Title

East Germany Comes to New York The 1993 SoHo Venture of Leipzig’s EIGEN + ART

https://doi.org/10.48285/ASPWAW.29564158.MCE.2024.10.17

Galerie EIGEN + ART, GDR, Gerd Harry Lybke, SoHo

https://miejsce.asp.waw.pl/en/east-germany-comes-to-new-york-the-1993-soho-venture-of-leipzigs-eigen-art/

Abstract

This article analyzes an initiative undertaken by the EIGEN + ART Gallery, founded in Leipzig in 1983 in the former German Democratic Republic (GDR), which involved opening a four-month branch in New York’s SoHo district. The branch operated in the spring of 1993, during a period marked by a severe crisis in the American art market and a deep recession in reunified Germany. The event was widely covered in the German media, which regarded it as an act of courage.

The study argues that EIGEN + ART’s success stemmed from the adaptation of strategies the gallery had developed and refined in Leipzig, where it functioned as an alternative exhibition infrastructure within a centrally planned, shortage-based economy. Transplanted into capitalist New York, these strategies included cost minimization—artists covered their own travel expenses and created or installed their works on-site. Strategic communication and thorough documentation also played a crucial role, exemplified by the professionally produced catalogue „We Are in New York”, which was intended more as a tool for image-building and reputation development than for direct sales.

Despite initial hesitation from the American art press, the project achieved significant visibility (including a mention in „The New York Times”). Participation in New York proved pivotal in establishing an international network of contacts, which contributed to the gallery’s later success—particularly as Berlin emerged as a contemporary art hub in the mid-1990s.

Keywords

Galerie EIGEN + ART, GDR, Gerd Harry Lybke, SoHo

DOI

Surviving in New York. Finding one’s niche in the shadow of skyscrapers. An artist’s dream. That dream turned SoHo into a village in Manhattan—the world capital of the art trade. To compete in this environment, one must offer something truly remarkable to the spoiled scene. No problem for Gerd Harry Lybke. Anyone who wrested the freedom for his private gallery, EIGEN + ART, from the GDR regime will not be intimidated by New York. Moreover, in an ironic market twist, rents along the Hudson have long since dropped below those on the Pleiße. So, the Saxons are coming, presenting the same Leipzig artists who, in the mid-1980s, exhibited in Lybke’s living room—while being eavesdropped on by the Stasi.

This quotation originates from a television report aired on heute journal on March 11, 1993. At the time, heute journal was one of the leading news programs in Germany’s public broadcasting system, reaching an audience of millions. The journalist Steffen Seibert was covering the opening of a four-month branch of Galerie EIGEN + ART—founded in Leipzig in 1983—in New York City’s SoHo neighborhood, and he asked whether this venture to America was a risky undertaking. The thirty-three-year-old gallerist Gerd Harry “Judy” Lybke responded confidently: “Yes, I think that perhaps this is one kind of courage a person can have. Running a gallery in Leipzig is just as courageous, in my opinion, as coming to New York and opening one here. And now, after this winter of recession, […] it’s something like the first sign of spring, when someone steps forward […] to invest again.”1

This television coverage was followed by extensive newspaper reporting in both regional and national German media. Der Tagesspiegel in Berlin, for example, wrote in April 1993: “His German colleagues threw up their hands in disbelief when it became known that Lybke, of all people, planned to open a branch gallery in the very center of the art market crisis—and at the height of a severe recession, no less. Yet the enterprising Leipzig gallerist seems almost energized by adverse circumstances: while the façades of SoHo are plastered with signs reading ‘Gallery room for rent,’ he is moving into the legendary Prince Building, directly across from the downtown outpost of the Guggenheim Museum. There, he could choose from among several lofts. For the once-coveted Broadway address is now home to just two galleries, one of them belonging to the famous dealer Leo Castelli.”2

Photographic documentation of the exhibition series We are in New York, March 11 to June 26, 1993, color photograph, original print, photographer unknown, AGEA, call number: A-1993-1280. Courtesy of the Archive Galerie EIGEN + ART Leipzig/Berlin. View from the exhibition space on the eleventh floor of the Prince Building, corner of Broadway, looking downtown toward the former Twin Towers.

The widely read weekly newspaper DIE ZEIT expressed admiration: “Although seventy galleries disappeared from SoHo last season alone, this does not deter the East German gallery vanguard.”3 Yet the article also noted that “at times, it seems as if the success story of East German gallerist Gerd Harry Lybke appeals more to American tastes than does the art he exhibits.”4 The Berlin tabloid B.Z., by contrast, reported on concrete sales figures: “Summary of the cheerful opening night on March 11, with German wine, chips, and cheese bites: a well-attended gallery (including German business leaders, Met curator Sabine Rewald, and the SoHo scene), and five paintings sold for a total of $6,000.”5

This extensive media coverage in Germany also reflects how the economic situation of the time was perceived. New York—the city that, after World War II, had challenged the prominence of Paris and London in the art trade, particularly for modern and contemporary art—was described in the spring of 1993 as the “center of the art market crisis.” Indeed, the overall economic situation in the United States, and by extension the art market, was dire. In retrospect, the beginning of Democrat Bill Clinton’s presidency on January 20, 1993, marked the end of a prolonged period of economic stagnation that had persisted since the mid-1980s. In 1991, the U.S. economy had even contracted slightly, with a negative growth rate of –0.11%, accompanied by high unemployment (7.3% in 1992) and a significant federal budget deficit.6

The admiration that Galerie EIGEN + ART received in the German press must also be understood in the context of an even more profound economic crisis in the newly reunified Federal Republic of Germany.7 With the unification of the two Germanys on October 3, 1990, the country both dismantled the communist dictatorship of the German Democratic Republic (GDR) and dissolved an economic system that had been severely weakened by decades of war reparations to the Soviet Union and a failing socialist planned economy. The influential weekly Der Spiegel captured the severity of the situation under the headline A Picture of Misery: “In 1990, the former West German Republic still ranked internationally as the best-organized, most socially just, and wealthiest industrialized nation in the world: the unemployment rate stood at 6.4 percent, economic growth at 5.7 percent, and inflation at 2.7 percent. By 1993, just three years later, the situation had shifted dramatically: unemployment had climbed to 9.2 percent, many of the jobless were long-term, while inflation approached 4 percent. The economy was shrinking by 2 percent, and government coffers stood empty.”8

The prevailing economic crisis only partially explains the intense media attention surrounding the opening of EIGEN + ART in New York. When David Zwirner—the son of internationally renowned Cologne art dealer Rudolf Zwirner—opened his first gallery space in SoHo during the same period, the German media paid little attention. His launch earned neither headlines nor television coverage. This is all the more striking given Zwirner’s recognizable name in the contemporary art world and his decision to invest in a long-term New York location. That EIGEN + ART’s short-term outpost attracted such disproportionate attention was due to one key reason: it was an East German gallery—founded in the GDR, still headquartered in Leipzig, and comprised mainly of East German artists and staff —that had made its way to New York. It came from a region where economic conditions were even more precarious than those described by Der Spiegel for reunified Germany as a whole.

At the time, Galerie EIGEN + ART was not yet ten years old and had already experienced a turbulent history under the GDR dictatorship, followed by the upheaval of systemic transformation. Just three years before the gallery embarked on its New York venture, gallerist Judy Lybke had to borrow money to finance a modest four-day-appearance—as the first and only East German gallery—in the West German art fair Art Frankfurt in March 1990.9 While the gallery was able to open a second location in Berlin-Mitte, the center of East Berlin, in 1992, it still lacked the financial resources to meet the standard practices of the commercial art world. Unlike internationally operating galleries with multiple locations, EIGEN + ART neither covered artists’ airfare nor paid for transport, insurance, or magazine advertising. Instead, we argue, the gallery drew on strategies it had first invented and refined in Leipzig—particularly before German reunification—to stage the highly visible launch of its SoHo outpost.

This study uses the case of EIGEN + ART to show how exhibition and gallery practices originally developed under a communist regime (within the constraints of a scarcity-driven, centrally planned economy) could prove effective in a capitalist market system. To explore this apparent contradiction, we reconstruct the exhibition program and local conditions of the gallery’s New York venture in the spring of 1993 and analyze them in relation to the origins and operational practices of EIGEN + ART, a private gallery founded in Leipzig in 1983. Particular attention is given to the gallery’s communication strategies and networking practices.

