Title

From Managerial Capitalism to Culture War Debates around the Restructuring of the System of Visual Arts in Post-Socialist Hungary

https://doi.org/10.48285/ASPWAW.29564158.MCE.2024.10.8

Art Fund of the Hungarian People's Republic, Budapest Kunsthalle, post-socialist Hungary, hungarian field of art, Late Socialist Hungary

https://miejsce.asp.waw.pl/en/from-managerial-capitalism-to-culture-war/

Abstract

In late-socialist Hungary, the system for the production and distribution of visual arts underwent significant changes. While marketization increasingly took hold, art policy allowed more space for artists who followed Western trends. After the post-socialist transition of 1989, these processes accelerated, and the protagonists of the former avant-garde – holders of the most important symbolic capital – became the new elite of the artistic field. However, this process also led to intense conflicts and sharp institutional debates. These conflicts did not stop at the edges of the field of artistic production; rather, they became the subject of political battles between leading market-liberal and national-conservative protectionist factions. In this study, I will present the structure of the economic and administrative system of fine arts under state socialism, examine the history of the successor organizations to the Magyar Népköztársaság Művészeti Alapja [Art Fund of the Hungarian People’s Republic], and describe the debates between the Magyar Képzőművészek és Iparművészek Szövetsége [Union / Association of Fine and Applied Artists] and the Budapest Kunsthalle in post-socialist Hungary.

Keywords

Art Fund of the Hungarian People's Republic, Budapest Kunsthalle, post-socialist Hungary, hungarian field of art, Late Socialist Hungary

DOI

Introduction

In the early 1980s, the institutional system of visual arts in Hungary underwent significant changes. As the marketization of the system accelerated, the art policy of the late Kádár regime increasingly accommodated artists who followed international contemporary trends and had previously been marginalized. At the same time, the art system increasingly began to function as a field of cultural production based on symbolic capital and abstract hierarchies.1 After 1989, the most significant symbolic capital – besides demonstrating affiliation with Western artistic trends – became a strong oppositional stance during the pre-1989 era: marked by distance from the socialist institutional system and, even more importantly, by confrontations with state authorities, including banned or censored exhibitions. As a result, art historians, curators, and artists associated with avant-garde and alternative art from the previous era became the most important gatekeepers of the post-socialist artistic field. These artists and theorists, leveraging their symbolic capital, achieved a significant shift in cultural hegemony, allowing art from the formerly restricted production field2 to occupy a symbolically dominant position in major institutions.

The new artistic field was characterized by two types of conflicts. The primary conflict revolved around the control of the field itself – its institutions and the representation of art in general. This debate focused primarily on the exhibition policy of the Kunsthalle, the most important exhibition space for living artists, particularly on the Salon-style exhibitions.

The conflict began in the 1980s, when socialist cultural policy started to favor artists with connections to the West. However, it intensified after 1989, as much of the artistic community faced an escalating existential crisis. From the second half of the 1990s onwards, these debates gradually merged with conservative and liberal political discourses, which increasingly obscured the social and economic stakes of the conflict. The secondary conflicts took place within the restricted field of artistic production. On one hand, these were generational tensions, exacerbated by the institutional over-favoring of the avant-garde generation. On the other hand, they reflected deeper differences in art-related approaches and art theories, as the gatekeepers of the avant-garde were unable to identify with the new contemporary critical theories and trends.

In my PhD dissertation, I analyzed the transformation of the Hungarian art institutional system during the political-economic regime change, along with the main conflicts and debates in the field of visual art in the 1990s.3 I examined this process not only from the perspective of institutions representing avant-garde and contemporary art but also by researching the history of artistic organizations that comprised the majority of the artist community. In this study, I present the transformation of the art institutional system in Hungary during the regime change, focusing on the primary line of conflict in the post-1989 artistic field, i.e., the tension between fine and contemporary art traditions and models.4 In the first part of the study, I describe the operation of the visual arts institutional system under existing socialism and the process of stealth marketization in the 1980s.5 In the second part, I outline the history of the largest artists’ organizations from the previous era which survived the regime change and the economic difficulties faced by the artists they represented. Finally, I describe the conflicts between the Kunsthalle, which represented the new elite of the field alongside with avant-garde and contemporary art, and the Association of Hungarian Fine and Applied Artists, which stood for the declining middle class within the artist community. In doing so, I aim to demonstrate that the conflicts within the field were not merely aesthetic disagreements, but must be understood in light of the economic and political contexts at play. I conclude by pointing out that the story of the regime change was one of winners and losers, and that a more nuanced art historical analysis of the 1990s cannot be limited to canonized art. Instead, it must also consider the internal struggles within the artistic field, along with the goals, interests, and opportunities of artists and cultural producers occupying different positions within it.

The Production and Distribution System of Visual Art in Late Socialist Hungary

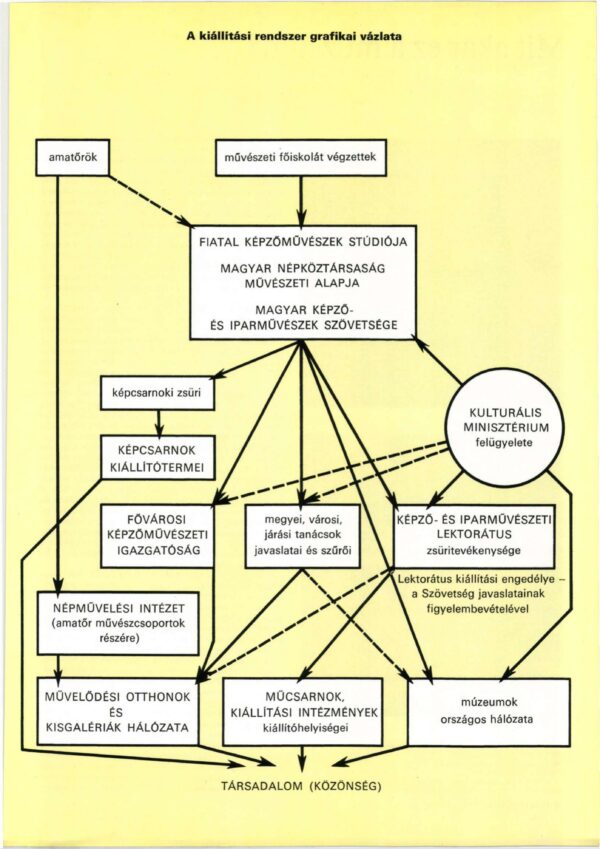

The October 1979 issue of the journal Művészet (Art) was a thematic issue that presented the operational mechanisms of the exhibition system in the visual arts.6

The diagram primarily represents the career opportunities available to artists, while also providing a detailed depiction of the functioning of the institutional system of the visual art at the time. As the diagram shows, state socialist cultural policy divided the artistic community into two groups: professionals and amateurs. Artists under the age of thirty-five could initially become members of the Fiatal Képzőművészek Stúdiója (Young Artists’ Studio). Graduation from the academies of fine or applied arts meant automatic membership in the Art Fund of the Hungarian People’s Republic. From there, artists could apply for admission to the Association of Fine and Applied Artists, which represented the official elite of the artistic community. By comparison, amateur artists could join the Népművelési Intézet (Institute of Civic Cultivation), which allowed them to exhibit in cultural centers and in the so-called “small galleries.”7 The dashed line between amateurs and professionals indicates that the system, in some cases, allowed artists without a degree to apply for membership in the Studio and in the Fund, thus enabling some to become part of the professional art community. Therefore, only professional artists could exhibit in the most esteemed exhibition spaces. Among these, the largest and most prestigious was the Műcsarnok (Budapest Kunsthalle), which, along with several other galleries in Budapest, was part of the Kiállítási Intézmények (Exhibition Institutions).8 On the right side of the diagram, two other crucial institutions are visible: the Képzőművészeti és Iparművészeti Lektorátus (Lectorate of Fine and Applied Arts), which was mainly responsible for the authorization and censorship of exhibitions and public artworks, and the Ministry of Culture. The latter, depicted as the only circular institution in the diagram – as the straight and dashed lines emanating from it indicate – actually oversaw all the other institutions.

By the end of the 1970s, the official art institutional system had integrated a large portion of the artistic community. By this time, artists working in abstract and surrealist styles, once regarded with hostility, had also been members of the Association for over a decade. While conceptual, environmental and performative art still could not be displayed within the professional exhibition system, this began to change by the end of the 1970s. In 1979, preparations were already underway for the Tendenciák (Tendencies), exhibition series, organized by the Association. This series, whih featured art of the 1970s – mainly modern, avant-garde or neo-avantgarde9 – also included a separate show dedicated to conceptual art.10

Financial support for the production and distribution of fine art, as well as for securing artists’ income, was provided mainly by the Fund. In addition to public commissions and occasional state purchases, visual artists’ main source of income was the Képcsarnok Vállalat (Art Retail Company), which accepted artworks on a monthly basis. The state purchases and the Art Retail Company were owned and operated by the Fund, as were three other companies: Iparművészeti Vállalat (Applied Arts Company), Képzőművészeti Kivitelező Vállalat (Fine Arts Production Company) and the Képzőművészeti Kiadó Vállalat (Fine Arts Publishing Company). The Fund also held a state monopoly granting it the exclusive right to produce and distribute postcards in the country, which accounted for more than a third of the Fund’s total income.11 These revenues were used to cover pensions, allowances, advances, insurance of the artists, as well as the costs of the Exhibition Institutions, the Lectorate, and the Association. They also covered the costs of Hungary’s participation in the Venice Biennale and scholarships for younger artists. The Fund had substantial assets, financial reserves, and owned a number of properties. In addition to galleries belonging to the Art Retail Company and to other enterprises, it owned a number of other high-value exhibition spaces, as well as storage facilities, studios, studio apartments, and artists’ houses. Furthermore, until the 1980s, the law on the two-thousandths contribution to art funding was in force. This meant that two-thousandths – or up to half a percent – of the value of public construction projects had to be spent on artworks. However, these amounts were not managed by the Fund but by the Lectorate. Like other systems that existed under state socialism, this scheme was a combination of overproduction and redistribution, and while involving varying degrees of political censorship, it also provided social security for artists.

