Title

Permanent Transience Muzeum Sztuki in Łódź under Jaromir Jedliński (1991–1996)

https://doi.org/10.48285/ASPWAW.29564158.MCE.2024.10.10EN

Muzeum Sztuki w Łodzi, Jaromir Jedliński, Ryszard Stanisławski, neoliberalism, post-communist transformation

https://miejsce.asp.waw.pl/en/permanentna-tymczasowosc/

Abstract

This article undertakes to analyze the functioning of Muzeum Sztuki (Museum of Art) in Łódź during the period of political transformation. Focusing on the directorship of Jaromir Jedliński, it seeks to reconstruct his strategies and actions in response to the profound political, economic, and institutional shifts that reshaped the museum landscape after 1989. The text highlights the persistent underfunding, the absence of a stable legal framework, and internal tensions within the museum community. Particular emphasis is placed on Jedliński’s attempts to align the museum’s operations with the emerging system of cultural financing, all while contending with the enduring legacy of Ryszard Stanisławski. Drawing on archival materials and contemporaneous press accounts, the article presents Jedliński’s tenure not merely as a series of individual decisions, but more crucially, as a manifestation of broader systemic processes linked to the post-socialist transition.

Keywords

Muzeum Sztuki w Łodzi, Jaromir Jedliński, Ryszard Stanisławski, neoliberalism, post-communist transformation

DOI

Two Ends. Introduction

The year 1991 at Muzeum Sztuki in Łódź marked the confluence of two significant ends. On the macro level, it signaled the demise of the socialist model of state-funded culture. On the micro level, it coincided with the departure of Ryszard Stanisławski from his position as director after a twenty-five-year tenure. This transition was marked by an exhibition celebrating the 60th anniversary of the collection of Muzeum Sztuki, which opened at Warsaw’s Zachęta Gallery in May 1991. Organized with considerable panache, the exhibition not only served as a crowning tribute to Stanisławski’s achievements but also implicitly questioned the future role of Muzeum Sztuki within the reconfigured institutional landscape emerging in Poland after 1989.

The 20th-Century Art Collection at the Muzeum Sztuki in Łódź. Exhibition Marking the 60th Anniversary of the Łódź Collection of Modern Art, Zachęta – National Gallery of Art, Warsaw, 1991. Photo: Archives of the Muzeum Sztuki in Łódź.

This article seeks to analyze the activities of Muzeum Sztuki during the directorship of Jaromir Jedliński, spanning the years 1991 to 1996. Jedliński joined the institution in 1980, immediately after completing his art history studies at Adam Mickiewicz University in Poznań. As a young curator, he became part of one of the leading cultural institutions in Poland – central both to the domestic art scene and to the international promotion of Polish art. He quickly became a close associate of Stanisławski, who saw in the younger generation of curators (including Maria Morzuch) an opportunity to revitalize the museum’s international program. Initially employed in the Department of Graphics and Modern Drawing, Jedliński soon took charge of several key exhibitions of the period, including Polentransport (1981), Realizm społeczny pop-artu [Pop Art’s Social Realism], and a monographic exhibition of Michael Kidner. These responsibilities suggest that Stanisławski may have regarded Jedliński as his successor, possibly even preparing him for the role. In mid-1991, the succession was realized. Jedliński’s appointment occurred without a formal competition, although it is important to note that such a procedure was not legally required at the time. The decision to dispense with an open recruitment process may have been influenced by Stanisławski’s support, and it undoubtedly expedited the transition – a factor of some significance in the circumstances of the period.

The appointment of a long-standing employee of the Museum and close associate of Stanisławski appears to have been a strategic move aimed at ensuring the institution’s stable passage through a time of considerable uncertainty. Based on extant documentation, it may be inferred that Jedliński supported the postulate of “liberating the market” in the cultural sphere (e.g. by the introduction of private sources of funding), but he does not appear to have fully grasped the practical implications of such a shift for the institution under his leadership. Undeniably, he perceived this fundamental transformation as an opportunity to develop a new organizational and managerial model. At the same time, it seems he did not fully comprehend the disquiet within the Museum’s staff, which resulted from the institution’s worsening economic and social circumstances. One might surmise that his principal concern was to preserve the Museum’s stature and artistic standing, which necessarily involved living up to the legacy of Ryszard Stanisławski.

Capturing this tension – between the broader systemic transformation and the internal transition into a new era of institutional leadership – is the central objective of this article. This is a largely overlooked chapter in the institutional history of Muzeum Sztuki in Łódź. As such, the article is grounded in foundational research and constitutes a preliminary inquiry into the issues outlined here. The analysis is based on archival materials from the Departmental Archives of Muzeum Sztuki in Łódź, primarily administrative records and correspondence, as well as on an examination of the media discourse surrounding the Museum.1 The historical context is shaped by the broader impact of systemic transformation on cultural institutions.