Reconstructing the We Are in New York exhibition program relies primarily on media coverage and original interviews with those involved at the time, as the transatlantic correspondence from the 1990s has not been preserved. Communication during that period depended on landline telephones with answering machines and fax machines that used thermal paper. Daily phone calls and voicemail messages were not recorded, and the faxes have long since become illegible.10 In contrast, the gallery’s archive is remarkably extensive. It preserves and catalogs not only press and media reports, but also photographs, communication materials, and working documents from the 1980s. These archival sources, along with existing scholarship on the art and gallery scene in late East Germany, form the basis of this study.

“We Are in New York”

The recession of the early 1990s left a visible mark on New York’s art market. As noted at the outset, DIE ZEIT reported that seventy galleries disappeared from the SoHo scene in 1992 alone. Already in 1991, New York Times art critic Roberta Smith had described a significant wave of gallery closures in the neighborhood south of Houston Street. Hoping that what harmed the market might ultimately benefit art, Smith described a rapidly shifting gallery landscape in SoHo. She observed that lower rents enabled galleries from other areas to relocate to the city’s leading district for contemporary art, allowed those already in SoHo to move into larger, better-equipped spaces, and opened the door for entirely new players to enter the scene. This transformation was marked by a move away from multi-story, department store–like buildings near Broadway toward ground-floor spaces in the less renovated, often visibly rougher areas of SoHo’s southwestern quadrant—locations that offered more space, a stronger sense of identity, and increased foot traffic. At the same time, many galleries adopted a renewed commitment to younger artists and to process-oriented practices such as installation and conceptual art. Programs increasingly featured performances, readings, and film screenings—formats that, in their informality and experimental spirit, echoed the subcultural ethos of early 1970s SoHo and the East Village of the early 1980s.11

These shifts in the real estate landscape also benefited EIGEN + ART, which was able to secure the top floor of the building complex at 578 Broadway, at the corner of Prince Street. The eleventh-floor space had become available after the closure of the Lorence-Monk Gallery—one of the many galleries founded in the 1980s that ceased operations in the early 1990s.12 When the Leipzig-based gallery established its New York presence, the nine floors beneath it—in what had previously been considered a prime SoHo property—also stood vacant. Only the ground floor remained active, housing one of the three New York locations of the prestigious Leo Castelli Gallery. For over four decades, Leo Castelli both shaped and dominated the market for contemporary art, particularly in relation to abstract expressionism, minimalism and pop art.13 He represented such artists as Robert Rauschenberg, Andy Warhol, Frank Stella, and Bruce Nauman—figures whose works, by the early 1990s, regularly fetched seven-figure sums at auction and were prominently featured in museum collections across North America and Europe.

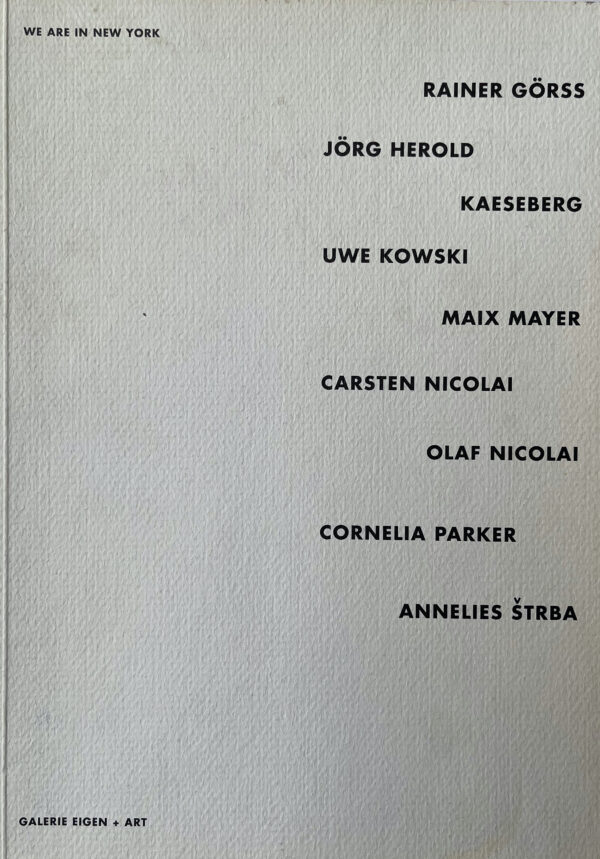

The group of artists presented by EIGEN + ART in its temporary eleventh-floor space—from March 11 to June 26, 1993—differed markedly from Castelli’s roster in terms of international visibility, market recognition, and inclusion in the canonical narrative of twentieth-century art. The exhibition program was structured in successive presentations, with participating artists traveling to New York for the duration of their respective shows.14 Of the nine artists featured, seven were male, around thirty years old, and born, raised, and trained in the GDR—that is, in a dictatorship behind the Iron Curtain, where citizens faced severe travel restrictions and the state controlled exchange with Western art centers. These artists included Rainer Görß (b. 1964), Jörg Herold (b. 1965), Kaeseberg (b. 1964), Uwe Kowski (b. 1963), Maix Mayer (b. 1960), Carsten Nicolai (b. 1965), and Olaf Nicolai (b. 1962). The two women in the program—both older and with more international exposure—were Cornelia Parker (b. 1956), who was born and trained in the United Kingdom, and Annelies Štrba (b. 1947), a Swiss artist who also lived and worked in Switzerland. What united all of them was that, at the time, none had works in museum collections, nor had any held a solo exhibition at a museum; while several had participated in group and gallery shows internationally, none of the artists had exhibited in New York prior to this presentation.15

The Leipzig-based gallery deliberately sought to establish links to the local contexts of the United States and the city of New York. The artist Christine Hill (b. 1968), born in Binghamton, New York, was, for example, appointed as “manager” of the gallery’s four-month East Coast presence. Gallerist Judy Lybke had met Hill in Berlin-Mitte in 1992 during one of her street performances, which she described as a “cheerful encounter with the German public in various service-oriented roles.”16 At the time, she handed out flowers free of charge to passersby in the center of former East Berlin, creating a moment of social and emotional exchange in return for her gesture: “Say it with flowers!”17 Hill also curated the final section of the exhibition series, which featured artists based in New York, including a performance by RAMM:ΣLL:ZΣΣ (b. 1960), an intermedia artist born in the city.18 In contrast to the European participants, however, the artist selection for the “New York Artists” segment had not been determined in advance, as evidenced by the exhibition catalogue printed in Leipzig prior to departure.19 While this program may have appeared ad hoc, it was in fact strategically designed—albeit with elements of improvisation. The gallery was pursuing an international agenda: to promote selected artists from the former GDR through global exposure and by positioning their work in dialogue with non-German perspectives.

For the New York debut of these artists, the gallery made no significant structural changes to the space—only a few racks were removed to create a working studio—and incurred no major expenses on site, aside from purchasing a fax machine.20 Unlike David Zwirner, who pursued a more long-term investment strategy, Lybke aimed to minimize costs amid the uncertainties of a crisis-ridden art market. The artists took care of the installation, including materials and transport of their works; they paid for their own flights and meals, and they usually arranged accommodations through friends and acquaintances in the East Village.21 These efforts to minimize expenses extended to artistic production itself. Transaction costs were kept low through the choice of materials—primarily paper—and by producing or assembling works on site. In a side room adjacent to the exhibition space, for example, Uwe Kowski completed his collages by cutting up pre-drawn charcoal sketches on paper and mounting them onto canvas.22 Carsten Nicolai created woodcuts using plywood sheets salvaged from trash, which he had sourced from abandoned buildings and construction sites along Broadway.23 His brother, Olaf Nicolai, arranged similar plywood supports and fabric panels with screen-printed cotton handkerchiefs that had been produced beforehand in Leipzig, bearing single words in German like “Aufbruch” (Departure) or “Ankunft” (Arrival)—direct references to key terms from President Bill Clinton’s inaugural address on January 20, 1993.24 EIGEN + ART’s approach to making, curating, and mediating art echoed the trend that critic Roberta Smith had described in her 1991 report on SoHo’s emerging, more experimental ground-floor galleries. Yet, this process-driven, more casual, and seemingly improvised artistic and curatorial approach stood in contrast to the gallery’s rented white-cube space in a high-rise on Broadway—and to the professionally printed, durational exhibition catalogue produced in Leipzig.

Cover of the Catalogue We are in New York. Rainer Görss / Jörg Herold / Kaeseberg / Uwe Kowski / Maix Mayer / Carsten Nicolai / Olaf Nicolai / Cornelia Parker / Annelies Štrba (Edition EIGEN + ART Leipzig, 1993), 57 pp., 29.5 × 21 cm, thread binding, print run 1,000, AGEA, call number: H-1993-270. Courtesy of the Archive Galerie EIGEN + ART Leipzig/Berlin.