By the end of the 1970s, the problem of overproduction provoked numerous critiques. These were still Marxist-based critiques, which blamed the system for its non-communist functioning. At a 1979 conference organized by the Association, Gábor Attalai12 stressed that real socialist industrial design and industrial art did not function according to social needs but rather according to the principle of production and consumption characteristic of capitalist societies, resulting in large-scale accumulation and surplus.13 As a solution, Attalai proposed strengthening the crafts and small-scale production apparatuses. László Menyhárt, one of the editors of the journal Művészet, in his article entitled “Who Supports Whom, How and What at Last?” stated that the system preserved and operated a capitalist bourgeois artistic model and had become extremely bureaucratic.14 As a solution, he proposed the authorization of free artists’ cooperatives that had been abolished after the 1956 revolution. In his article “Painting, Art Trade, Patronage”, the publicist and lawyer István Kerékgyártó sharply criticized the operation of the Art Retail Company and state purchases.15 In addition to raising the problem of quality, he also drew attention to the huge stock of unsellable artworks and to what he called the “hidden patronage” problem. By the latter, he meant that many artists were, in fact, working not for the public but for the warehouses, with the management of the Art Retail Company enabling this practice. Finally, Kerékgyártó encouraged purchases from previously banned or marginalized avant-garde artists at both the Art Retail Company and the public sales.

As a result of the global economic crisis of the late 1970s, Hungary fell into a deepening economic downturn and was forced to borrow large amounts of foreign currency. The country’s increasing dependence on the capitalist economy triggered processes of market liberalization, which led to growing decentralization and marketization of the art institutional system. Beginning in the early 1980s, the Art Retail Company underwent a revision: it no longer purchased all works accepted by the juries, but only those deemed sellable. In 1982, the Fund created its fifth company, the General Art Company, which offered artworks, design objects, and home furnishings mainly to foreign customers. In 1985, the Qualitas Gallery opened in Budapest, offering works of art at much higher prices than those available in the Art Retail Company – prohibitively high compared to average salaries.16

At the same time, political authorities and the Party gradually withdrew from direct control over cultural life and the arts.17 As a result, in the second half of the decade, the artistic system increasingly operated as a relatively autonomous artistic field. The main symbol of this shift was the Exhibition Institutions, which, as early as 1984, gained the right to organize their own exhibitions without the permission of the Lectorate. The institution started to provide more and more space for artists representing current Western artistic trends, while the Fund and major museums started to buy works from previously marginalized artists. The gradual withdrawal of cultural policy from the control of art and the relative expansion of Western-connected art sparked heated debates even before 1989, but they intensified when the restructuring of the institutional system escalated to another level.18

Despite the reforms, the economic crisis deepened. In 1983, the Fund –until then an official social organization – was given the status of a ”budgetary body”. In practice, this meant, paradoxically, that the Fund lost its relative independence in the period of so-called stealth marketization. Its revenues were limited to the sums approved by the Ministry of Culture and the Ministry of Finance. As György Horváth puts it in his book about the history of the Fund, after numerous investigations, deductions, and reallocations, the two ministries “bled” the Fund and its significant reserves were totally exhausted.19 In addition, in 1987, the spontaneous privatization process began, during which a significant part of state assets was sold at a low price to party-state elites or foreign investors. This process also affected the system of production and distribution of visual art, as many of the Fund’s estates and movable properties were privatized after 1987. Finally, by the end of the decade, the Fund went bankrupt. In 1988, a year before the regime change, it was only able to pay social benefits and pension supplements to its members by taking state loans.

The Successor Organizations of the Art Fund

From 1988 to the end of 1989, negotiations took place between representatives of the Fund and the Ministry of Culture in an effort to save the Fund and its remaining assets. Against the will of the artists, the ministry reorganized the assets into a government foundation, which remained state property. After a lengthy legal procedure, the Art Fund was officially dissolved in 1992.20 Two institutions were established to replace it: the Magyar Alkotóművészek Országos Egyesülete – MAOE (National Association of Hungarian Artists, hereinafter: MAOE) for the former members of the Fund, and the Magyar Alkotóművészeti Alapítvány (Hungarian Creative Arts Foundation, hereinafter: Foundation) to manage the assets and support the MAOE.21 In 1992 the Fund had 6,000 members, who, after the restructuring, automatically become members of MAOE.22 However, there is currently no data available on how many of them remained active members. MAOE represented a very broad cross-section of the artistic community, but primarily advocated for those artists whose livelihoods had previously depended on Art Retail Company submissions or on the Fund’s companies, or who had created in studios or lived in studio apartments specifically allocated by the Fund. Although some of the assets disappeared during the period of spontaneous privatization, the Foundation still inherited part of the Fund’s assets. These consisted primarily of real estate and financial assets, i.e. shares and securities. The state’s intention was for the Foundation to use these assets to pay the pension supplements and other compulsory benefits for MAOE members. However, most of the properties – such as the artist houses – did not generate revenue but required considerable maintenance expenditures, and many of the properties, such as the Art Retail Company, were operating at a loss. In sum, the combination of the Foundation and MAOE resembled many of the formerly state-owned enterprises: half-closed, semi-privatized, with a large number of underpaid or dismissed workers.

In its early years, the Foundation suffered a significant overall loss of assets. This was due to the economic crisis, the deficit-ridden nature of the inherited assets, and various other external factors.23 By 1995, the Foundation was involved in nearly ninety cases in different courts. These included lawsuits inherited from the Art Fund, cases related to artists’ and workers’ advances, housing loans, real estate disputes, and other small- and large-scale asset-related legal proceedings, including instances of economic fraud. The most notorious of these were the asset cases involving Tamás Schmidt and György Zemplényi, as well as the cases connected to the activities of Tamás Kóka.24 While the Zemplényi case was a proven criminal offense, the Kóka case was an excellent example of the managerial capitalism of the 1990s described by Iványi Szelényi: “Technocracy enjoys post-communism like a fish enjoys water – this society is theirs: it is manager capitalism. Although the politocracy played a key role in determining the direction and dynamics of socio-economic change, it still feels uncertain, even uncomfortable, in its new position.”25

The Schmidt and Zemplényi case received extensive coverage in daily newspapers, tabloids, sports press, and on television. György Zemplényi, the former president of one of the Fund’s subsidiaries, was a professional fraudster who had emigrated to the West in the early 1980s, but came back to Hungary at the end of the decade to take advantage of the opportunities offered by spontaneous privatization. At the beginning of the 1990s, he borrowed hundreds of millions of forints from various private and legal entities, including the Fund. Zemplényi later became president of the Hungarian Swimming Federation, and in 1992, in the middle of the Barcelona Olympic Games, he defected with the borrowed and stolen money. Tamás Schmidt, the former economic director of the Fund, had granted Zemplényi a large loan in 1992. In 1998, Zemplényi was arrested in Sweden, and later both he and Schmidt were convicted of fraud and embezzlement in Budapest.26

In 1993, Tamás Kóka, as head of an asset management company, managed to convince the Foundation’s board that an efficient financial institution could be built from the inherited real estate assets. After taking over asset management, Kóka and his team started liquidating what they considered unviable subsidiaries, which resulted in significant layoffs. However, it soon became clear that Kóka and his associates had drawn enormous salaries, allowances, and substantial loans from the Foundation. Under pressure from MAOE, the board suspended Kóka’s employment. Nevertheless, upon leaving the Foundation, he received a great amount of severance pay.27 Dénes Gábor, Deputy State Secretary for Economic Affair and government-delegated board member, did not support the plan. Later, he commented: “The asset manager presented his ideas excellently with his pleasant and charming manner. I felt like I was hearing nothing. He quoted buzzwords from academic literature, illustrated with excellent projections and flashy diagrams. His enthusiasm and ambition also made him seem sympathetic.”28

In the second half of the 1990s, there were ongoing conflicts between the Foundation and MAOE. The new board of the Foundation, appointed by the government, did not include any artists and saw the solution in selling off some of the Foundation’s property. In contrast, MAOE wanted the state to relinquish control of the Foundation’s assets and transfer them to the artist members. In addition, a sharp conflict arose over the wages of the Foundation’s staff.29 While in the early 1990s more than 50% of MAOE members earned below the official minimum subsistence level, the leadership’s salaries were notably high.30 In this debate, Gábor Székely, the economist and president of the Foundation, provided another striking example of Szelényi’s theory of managerial capitalism when stating: “Even if we can’t pay the artists anything, we still have to pay the staff of the Foundation.”31 In the following years, MAOE continued its efforts to end state control over the assets, but succeeded only in securing government responsibility for financing pension supplements. Following the change of government in 1998, the conflict between MAOE and the Foundation largely subsided, partly because the new conservative government favored greater financial support for MAOE. However, it still did not support the transfer of the Foundation’s assets to MAOE.32