Local Government Museum

The impact of systemic transformation on cultural institutions is by now a relatively well-explored subject.2 Both studies from the 1990s and more recent scholarship concur that the trajectory of the transformation in the cultural sphere was marked as much by “shock” as by disarray. From the decision-makers’ perspective, culture was perhaps the least significant domain of the newly transforming state, rendered more an object than an active subject of transformation. This is exemplified most clearly by the fact that between 1989 and 1999, the office of the Minister of Culture was occupied by no fewer than nine individuals.3 Both post-Solidarity and post-communist administrations adhered to the maxim that “the best cultural policy is no cultural policy.”4 The principal objective became the alignment of the cultural sector with the two major reforms initiated after 1989: public finance reform (the so-called Balcerowicz Plan) and local government reform. For cultural institutions, this translated into a drastic reduction in public funding and, in accordance with the tenets of the emerging neoliberal doctrine, the “restructuring” of institutions and “optimization” of employment.5

At the same time, in 1990, the Ministry of Culture and Art introduced a new administrative and – by extension – financial framework for the cultural sector, delineating three levels of institutional governance: national, state, and local government.6 Institutions deemed of paramount importance to Polish culture were to be classified at the national level and thus fully financed by the Ministry, ensuring relative budgetary stability for them. The second tier – state-level institutions – would receive partial funding directly from the state budget. The third tier, composed of institutions falling under the jurisdiction of voivodes or local governments, would rely entirely on local funding mechanisms.7 Muzeum Sztuki in Łódź was categorized within this lowest tier.8 In effect, what had once been a flagship institution of contemporary art prior to 1989 was now relegated to a level beneath that of the former BWA gallery network, which fell under the state level.

ments, would rely entirely on local funding mechanisms.9 Muzeum Sztuki in Łódź was categorized within this lowest tier.10 In effect, what had once been a flagship institution of contemporary art prior to 1989 was now relegated to a level beneath that of the former BWA gallery network, which fell under the state level.

Ryszard Stanisławski, nearing the end of his tenure, recognized that under this new funding model, the Museum was at risk of institutional collapse. Consequently, shortly after the introduction of the new regulations, he addressed a letter to Minister of Culture Izabella Cywińska, formally requesting that Muzeum Sztuki be placed within the “sphere of direct care and financing”11 of the Ministry of Culture and Art – in other words, to elevate it to the status of a national institution. His appeal was supported by the voivode of Łódź, Waldemar Bohdanowicz, who viewed the change in the Museum’s status as a measure that could stabilize the voivodeship’s strained cultural budget.

Despite initial declarations of willingness to consider the Museum for national status, a number of legal complications soon emerged. A letter dated 27 December 1990 – initiated while Stanisławski was still in office and addressed to Michał Jagiełło, Undersecretary of State at the Ministry – reveals that the legal status of Muzeum Sztuki was unclear. The same ambiguity applied to the Central Bureau of Art Exhibitions and the Foksal Gallery, which operated within its framework.12 As noted by the authors of the memorandum, neither the Museum nor the Exhibition Bureau was owned by the State Treasury; rather, they constituted municipal property – of Łódź in the case of the Museum, and of Warsaw for the Exhibition Bureau. Accordingly, for the Ministry to assume direct responsibility for Muzeum Sztuki, several conditions would have had to be fulfilled: it would need to be “recognized as a museum of exceptional significance […]; designated as an institution engaged in the dissemination of culture of national importance […]; and formally submitted to the Council of Ministers for recognition as an organizational entity of supra-regional or national character […].”13 An alternative, more pragmatic solution involved the Ministry entering into a co-financing agreement with the mayor of Łódź, which would have effectively moved the Museum into the “state” category. Under such an arrangement, the city would remain the Museum’s legal organizer, while the Ministry would contribute to its financial support.14

The Ministry supported the request, citing a legal opinion regarding the voivode’s current authority over museum institutions. Referring to the Act on the Protection of Cultural Property and Museums, the opinion questioned the appropriateness of applying the category of “municipal property” in the case of Muzeum Sztuki, emphasizing instead that the Museum continued to be financed from the state budget, for which the Voivode of Łódź was the authorized administrator.15 As the document states, “the Museum’s activities are undoubtedly within the jurisdiction of the government administration. The financing of such activities by the state budget indicates that the government administration bodies have assumed responsibility for the operation of the Museum of Art in Łódź.”16 Despite assurances from the government side acknowledging the Museum’s exceptional status, the institution ultimately remained under the authority of the voivode of Łódź,17 as decided by the Ministry.