The catalogue, produced explicitly for the gallery’s four-month New York outpost, proudly declared on its cover: We Are in New York.25 Published in an edition of 1,000 copies, it presented the five East German and two British or Swiss artists in alphabetical order. Reflecting its relatively large print run, the 57-page publication—approximately A4 in size—was printed using standard offset techniques. Its reinforced textured-cardboard cover, matte gray endpapers, and silk-finished off-white pages were all made from high-quality materials. Notably, the catalogue was thread-bound, a more elaborate and durable technique that underscored a commitment to permanence at odds with the improvised, process-oriented nature of the exhibition itself. Both the design and production quality of this catalogue exceeded what emerging galleries typically produced as ephemeral material for contemporary group exhibitions in the 1990s. The same holds true for the involvement of a translator and seven external art historians, critics, and artists as contributors for one-page essays introducing the work of the artists.26 While these authors might have been as unfamiliar to the New York audience as the artistic positions they described, the scholarly ambition reflected in their contributions is nevertheless striking.

In the catalogue We Are in New York, the scholarly or artist-written essays introduced a sequence of five pages containing photographs of the respective artists’ works. These texts, however, offered theoretical contextualizations of individual artistic practices and did not explicitly reference the illustrations. The most recent artworks reproduced in the catalogue date from 1992, though the majority originated in the years 1990 to 1991. Works created prior to 1990 were also included for Carsten Nicolai and the two non-East German artists. The catalogue primarily featured large-scale spatial installations (by Rainer Görß, Jörg Herold, Carsten Nicolai, Olaf Nicolai, and Cornelia Parker), as well as sculptures and objects, together accounting for 23 of the 45 reproduced works. The remaining pieces comprised works on paper (many incorporating photography) and three canvases. In the catalogue images, artworks were typically photographed in artists’ studios or temporarily repurposed basement spaces. This aesthetic was more reminiscent of the recently popularized gallery spaces in SoHo’s southwestern quadrant or the rougher East Village—both described by Roberta Smith—than of the white-cube spaces that Galerie EIGEN + ART encountered on Broadway, emblematic of the better-funded segment of the New York gallery scene.

Taken together, the exhibition space, the artistic program, and particularly the catalogue We Are in New York highlight the apparent contradictions embedded in Galerie EIGEN + ART’s four-month SoHo venture. It may seem paradoxical—even absurd—that a professionally produced catalogue explicitly designed for this exhibition series did not depict works exhibited in New York, and also did not showcase recently created pieces that the art market typically values most. Furthermore, it offered limited practical value as a sales tool: none of the catalogue essays explicitly referenced specific artworks, and while the texts and biographies were translated into English, critical details like titles, media, and dimensions were, with the exception of Cornelia Parker’s works, provided only in German—an oversight limiting its practical utility for an English-speaking audience. This carefully crafted publication thus served less as a sales catalogue for potential New York buyers than as a form of strategic communication. Given the gallery’s limited financial resources amid an art market in recession, such an elaborate catalogue was arguably a deliberate luxury. This raises questions about the gallery’s motivations: did the artistic and curatorial program intentionally cater to contemporary New York trends, opportunistically seeking market recognition? Or, to put it more provocatively, did Galerie EIGEN + ART embody the American adage of “fake it until you make it,” presenting itself as more established or ambitious than it actually was? The gallery’s recent past tells a different story. Rather than mere market opportunism, its approach was shaped by traditions rooted in its origins in the GDR—traditions specific to Leipzig and that would prove resilient throughout the economic and ideological upheaval following 1989.

EIGEN + ART as an Alternative Infrastructure in 1980s Leipzig

The genesis of the Galerie EIGEN + ART, which emerged in Leipzig in the early 1980s, can only be understood and appreciated within the context of a dictatorship with a communist one-party system and a socialist planned economy. In the GDR, criticism of the state, as well as other statements or actions deemed to pose a threat to the state, were persecuted and suppressed by the authorities and functionaries of the Socialist Unity Party (SED), the People’s Police (Volkspolizei) and, in particular, the Ministry for State Security (Stasi). An omnipresent surveillance system consisting of official agents and unofficial informants actuated this repression by means of subtle methods that instigated professional discrimination, caused social isolation, or manipulated professional or private life; indeed, these techniques were so inconspicuous that those affected did not necessarily recognize their effects as state intervention.27 The GDR legal system had at its disposal a wide range of administrative offenses to prosecute its citizens, including offenses under the Criminal Code. If, for example, cultural activities were declared to be “anti-state agitation,” “public disparagement” or even “treason,” the accused were threatened with prison sentences; in the case of suspected espionage, even death sentences were theoretically possible.28

The GDR was a state that assigned a social function to art and culture, thereby appropriating this sphere in political and ideological terms.29 The guiding principle for GDR cultural policy issued from the project of Socialist Realism, which was proclaimed in the Soviet Union in 1934 and was used as a propaganda instrument of the state; however, Socialist Realism also articulated a utopian project that sought to enable immediate comprehensibility and accessibility for the general population in their encounters with art. Overall, however, it was less a uniform style than an ideological construct that could integrate different stylistic devices as long as they served the political function of art.30 Art and cultural activities were regulated and controlled by associations, in particular the Association of Visual Artists of the GDR (the Verband Bildender Künstler, or the VBK).31 The VBK only rarely admitted self-taught artists who had completed their qualifications through an independent study program; as a rule, members of the VBK had completed a creative or artistic degree, particularly at one of the three art academies in Berlin-Weißensee, Dresden or Leipzig, where admission standards were very high. In addition, a probationary period of three years before potential admission to the VBK served to ensure that candidates’ work was not too critical and did not deviate too far from the party’s cultural policies, whether in terms of style or content.32

Membership in the association constituted a prerequisite for being able to work and exhibit as an artist. Only members of the VBK could receive art awards and commissions, sell their works through the state-organized art trade or present them publicly in the exhibition, gallery and museum system, which was also organized by the state. Membership also meant that artists could purchase art supplies in specialized stores, which was an important source of supply in a planned economy such as the GDR, where there were sometimes shortages of the most basic materials. Even more important, however, was the tax number issued with membership, which made it possible to rent a studio for artistic purposes and and engage in independent professional work. Such authorization was essential, since those without permission to work independently—or without formal employment—risked prosecution under the so-called “asociality paragraphs” and a conviction could result in state-imposed re-education measures or even several years of imprisonment.33

However, as the economic and political crisis in the GDR intensified from the 1970s onwards, this system of state-controlled production and dissemination of art and culture was more and more actively undermined.34 This led many authorities and functionaries to adopt a more flexible approach regarding conduct critical of the state; this was also a response to the never-ending discontent among intellectuals, writers and artists following the politically motivated expatriation of the poet Wolf Biermann in 1976.35 However, the GDR’s social system also maintained options for seeking alternative forms of art production and dissemination. The GDR exported high-quality and marketable goods to the West; special goods, housing and services were allocated via state contacts or other relationships; and elementary needs and product groups such as basic foodstuffs, housing and local public transport were kept at the lowest price level through subsidies. This all meant that income levels hardly played a role in the quality of life or self-actualization.36 With the simplest hourly yet contractually regulated jobs – whether as a funeral orator, film projectionist or stoker – artists were able to finance everyday life while also avoiding being persecuted under the asociality paragraph. These side jobs, which required little in terms of time commitment or intellectual exertion, offered freedom for those who sought it.