The Association of Hungarian Fine and Applied Artists

The General Assembly of the Association of Hungarian Fine and Applied Artists,33 held in September 1989, adopted a new constitution. As a result, the Metropolitan Court declared the Association a social organization.34 Thus, the Association survived the regime change, although it had lost its financial basis, namely the Fund. Although social organizational status came with some state support, it was insufficient even to cover basic operations. But financial difficulties were only one of the challenges facing the Association. Another was that of self-legitimacy. The organization was founded in 1945 to “create and propagate socialist realist art”35 and represented the official elite of the state socialist artistic community. While the reference to socialist realist art was, of course, removed from the organization’s statutes, this did not solve the deeper issue: by then, the artistic elite had changed. In 1989, the Association had 1,422 members. Some were affiliated with the avant-garde or the political opposition, but they were clearly in the minority. Most were not particularly interested in the organization’s affairs.36 The overwhelming majority were artists who lacked symbolic capital, were disconnected from international contemporary art trends, did not belong to avant-garde or oppositionist circles, and whose livelihood largely depended on an artistic system that was now on the brink of collapse.

In its early years – much like MAOE – the Association of Fine and Applied Artists represented a relatively broad spectrum of the artistic community in terms of party preferences and political ideologies, striving to remain above political battles and maintain a centrist position. In 1990, the Association elected Lajos Németh, an art historian with a considerable standing in both official and underground circles, as its president. Although Németh accepted the nomination, in 1991 he spoke with striking candor about the Association’s legitimacy problems. According to him, although the Association increasingly came into conflict with the official authorities after 1956, and although in the 1960s it began to include avant-garde artists among its members, it was unable to establish any meaningful connection with underground groups. This left the Association stranded in a “no man’s land” between serving official politics and representing “real art”. In the meantime, the balance of power had shifted:

Those who were banned, or at least fell into the “tolerated” category in the infamous “three T’s” system of domestic cultural policy37 became favorites in the West. As a result, the value system of domestic artistic life became more and more confused. The Association was not prepared to take a stand on this issue, let alone because the majority of its members did not even understand the new endeavors, or opposed them.38

Németh argued that the organization had to face the fact that it was increasingly unable to legitimize itself and had ceased to be the “unifier” of the Hungarian visual and applied arts community. Because of this, he maintained, the only viable solution was to transform the Association into a federation of member organizations.

The majority of the Association’s members did not share Németh’s views or support his proposals. After his unexpected death, the 1992 General Assembly elected Pál Gerzson as president of the organization. Gerzson was a typical representative of the majority of the Association members – artists who had lost influential positions after 1989. He had worked as a painting teacher at the Academy of Fine Arts in Budapest from the 1970s and served as head of the painting department from 1987 to 1990, a position he was forced to leave as a result of the 1990 “student revolution.”39 His name had also appeared in Tamás Kerékgyártó’s 1979 article criticizing the functioning of the Art Retail Company. Gerzson did not support Németh’s vision and continued to define the Association as the single elite organization representing leading Hungarian artists.

Between 1992 and 1995, the fault line between supporters and opponents of Németh’s vision deepened significantly. Within the Association, critics who had previously supported avant-garde tendencies had already formed a separate group, the Kállay Ernő Circle, in 1989. However, after 1992, numerous smaller associations also emerged. In 1995, the leaders of thirteen such organizations submitted a statement of intent and a proposal to the Association’s leading body, advocating for its restructuring. When this proposal was rejected by the General Assembly, the Magyar Képzőművészeti és Iparművészeti Társaságok Szövetsége (Federation of Hungarian Fine and Applied Arts Societies) – a conglomeration of seventeen smaller Societies – began operating independently.40 By the end of the decade, the two federations had become essentially hostile towards one another.41

By 1995, the Association and the majority of its artists had reached a nadir – both economically and in terms of self-legitimization. Due to austerity measures and the economic crisis, ministry subsidies were reduced and delayed, leaving the organization unable to pay even the rent for its central office and its phone bills. As a result, it essentially ceased operations in the second half of the year. It was also after 1995 that references to the dire financial situation of artists began to appear more prominently in the Association’s rhetoric. Although many members had likely faced significant financial difficulties as early as the regime change, these issues were, at most, discussed during general assemblies and rarely communicated in the press or the Associations’ journal – Hírlevél (Newsletter). However, after 1995, such references became increasingly frequent. In the first issue of the Newsletter published in 1996, Péter Lelkes, the vice president of the Association, wrote: “The burden of everyday survival weighs heavily on all of us, representing a dramatic struggle for each of us individually. Tensions arise even among us when some face less severe financial difficulties while others experience extreme hardships.”42 The fact that the Federation largely represented the losers of the regime change was most clearly articulated by József Péri and László Sós in their text published in the second issue of the Newsletter in 1998: “What did the regime change bring? Instead of creative work, it imposed idleness; handouts thrown as alms, income replacement subsidies, social allowances, and the vegetating of our creative years.”43

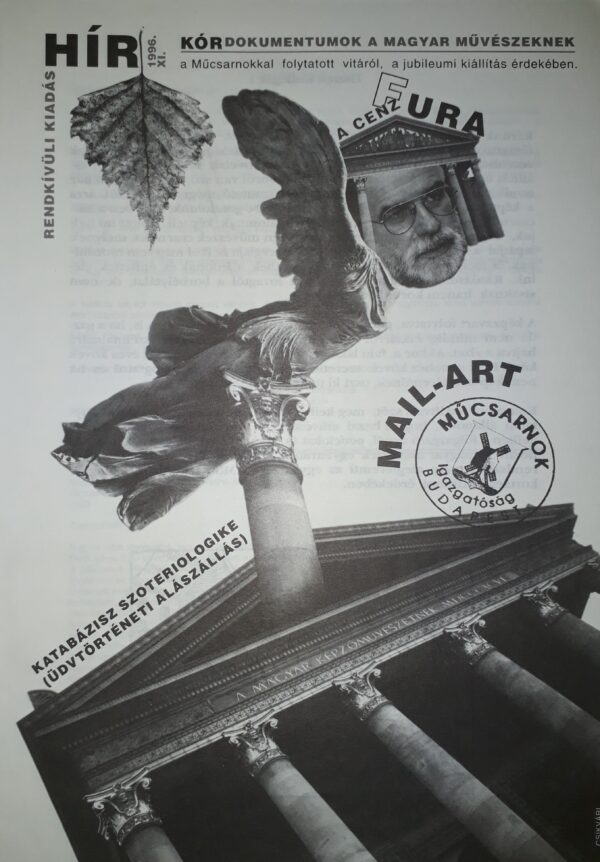

The cover of Hírlevél (Newsletter) 1996/XI features an illustration mocking László Beke, portraying him as a censor of the Kunsthalle. Photo by the author

Following the split in 1995, the Association was regarded even less as the elite organization of Hungarian fine and applied artists than it had been at the time of the publication of Lajos Németh’s proposal. By then, the new reputational elite and the gatekeepers of the artistic field – former avant-garde artists and art historians who had shown any level of engagement with the Association after 1989 – had completely distanced themselves from the organization. Some joined one of the Associations of the new Federation of Hungarian Fine and Applied Arts Societies, but most chose individual paths and hoped for institutional rehabilitation and the spread of a Western-style commercial gallery system. In contrast, Gerzson and other members of the Assocaition promoted the narrative that it was the rightful successor to the Országos Magyar Képzőművészeti Társulat (National Hungarian Artists’ Association), founded in 1861, making it Hungary’s oldest visual arts organization. According to them, the original Társulat had been closed by the communist regime in 1948 and replaced by the Association of Fine and Applied Artists.44 However, this claim does not hold up historically. While it is true that the communist authorities abolished several artists’ organizations in 1948, the National Hungarian Artists’ Association had, in fact, been dissolved earlier.45 Nevertheless, after 1995, this origin story became so widespread in the Association’s rhetoric that its ties to the socialist era were entirely overshadowed. This narrative also served another important purpose: in the state socialist period, the Association had the opportunity to organize salon-style exhibitions at the highly prestigious Budapest Kunsthalle. However, after 1990, both the Association and the artists it represented were excluded from the venue. Since the Kunsthalle had originally been founded by the National Hungarian Artists’ Association in the 19th century, the Association could now, at least theoretically, lay claim to the right to once again hold exhibitions in the building.

The Conflicts Between the Association and the Kunsthalle

The debates between the Association and the Kunsthalle largely mirrored the broader conflicts between contemporary and fine art traditions and models that, according to Octavian Esanu, characterized much of the post-socialist region during the 1990s.46 On one hand, this represented an aesthetic confrontation. Existing socialism had preserved a conservative artistic model, which focused on talent and craftsmanship, while contemporary art emphasized invention, as well as avant-garde and conceptual traditions. On the other hand, it reflected an institutional difference. Although the visual arts system before 1989 operated within a non-democratic political structure, the artists’ organizations were, in theory, set up as autonomous and democratic. Artists had the right to vote, to elect their leaders, to participate in juries, and the system of art distribution in general was also largely managed by the artist communities themselves. Although it was called democratic, the new contemporary curator-manager model was based on abstract hierarchies, reputations, symbolic capitals, and generally aligned with the cultural policies of late capitalism.