“Necessity Dictates,” or Belt-Tightening

Upon assuming the directorship of Muzeum Sztuki in Łódź on July 1, 1991 – by appointment of the Voivode of Łódź, Waldemar Bohdanowicz – Jaromir Jedliński inherited an institution of outstanding reputation, yet plagued by severe infrastructural deficiencies. Chief among these was the urgent need for the renovation of the building located at the intersection of Gdańska and Więckowskiego Streets. This state of affairs is clearly reflected in the minutes of a meeting held on February 13, 1990, which focused on the Museum’s precarious housing conditions. Ryszard Stanisławski expressed it unequivocally: “the current circumstances preclude any further development of the institution’s activities.”18 Echoing this assessment, Jedliński declared no less categorically that “infrastructural circumstances force the Museum to give up organizing exhibitions that could be events not only on a national, but also on a European scale […].”19 These remarks pertained specifically to the newly inaugurated Księży Młyn20 branch of the Museum, opened in 1990 after a protracted and financially draining renovation effort, which had severely depleted the institution’s resources. It was at the Księży Młyn residence that Stanisławski bid farewell to the Museum’s staff and formally transferred to Jedliński yet another facility to be maintained.

The establishment of another branch of the institution necessitated the creation of new positions; however, in the early 1990s, approximately 90% of the budgets of cultural institutions were already absorbed by staff salaries.21 Yet it was not solely the Księży Młyn branch that generated significant expenses. According to the financial plan for 1991, the organization of fourteen scheduled national and international exhibitions consumed roughly one-third of the funds required at the time for the major renovation of the Museum’s seat at ul. Więckowskiego 36 – and amounted to nearly the same as the institution’s total wage expenditure. As early as August 1991, Jedliński appealed to the municipal authorities for subsidies to support the adaptation and furnishing of planned guest accommodation in the Księży Młyn residence. The rationale was long-term savings: by maintaining its own guest rooms, the Museum could reduce dependence on external hotel services.22 That same year, Jedliński also sought funding for the renovation of the exhibition infrastructure at ul. Więckowskiego 36, where the last significant refurbishment had taken place shortly after Stanisławski assumed directorship in the late 1960s. The requested support was granted indirectly – through an increase in the 1992 budget – with a stipulation that 150 million be allocated to the presentation of the collection from the Musée d’Art Contemporain in Lyon, which was to occupy all available galleries. This would prove to be the final grant Jedliński received for infrastructural purposes.

Visit of a group of German museum professionals to the Muzeum Sztuki, including a tour of the exhibition Musée d’Art Contemporain, Lyon. Collection-Kolekcja, June 1992. From left: Christoph Brockhaus (Director, Wilhelm Lehmbruck Museum, Duisburg), unidentified, unidentified, Ryszard Stanisławski, Jaromir Jedliński. Photo: Archives of the Muzeum Sztuki in Łódź.

In September 1991, the Voivodeship Office informed the Museum of the government’s decision to reduce funding for culture and the arts by 31.3%. Consequently, the institution was instructed to revise its budget accordingly and operate under an austerity regime through the end of the fiscal year.23 Grants designated for renovation and capital investments were likewise subject to proportional reduction. Barely a month later, the cut in cultural funding had deepened to 35.2%.24 Simultaneously, the Department of Social Infrastructure within the Voivodeship Office expressed serious reservations about the financial management of Muzeum Sztuki in Łódź. It was noted that the Museum had already exceeded its 1991 subsidy by September, effectively placing an additional burden on the following year’s budget. The principal charge against Jedliński was his alleged failure to implement “radical measures to adjust the scope of substantive activities to the financial resources at hand.”25 In other words, he was expected to “tighten the belt” more aggressively. Further concerns were raised regarding the administration of the salary fund, which by the end of September had been depleted by nearly 85%.

In response, Jedliński committed to implementing a series of cost-saving measures, including the postponement of Stanislav Kolíbal’s exhibition to the following year, the cancellation of a planned international presentation of works by Katarzyna Kobro, and the abandonment of catalogue publications dedicated to Magdalena Abakanowicz and Daniel Buren. He also explored the possibility of leasing out the Museum’s Photo Studio as an additional source of income. However, the most radical measure by far was the reduction of staff by twenty (!) positions in total, with ten eliminated in September and another ten in November.26 Jedliński emphasized that demanding a budget reduction by a third with merely four months remaining in the fiscal year was a virtually unmanageable expectation. Nevertheless, he assured the authorities that the measures undertaken would begin to yield tangible results as early as the beginning of 1992.27

Owing to the “extremely difficult situation of the state,”28 there loomed the risk of a substantial reduction in the Museum’s subsidy for the following year – though, in the end, this did not materialize. Nevertheless, this prospect did not deter Jedliński from submitting further funding requests to representatives at various levels of government. These included applications for the purchase of a museum vehicle – expected, like the guest rooms, to yield long-term savings – and for the acquisition of works for the collection. Both the vehicle and the artefacts listed in an annex (now missing from the archival documentation) were each estimated to require grants of 450 million zlotys (equivalent to 45,000 zlotys post-denomination29). When such targeted funding requests are juxtaposed with the institution’s financial situation – its debt as of 18 November 1992 amounted to 686,550,200 zlotys (i.e., 68,655 zlotys)30 – Jedliński’s efforts may well be read as “wishful thinking in neoliberal reality.”31 Indeed, calls for fiscal discipline continued to be reiterated by the Museum’s organizers, while inflation further exacerbated operating costs. Jedliński sounded the alarm that, under such unfavorable conditions, the Museum’s substantive activities would face severe curtailment. The budget planned for 1993 reflected this pressure: approximately 80% – 5.142 billion out of a total of 6.7 billion zlotys – was absorbed by payroll expenses, despite a 5% reduction in the wage fund compared to the previous year.32 The director announced that he would continue to apply for additional subsidies. Later that same month, he addressed a request to the State Committee for Scientific Research for funding to develop a system for documenting the Museum’s art collections33 via an internal computer network34 – unsuccessfully. In practice, the gradual computerization of the Museum’s operations was more improvised than systemic. Suffice it to say that the institution’s first computer was primarily operated by long-time staff member Lech Lechowicz, at whose workstation a queue often formed.35