This included Judy Lybke, who was dismissed as an instructor for “youth clubs” at the Leipzig-Southeast district council because he had used his office to facilitate performances by banned bands, singer-songwriters and writers.37 Beginning in 1983, he worked by the hour as a nude model at Leipzig’s Art Academy (Hochschule für Grafik und Buchkunst, or HGB) in Leipzig, and in evening classes he met “like-minded people who didn’t necessarily seem to like the clearly defined academic profile of artistic training.”38 This is where he met the artists Jörg Herold and Uwe Kowski, whose works were later shown in New York. The Plagwitz Interest Group (Plagwitzer Interessengemeinschaft, or PIG), founded by them and other young comrades-in-arms, began to produce art outside the university and eventually exhibited it in Lybke’s run-down attic apartment in south-central Leipzig.39 The first exhibition, entitled “The New Unconcrete” in April 1983, was followed by fifteen more before the group’s relocation in June 1985.40

The exhibitions, which took place roughly every four to six weeks, initially resembled day-long happenings and parties for a circle of friends. “In the ‘creative boredom’ of those years, a generation came together in the attic on Körnerplatz—apprentices, technical students and the ‘whole leisure crowd’, fresh from secondary school, students from the university and the theological seminary, drama students and young artists, many of them self-taught.”41 Exhibitions evinced very different aesthetic positions:

Some expressed their rebellion in ‘expressive brushstrokes,’ others operated with happenstance or provisional forms, or staged themselves as an expression of their feelings. The new gallery owner didn’t really care; he wasn’t interested in a new style of painting or a changed conception of sculpture—academy and genre were of little importance, devotion and respect for the artwork nothing—but it was all about creating a playful and communicative atmosphere alongside the exhibitions in which everyone could participate.42

Increasing numbers of visitors necessitated a search for other exhibition spaces.43 In the outlying Connewitz district of Leipzig, which at the time was in a state of dire disrepair, they were able to rent the vacant former workshop premises of Rohrer & Klingner Leipzig-Co., which had been a traditional specialist manufacturer of ink, India ink (tusche) and products for etching and lithography.44 The Säuberlich bookbindery—with which EIGEN + ART later produced art portfolios, boxes and book bindings over the next few years—was already located above the new exhibition rooms.45 Situated in a rear building with a courtyard, the new spaces were separated from one of Leipzig’s busiest streets by residential buildings (some of which were vacant) and, due to their location outside the city center, were hardly visible to the general public or walk-in customers. Judy Lybke rented the 65-square-meter space with the painter Akos Novaky (1951–2022), who was a member of the VBK and was thus able to legitimize the commercial space as a studio.46

Photographic documentation of the exhibition opening of “Meine Sprache der Fotografie” (My Language of Photography), Conceptual Photography 1980–1985 by Klaus Elle, held at the Workshop-gallery EIGEN + ART in Leipzig-Connewitz from February 14 to March 16, 1986, 1 black-and-white photograph, original print, photographer unknown. Courtesy of the Archive Galerie EIGEN + ART Leipzig/Berlin. Pictured: from left to right, Lutz Dammbeck, Klaus Elle, Judy Lybke, Christoph Tannert, and Michael Kuhnert, surrounded by visitors at the show.

Together with around fourteen other artists, Lybke and Novaky held a founders’ party (Stifterfest) on June 27, 1985, to mark the launch of the gallery. These co-founders, who were mostly association members in their 30s and 40s and therefore a good ten years older than the aspiring gallery owner, donated works of art for an auction to finance the new infrastructure.47 With the support of other young assistants, the rooms were renovated over the next four months and finally opened on October 25, 1985, as the EIGEN + ART Workshop-gallery with an exhibition by the founding artists.48 Fifty-two exhibitions were shown here at the Connewitz location in the time leading up to the opening of the GDR borders on November 9, 1989. The artistic program remained heterogeneous, initially focusing primarily on VBK artists—to demonstrate the harmlessness of the undertaking to party functionaries—while occasionally also exhibiting artists from other GDR regions. The works of self-taught artists were also shown, including Kaeseberg, Maix Mayer, Carsten and Olaf Nicolai, for example, who had never studied art and belonged to a new generation at the time.49

The new location in Connewitz took up what had been successful at the apartment at Körnerplatz: giving exhibitors and visitors a sense that they belonged to a loose community defined by its solidarity, and making exchange the overriding principle. However, the transformation to an increasingly public space did not unfold without conflict. Some had hoped that the Workshop-gallery would also function as a social model, just as the co-initiators’ hopes for a producers’ gallery with a programmatic focus were not fulfilled.50 Instead, Judy Lybke took the gallery in a specific direction by establishing regular opening hours as well as organizing and taking on constant, small-scale work. Karim Saab, author and editor of the alternative magazine Anschlag, who was directly involved with EIGEN + ART, described the process as follows:

In the beginning, the gallery owner Judy Lybke had to emancipate himself from the artists […]. He reduced to a realistic level the amount of sense and time that every artist was expected to invest in the publication of art. The unwritten statutes of Eigen+Art demanded no more and no less of the art producer than that he should look after his own exhibition. The artist himself had to manage the bulk of the exhibition work and was directly involved in the risk of the event. The gallerist took a back seat and was content to initiate the encounter between producer and recipient.51

Lybke set the exhibition calendar entirely on his own authority. Although he occasionally invited guest curators, probably to enable aesthetically linked group exhibitions, he successfully resisted the idea of an advisory committee. He argued that a predetermined circle was less open than Lybke himself, who asserted that he gave a say to anyone who passed through.52 The majority of the exhibitions were solo shows (33 of the 52 mentioned before November 1989) and therefore did not have a collective character, as the founders’ party insinuated, but were the result of bilateral agreements. Lybke had long since assumed the role of a gallery owner who offered a platform—and increasingly professional framing—to certain artistic positions that he himself selected according to his own taste.

One of the gallery’s central working principles revolved around the active involvement of experts. An art historian usually spoke at the exhibition openings in particular, placing the works on display in the context of contemporary art; important voices here were, for example, Klaus Werner (1940–2010), Gabriele Muschter (1946–2023) and Christoph Tannert (b. 1955). All three were trained art historians, VBK members of the art history section, connoisseurs of contemporary art, and supporters of abstract and non-conformist art as shown at EIGEN + ART. Werner in particular had repeatedly come into conflict with state authorities due to his commitment to art that was undesirable to the state. In 1964 he was dismissed from the Ministry of Culture, followed by his exclusion from the state-organized gallery system in 1981. Tannert lost his position at the VBK for similar reasons in 1984. As speakers at EIGEN + ART, they acted as mediators and advocates whose expertise helped to position and legitimize the gallery’s works as relevant contributions to contemporary art.

Although the gallery’s activities became increasingly professionalized during the Connewitz period, they retained the ambiguous name Workshop-gallery (Werkstatt-Galerie) EIGEN + ART. However, its designation as a workshop did not mean that visitors could look over the artists’ shoulders while they were working. If artists were creating physical works, they were at most finished on site, mounted or staged for the space—as is customary in contemporary galleries before an exhibition opening.53 The name was primarily intended to protect the venue from potential state intervention; because they had labelled EIGEN + ART as a workshop, the artists who came and went on a monthly rotation could appear as subtenants, and visitors as their guests. However, this is why it was so important that the exhibiting artists were present during opening hours, so that, should the worst case arise, they could credibly defend the idea that the gallery was an open studio. This legal necessity became a unique selling point of the gallery and contributed to its profile.54 It was a discussion workshop in which the artists, the gallery owner and all visitors could discuss what was on display, Karim Saab noted.55

What EIGEN + ART had thus established was an alternative exhibition infrastructure, with a regulated program, in Leipzig. At no time did the gallery want to give the impression of showing something decided or fixed, or as competing with the program of museums or other established GDR structures; instead, they sought to present artistic proposals and experiments for discussion. The underlying concept was not political commitment or a complete rejection of the socialist system, but rather the creation of a public platform that promoted self-determination in artistic expression and was able to communicate art and, in some cases, even its sale. EIGEN + ART was thus an actor within alternative culture and corresponded to the type of private gallery that emerged with increasing frequency in some places in the GDR, especially from the mid-1980s onwards.56 Apart from Judy Lybke’s enterprise, there were only about forty-two comparable private initiatives that had existed in the entire forty-year existence of the GDR, all of which had taken great risks with their unofficial involvement and differed significantly in their organization and activities.57 What made EIGEN + ART stand out most was the paper trail that was deliberately built up from the outset—meaning not just the gallery’s communication but also its documentation activities—and the above-average recognition that resulted from this, not least in the West.