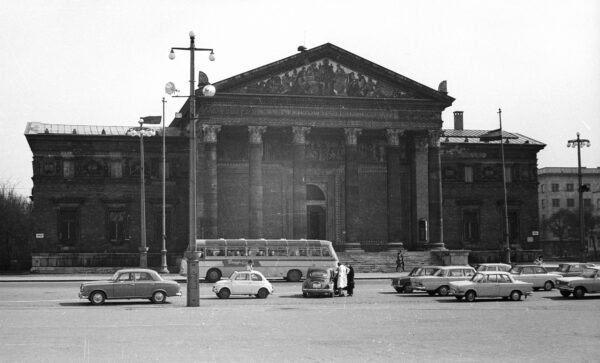

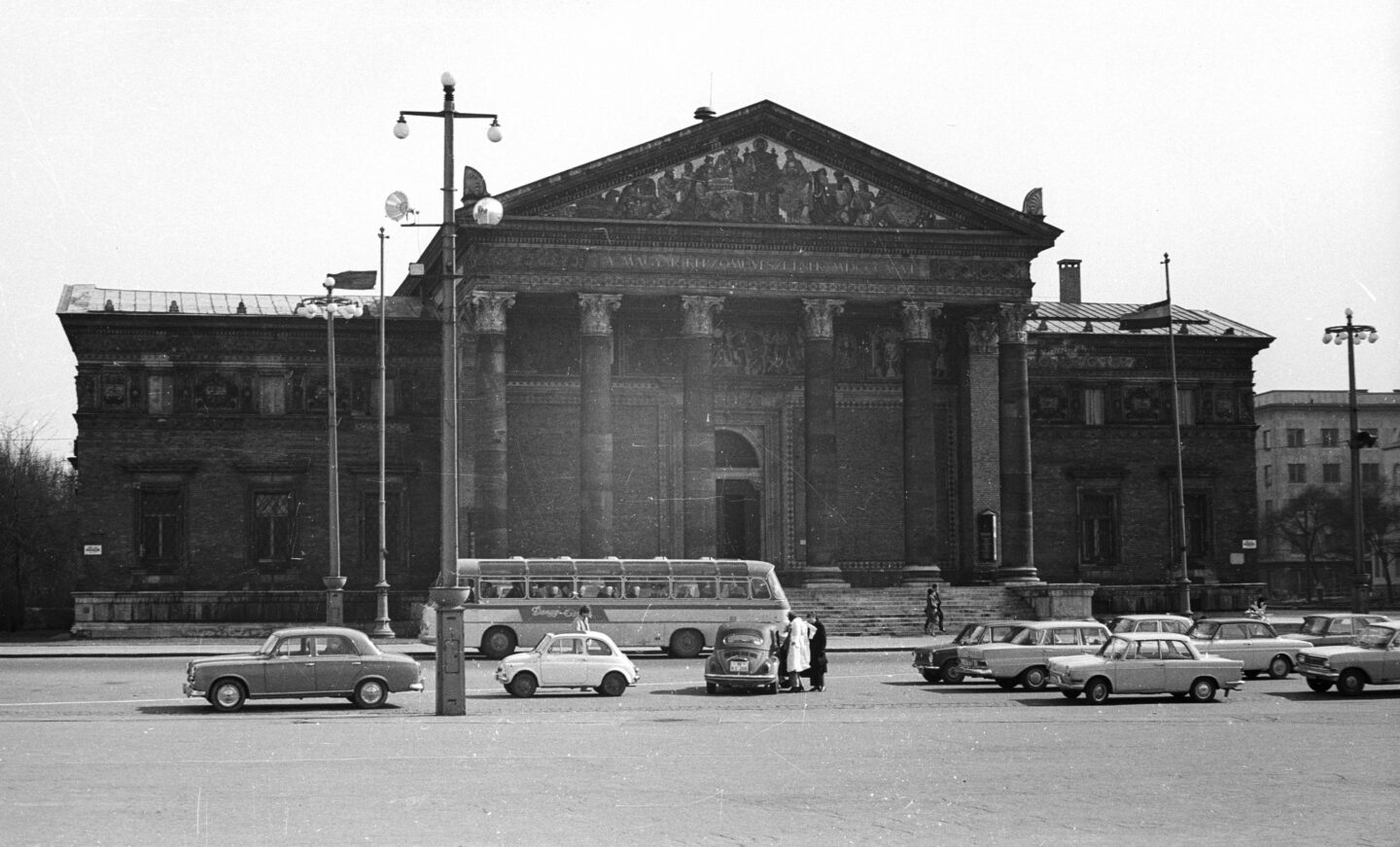

The reburial of the heroes of 1956 in front of the Kunsthalle at the Budapest Heroes Square (June 16, 1989) was one of ten most important mass events of the transition in Hungary. Photo: Fortepan/tm

In this process, Esanu attached great importance to the spread of the Soros Centers for Contemporary Arts (SCCA), which, after 1989, found themselves in opposition to the local artist unions/associations.47 The SCCA and the Kunsthalle were closely connected, as the former had already begun operating in the Kunsthalle in 1985. The SCCA (then called the Documentation Center) primarily focused on gathering modern and postmodern artists who could be integrated into the Western art world.48 At the same time, the official salon-type exhibitions traditionally organized by the Association were gradually replaced by curator-led shows. After the regime change, the institution began organizing exhibitions for previously marginalized and/or avant-garde artists – primarily from 1995, when the leadership of the institution was taken over by László Beke, one of the most prominent art historians and curators of the avant-garde in the previous era, and who, after 1989, become one of the most important gatekeepers of the artistic field. In addition to the so called “rehabilitation exhibitions,” the new director gave significant space to exhibitions representing art from the region, as well as to intermedia and net art exhibitions, frequently realized with the support of the SCCA.

The Association, which represented the fine art tradition and model, had already criticized the operation of the Kunsthalle before 1989, and after the regime change, repeatedly requested the organization of salon-type exhibitions. In 1991, the Association was granted the opportunity to organize a salon exhibition in the building, but the show received overwhelmingly negative criticism.49 After 1991, it seemed that salon-type exhibitions were off the agenda and that contemporary art could finally gain a hegemonic position in the main institutions. However, from the middle of the decade, the debates around the Kunsthalle and the salon took on a political dimension. That year, the country celebrated the 1100th anniversary of the Hungarian conquest of the Carpathian Basin. One hundred years earlier, in 1896, this celebration had been a grand festivity for Hungary. Many of Budapest’s landmark buildings were constructed for that occasion, among others, the current building of the Kunsthalle, which also opened at that time. Although celebrations were held across the country, the commemorative year became politicized. Right-wing intellectuals and politicians – including members of FIDESZ, which was in opposition at the time50 – fiercely criticized the ruling liberal-socialist coalition, arguing that it failed to honor the year appropriately.51

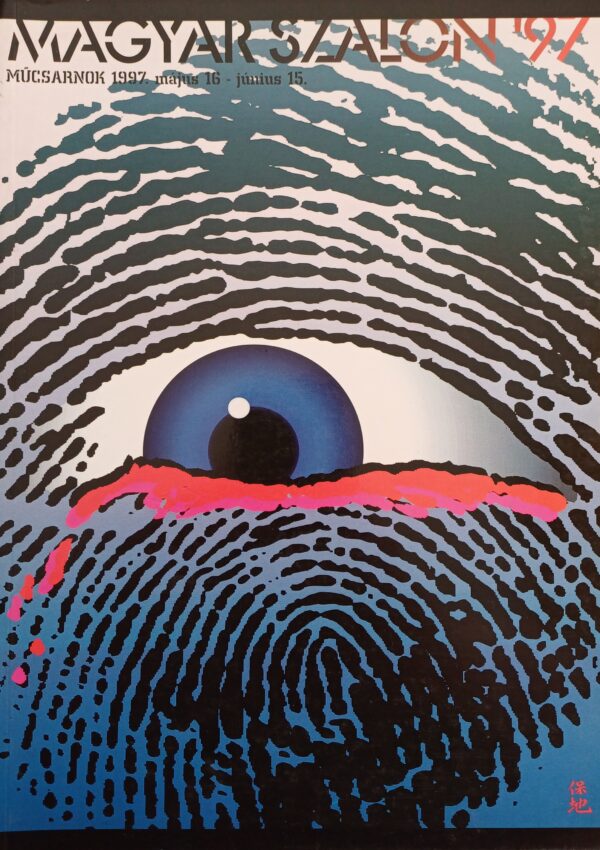

In February 1996, Gerzson wrote a letter to Beke, informing him that the Association had attracted significant sponsorship to organize a national salon exhibition in the building to celebrate the anniversary. The concept was rejected by Beke, but after the Association made its correspondence with the director public, the issue of the “National Salon” become a political scandal and part of the culture war discourse. Most conservative newspapers promoted a very simplified narrative, claiming that the Kunsthalle represents only a small group of Hungarian artists among a disproportionately large number of foreign artists. Moreover, some conservative and far-right affiliated artists and journalists specifically identified Beke and the Kunsthalle with the liberal political faction.52 In 1997, Bálint Magyar, the minister of culture of the socialist-liberal coalition, convinced László Beke to accept holding the exhibition in the building.53 The exhibition, entitled Hungarian Salon, finally took place in 1997, but the management of the Kunsthalle stated in a press release that the institution was not the organizer of the show, but merely providing the space for it.54