“I Have Significantly Reduced Headcount,” or Collapse

After two years of Jedliński’s tenure, staff morale had plummeted. The earlier round of redundancies had provoked deep anxiety about the institution’s future.36 While archival records suggest that these decisions were intended to provide one-time relief for the Museum’s strained budget, it may also be inferred that they reflected a longer-term managerial strategy. In a questionnaire-based interview with Jaromir Jedliński – published in the 2015 monograph of Muzeum Sztuki in Łódź – the Museum’s director from 1991 to 1996 states plainly:

I assumed directorship in mid-1991. It was a time of transition – in Poland, in Europe, across the world. A liminal moment. Here – a passage from the old regime to the new. I believed that the first thing that needed to change was the internal organization of the Museum’s work. I immediately dismissed the deputy director, the chief registrar, and the chief accountant, and restructured the secretariat as well as the departments responsible for exhibitions and publications. I significantly reduced staff numbers, convinced that a smaller team would prove more agile. The curatorial departments, however, remained largely unchanged; I considered the continuity of knowledge, experience, and institutional memory to be vital.37

Jedliński’s intentions, however, had little discernible impact on staff sentiment; on the contrary, by assuming the role of a modern manager, he risked becoming, in the eyes of the employees, an even more alien figure whose actions appeared, at the very least, incomprehensible. The first documented signs of conflict between the director and the staff – formalized through the only trade union then active within the institution, the Company Committee of the Independent Self-Governing Trade Union “Solidarity” – date back to July 1993. The divergence of views was further exacerbated by a breakdown in communication, itself the result of the broader climate of financial uncertainty plaguing the cultural sector. The Museum’s budget was subject to extremely frequent revisions, each aimed at its incremental reduction; these adjustments were, at times, misinterpreted as – or rather, conflated with – unilateral changes to the institution’s remuneration policies, introduced without prior consultation with union representatives. That said, internal correspondence from the period clearly reveals that, from the employees’ perspective, both the financial condition of the Museum and Jedliński’s method of managing it were perceived as fundamentally anti-worker. It should nevertheless be emphasized that the root cause of this situation lay in the cultural policies of the state – and, by extension, in the conduct of the supervising authority.

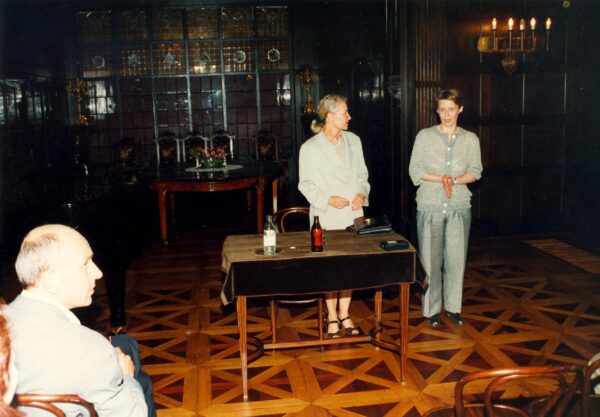

This does not alter the fact that, within the Museum itself, this period came to be referred to simply as “the collapse.”38 What most deeply unsettled employees was the steady exodus of staff – whether to other institutions or to entirely different industries, particularly in the private sector – as well as the pervasive organizational disarray, economic decline, and, not least, the unfolding drama of Łódź’s industrial breakdown, which they experienced firsthand on a daily basis. A recurring motif in the testimonies of employees from the Education Department is the image of children from the Old Polesie neighborhood,39 who would regularly appear at the Museum on Thursdays – the day of free admission – not to participate in educational programs or to view exhibitions, but simply to get warm. In time, these children would be offered pastries, purchased privately by staff. It appears that Jedliński failed to recognize the moment when the role and function of the Museum shifted dramatically – not only in terms of its artistic mission, but in relation to its social responsibilities. Public programming that engaged with socio-economic realities remained minimal. Among the few exceptions were the lecture Społeczeństwo w transformacji. Próba oceny (Society in Transition. An Attempt at Assessment) by Jadwiga Staniszkis (21 May 1993), and a meeting with Anne Butterfield, president of an American consultancy firm, devoted to marketing and public relations in cultural institutions (21 January 1994).