EIGEN + ART’s Paper Trail and “Westkontakte”

From the beginning, EIGEN + ART sought to reach an audience that included more than just artists and their immediate circles. To extend their range beyond the informal networks among artists, the gallery had to resort to reproducible media so that they could communicate organizational and content-related information about the gallery program. One medium that was available to everyone, at least in a simple form—even in the ration-controlled economy of the GDR—was paper. There were also plenty of printing companies in the GDR, from small, artisan-run businesses to large printing houses, especially in Leipzig. Historically, Leipzig was the city of German book printing and trade, with the most important book fair since the end of the seventeenth century; with an art academy that, in keeping with its orientation, was renamed the Royal Academy of Graphic Arts and Book Trade in 1900; and with a graphic arts district where several thousand book and printing companies were located in the early twentieth century. Despite the ravages of the war, the introduction of a socialist planned economy, and the departure of major publishing houses, Leipzig retained its dominant position, at least within the severely restricted GDR. In particular, Leipzig’s Art Academy, which had been renamed the Academy of Graphic Arts and Book Design (Hochschule für Graphik und Buchkunst, or HGB) in 1950, continued to train highly specialized professionals for this sector of the economy. Until the 1990s, the majority of HGB students concentrated on book art, photography, and graphic design; reproduction techniques remained central elements of the curriculum.58

Private entities such as EIGEN + ART were able to use this existing infrastructure for their communication purposes, at least to a limited extent. In the GDR, there was censorship which, although not officially designated as such, subjected printed matter above a certain print run to an approval procedure in order to control and, if necessary, prevent the dissemination of anti-state statements. There were differences, particularly with regard to print runs, because journalistic, literary, and artistic media, as well as text and image information, were treated differently.59 For example, in the 1980s, only up to five copies per typewritten page were permitted for the reproduction of literary texts. According to the fee schedule for fine arts, however, permission from the local state cultural authorities had to be obtained for print works exceeding 100 sheets.60 However, even if the maximum limits were observed, this did not mean that publications could not be banned if, for example, they were declared subversive; it merely meant that they did not have to be submitted to the authorities prior to production. Unlicensed publications could in principle be prosecuted as “illegal reproduction” and have both legal and secret service consequences. The alternative art and exhibition scene in the GDR knew how to exploit and continually expand the resulting scope for invitations and postcards, posters, portfolios, and books in limited editions.61 For EIGEN + ART, as for other private galleries, the production of communication materials initially arose from the practical need to communicate the title, dates, and location of an exhibition to potential visitors. Even in the early days, when artists were still exhibiting in Lybke’s apartment on Körnerplatz, invitation cards and at least two posters per year with the respective exhibition details were produced as unique pieces in various mixed artistic techniques by the exhibiting artists. With the move to the Connewitz courtyard and the increasing professionalization of EIGEN + ART, the number of posters produced annually increased disproportionately from 1986 onwards, sometimes exceeding the number of exhibitions per year because, for example, several artists supplied posters for group exhibitions.62 Judy Lybke and the artists he exhibited benefited not only from the changing cultural policy of the GDR in the 1980s, with its increasingly flexible interpretations, but also from Leipzig’s infrastructure; in some cases, they even benefited directly from their training in printmaking at the HGB.63

The posters, mostly produced using screen printing techniques, initially appeared in small, unknown print runs and were deliberately not placed in the cityscape in order to avoid the requirement for approval and not to provoke any administrative offenses that could be prosecuted by the state.64 The numerous EIGEN + ART posters always appeared on the occasion of an exhibition, even those that were purely artist posters and contained no practical information. These screen-printed posters were mostly produced by the artists themselves or at least according to their specifications in collaboration with printing workshops, such as Hartmut Tauer’s in Markkleeberg, south of Leipzig.65 In screen printing, a screen must be made for each color, through which the ink is applied to the paper with a squeegee. If there are three colors printed in the motif, three different screens are required, and after each of these printing processes, a drying time for the paper must be allowed for the next color. The effort involved explains why the artists used only one color (often black) for the majority of the poster designs for their exhibitions, i.e., only one screen. However, this limited color scheme did not detract from the posters’ status as works of art, and they were sold enthusiastically by the gallery to its visitors. The tradition of printing a poster for each exhibition was only discontinued in 1991, when, in reunified Germany with all its democratic freedoms of the press, the effort involved for the gallery and the artist was probably no longer in proportion to the degree of attention and potential sales revenue that could be achieved.66

In addition to posters, in the mid-1980s the gallery began publishing portfolios and bound books featuring prints by the artists exhibited there in increasingly larger but limited editions (up to 75 copies), using the name Edition EIGEN + ART from 1986 onwards. As with the posters, the artists were involved in the production process and collaborated with print shops specializing in graphic art. Linocuts and other printing techniques are found sporadically within these editions, but screen printing remained the main technique used for the majority of the portfolios and books published by EIGEN + ART in the GDR. As was customary for print artworks in the art market of the 20th century, the exact print run was communicated and there was often a limited number of special editions, which had been signed or painted over by the artist, for example, and thus justified a higher sales price. While the posters initially served mainly to cover expenses, the gallery’s brisk publishing activity enabled it to stand on solid financial footing at the end of the GDR.67

With the change of system and the abolition of the GDR licensing regulations, the publishing house Edition EIGEN + ART (now also equipped with an ISBN number) began to have exhibition catalogs produced mechanically in offset printing, with print runs regularly reaching 1,000 or 1,500 copies. These brochures and catalogs were no longer considered artistic works and mostly contained only texts and photographic reproductions of artworks. Apart from the more expensive special editions, which usually included an original print by the artist, the retail price ranged between 10 and 40 German marks, depending on the production costs, size, and number of illustrations. As Judy Lybke recalled in an interview, the income generated from these was “not huge, but it was enough for design and printing. We were able to publish our artistic ideas and concepts ourselves fairly quickly and didn’t have to wait for money to come in from a museum or a state funding program. As for the price tags on the catalogs, they were really just information that they had a value. We gave many of them away and saw them more as a gift that could be used to strike up conversations with other artists, curators, journalists, and even collectors.”68

In addition to financing and communication purposes, EIGEN + ART’s “paper trail” also fulfilled a third, central function: documentation. From the very beginning, Judy Lybke kept records of all activities, collected and preserved all possible EIGEN + ART printed materials, and archived his own and others’ texts as well as the gallery’s correspondence and business documents, regardless of how dilapidated the premises were, how spontaneous the programs were, and how much the quality depended on immediate exchange. Lybke’s keen sense of documentation is particularly evident in the elaborate annual documentation he began publishing in 1986, barely three years after his beginnings in the attic apartment.69 This was an elaborately produced graphic and documentary cassette that comprehensively documented the previous year. Each box, made of sturdy linen, contained an artistic work, made of paper, by each of the artists who had participated in the previous year and a bound text section in a linen cover with all the artists’ biographies, information on all the works shown that year, as well as texts, opening speeches, reviews, and photos of the artists and exhibitions. These activities alone meant that Lybke’s documentation surpassed what other private and even state galleries had achieved in terms of scope and quality.

However, the EIGEN + ART archive was unique in the GDR in another respect. Not only were cameras used to document all the works on display, but also a video camera, a device that recorded moving images and sound and was not manufactured for private use in the GDR, let alone sold in stores.70 Marianne Tralau (1935–2022), a West German artist working in Cologne at the time, gave Judy Lybke the video camera as a gift during a visit to the GDR in 1985.71 She was part of the left-wing, journalistic, and artistic video collective KAOS Film- und Video-Team and, starting in 1985, ran the associated KAOS Gallery in Cologne. The city-sponsored art initiative made a name for itself by exhibiting “unsellable art” and professionally filming and documenting artists and their work that was not particularly marketable, at least on video.72 Here, too, it seemed that what Karim Saab had noted about Lybke’s commitment had been put into practice, namely ensuring that “the disproportion between effort and effectiveness was at least retrospectively rectified.”73 It is also noteworthy that Marianne Tralau’s only monographic exhibition took place at the EIGEN + ART gallery in Leipzig in May and June 1989, i.e. in the GDR before the opening of the Berlin Wall.

At this point, EIGEN + ART had already gradually internationalized its exhibition program. As Lybke later put it, it was part of the gallery’s concept to include international artists: “Bringing other artists to Leipzig, thereby responding reflexively to this city, means dealing with the given conditions, engaging with them in Leipzig, working on site.”74 The first exhibition featuring artists living abroad was held in February 1988 and was dedicated to the work of five Georgian artists from Tbilisi.75 This was followed by a solo exhibition by the Polish artist Sbyzek Szumski, who lived in Gdańsk, in April, and in July 1988, the Icelandic artist Björg Örvar showed her works on paper.76 Even before Marianne Tralau, the first West Germans were the Munich-based artists Gerhard Petri and Siegfried Kaden, who showed installations and drawings in a joint exhibition in October 1988.77 It can be assumed that works were created specifically for the exhibitions—both for the specific occasion and, as is customary at EIGEN + Art, more or less on site. Lybke saw all of his Leipzig exhibitions as “not inventories from the studios, but rather a working with the spaces and the location of the gallery.”78 In addition to its fundamental claim to show “new works relating to the specific situation,” it was probably also a pragmatic decision to refrain from importing saleable works of art—not least in order to avoid jeopardizing the artists’ entry into the country through illegal imports.

By selecting artists from the Soviet republic of Georgia and the Eastern Bloc state of Poland, the gallery initially remained within the sphere of the “socialist brother countries,” i.e., those states that had signed the Warsaw Pact and with which the GDR maintained close political relations. Inviting an artist from Iceland, on the other hand, was a particular provocation from the GDR’s state-logical perspective: “Western contacts” were monitored, subject to state control, and could be banned. This applied to all contacts in the “non-socialist economic area,” i.e., all states outside the Warsaw Pact or the Council for Mutual Economic Assistance, but especially with the Federal Republic of Germany. German-German relations were under special observation, and people with intensive contacts posed an increased security risk for the GDR.