In addition to the salon-debate, many discussions took place about the rehabilitation exhibitions of the avant-garde, and the political engagement of avant-garde art in the pre-1989 system. In the heat of the debates, some artists and theorists exaggerated their pre-1989 grievances and their actual role in the regime change, or concealed the fact that they were, to a greater or lesser extent, an integral part of the pre-1989 system. Those who did not have such capital often did the opposite: they tried to relativize the earlier oppression of avant-garde artists and their relationship to political opposition groups. One of the most noticeable examples of this was the report titled “Ostracized Artists – Let the Kunsthalle Finally Become the Stronghold of Hungarian Artists,” published by the right-wing affiliated Magyar Demokrata (Hungarian Democrat).55 The report drew a parallel between the Kunsthalle under Beke’s leadership and state-socialist censorship. Furthermore, the article not only questioned the marginalization of avant-garde artists in the former era, but also depicted them as collaborators.56

At the end of the 1990s, the strong institutional preference for avant-garde art and the Kunsthalle’s rehabilitation-type exhibitions faced criticism even within the subfield of contemporary artists and theorists. Edit András, one of the leading promoters of feminist and gender theories in Hungary, never explicitly criticized Beke’s Kunsthalle. However, she frequently condemned the persistence of modernism in Hungarian art, arguing that it failed to provide space for younger artists following gender or feminist tendencies. This criticism was also relevant to the Kunsthalle’s exhibition policy.57 While avant-garde exhibitions remained a focal point at the Kunsthalle under Beke’s directorship, the institution’s programming did not prominently feature art dealing with the body, gender, feminism, postcolonial theory, or other new critical theories and tendencies.58 In 1998, a long-running artistic debate took place regarding the presumed over-favoring of the avant-garde, initiated by a young art historian, János Sturcz, in his article “Message to the Masters.”59Later, Péter György, a key gatekeeper of contemporary art, stated that the Kunsthalle had become “the rehabilitation office of the Hungarian neo-avant-garde.”60

Even though the Hungarian Salon went ahead, the conflicts around the Kunsthalle did not come to an end. The debate reached its zenith during the 1998 election campaign and strengthened the ultraconservative wing of the Association. Gerzson resigned and Iván Szkok was elected as president. Szkok was a conservative artist, both aesthetically and politically. Before 1989, he was a member of the Association but did not hold a strong position within it. Although he had a solo exhibition at the Kunsthalle in the 1970s, he was often a target of art critics.61 Despite this, he became a well-known figure during the salon debates in the 1990s. Just before the 1998 parliamentary elections, in a newspaper close to the conservative faction, Szkok claimed that when he raised the problem of the Kunsthalle and the salon during an open discussion with the socialist prime minister Gyula Horn, the prime minister told him that “he should not be so Hungarian.”62 Although the discussion was not recorded, the statement become popular in the right-wing media during the campaign. In 1999, Szkok burned paintings in front of the Kunsthalle as a protest against Beke’s exhibition policy and accused the director of mismanagement.63 Paradoxically, Szkok’s election weakened rather than strengthened the Association’s position. He had a poor reputation even among conservative artists, and as a result of his election, some members left the organization. In fact, while the right-wing press referred to the Association as the largest and most important visual arts organization, only 200 members attended the board meeting where Szkok was elected.64

In 1998, FIDESZ – Fiatal Demokraták Szövetsége (Hungarian Civic Alliance), led by Viktor Orbán, won the parliamentary elections and formed a new government with two other conservative parties. Despite media pressure, the new minister of culture did not remove László Beke, but appointed a new director only after his mandate ended. Under the leadership of Júlia Fabényi, on the occasion of the 1000th anniversary of the founding of Hungary, the Kunsthalle organized several National Exhibitions in 2000 and 2001. The organization of these events was not handled by the Association, but by MAOE and the Federation of Hungarian Fine and Applied Arts Societies. The new director was not a supporter of salon exhibitions either. Just like Beke, Fabényi promoted curatorial exhibitions and did not seek to establish connections with the Association. Meanwhile, the Association took steps towards consolidation by replacing Szkok and creating a new interdisciplinary section for contemporary artists. Despite this, and throughout the 2000s, the organization was unable to establish a decisive position within the institutional system of visual arts. At the same time, the issue of salon-type exhibitions at the Kunsthalle largely disappeared from the agenda. The topic resurfaced only after 2010, following the reelection of the FIDESZ, when the new cultural policy implemented significant changes in the contemporary art institutional system.65

Conclusions

Art history written after 1989 in Hungary – much like in other parts of Eastern or Central and Eastern Europe – has predominantly focused on avant-garde or contemporary art, along with its networks, institutional structures, and exhibition histories. This narrative typically portrays the regime change as a moment of triumph, marking the rehabilitation of the avant-garde and the institutional takeover of contemporary art. However, such accounts overlook the history of the broader artistic field. In reality, while the transition did elevate the restricted field of artistic production, it also precipitated the collapse and privatization of the redistributive art system of state socialism, leaving many artists and cultural producers facing decline and unemployment. Thus, a comprehensive analysis of the art history of the transition must take into consideration that the regime change was not merely a story of winners, but of both winners and losers.

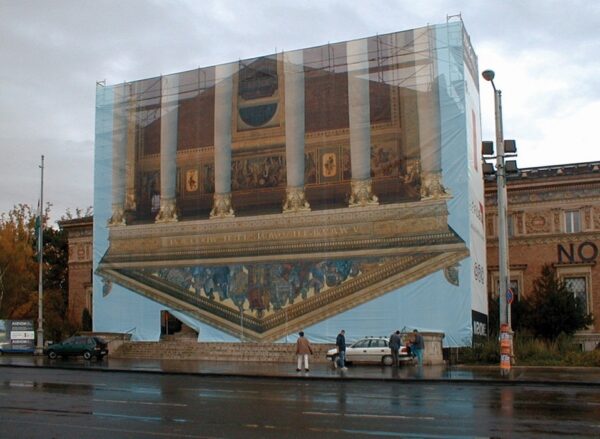

János Sugár: Nothing is like it used to be, 2002. Photo: János Sugár (with the permission of the Artist)

The fine and applied artists, along with other cultural workers represented by the National Association of Hungarian Artists (MAOE), faced economic challenges similar to those encountered by the working class in general. Many of them lost both their jobs and their market, and found themselves in a serious existential crisis. The artists primarily linked with the Association of Hungarian Fine and Applied Artists66 represented the declining middle class of the artistic community. The majority of these artists – despite being closer to the expectations of the general public than those active in the restricted field – had no real market demand, either before or after the political transition. Their livelihood primarily depended on symbolic capital, which they lost after 1989. By contrast, the Kunsthalle came to represent the new elite of the field: artists with strong symbolic capital. These artists were not interested in maintaining the Associations, but rather in the spread of privately-owned art galleries, rehabilitation exhibitions, and successful integration into the Western art world. The conflicts surrounding the Foundation were largely economic in nature, in contrast to the symbolic battles between the leadership of the Association and the Kunsthalle – which, of course, also had economic stakes: while the debates were primarily about representation, they were driven by the need for symbolic capital, which could later be transformed into economic capital.67

In post-socialist Hungary, the cultural cleavage line became the primary cleavage line68 of political battles, accompanied by intense political polarization.69 This significantly heightened the intensity of the conflicts within the field of cultural production. In the first years after the regime change, the primary cleavage line in the field of visual art was not a cultural one. However, the spread of the nationalist and market-liberal ideologies – along with increasing polarization in the political sphere and the rise of culture war discourse – gradually exerted a stronger influence on the field. Moreover, these conflicts were not only influenced but also manipulated and oversimplified by both politics and the media. As a result of these processes, the debate around the Kunsthalle and the salon increasingly took on the dynamics of political struggle: the actors in the restricted field of artistic production increasingly accepted the rhetoric of the market-liberal elites, while the Association – once established to create and propagate socialist realist art – gradually drifted towards a national-conservative protectionist policy.

Bibliography

András, Edit. “A Painful Farewell to Modernism: Difficulties in the Period of Transition.” In Omnia Mutantur, XXVII Venice Biennale, edited by Katalin Néray, 1997.

Attalai, Gábor. “Az iparművészet és ipari tervezőművészet helye és szerepe a mai magyar társadalomban” [On the Place and Role of Industrial Design in Contemporary Hungarian Society]. Művészet, no. 5 (1980).

Balogh, Gyula. “A művészeknek nem tartozunk elszámolással. A Magyar Alkotóművészeti Közalapítvány továbbra is nehéz helyzetben” [We Don’t Owe the Artists an Explanation: The Hungarian Creative Arts Foundation Remains in a Difficult Situation]. Magyar Hírlap, July 14, 1996.

Bánhidai, Károly, Balázs Feledy, and Ferenc Sinkovics, eds. “Kiutált képzőművészet – A Műcsarnok legyen végre a hazai művészek fellegvára” [Fine Artists Excluded – Let the Kunsthalle Finally Become the Stronghold of Hungarian Artists]. Magyar Demokrata, March 18, 1999.