Lecture by Jadwiga Staniszkis, Society in Transition: An Attempt at Evaluation, 21 May 1993. From left: Jaromir Jedliński, Jadwiga Staniszkis, Krystyna Jasińska. Photo: Archives of the Muzeum Sztuki in Łódź.

No educational initiatives addressed the immediate situation in Łódź, despite the fact that the social consequences of the economic transformation were starkly visible throughout the city.

Nor did the Program Department address these pressing social realities – throughout the first half of the 1990s, the Museum’s exhibition program, unlike its limited educational efforts, functioned within a social vacuum.40 Jedliński’s curatorial strategy appears, in many respects, as an effort to continue the vision established by Ryszard Stanisławski. As Jedliński himself later remarked,

The emphasis (perhaps too much? – I wanted the Museum to be talked about) was on exhibitions organized at the Museum and by the Museum beyond its own premises. Between 1991 and 1996, we mounted numerous first institutional exhibitions of major contemporary Polish artists, such as Edward Krasiński, Zbigniew Gostomski, Jarosław Kozłowski, and Krzysztof Wodiczko; we presented exhibitions that introduced younger artists – such as Mirosław Bałka and Mariusz Kruk – to the world of art museums; and year after year, we held exhibitions devoted to key figures of the avant-garde (and simultaneously, to those who had laid the intellectual and artistic foundations of Muzeum Sztuki) on the centenary of their birth – such as Władysław Strzemiński, Henryk Stażewski, and Maria Ewa Łunkiewicz-Rogoyska […].41

32 Charges

With each passing year of Jedliński’s tenure, the Museum’s budget continued to shrink, while its debt steadily increased – as evidenced by mounting demands for overdue payments, refusals to award new subsidies, and rejections of requests to increase existing ones. The relationship between the Museum’s director and its organizing authorities grew increasingly strained, having been effectively reduced to an ongoing renegotiation of budgetary allocations. Marian Łabędzki, Deputy Voivode of Łódź, noted with some exasperation that no other institution under the Voivodeship Office’s supervision submitted financial projections at as high a level as Muzeum Sztuki. Jedliński’s request in May 1995 for a subsidy nearly double that of the previous year42 added fuel to the fire. By this point, the internal situation had also become a matter of grave concern to the Museum’s staff. In official correspondence to the director, the chief accountant repeatedly called for a reassessment of the budget and a revision of existing financial commitments, which made the repayment of outstanding debts effectively impossible.43

Jedliński’s contract was terminated following his refusal to accept the financial plan for 1996, which projected a 20% reduction in funding compared to the previous year. Although the voivode acted within the bounds of legal and permissible procedures for dismissal, the decision provoked a sense of bewilderment in parts of the artistic and academic community. Figures such as Ryszard Kluszczyński, Józef Robakowski, Edward Łazikowski, and Grzegorz Musiał, among others, issued appeals urging the voivode to reconsider. Their arguments emphasized Jedliński’s tireless efforts to make the collection accessible to the public and to organize exhibitions devoted to Strzemiński and Stażewski, accompanied by symposia that attracted speakers and guests from, as one account put it, “literally everywhere.”44 There is little doubt that Jedliński had succeeded in maintaining the Museum’s high level of scholarly and curatorial standards.

Visit by Richard Demarco with an international group of art historians to the exhibitions Krzysztof Wodiczko and Jerzy Kosiński: The Face and the Masks, 1992. Photo: Archives of the Muzeum Sztuki in Łódź.

This response reveals the art community’s prioritization of preserving the institution’s artistic and intellectual stature.45 What went largely unnoticed, however, was that the Museum lacked the resources not only to implement its program but also to sustain its full-time staff or undertake the infrastructural development it so urgently required.

This is well illustrated by the reaction to the letter published by the Board of the Polish Section of AICA in defense of Jedliński. The arguments presented by Anda Rottenberg, Elżbieta Grabska, and Wiesław Borowski centered primarily on “the need to continue Stanisławski’s vision,” which Jedliński was seen to embody and uphold.46 The staff of Muzeum Sztuki in Łódź, however, expressed astonishment at the position taken by the critics’ professional organization – believing that AICA lacked a comprehensive understanding of the internal situation and therefore had no legitimate mandate to intervene in matters concerning the director’s dismissal. In response to AICA’s appeal, the Museum employees – including members of AICA themselves – issued a strongly worded statement outlining serious shortcomings in the institution’s management, as confirmed by surviving documents and correspondence with the organizing authorities.47 Among their accusations were charges of “grave legal and financial misconduct long committed by the deposed director,” which had, they claimed, led to a “4.5 billion złoty deficit of a state institution.”48

Further letters and appeals were issued in Jedliński’s defense. Across all of them, the emphasis consistently fell on the director’s unquestionable intellectual and curatorial merits. However, little to no attention was paid to the institutional cost of his management strategy. As surviving documentation reveals, the implementation of a program widely praised for its artistic value was frequently accompanied by violations of financial discipline. A telling example is the aforementioned 1994 exhibition of works by Henryk Stażewski, for which the Museum had received additional funding from its organizers. An audit conducted by the Finance Department of the Łódź Voivodeship Office found that 10,000 złotys from these funds had been used to cover catering expenses at the Grand Hotel49 – rather than being allocated directly to the production of the exhibition.

