eight of the objects from the register of monuments. Of the entire complex of over 60 objects, only one survived – the former pattern shop building, which after renovation became part of a newly created commercial-residential-service complex called Centrum ‘Wzorcownia’.” See Jacek Dąbrowski, “Dziedzictwo przemysłu – dziedzictwo niechciane – dziedzictwo nieznane” [“Industrial Heritage – Unwanted Heritage – Unknown Heritage] Protection of Cultural Heritage, March 2017, 154, https://www.researchgate.net/publication/342583346_DZIEDZICTWO_PRZEMYSLU_-_DZIEDZICTWO_NIECHCIANE_-_DZIEDZICTWO_NIEZNANE. ↩︎

- Plan for the construction of the Museum of Faience, approved in 1982 by the Provincial Office for Spatial Planning. Archival Collection of the Faience Department, Museum of the Kujawy and Dobrzyń Land in Włocławek. ↩︎

- Reference to the title of Boris Buden’s book Transition to Nowhere: Art in History after 1989 (Berlin: Archive Books, 2020). Boris Buden explains his perspective: “My point is that this emancipatory promise, the capacity of democracy to move forward on all levels and make something live, make it better, has been exhausted. Masses no longer believe that we have to work ten years more and then we will be like… the British or the German? This so-called Western democracy is no longer something you can take as a role model, and that is part of the problem.” Cristina Bogdan and Piotr Sikora, “The End of the End (of Post Communism). In Conversation with Boris Buden,” http://blokmagazine.com/the-end-of-the-end-of-post-communism-in-conversation-with-boris-buden/ (accessed November 8, 2024). ↩︎

- Izabela Desperak, Płeć zmiany: Zjawisko transformacji w Polsce z perspektywy gender (Łódź: Wydawnictwo Uniwersytetu Łódzkiego, 2013), 122. Desperak writes: “A proxemic metaphor of transformation is the supermarket, the shopping center, and its successor: the shopping ‘gallery’, whose name suggests an object of high culture – it is precisely such ‘galleries’ that mark new city centers and transform them beyond recognition. It is these ‘galleries’ that residents are proud of, although standardization makes us unaware whether we are in Budapest, Krakow, or perhaps the outskirts of a provincial town. However, alongside supermarkets and ‘galleries’ designed for the aspiring middle class, Polish women shop elsewhere altogether.” ↩︎

- Anna Jachnina, Ostatni dzwonek [Last Bell], Radio PiK broadcast, December 31, 1973, 00:13:46. ↩︎

- Brochure with the program of the conference Rewitalizacja zabytków techniki. Nowe życie w zabytkowych zakładach przemysłowych (Revitalization of Technological Monuments: New Life in Historic Industrial Plants), organized under the patronage of the Ministry of Industry and Trade, 1994. Archival Collection of the Faience Department, Museum of the Kujawy and Dobrzyń Land in Włocławek. ↩︎

- Typescripts of paper abstracts. Archival Collection of the Faience Department, Museum of the Kujawy and Dobrzyń Land in Włocławek. ↩︎

- Ibid. ↩︎

- Ibid. ↩︎

- Ibid. ↩︎

- Beáta Hock, “Evolving Networks: International Sponsors of Post-Socialist Art Scenes,” Journal of Contemporary Central and Eastern Europe 31, no. 1 (2023): 95–108, 104. ↩︎

- Łukasz Bukowiecki, Muzea-preteksty: Niezrealizowane przedsięwzięcia muzealne wobec negatywnego dziedzictwa w Warszawie (Warsaw: Wydawnictwo Uniwersytetu Warszawskiego, 2021). ↩︎

- Ibid., 17. ↩︎

- Bukowiecki also refers to Lynn Meskell’s concept of negative heritage. See Lynn Meskell, “Negative Heritage and Past Mastering in Archaeology,” Anthropological Quarterly 75, no. 3 (2002): 557–57. ↩︎

- Another example is the Museum of Modern Art in Koszalin. ↩︎

- Clémentine Deliss, The Metabolic Museum (Berlin: Hatje Cantz, 2022), 48. ↩︎

- Ibid. ↩︎

- Griselda Pollock, Encounters in the Virtual Feminist Museum: Time, Space and the Archive (New York–London: Routledge, 2007). ↩︎

- Ariella Aïsha Azoulay, Potential History, 269. ↩︎

- Agnieszka Mrozik, Akuszerki transformacji, 13. ↩︎

- Statements from women painters in archival Radio PiK broadcasts were used in the film Lubi pani swoją pracę? Malowany fajans włocławski (Do You Like Your Job? Painted Faience from Włocławek), produced in 2024 by the Museum of the Kujawy and Dobrzyń Land based on archival research by Karolina Bandziak-Kwiatkowska, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=MwnEiY4_A3U (accessed November 8, 2024). ↩︎

- See Izabela Desperak, Płeć zmiany. ↩︎

- Even during socialism, while holding a double professional and domestic workload, women carried out most caregiving and reproductive tasks, which was reflected in labor law: caregiving leaves only for women; bans on working in certain occupations. See Małgorzata Fuszara and Monika Tarnowska, “Kobiety – kategoria ‘szczególnie chronionych pracowników’?” (“Women – A Category of ‘Specially Protected Workers’?”) in Co to znaczy być kobietą w Polsce (What It Means to Be a Woman in Poland), edited by Henryk Domański and Anna Titkow (Warsaw: Wydawnictwo IFiS PAN, 1995), 119–134. ↩︎

- Izabela Desperak, Płeć zmiany, 53 ↩︎

- Ibid. ↩︎

- In 1995, Krystyna Janicka wrote about the occupational segregation of women and men, stating that “in times of austerity or recession, which in practice means rising unemployment and competitiveness, as we have experienced in Poland since the early 1990s, it is primarily women who are laid off or demoted.” Krystyna Janicka, “Kobiety i mężczyźni w strukturze społeczno-zawodowej: podobieństwa i różnice” (“Women and Men in the Social and Professional Structure: Similarities and Differences”), in Co to znaczy być kobietą w Polsce, 89–118, 91. ↩︎

Karolina Majewska-Güde

Karolina Majewska-Güde, PhD, is a researcher, art historian, and curator. Her research focuses on the East Central European neo-avant-gardes, feminist epistemologies, performance art, and contemporary issues of circulation, translation, and knowledge-production through art-based research. She is a member of the research collective pisze/mówi/robi, which combines performative and interpretative research on artistic archives. Her recent book Ewa Partum’s Artistic Practice: An Atlas of Continuity in Different Locations was published by Transcript in 2021.