Bertók László, Attila. “Könyékig az Alap kalapjában: Csak az SZDSZ barátai az igazi művészek?” [Up to the Elbows in the Fund’s Hat: Are Only the SZDSZ’s Friends the Real Artists?]. Magyar Demokrata, December 19, 1996.

Bojár, Iván. “Giccsek és álproblémák” [Kitsch and Pseudo-Problems]. Magyar Hírlap, August 15, 1974.

Bourdieu, Pierre. “The Field of Cultural Production, or: The Economic World Reversed,” Poetics 12, nos. 4–5 (1983): 311–356.

(devich). “Államtitkári botfülek” [Undersecretary’s Deaf Ears]. Magyar Nemzet, June 16, 1998.

Dippold, Pál. “Millecentenárium volt – A tét hatalmas: Rabok legyünk, vagy szabadok?” [There Was a Millennium – The Stakes Are Huge: Shall We Be Slaves or Men Set Free?]. Magyar Demokrata, 1996.

Drabancz, M. Róbert, and Mihály Fónai. A magyar kultúrpolitika története 1920–1990 [History of Hungarian Cultural Policy 1920–1990]. Debrecen: Csokonai, 2005.

Esanu, Octavian.Postsocialist Contemporary: The Institutionalization of Artistic Practice in Eastern Europe after 1989. Manchester University Press, 2021.

Esanu, Octavian. “What Was Contemporary Art?” ArtMargins 1 (2012): 5–28.

https://www.researchgate.net/publication/269617605_What_was_Contemporary_Art

Eyal, Gil, Iván Szelényi, and Eleanor R. Townsley. Making Capitalism Without Capitalists: The New Ruling Elites in Eastern Europe. Verso Books, 2001.

Fehér, Dávid. “Relations and Reality: Avant-Garde Artists and Applied Arts Beyond the 3Ts.” In Promote, Tolerate, Ban: Art and Culture in Cold War Hungary, edited by Cristina Cuevas-Wolf and Isotta Poggi, 57–70. Los Angeles: Getty Publications, 2018.

Fekete, Judit. “Művészek eltűnt milliói. Kóka Tamás menedzsercsapata jött, látott – és vitt…” [Missing Millions of the Artists: Tamás Kóka’s Management Team Came, Saw – and Took…]. Magyar Nemzet, December 10, 1994.

György, Péter. “A fal után” [After the Wall]. Élet és Irodalom, July 7, 2000.

Hajdu, Éva. “Új galéria nyílt meg a belvárosban” [A New Gallery Has Opened Downtown]. Magyar Nemzet, October 10, 1985.

Horváth, György.A művészek bevonulása – A képzőművészet politikai irányításának és igazgatásának története 1945–1992 (The Artists’ March – The History of Political Control and Administration of Fine Arts, 1945–1992). Budapest: Corvina, 2015.

Huth, Júliusz. “A menedzserkapitalizmustól a kultúrharcig – A képzőművész-szövetségek válsága a kilencvenes években” (From Managerial Capitalism to Culture War. The Crisis of Artists’ Associations in the 1990s). Kultúra és Közösség 2022/1: 53–67.

Huth, Júliusz. “Art Criticism in Hungary after 1989.” In Bridging the Gaps: An Anthology of Art Criticism in Central and Eastern Europe after 1989, edited by Jana Geržová et al., 29–33. Kraków: AICA Polska, 2023.

Huth, Júliusz.Magyar szalon. A képzőművészeti intézményrendszer átalakulása a rendszerváltás folyamatában és a mező főbb konfliktusai az 1990-es években (Hungarian Salon. The Transformation of the Institutional System of Fine Art in the Process of the Regime Change and the Main Conflicts of the Artistic Field in the 1990s). PhD diss., Eötvös Loránd University, Budapest, 2023.

Huth, Júliusz. “Képzőművészeti viták és kritikák az 1980-as években” (Artistic Debates and Art Criticism in the 1980s). In Kiállítások és kritikák – Képzőművészeti diskurzusok az 1980-as években, edited by Júliusz Huth and Kristóf Nagy, 17–67. Budapest: Szépművészeti Múzeum – KEMKI, 2024.

Huth, Júliusz. “Beyond the 3 Ts: Promote, Tolerate, Ban – Art and Culture in Cold War Hungary/Book Review.” ArtMargins Online, February 24, 2021.

https://artmargins.com/beyond-the-3-ts-promote-tolerate-ban-art-and-culture-in-cold-war-hungary/

Kácsor, Adrienn. Patronizing Contemporary Painting in State-Socialist Hungary. MA thesis, Central European University, Budapest, 2013.

Kitschelt, Herbert, Zdenka Mansfeldova, Radosław Markowski, and Gábor Tóka. Post-Communist Party System: Competition, Representation and Inter-Party Cooperation. Budapest: Central European University, 1999.

Kováts, Albert. “Művészeti élet és demokrácia” [Artistic Life and Democracy]. ARTforum – Információs bulletin, no. 2 (1998); and Új Művészet, no. 10 (1998).

Lelkes, Péter. “Savanyú a felismerés” [A Sad Realization]. Hírlevél [Newsletter], no. 1 (1996).

Lipset, Seymour Martin, and Stein Rokkan. Party Systems and Voter Alignments: Cross-National Perspectives. New York: The Free Press, 1967.

Mélyi, József. “Közép-európai Központ? A Műcsarnok öt éve: Interjú Beke Lászlóval” [Central European Centre? The Last Five Years of the Kunsthalle: An Interview with László Beke]. exindex.hu, August 15, 2000. http://exindex.hu/index.php?l=hu&page=3&id=710.

Menyhárt, László. “Ki támogat kit, hogyan és mi végre” [Who Supports Whom, How, and What at Last?]. Művészet, no. 11 (1979).

Molnár, Mária L. “Jelentéscsapdák: Beszélgetés Beke Lászlóval” [Meaning Traps: A Conversation with László Beke]. Új Művészet, no. 12 (1998).

Nagy, Kristóf. “From Fringe Interest to Hegemony: The Emergence of the Soros Network in Eastern Europe.” In Globalizing East European Art Histories: Past and Present, edited by Beáta Hock and Anu Allas, Routledge, 2018.

Nagy, Kristóf. “Rabinec Studio: The Commodification of Art in Late Socialist Hungary.” In Contemporary Art and Capitalist Modernization: A Transregional Perspective, edited by Octavian Esanu, 139–152. London: Routledge, 2020.

Nagy, Kristóf. “Whose Land, Their Art? Debates over the Tendencies Exhibition Series (1980–1981).” ArtMargins Online, October 19, 2020.

https://artmargins.com/whose-land-their-art-debates-over-the-tendencies-exhibition-series-1980-81/

Nagy, Kristóf, and Márton Szarvas. “Left Turn – Right Turn: Artistic and Political Radicalism of Late Socialism in Hungary. The Orfeo and the Inconnu Groups.” Contradictions: A Journal for Critical Thought 5, no. 2 (2021): 57–85.

Németh, Lajos. “Proposal to Reorganize the Association.” In Bridging the Gaps: An Anthology of Art Criticism in Central and Eastern Europe after 1989, edited by Jana Geržová et al., 139–143. Kraków: AICA Polska, 2023.

Rieder, Gábor. A magyar szocreál festészet története 1949–1956: Ideológia és egzisztencia [The History of Hungarian Socialist Realist Painting 1949–1956: Ideology and Existence]. PhD diss., Eötvös Loránd University (ELTE), Doctoral School of Art History, 2011.

Sturcz, János. “Message to the Masters: On the Problems of Assessment and Self-Evaluation.” In Bridging the Gaps: An Anthology of Art Criticism in Central and Eastern Europe after 1989, edited by Jana Geržová, Júliusz Huth, Małgorzata Kaźmierczak, Kata Balázs-Miklós, Arkadiusz Półtorak, Vlasta Ciháková, and Magdalena Ujma. Kraków: AICA Polska, 2023.

Székely, Katalin, ed.Rebels: Little Warsaw (András Gálik, Bálint Havas). Budapest: tranzit.hu, Kassák Foundation, 2017.

Szelényi, Iván. “Menedzser-kapitalizmus – A gazdasági intézményrendszer és a társadalmi struktúra változásai a poszt-kommunista átalakulás során” (Managerial Capitalism: Changes in Economic Institutions and Social Structure in the Post-Communist Transition). Lettre 19 (Winter 1995): 21–29.

Szikszai, Károly. “Alapítványi párhuzamok (1992–1996)” [Foundation Parallels, 1992–1996]. Élet és Irodalom, July 7, 1996.

T.B. “Négy év fogház Zemplényinek” [Four Years in Prison for Zemplényi]. Népszabadság, May 28, 1998.

Volume 12. Issues 4-5, 311-356.

Katalin Székely: Rebelling Discourses – Notes on Little Warsaw’s Rebels 4-13., The Student Revolt at the Hungarian Academy of Fine Arts, 1990. 16-26., 38-55., 152-168., 256-259., 438-444., Chronology: 490-499., Little Warsaw (András Gálik, Bálint Havas), Katalin Székely (ed.): Rebels, tranzit.hu, Kassák Foundation, Budapest, 2017.