This was just one of many findings included in the 1995 report by the Supreme Audit Office. Other identified deficiencies included overdue rent payments; a lack of funds for cleaning staff salaries; unpaid fees to a company responsible for the care of monuments; the failure to implement a system for document circulation in 1991; opaque procedures for renting housing to employees and collaborators, particularly the failure to charge interest; and the misclassification of income from rentals and donations. In total, the list comprised 32 formal allegations or irregularities.

Jedliński’s successors, Nawojka Cieślińska-Lobkowicz and Jacek Ojrzyński, each served as director for only a few months between 1996 and 1997 – a fact that underscores the persistence of the structural crisis at Muzeum Sztuki in Łódź. Their brief tenures also marked the final attempts to preserve the institution’s identity as “Stanisławski’s museum.” A new chapter in the Museum’s history began under the directorship of Mirosław Borusiewicz, who led the institution from 1997 to 2005. His departure coincided with the end of the post-socialist transformation and the beginning of a new phase in Polish modernization, linked to the country’s accession to the European Union.50

This article has sought to outline the institutional history of Muzeum Sztuki in Łódź during the first and most turbulent phase of systemic transformation. Both the issues highlighted here and, above all, the Museum’s activities between 1996 and 2005 warrant further, in-depth scholarly investigation. The year 2005 provides a meaningful caesura – not only because it marks the end of Borusiewicz’s tenure, but also because it was the year the Museum, after many years of effort, finally came under joint management by the Ministry – not only of Culture, but also of National Heritage.

Translated by Karol Waniek

Bibliography

Archives:

State Archive in Łódź

Olga Stanisławska’ss private archive

Archives of Muzeum Sztuki in Łódź

Elaborations:

Banasiak, Jakub. Proteuszowe czasy. Rozpad państwowego systemu sztuki 1982–1993. Warsaw: Akademia Sztuk Pięknych w Warszawie; Muzeum Sztuki Nowoczesnej w Warszawie, 2020.

Drenda, Olga. “Dalekopis i awangarda.” In Proszę mówić dalej. Historia społeczna Muzeum Sztuki w Łodzi, edited by Marta Madejska, Aga Pindera, and Natalia Słaboń. Łódź: Muzeum Sztuki w Łodzi, 2022.

Gierat-Bieroń, Bożena. Ministrowie kultury doby transformacji 1989–2005 (wywiady). Kraków: Universitas, 2009.

Golka, Marian. Transformacja systemowa a kultura w Polsce po 1989 roku. Studia i szkice. Warszawa: Instytut Kultury; Ministerstwo Kultury i Sztuki, 1997.

Jedliński, Jaromir. “Kwestionariusz.” In Kwestionariusz. Jaromir Jedliński. Monografia. Muzeum Sztuki w Łodzi. Tom I, edited by Andrzej Jach, Katarzyna Słoboda, Joanna Sokołowska, and Magdalena Ziółkowska, 767–68. Łódź: Muzeum Sztuki w Łodzi, 2015.

Kostyrko, Tomasz, and Marek Czerwiński, eds. Kultura polska w dekadzie przemian. Warsaw: Instytut Kultury, 1999.

Krzysztofek, Kazimierz. “Ewolucja założeń i programów polityki kulturalnej w Polsce.” In Kultura polska w dekadzie przemian, edited by Tomasz Kostyrko and Marek Czerwiński. Warsaw: Instytut Kultury, 1999.

Madejska, Marta, Aga Pindera, and Natalia Słaboń, eds. Proszę mówić dalej. Historia społeczna Muzeum Sztuki w Łodzi. Łódź: Muzeum Sztuki w Łodzi, 2022.

Musiał, Wiesław. Modernizacja Polski. Polityki rządowe w latach 1918–2004. Toruń: Wydawnictwo Naukowe Uniwersytetu Mikołaja Kopernika, 2013.

Plebańczyk, Krzysztof. “Prawne aspekty działalności kulturalnej w latach 90. – projekty reform ustrojowych.” Zarządzanie w Kulturze 3 (2002): 38.

Świdziński, Wojciech. “Współprowadzenie instytucji przez Ministra i samorządy. ‘Dar niebios’ czy ryzykowna gra?” Zarządzanie w Kulturze 22, no. 1 (2021): 1–14.

Turowski, Andrzej. “Otwarte ku współczesności.” In Tygodnik Kulturalny Verte, Gazeta Wyborcza, 12 January 1996, 2.