From today’s perspective, one incident in 1986 shows just how sensitive German-German relations were in the gallery’s environment, when the Stasi saw an exhibition featuring works by Karin Plessing (b. 1949) and Lutz Dammbeck (b. 1948) as a “convenient opportunity” to close the gallery.79 Both artists had applied for an exit visa, which was originally supposed to be granted shortly after the exhibition opened so that the departure of an artist who had moved abroad could be used as a pretext for closing the exhibition. However, concerns among secret service agents that the exhibition could be perceived as “defamation of socialist cultural policy” prevailed, and the exit visa was granted earlier than planned.80 The gallery remained true to its principle of requiring artists to be present and canceled the exhibition.81

As early as 1985, the Stasi had opened an investigation against Judy Lybke, thereby laying the structural groundwork for combating the activities of EIGEN + ART.82 The archive he had carefully built up could potentially have been used as evidence in proceedings relevant to administrative or criminal law. In principle, the provisions of the GDR Criminal Code on treason, subversive agitation, and anti-constitutional associations were available, although the Stasi’s investigations in the field of alternative culture usually ended with the gallery activities being deemed not relevant under criminal law.83 But even when criminal prosecution was unlikely to succeed, the state resorted to aggressive methods of liquidation or more subtle forms of so-called “Zersetzung” (destruction) in order to target private galleries through the Stasi.84 This also included administrative offences and offences punishable by fines relating to regulations governing commercial activities, the organization of events (especially those involving persons residing abroad), socialist coexistence, or the production of printed and reproduced materials.85

Despite controls and the constant presence of undercover Stasi agents in the gallery, EIGEN + ART was able to operate without major disruption.86 After the initial strategy of legal action proved fruitless, in 1989 the decision was made to “officialize” the private gallery, i.e., to transfer it to the state cultural and exhibition system.87 Despite not having a university degree or party membership, Judy Lybke was accepted as a candidate for the VBK in November 1988. Using EIGEN + ART as an example, a cultural policy pilot project was even planned, with the gallery to be developed into a figurehead for a cultural change of course, but this became obsolete with German reunification.88 The fact that EIGEN + ART was able to operate relatively unhindered and increasingly professionalize its gallery activities compared to other private galleries in the GDR is explained today not only by the cultural policy changes in the late phase of the GDR, but also in particular by the gallery’s high profile both at home and abroad, especially in the Federal Republic of Germany.89

By the end of 1989, EIGEN + ART had become a fully public gallery, with exhibitions attracting up to 700 visitors.90 On September 9, 1987, the gallery received its first mention in a Leipzig daily newspaper; shortly thereafter, it appeared in the exhibition calendar of the monthly magazine Bildende Kunst, published by the VBK—which, according to contemporaries, was tantamount to “official recognition.”91 In the years leading up to the opening of the Berlin Wall in 1989, there were at least five mentions in the West German press.92 The gallery’s professional communication and documentation—in conjunction with other infrastructural services ranging from renting to regularly programming and opening the gallery spaces to involving experts—gave the young gallery and its program weight and visibility; this was also reflected in its growing network, which became increasingly Western German. However, the gallery’s location in Leipzig, an international trade fair city, was undoubtedly also a contributing factor.

No other city in the GDR was more strongly influenced by trade fairs and, at least during the trade fair season, more international than Leipzig. The city was a central trading hub between the former Eastern and Western blocs, which meant that it always had to serve as a figurehead for the GDR and therefore triggered special activities on the part of both the state and the alternative and dissident scenes. It was no coincidence that the opposition groups that had been meeting in Leipzig’s Nikolaikirche for years held their first demonstration on September 4, 1989, during the Leipzig Autumn Fair, thus initiating the Monday demonstrations that were to have such far-reaching consequences for the opening of the Berlin Wall. Banners bearing slogans such as “For an open country with free people” and “Freedom of travel instead of mass flight” were torn from the hands of demonstrators by plainclothes Stasi officers, all in full view of the West German and international press reporting from the city during the Leipzig Autumn Fair. In addition to journalists, diplomats and all kinds of trade and business representatives traveled to Leipzig every year for the annual spring and autumn trade fairs, exploring not only the fair but also the city and its alternative art scene.

Photographic Documentation of the Visit of the Cultural Committee of the Federation of German Industries (BDI) to the Workshop-gallery EIGEN + ART in Leipzig Connewitz, 1989, 1 black and white photographs, original prints, photographer unknown. Courtesy of the Archive Galerie EIGEN + ART Leipzig/Berlin. Pictured are in front of the Workshop-gallery EIGEN + ART, among others, Bernhard Freiherr von Loeffelholz (far right), Jürgen Blankenburg (second from right), Michael Tacke (fourth from right), Arend Oetker (sixth from right), Brigitte Conzen (later Oetker, second from left), Klaus Werner (third from left), and Judy Lybke (fifth from left).

The gallery owed its most prominent and perhaps most significant visit before the opening of the Berlin Wall less to the fair than to the special commitment of art historian Klaus Werner, who was known beyond the borders of the GDR for his expertise in contemporary art. In July 1989, he visited the EIGEN + ART gallery with representatives of the Cultural Committee of the Federation of German Industries (Bundesverband der Deutschen Industrie, or BDI).93 Photos of the event show Judy Lybke proudly presenting his visitors with prints and other works on paper by his artists and the gallery. Among the visitors were influential industry giants such as Bernhard Freiherr von Loeffelholz (1934–2024), who was a banker and later chairman of various art foundations, in particular the Jürgen Ponto Foundation for the Promotion of Young Artists. Also present was entrepreneur and art collector Arend Oetker (b. 1939), who had visited the Leipzig trade fair with his companies for many years, developed a special relationship with the city, and received the Saxon Order of Merit in 2022 for his philanthropic commitment.94 This visit had far-reaching consequences for the city of Leipzig, because during their stay, the representatives of the cultural circle were inspired to support the establishment of a gallery for contemporary art, and just one day after the opening of the Berlin Wall, a call for potential donors was issued.95 The Gallery for Contemporary Art (Galerie für zeitgenössische Kunst, or GfzK) was founded in 1998 under the direction of Klaus Werner and with great commitment from Arend Oetker, and continues to provide curatorial inspiration far beyond the borders of Leipzig to this day.

It was Arend Oetker who granted Judy Lybke a guarantee loan to enable EIGEN + ART to participate in the West German art fair “Art Frankfurt” in March 1990, even before reunification.96 At the end of 1990, the gallery participated in Germany’s most important art fair, Art Cologne, and in 1991 it took part in a fair in Tokyo and in Art Basel; ever since, the gallery has been represented almost without interruption at Art Basel, which has developed into the most important art fair in the Western world. Even before its stay in New York, the gallery maintained short-term branches in Paris and Berlin in 1991, before moving into permanent premises in Berlin’s Mitte district in 1992.97 In Leipzig, EIGEN + ART found its current location in 2005 on the grounds of the Baumwollspinnerei, a former cotton mill, where some of its artists also have their studios, most notably the GDR-born artist Neo Rauch (b. 1960). Together with younger painters such as Tim Eitel (b. 1971), Christoph Ruckhäberle (b. 1972), and Matthias Weischer (b. 1973), who were born in West Germany but trained in Leipzig, this location is now known as the “New Leipzig School” on the art market. The term refers to the painters of the so-called “Leipzig School,” such as Bernhard Heisig, Wolfgang Mattheuer, and Werner Tübke, who were courted in the GDR and also became known in the West through their participation in documenta 6 in Kassel in 1977. Their students, in particular Sighard Gille and Arno Rink, were often teachers at the HGB of the “New Leipzig School.” This “school,” which is extremely successful in today’s art market, particularly with Neo Rauch, shapes the current image of the EIGEN + ART gallery. But artists such as Heisig, Mattheuer, and Tübke, or Gille and Rink, who were courted with state prizes and offices under socialism, could not be further removed from the early days of Lybke’s gallery in the alternative cultural scene of the GDR. The artists from the GDR who were active in New York are much more in line with this tradition, and Jörg Herold, Uwe Kowski, Maix Mayer, Carsten, and Olaf Nicolai are still represented by EIGEN + ART today.

Was It Worth It?