- According to Pierre Bourdieu, fields of cultural production are relatively self-regulating social subsystems that possess a certain degree of autonomy from external influences – particularly religious and political ideologies, as well as market forces and other forms of power constraints. Advancement within the field of cultural production is determined not only by inherited economic, cultural, and social capital, but also by the symbolic capital acquired within the field. Over time, this symbolic capital can be converted into economic profit. Pierre Bourdieu, “The Field of Cultural Production, or: The Economic World Reversed,” Poetics 12, no. 4–5 (1983): 311–356. ↩︎

- Within the field, one can distinguish the field of ”mass-audience production” and the field of “restricted production”, in which producers strive for a higher level of autonomy and usually create art for other producers. The art produced in the restricted production field is often inaccessible to the wider public, but this field symbolically dominates both the artistic field and the institutional system. Bourdieu, “The Field of Cultural Production,” 320. ↩︎

- Júliusz Huth: Magyar szalon. A képzőművészeti intézményrendszer átalakulása a rendszerváltás folyamatában és a mező főbb konfliktusai az 1990-es években (Hungarian Salon. The Transformation of the Institutional System of Fine Art in the Process of the Regime Change and the Main Conflicts of the Artistic Field in the 1990s). PhD dissertation, Eötvös Lóránd University, Budapest, 2023. ↩︎

- Octavian Esanu, “What Was Contemporary Art?” Art Margins, no. 1 (2012): 5–28, 14. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/269617605_What_was_Contemporary_Art ↩︎

- In the early 1980s, as a result of the economic crisis, numerous reforms were introduced in Hungary, paving the way for the commercialization of cultural institutions. Drabancz, M. Róbert and Mihály Fónai, A magyar kultúrpolitika története 1920–1990 (History of Hungarian Cultural Policy 1920–1990). Debrecen: Csokonai, 2005, 64. ↩︎

- Művészet (Art), 1979/10, 9. ↩︎

- The “small galleries” were established in the 1970s at the initiative of the Visual Department of the Institute of Civic Cultivation and to support amateur artists. During the 1980s, some of these galleries – such as the Liget Gallery and the Óbuda Cellar Gallery – became important hubs for underground or alternative art of the time. ↩︎

- The Kiállítási Intézmények was similar to the Centralne Biuro Wystaw Artystycznych (Central Bureau for Art Exhibitions) in Poland. ↩︎

- There is no consensus in the Hungarian literature on the name of the avant-garde art of the 1960s and 1970s. Some Hungarian art historians refer to the abstract art of progressive modernity as neo-avant-garde, while others use the term exclusively for artists engaged in social criticism, action-based art, and conceptual tendencies. ↩︎

- Kristóf Nagy, “Whose Land, Their Art? Debates over the Tendencies Exhibition Series (1980-1981),” ArtMargins Online, October 19, 2020. ↩︎

- This was actually of great significance, as the Art Fund was profitable precisely due to this non-artistic activity. ↩︎

- According to Dávid Fehér, in the 1970s, like most Hungarian avant-garde artists, Gábor Attalai led a “double life.” On one hand, he created conceptual works that were rarely or never exhibited in official institutions in Hungary, and on the other hand, he was one of the most well-known and state-supported applied artists of the Kádár era. Dávid Fehér, “Relations and Reality. Avant-garde Artists and Applied Arts beyond the 3Ts,” in Promote, Tolerate, Ban: Art and Culture in Cold War Hungary, ed. Cristina Cuevas-Wolf and Isotta Poggi (Los Angeles: Getty Publications, 2018), 57–70, 58. ↩︎

- Gábor Attalai, “Az iparművészet és ipari tervezőművészethelye és szerepe a mai magyar társadalomban” (On the Place and Role of Industrial Design in Contemporary Hungarian Society), Művészet, no. 5 (1980). ↩︎

- László Menyhárt, “Ki támogat kit, hogyan és mi végre” (Who Supports Whom, How and What at Last?) Művészet, no. 11 (1979): 26–29. ↩︎

- Adrienn Kácsor: Patronizing Contemporary Painting in State-Socialist Hungary (MA Thesis, CEU, Budapest, 2013). ↩︎

- Éva Hajdu, “Új galéria nyílt meg a belvárosban” (A New Gallery Has Opened Downtown) Magyar Nemzet, October 10, 1985, 4. ↩︎

- Despite the political thaw, until the last third of the decade there were still topics considered taboo. These included questioning the presence of Soviet troops in Hungary and classifying the events of 1956 as a revolution. ↩︎

- Júliusz Huth, “Képzőművészeti viták és kritikák az 1980-as években” (Artistic Debates and Art Criticism in the 1980’s), in Kiállítások és kritikák – Képzőművészeti diskurzusok az 1980-as években, edited by Júliusz Huth and Kristóf Nagy (Budapest: Szépművészeti Múzeum – KEMKI, 2024), 17–67. ↩︎

- György Horváth, A művészek bevonulása – A képzőművészet politikai irányításának és igazgatásának története 1945-1992 (The Artists’ March – The History of Political Control and Administration of Fine Arts, 1945–1992) (Budapest: Corvina Kiadó, 2015). ↩︎

- The history of the Art Fund is thoroughly reconstructed up to 1989 in the book written by György Horváth. However, the archives of the Fund and its successor organizations were lost. In my PhD dissertation, I partially reconstructed the history of the successor organizations of the Fund by using scattered materials found in the MAOE office, the organization’s newsletters, and articles published in the press. Additionally, since the Foundation remained under state supervision, I also used materials from the State Audit Office and documents published in the Hungarian Official Gazette. ↩︎

- A Kormány 117/1992. (VII. 29.) Korm. rendelete a Magyar Köztársaság Művészeti Alapjának megszüntetéséről és a Magyar Alkotóművészeti Alapítvány létesítéséről [Government Decree 117/1992 (VII. 29.] on the termination of the Art Fund of the Hungarian Republic and the establishment of the Hungarian Creative Artists Foundation). Művelődési Közlöny. A Művelődési és Közoktatási Minisztérium hivatalos lapja (Cultural Bulletin. The official journal of the Ministry of Culture and Education). 1992.10.18. XXXVI. évfolyam, 16. szám, 807. ↩︎

- The Fund members were also writers and musicians. In 1989, the number of fine and applied artist members was approximately 5,000. ↩︎

- Not only the representative exhibition spaces and artists’ houses, but also the only supposedly profitable company, Art Retail Company, was running a deficit. The leadership of the Foundation and MAOE made numerous attempts to make the institution profitable, yet despite having several representative galleries in Budapest and in various other major cities, it ultimately went bankrupt in the 2000s. ↩︎

- Az Állami Számvevőszék Vizsgálatai. Összefoglaló a Magyar Alkotóművészeti Közalapítvány ellenőrzéséről/0323 (State Audit Office Investigations. Summary of the Audit of the Hungarian Creative Artists Foundation/0323). Hivatalos Értesítő – A Magyar Közlöny melléklete(Official Bulletin – Annex to the Hungarian Official Gazette). Budapest, 2003.10.22. VI. Évfolyam, 2003/43, 2005-2006. ↩︎

- Iván Szelényi, “Menedzser-kapitalizmus. A gazdasági intézményrendszer és a társadalmi struktúra változásai a poszt-kommunista átalakulás során” (Managerial Capitalism. Changes in Economic Institutions and Social Structure in the Post-Communist Transition), Lettre, no. 19 (Winter 1995): 21–29. ↩︎

- T.B., “Négy év fogház Zemplényinek” (Four years in prison for Zemplényi). Népszabadság, May 28, 1998, 21. ↩︎

- Jelentés a Magyar Alkotóművészeti Közalapítvány gazdálkodásának ellenőrzéséről. (Report on the Audit of the Hungarian Creative Artists Foundation’s Financial Management). Állami Számvevőszék (State Audit Office). 0323. 2003/6. ↩︎

- Judit Fekete, “Művészek eltűnt milliói. Kóka Tamás menedzsercsapata jött, látott – és vitt…” (Missing Millions of the Artists. Tamás Kóka’s Management Team Came, Saw - and Took…), Magyar Nemzet, December 10, 1994, 14. ↩︎

- Károly Szikszai, “Alapítványi párhuzamok (1992–1996)” (Foundation Parallels, 1992–1996), Élet és Irodalom, July 7, 1996, 4–6. ↩︎

- The June 1993 Newsletter of MAOE-MAA reports on a 1991 summary of visual arts income sent to the Ministry of Culture, which indicated that 57% of Foundation members earned only a gross annual income of 100,000 forints, which was considered below the subsistence level at the time. Only 30% of them earned the average income of a gross 200,000 forints. ↩︎

- Gyula Balogh, “A művészeknek nem tartozunk elszámolással. A Magyar Alkotóművészeti Közalapítvány továbbra is nehéz helyzetben (We Don’t Owe the Artists an Explanation. The Hungarian Creative Arts Foundation Remains in a Difficult Situation), Magyar Hírlap, July 14, 1996, 8. ↩︎

- Jelentés a Magyar Alkotóművészeti Közalapítvány gazdálkodásának ellenőrzéséről. (Report on the Audit of the Hungarian Creative Artists Foundation’s Financial Management). Állami Számvevőszék (State Audit Office). 0323. 2003/6. ↩︎