- Thanks to the generosity of Olga Stanisławska, I also had access to the private archive of Ryszard Stanisławski, who documented the situation at the Muzeum Sztuki in Łódź at the time by preserving copies of letters, press clippings, and personal correspondence. ↩︎

- One of the first studies on this subject was Marian Golka, Transformacja systemowa a kultura w Polsce po 1989 roku. Studia i szkice (Warsaw: Instytut Kultury; Ministerstwo Kultury i Sztuki, 1997). The most significant work in this field remains Kultura polska w dekadzie przemian, edited by Tomasz Kostyrko and Marek Czerwiński (Warsaw: Instytut Kultury, 1999). See also: Krzysztof Plebańczyk, “Prawne aspekty działalności kulturalnej w latach 90. – projekty reform ustrojowych,” Zarządzanie w Kulturze 3 (2002): 38. The impact of the transformation on the visual arts patronage system is analyzed in detail by Jakub Banasiak, Proteuszowe czasy. Rozpad państwowego systemu sztuki 1982–1993 (Warsaw: Akademia Sztuk Pięknych w Warszawie; Muzeum Sztuki Nowoczesnej w Warszawie, 2020). ↩︎

- Bożena Gierat-Bieroń, Ministrowie kultury doby transformacji 1989–2005 (wywiady) (Kraków: Universitas, 2009). ↩︎

- Kazimierz Krzysztofek, “Ewolucja założeń i programów polityki kulturalnej w Polsce,” in Kultura polska w dekadzie przemian, ed. Tomasz Kostyrko and Marek Czerwiński (Warszawa: Instytut Kultury, 1999), 272, quoted in Banasiak, Proteuszowe czasy, 431. ↩︎

- Based on: Banasiak, Proteuszowe czasy, chap. 14. ↩︎

- Krzysztof Plebańczyk, “Prawne aspekty działalności kulturalnej w latach 90. – projekty reform ustrojowych,” Zarządzanie w Kulturze 3 (2002): 38. ↩︎

- Ibid. ↩︎

- This situation persisted until 2005, when the Ministry of Culture and National Heritage began co-managing the Museum. ↩︎

- Ibid. ↩︎

- This situation persisted until 2005, when the Ministry of Culture and National Heritage began co-managing the Museum. ↩︎

- Letter from Ryszard Stanisławski to Izabella Cywińska, 4 September 1990. Archive of Muzeum Sztuki in Łódź. ↩︎

- Note dated 29 December 1990. Archive of Muzeum Sztuki in Łódź. ↩︎

- Ibid. ↩︎

- Ibid. On the subject of joint management of institutions by organizers at various levels of state administration, see: Wojciech Świdziński, “Współprowadzenie instytucji przez Ministra i samorządy. ‘Dar niebios’ czy ryzykowna gra?” Zarządzanie w Kulturze 22, no. 1 (2021): 1–14. ↩︎

- Legal opinion dated 4 March 1991 regarding the note of 29 December 1990. Archive of Muzeum Sztuki in Łódź. ↩︎

- Ibid. ↩︎

- The Museum was not an isolated case of an institution that, facing the threat of underfunding, sought the status of a national institution. A similar situation occurred, for example, in the case of the Słowacki Theatre in Kraków. In that instance, the theater’s management decided to announce the closure of the institution due to “the state patron systematically failing to pay the subsidy.” See Krzysztof Plebańczyk, “Prawne aspekty działalności kulturalnej w latach 90. – projekty reform ustrojowych,” Zarządzanie w Kulturze 3 (2002): 38. ↩︎

- Minutes from the meeting of 13 February 1990. Archive of Muzeum Sztuki in Łódź. ↩︎

- Ibid. ↩︎

- The Księży Młyn residence is now known as the “Herbst Palace Museum” and is Muzeum Sztuki’s third branch – historically, its second – in which primarily historical art from the museum’s collection is displayed. The building was granted to Muzeum Sztuki in 1977. ↩︎

- Golka, Transformacja systemowa, 31. ↩︎

- Letter from Jaromir Jedliński to Elżbieta Hibner, 6 August 1991. Archive of Muzeum Sztuki in Łódź. ↩︎

- Letter from the Voivodeship Office, 4 September 1991. Archive of Muzeum Sztuki in Łódź. ↩︎

- Letter from Lech W. Leszczyński, 14 October 1991. Archive of Muzeum Sztuki in Łódź. ↩︎

- Ibid. ↩︎

- Response from Jaromir Jedliński, 7 November 1991. Archive of Muzeum Sztuki in Łódź. ↩︎

- Ibid. ↩︎

- Letter from Lech W. Leszczyński, 31 July 1992. Archive of Muzeum Sztuki in Łódź. ↩︎

- Poland redenominated its currency on January 1, 1995, introducing the new złoty (PLN) at an exchange rate of 10,000 old złoty (PLZ) to 1 new złoty. The reform was implemented to counteract the effects of hyperinflation from the late 1980s and early 1990s and to simplify financial operations. ↩︎