When Lybke opened his four-month New York branch in March 1993, he had already worked with all of the participating artists and exhibited their work on several occasions. Jörg Herold and Uwe Kowski had already exhibited in the attic apartment in Leipzig; Rainer Görss, Kaeseberg, Carsten, and Olaf Nicolai showed their art for the first time in the gallery in 1988, Maix Mayer in 1990, Annelies Štrba in 1991, and Cornelia Parker in 1992. In both Leipzig and later in New York, Lybke offered an infrastructure that not only enabled the display of art but also created a framework for discourse and for the circulation of information surrounding it. The relatively high-quality catalog, with a print run of 1,000 copies, served as documentation, as was typical for EIGEN + ART, but did not follow the artistic books that had been particularly influential for the gallery and the artists before 1989. With access to offset printing machines after the opening of the Berlin Wall, they were able for the first time to create such high-circulation, machine-produced publications, and the gallery made extensive use of them, seeing them as a means of communication to engage in dialogue with other artists, curators, journalists, and collectors.

Lybke’s credo for Leipzig—not to show inventory from the studios, but to work with the gallery’s spaces and location—was also realized in New York by the participating artists. This approach had allowed the gallery to expand its program in the 1980s with international guests and now enabled the artists to establish direct international references in their works. However, pragmatism certainly played a role in both situations in order to circumvent import and export regulations and keep transport costs to a minimum. The artists traveled to New York for the exhibition series and were present for the entire duration of their own exhibition (albeit not during opening hours, at least in the city). It is reminiscent of the Leipzig years that in New York, too, effort and costs were kept to a minimum and everyone shared the financial risk by organizing their own travel and accommodation. In any case, no one had expected any sales in New York, as all the interviewed participants recently confirmed again to the authors.

When asked shortly after returning from New York whether it had been worthwhile, gallery directors Elke Hannemann and Kerstin Wahala told the local newspaper Hallesches Tageblatt: “If you mean financially, you’ll have to ask us in a few months. There’s a reciprocal effect. That’s how Judy planned it. We were more successful there than we expected.” Apart from the sales, Kerstin Wahala continues in her response, “New York impressed everyone. It put things into perspective and made us more critical of our own positions. Artists and gallery owners alike.”98 Everyone involved in the “We are in New York” project felt the same way as the artist Uwe Kowski, who remarked: “Here he was a stranger among strangers, and he liked it. […] This crazy city, and what he experienced there got under his skin.”99 The social and economic differences, which were hardly noticeable in the GDR but are starkly evident in New York, also left their mark.100

The parallels between EIGEN + ART’s activities in Leipzig and New York are clear. One could conclude that the gallery in New York simply applied tried-and-tested strategies, worked with artists it knew well, and took few risks. Especially in comparison to the Leipzig period—when simply exhibiting art, bringing artists and visitors together, or printing catalogs was enough to attract the attention of the Stasi and trigger legal and secret service harassment—the New York venture seems almost harmless, despite the higher crime rate in Alphabet City. But opening a temporary gallery in the Western center of the art market, especially during an economic crisis, carried a completely different risk: that of being ignored. In the German context, the gallery in Leipzig was needed as an alternative infrastructure because there was no opportunity for this type of art within the state structures, and the public welcomed the gallery with open arms; New York did not need another gallery and was not waiting for EIGEN + ART or other German galleries.

Under the headline “The Art Market,” the New York Times reported only on David Zwirner, the Cologne art dealer’s son, and his intention to open a contemporary art gallery in the city.101 The branch of the East German gallery EIGEN + ART was announced only in a special journal for collectors of prints, The Print Collectors Newsletter, but at least did so in relative detail.102 The fact that EIGEN + ART nevertheless received a mention in the New York Times during its stay in New York, not as an art market report but in a text by art critic Roberta Smith, was thanks to a coincidence. What the Leipzig guests had not anticipated was that their stay would coincide with an unusually high concentration of exhibitions by German artists—a concentration that New York had probably never experienced in a single year before.

In the spring of 1993, The Museum of Modern Art alone presented three monographic exhibitions on Joseph Beuys, Max Ernst, and John Heartfield; in addition, the SoHo branch of the Guggenheim Museum presented a major exhibition entitled “Photography and Contemporary German Art: 1960 to the Present.” DIA’s Chelsea location with a Katharina Fritsch installation, the New York Kunsthalle with works by Felix Droese, and the P.S. 1 Museum together with the New York Goethe Institute with “Parallax View: New York-Cologne.” In the Critic’s Notebook section under the headline “German Art Still Breathes the Air of Idea,” Smith praised the exhibitions of German art, some in great detail, and reflected on larger questions—such as their historically lower reception compared to French art. The text also discussed, albeit more briefly, five commercial exhibitions by Hirschl & Adler Modern, Margarete Roeder Gallery, Marian Goodman Gallery, Nordanstad Gallery, and EIGEN + ART, with the Leipzig gallery receiving the most coverage:

Eigen + Art, which began 10 years ago as an underground gallery in Leipzig, East Germany, has set up shop for a few months in SoHo to present group exhibitions of artists from Germany’s eastern half. Their current show of Expressionistic paintings and woodblock prints by Carsten Nicolai, a large multi-part, vaguely Minimalist plaster sculpture by Jorg Herold and an installation involving photographs of New York skyscrapers by Maix Mayer, is informative, if not exactly thrilling.103

Although this brief review did not reflect the almost euphoric tone of the extensive coverage in the German media and criticized the art program as “informative,” this mention was an enormous success for the EIGEN + ART gallery; this made it sound as if the gallery naturally belonged among the SoHo galleries, and as if the artists mentioned individually were household names on the emergent New York art scene. The young gallery and its artists, exhibiting in New York for the first time, were competing at the center of the art world, and they were also being taken seriously and receiving criticism from the New York Times, one of the oldest and most influential newspapers in the US.

Exposing oneself to the New York art scene took courage, but as Lybke said in one of his interviews, opening a gallery in Leipzig also required grit. EIGEN + ART was able to draw on its experience and strategies from Leipzig for this SoHo venture, convincing its artists to participate and offering them an infrastructure in New York for four months to exchange ideas about the art on display—and certainly to argue about it, preferably with the artists themselves, as Karim Saab recalled from Leipzig. The early internationalization efforts and “Western contacts” also bore fruit in New York. The commitment of American artist Christine Hill to the New York branch during its run should not be underestimated. As an insider of the New York art scene, she provided important inspiration and stimuli in terms of content, established contacts, and facilitated exchange. Ultimately, apart from Cornelia Parker, who was present for a shorter period, Hill was also the only native speaker of English among the East German artists and staff, whose first foreign language in school was still Russian. But the contact with Arend Oetker may also have been significant. It was probably he who brought EIGEN + ART in New York to the attention of Timotheus R. Pohl (1939–2024), CEO of Daimler-Benz Systems in the US, because they were both involved in supporting the Busch-Reisinger Museum at Harvard University in Cambridge, Massachusetts, which focuses on German art. Timotheus R. Pohl visited the New York gallery several times, bringing along art-loving visitors from the Busch-Reisinger circle of supporters and, in turn, giving the artists at EIGEN + ART access to the New York art scene.

“Was the trip to New York worth it?” Looking back, gallery owner Gerd Harry Lybke answered this question on January 9, 2025: “When Berlin became the hotspot of the international art scene in the mid-1990s, American journalists, curators, art lovers, and collectors remembered EIGEN + ART in New York. They knew our name and looked up our address. Then they came to us in the Auguststraße location and asked where to find a good hotel and restaurant in Berlin, what sights they absolutely had to see, which club was currently trendy, and whether we knew so-and-so. We were happy to help. And then a few years later, they bought from us.”104

Photographic documentation of the exhibition series We are in New York, March 11 to June 26, 1993, color photograph, original print, photographer unknown, AGEA, call number: A-1993-1280. Courtesy of the Archive Galerie EIGEN + ART Leipzig/Berlin. Pictured: Judy Lybke on the phone at the reception desk of the exhibition space at 578 Broadway, New York.

Bibliography

Primary Sources

Archive of the Gallery EIGEN + ART / Archiv Galerie EIGEN + ART (AGEA):

Series A. Exhibitions / Ausstellungen

Series B. Documents on the Work of the Gallery EIGEN + ART / Dokumente zur Arbeit der Galerie EIGEN + ART

Series C. Documents on the Life of Gerd Harry Lybke / Dokumente zum Lebensweg Gerd Harry Lybke

Series H. Edition EIGEN + ART / Edition EIGEN + ART

Secondary Sources

Bayer AG Leverkusen. EIGEN + ART - eine Galerie aus Leipzig, 3 vol., edited by Frank Eckart, Uta Grundmann, and Gerd Harry Lybke. 1991.