- Unlike in the case of the successor organizations of the Fund, the archive of the Association is accessible for research. Among other materials, the documentation of the Association’s general assemblies can also be found at its headquarters in Budapest. ↩︎

- Record of the Special General Assembly of the Hungarian Association of Fine and Applied Artists, held on September 21, 1989. MKISZ Archive. Közgyűlés: Rendkívüli (1989. szept.). XIII (1990. máj.) ↩︎

- Horváth, A művészek bevonulása, 39. ↩︎

- As evidenced by the attendance sheets, during the years of the regime change, artists and art historians who supported avant-garde or alternative art also attended the general assemblies. However, the number of these actors gradually declined over time. ↩︎

- Huth, “Beyond the 3 Ts.”. ↩︎

- Lajos Németh, “Proposal to Reorganize the Association,” in Bridging the Gaps: An Anthology of Art Criticism in Central and Eastern Europe after 1989, ed. Jana Geržová, Júliusz Huth, Małgorzata Kaźmierczak, Kata Balázs-Miklós, Arkadiusz Półtorak, Vlasta Ciháková, and Magdalena Ujma (Kraków: AICA Polska), 139–143. ↩︎

- Katalin Székely: Rebelling Discourses – Notes on Little Warsaw’s Rebels 4-13., The Student Revolt at the Hungarian Academy of Fine Arts, 1990. 16-26., 38-55., 152-168., 256-259., 438-444., Chronology: 490-499., 343. Little Warsaw (András Gálik, Bálint Havas), Katalin Székely (ed.): Rebels, tranzit.hu, Kassák Foundation, Budapest, 2017. ↩︎

- Jegyzőkönyv az 1995. május 31-i MKISZ Közgyűlésről. Közgyűlés: XIV. (1992. jún.) XV. (1995. máj.) XVI. (1998. máj). (Minutes of the General Assembly of 31 May 1995 In. General Assembly XIV [June 1992] XV [May 1995] XVI [May 1998]. ↩︎

- Albert Kováts, “Művészeti élet és demokrácia” (Artistic Life and Democracy) ARTforum – Információs bulletin 2 (1998): 2–4; also published in Új Művészet 10 (1998): 39–41. ↩︎

- Péter Lelkes, “Savanyú a felismerés” (A Sad Realization). Hírlevél (Newsletter), no. 1 (1996): 2. ↩︎

- Hírlevél (Newsletter), no. 2 (1998). ↩︎

- Hírlevél (Newsletter), August 1993. ↩︎

- Rieder Gábor, “A magyar szocreál festészet története 1949–1956 – Ideológia és egzisztencia” (The History of Hungarian Socialist Realist Painting 1949–1956 – Ideology and Existence) (PhD diss., Eötvös Loránd University, Doctoral School of Art History, 2011), 13. ↩︎

- Octavian Esanu, “What Was Contemporary Art?,” ArtMargins 1, no. 1 (2012): 14. ↩︎

- In English texts, the name of the organization is usually translated as “Union,” although the organization never really operated as a union. Before 1989, both “Association” and “Union” were used in English version, but since 1989 it has consistently used the term “Association”https://mkisz.hu/association-hungarian-fine-applied-artists/. ↩︎

- Kristóf Nagy, “From Fringe Interest to Hegemony: The Emergence of the Soros Network in Eastern Europe,” in Globalizing East European Art Histories: Past and Present, ed. Beáta Hock and Anu Allas (New York: Routledge, 2018). ↩︎

- Júliusz Huth, “Art Criticism in Hungary after 1989,” in Bridging the Gaps, 29–33. ↩︎

- The FIDESZ (Alliance of Young Democrats), founded in 1988 under the leadership of Viktor Orbán, began as a liberal party but gradually shifted to the right after the 1994 elections, eventually becoming Hungary’s leading right-wing conservative party. ↩︎

- Pál Dippold, “Millecentenárium volt – A tét hatalmas: Rabok legyünk, vagy szabadok?” (There Was a Millennium – The Stakes Are Huge: Shall We Be Slaves or Men Set Free?). Magyar Demokrata, 1996, 10-15. ↩︎

- Attila Bertók László, “Könyékig az Alap kalapjában. Csak az SZDSZ barátai az igazi művészek?” (Up to the Elbows in the Fund’s Hat. Are Only the SZDSZ’s Friends the Real Artists?). Magyar Demokrata, December 19, 1996, 18–21. ↩︎

- József Mélyi, “Közép-európai Központ? A Műcsarnok öt éve. Interjú Beke Lászlóval” (Central European Centre? The Last Five Years of the Kunsthalle. An Interview with László Beke), exindex.hu August 15, 2000, http://exindex.hu/index.php?l=hu&page=3&id=710 ↩︎

- Új Művészet (New Art), 1997/5-6, 2. ↩︎

- Károly Bánhidai, Balázs Feledy, Ferenc Sinkovics (comp.), “Kiutált képzőművészet – A Műcsarnok legyen végre a hazai művészek fellegvára” (Fine Artists Excluded – Let the Kunsthalle Finally Become the Stronghold of Hungarian Artists). Magyar Demokrata March 18, 1999, 8–13. ↩︎

- In the article, the sculptor Miklós Melocco stated that before 1989, “many abstract artists were in fact members of the Communist Party.” The statement was not substantiated, which was characteristic of articles dealing with the conflict between the Kunsthalle and the Association. However, it significantly contributed to deepening the debate surrounding the institution. ↩︎

- Edit András, “A Painful Farewell to Modernism. Difficulties in the Period of Transition,” in Omnia Mutantur, XXVII Venice Biennale, ed. Katalin Néray (1997), 26–29. ↩︎

- In an interview published in 1998, L. Molnár Mária asked Beke for his opinion on “new tendencies,” specifically psychoanalytic and feminist approaches. Beke gave a clearly dismissive response, calling these perspectives Marxist and describing them as practices that fall outside the realm of art. Mária L. Molnár, “Jelentéscsapdák. Beszélgetés Beke Lászlóval” (Meaning Traps. A Conversation with László Beke). Új Művészet, no. 12 (1998): 41. ↩︎

- János Sturcz, “Message to the Masters. On the Problems of the Assesment and Self-Evaluation,” in Bridging the Gaps, 220–228. ↩︎

- Péter György, “A fal után” (After the Wall). Élet és Irodalom, July 7, 2000, 22. ↩︎

- Iván Bojár, “Giccsek és álproblémák” (Kitsch and Pseudo-Problems), Magyar Hírlap, August 15, 1974. ↩︎

- (devich), “Államtitkári botfülek” (Undersecretary’s Deaf Ears), Magyar Nemzet, June 16, 1998, 9. ↩︎

- By „mismanagement,” Szkok referred to what he saw as Beke’s inadequate leadership of the institution. This accusation was particularly problematic because „mismanagement” can also be understood as a legal category, implying potential financial or administrative misconduct. The case eventually led to legal proceedings, which Beke ultimately won. ↩︎

- Jegyzőkönyv kivonat a Magyar Képzőművészek és Iparművészek Szövetsége 1999. június 15-én megtartott tisztújító közgyűléséről (Summary of the Minutes of the Election General Assembly of the Hungarian Association of Fine and Applied Arts, held on June 15, 1999). MKISZ székház archívum. “Közgyűlés: XVIII. (1999. jún.) XIX. (2000. máj.)” ↩︎

- In 2013, the leadership of the Kunsthalle came under the control of the Hungarian Academy of Arts (MMA). This decision sparked strong resistance from the Hungarian contemporary art community. Artists, curators, and other intellectuals argued that the MMA’s takeover threatened artistic freedom and pluralism. Despite numerous protests, the conservative government carried out a comprehensive institutional takeover and gradually dismantled the institutional system of critical and/or contemporary art in Hungary. http://www.kivultagas.hu/dokumentacio/ ↩︎

- Several artists were members of both associations. ↩︎

- According to Pierre Bourdieu, such struggles take place from time to time within artistic fields between producers working for different markets, and although they initially seem to be fought over purely symbolic stakes, economic stakes must also be recognized behind them. Bourdieu, “The Field of Cultural Production,” 311–356. ↩︎

- Seymour Martin Lipset and Stein Rokkan, Party Systems and Voter Alignments. Cross-National Perspectives (New York: The Free Press, 1967). ↩︎

- According to Herbert Kitschelt (et al.) the same happened in Poland: “Because Polish and Hungarian politicians cannot polarize electoral competition around economic issues in the face of reformist post-communist parties that embrace essentials of market capitalism, they have succedent incentives to construct a single powerful socio-cultural divide on which to display meaningful programmatic differences and employ dose to attract voters.” Herbert Kitschelt et al., Post-Communist Party System – Competition, Representation and Inter-Party Cooperation. Central European University(Budapest: Central European University Press, 1999), 267. ↩︎

Júliusz Huth

Júliusz Huth is a Budapest-based art historian specializing in the history of institutions, exhibitions, and visual art-related discourses in the second half of the 20th century, particularly in Hungary during the 1980s and 1990s. Currently, he is a researcher at the Central European Research Institute for Art History (KEMKI) and a lecturer at the Hungarian University of Fine Arts. He studied at Babes-Bolyai University in Cluj, Romania, and at Eötvös Loránd University in Budapest, Hungary. In 2024, he completed his PhD at the Eötvös Loránd University. He is also active as an art critic and is a member of the Hungarian Section of AICA.