- Statement of debt, 1992. Institutional Archive of the Museum of Art in Łódź. ↩︎

- Golka, Transformacja systemowa, 15. ↩︎

- Letter from Jaromir Jedliński, 11 December 1992. Archive of Muzeum Sztuki in Łódź. ↩︎

- During Jaromir Jedliński’s tenure, the collection of Muzeum Sztuki grew by approximately 10% (around 1,400 objects, including donations and long-term deposits). See Jaromir Jedliński, “Kwestionariusz,” in Kwestionariusz. Jaromir Jedliński. Monografia. Muzeum Sztuki w Łodzi. Tom I, edited by Andrzej Jach, Katarzyna Słoboda, Joanna Sokołowska, and Magdalena Ziółkowska (Łódź: Muzeum Sztuki w Łodzi, 2015), 767. ↩︎

- Letter from Jaromir Jedliński to the State Committee for Scientific Research, 30 December 1992. Archive of Muzeum Sztuki in Łódź. ↩︎

- Olga Drenda, “Dalekopis i awangarda,” in Proszę mówić dalej. Historia społeczna Muzeum Sztuki w Łodzi, edited by Marta Madejska, Aga Pindera, and Natalia Słaboń (Łódź: Muzeum Sztuki w Łodzi, 2022), 104. ↩︎

- This information is based on correspondence between the trade unions, the voivode, and the director (Archive of Muzeum Sztuki in Łódź). As the material is marked confidential, I have chosen to present only generalized observations and conclusions, without disclosing more detailed information. ↩︎

- Jedliński, “Kwestionariusz,” 769. ↩︎

- This statement was made during one of the interviews with a former employee of Muzeum Sztuki in Łódź, conducted as part of the project provisionally titled Opowiedzieć Muzeum (2018–2022). The project is partially summarized in the publication Proszę mówić dalej. Historia społeczna Muzeum Sztuki w Łodzi, edited by Marta Madejska, Aga Pindera, and Natalia Słaboń (Łódź: Muzeum Sztuki w Łodzi, 2022). ↩︎

- The district where the original seat of Muzeum Sztuki in Łódź – now known as ms1– is located. ↩︎

- In its pioneering projects such as Podwórka Stażewskiego (Stażewski’s Courtyards), the Education Department extended its activities beyond the institution’s walls – the dissemination of knowledge about the museum’s avant-garde idiom was meant to take place in the social realm. ↩︎

- Jedliński, “Kwestionariusz,” 768. ↩︎

- Letter from Marian Łąbędzki to Jaromir Jedliński, 22 May 1995. Archive of Muzeum Sztuki in Łódź. ↩︎

- Letter from Elżbieta Głowacka to Jaromir Jedliński, 23 January 1996. Archive of Muzeum Sztuki in Łódź. ↩︎

- Open letter to the voivode of Łódź, Gazeta Wyborcza, 8 February 1996. ↩︎

- In a text published in Gazeta Wyborcza, Andrzej Turowski defended Jedliński’s vision, which he saw as a natural continuation of Stanisławski’s program and in keeping with the ethos of the museum of the avant-garde. Turowski also opposed the change in directorship in an open letter, warning that such a decision could destabilize or even destroy the institution’s reputation and international significance. He was joined by artists such as Magdalena Abakanowicz and art critics like Wiesław Borowski of Galeria Foksal. ↩︎

- Andrzej Turowski, “Otwarte ku współczesności,” in Tygodnik Kulturalny Verte, Gazeta Wyborcza, 12 January 1996, 2. ↩︎

- Response from Muzeum Sztuki in Łódź staff to the AICA letter, private archive of Ryszard Stanisławski, courtesy of Olga Stanisławska. ↩︎

- Ibid. ↩︎

- External audit of the institution, conducted by the Financial Department of the Voivodeship Office in Łódź. State Archive, file ref. 39/2448/0/-/415. ↩︎

- More on this subject, see: Wiesław Musiał, Modernizacja Polski. Polityki rządowe w latach 1918–2004 (Toruń: Wydawnictwo Naukowe Uniwersytetu Mikołaja Kopernika, 2013). ↩︎

Natalia Słaboń

Head of the Museological Center at Muzeum Sztuki in Łódź since 2024. She is currently pursuing a PhD at the Doctoral School of Humanities at the University of Łódź, focusing on Ryszard Stanisławski. Co-editor of several publications, including Proszę mówić dalej. Historia społeczna Muzeum Sztuki w Łodzi (with Marta Madejska and Aga Pindera), Over There: Works by Alice Halicka from 1913–1947 in Foreign Collections (with Wojciech Szymański), The 1982 Cultural Exchange Between Łódź and Los Angeles (with Aga Pindera), and O naukowości muzeów (with Aga Pindera and Anna Saciuk-Gąsowska). She lectures at the Institute of Contemporary Culture at the University of Łódź.