Belkin, Lisa. “The Gentrification of the East Village“ The New York Times, September 2, 1984. https://nyti.ms/455wUqV.

Bundesverband der Deutschen Industrie. “BDI-Bericht 1988-1990”, December 3, 1990.

Cliff, Claudia. “Willkommen zurück. [Der Künstler Uwe Kowski in New York]“, unpublished manuscript, Private Archive of Frank Eckart, Berlin, September 2021.

Cohen-Solal, Annie. Leo and His Circle: The Life of Leo Castelli. Alfred A. Knopf, 2010.

Eckart, Frank. “‘Was Leipzig druckt sey prächtig schön’ oder Wie kam die Malerei in diese Stadt?“ Leipziger Blätter, no. 65 (2014): 78-80.

Carsten Nicolai. Interview by Frank Eckart. February 4, 2024.

Christine Hill. Interview by Frank Eckart. January 27, 2025.

Judy Lybke. Interview by Frank Eckart. January 9, 2025.

Judy Lybke. Interview by Frank Eckart. February 5, 2025.

Kerstin Wahala. Interview by Frank Eckart. January 17, 2025.

Olaf Nicolai. Interview by Frank Eckart. December 16, 2024.

Olaf Nicolai. Interview by Frank Eckart. January 26, 2025.

Eckart, Frank. “Nie überwundener Mangel an Farben… Über ein Kapitel der Kulturentwicklung in der DDR der achtziger Jahre” In Eigenart und Eigensinn. Alternative Kulturszenen in der DDR 1980-1990, edited by Forschungsstelle Osteuropa. Edition Temmen, 1993.

Eckart, Frank. “Zwischen Verweigerung und Etablierung: Bd. 1: Eigenständige Räume und Produktionen der Kulturentwicklung in der DDR der achtziger Jahre der bildenden Kunst in der DDR der achtziger Jahre und die Entwicklung der Leipziger Werkstattgalerie Eigen + Art (1985 bis 1989)“ Diss., Universität Bremen, 1995.

“Ein Bild des Jammers“ DER SPIEGEL, no. 52, December 26, 1993. https://www.spiegel.de/wirtschaft/ein-bild-des-jammers-a-4bf13404-0002-0001-0000-000013693422?context=issue.

Fiedler, Yvonne. Kunst im Korridor: private Galerien in der DDR zwischen Autonomie und Illegalität. Ch. Links Verlag, 2013.

Galerie EIGEN + ART, ed. We are in New York: Rainer Görss / Jörg Herold / KAESEBERG / Maix Mayer / Carsten Nicolai / Cornelia Parker / Annelies Štrba. Edition EIGEN + ART, 1993.

Galerie EIGEN + ART. “Exhibitions Archive“. https://eigen-art.com/ausstellungen/archiv/.

Gillen, Eckhart. Das Kunstkombinat DDR: Zäsuren einer gescheiterten Kunstpolitik. DuMont, 2005.

Gillen, Eckhart. Feindliche Brüder? Der Kalte Krieg und die deutsche Kunst 1945 - 1990. Nicolai, 2009.

Grundmann, Uta. „Die Galerie Eigen + Art“, September 6, 2012. https://www.bpb.de/themen/deutsche-teilung/autonome-kunst-in-der-ddr/55832/die-galerie-eigen-art/.

Grundmann, Uta, Klaus Michael, and Susanna Seufert. “Die Theatralik grenzenlosen Selbstverständnisses – eine neue ‚Generation‘ tritt auf“. In Die Einübung der Aussenspur: Die andere Kultur in Leipzig 1971-1990, edited by Uta Grundmann, Klaus Michael, und Susanna Seufert. Thom Verlag, 1996.

Grundmann, Uta, Klaus Michael, and Susanna Seufert. “Lebensart im Niemandsland - ein Milieu sucht Unterkunft“. In Die Einübung der Aussenspur: die andere Kultur in Leipzig 1971-1990, edited by Uta Grundmann, Klaus Michael, und Susanna Seufert. Thom Verlag, 1996.

Herold, Thea. “Risiko – maßgeschneidert: Von Leipzig nach New York: Die Galerie EIGEN + ART“ DIE ZEIT, March 26, 1993. https://www.zeit.de/1993/13/risiko-massgeschneidert.

“Hoffmann, Christiane, and Christoph Tannert. Im Gespräch“. In Ortszeit. 1992.

Knabe, Hubertus. “Nachrichten aus einer anderen DDR. Inoffizielle politische Publizistik in Ostdeutschland in den achtziger Jahren“ APuZ (Aus Politik und Zeitgeschichte), no. 36 (August 28, 1998). https://www.bpb.de/shop/zeitschriften/apuz/archiv/538611/nachrichten-aus-einer-anderen-ddr-inoffizielle-politische-publizistik-in-ostdeutschland-in-den-achtziger-jahren/.

Kuhn, Nicola. “Ein Leipziger in New York: Der Galerist Gerd Harry Lybke und seine Künstler auf Firmenausflug“ Der Tagesspiegel, April 25, 1993.

Lange, Herbert. EIGEN + ART in der DDR und die Entwicklung der Galerie von ihren Anfängen bis zur Gegenwart im Spiegel der Presse. Magisterarbeit, Universität Leipzig, Institut für Kunstgeschichte, 2010.

Lindner, Konrad. “‘Ich habe mich für Leipzig entschieden‘“. https://www.leipzig-lese.de/persoenlichkeiten/o/oetker-dr-arend/ich-habe-mich-fuer-leipzig-entschieden/.

Lybke, Judy to Frank Eckart, E-Mail from March 21, 2025.

Meier, André. “Die Werkstatt-Galerie Eigen + Art“. In Kunst in der DDR, edited by Eckhart Gillen und Rainer Haarmann. Kiepenheuer & Witsch, 1990, 415-417.

Metz, Katharina and Ingrid Mössinger, ed. Künstlerplakate: Artists‘ Posters from East Germany, 1967-1990. Kerber Verlag, 2009.

Michael, Klaus. “Die EIGEN + ART im Fadenkreuz“. In Die Einübung der Aussenspur: Die andere Kultur in Leipzig 1971-1990, edited by Uta Grundmann, Klaus Michael, und Susanna Seufert. Thom Verlag, 1996.

Michael, Klaus. “Alternativkultur und Staatssicherheit 1976–1989“, in Materialien der Enquete-Kommission “Überwindung der Folgen der SED-Diktatur im Prozeß der Deutschen Einheit“, vol. 3,3, edited by Deutscher Bundestag. Suhrkamp Verlag, 1999, 1636-1675

Michael, Meinhard. “‘Wir dürfen den Draht nicht verlieren‘. Im Gespräch mit den Galerieleiterinnen der EIGEN + ART in Leipzig und Berlin [Elke Hannemann und Kerstin Wahala]“ Hallesche Tageblatt, July 3/4, 1993.

“New Prosperity Brings Discord to the East Village“ The New York Times, December 19, 1983. https://nyti.ms/3UKKdqB.

“New York – New York: ‘Big Apple” fest in deutscher Künstlerhand“ B.Z., March 31, 1993.

“NEWS OF THE PRINT WORLD: People & Places“ The Print Collectors Newsletter 24, no. 1 (March-April 1993): 12-18.

OECD. OECD Economic Surveys: Germany 1993. OECD Publishing, 1993. https://doi.org/10.1787/eco_surveys-deu-1993-en.

OECD. OECD Economic Surveys: United States 1993. OECD Publishing, 1993. https://doi.org/10.1787/eco_surveys-usa-1993-en.

Offner, Hannelore. “Überwachung, Kontrolle, Manipulation“ in Eingegrenzt – Ausgegrenzt: Bildende Kunst und Parteiherrschaft in der DDR 1961-1989, edited by Hannelore Offner and Klaus Schroeder. Akademie Verlag, 2000, 165-309.

Offner, Hannelore and Klaus Schroeder, ed. Eingegrenzt – Ausgegrenzt: Bildende Kunst und Parteiherrschaft in der DDR 1961-1989. Akademie Verlag, 2000.

Pätzke, Hartmut. “Von ‚Auftragskunst‘ bis ‚Zentrum für Kunstausstellungen‘: Lexikon zur Kunst und Kunstpolitik in der DDR“. In Kunst in der DDR. Eine Retrospektive der Nationalgalerie, edited by Eugen Blume und Roland März. G & H Verlag, 2003.

Reda, Valerie. “Die KAOS-Galerie - Eine freie und unabhängige Kunstinitiative“. In Saalzeitung. ZADIK, 2018.