Tytuł

Etched into Memory Regina Lichter-Liron’s Holocaust Album 1939-1945*

https://doi.org/10.48285/ASPWAW.29564158.MCE.2023.9.8

https://miejsce.asp.waw.pl/etched-into-memory-regina-lichter-lirons-holocaust-album-1939-1945/

Abstrakt

Only ten months after her liberation from Neustadt-Glewe on the first of May 1945, a young Jewish Polish survivor named Regina Lichter created a graphic album of her experiences during the Holocaust while she was living as a displaced person in Italy. Entitled only 1939-1945, her album is an exemplary testimonial object, comprised of words and images, that recounts the ‘double jeopardy’ women faced during the Holocaust. It draws a portrait of her emotional ties to family, the hard labour she was subjected to, the things she witnessed, and the deprivation and dehumanization she endured. Above all, it is a chronicle of unbearable loss. This essay offers a close reading of her album and its constituent parts−visual and textual, artistic and literary−attending to the object’s materiality and the particular print technology she chose for her testimonial poetics: etching. I situate Lichter’s “unbelated” visual testimony within the largely hidden history of the She’erit Hapleitah’s artistic activities in Italy in the early postwar period. As one of many overlooked postwar ‘imagetexts of witness’ created by artists hovering on the edges of art history, her album allows us to ‘difference’ the canon of Holocaust art.

DOI

‘For those of us who live […]

at once before and after

seeking a now that can breed

futuresFor those of us

who were imprinted with fear […]

it is better to speak

remembering

we were never meant to survive.’Audre Lorde, ‘A Litany for Survival’1

In 1947, Filip Friedman, the head of the Central Jewish Historical Commission in Poland, observed that Holocaust survivors were driven by ‘an irresistible inner urge [to] grab a pen to write’ and that these accounts were not ‘isolated cases of a form of graphomania’, but rather ‘a mighty social phenomenon’.2 Artists were a part of this collective impulse, but their ‘graphomania’ required additional tools – pencils, paints, and styli. And they were not only compelled to write their stories but to draw and paint and print them, and later annotate them with captions and textual commentary. A young Jewish Polish survivor named Regina Lichter created one such graphic narrative only ten months after her liberation from the Neustadt-Glewe concentration camp, while she was living as a displaced person in Italy. Entitled 1939-1945, her album is an exemplary ‘testimonial object’, comprised of words and images (Figure 1).3 It draws a portrait of her emotional ties to family, the hard labour she was subjected to, the things she witnessed, and the deprivation and dehumanization she endured. Above all, it is a chronicle of unbearable loss.

Figure 1. Regina Lichter-Liron, cover of Album 1939-1945, Florence, 1946. Collection of the Yad Vashem Art Museum, Jerusalem. Donated by Yad Itzhak Ben Zvi

Although testimony is at the centre of academic engagement with the Holocaust, extralinguistic sources that go ‘beyond words’ are rarely considered trustworthy, as Leora Auslander has argued.4 When visual testimonies are attended to, they are often used as documentation or mere illustration, often divorced from the social conditions of their production, circulation, and consumption: the ‘when’, ‘where’, ‘why’ and ‘how’ they were made. Lichter’s ‘un-belated testimony’5 nuances accepted narratives of the ‘return to life’. It highlights the largely hidden history of the She’erit Hapleitah’s (Surviving Remnant’s) artistic activities in the early postwar period and asks us to expand the very definition of what constitutes testimony.

This essay is part of a larger project to recover the work of several female Holocaust survivors who took to graphic narratives as a form of testimonial storytelling-picturemaking. Tweaking the title of Michel Foucault’s Lives of Infamous Men, I am interested in the ‘lives of unfamous women’: those whose ‘brief lives, encountered by chance in books and documents’, offer a sign of ‘the action, in disorder, noise, and pain, of power on lives and the discourse that comes of it’, as Foucault wrote.6 Lichter’s 1939-1945 has never been exhibited nor reproduced in full.7 Yet, it belongs to an untapped mine of early postwar artistic initiatives about women, by women hovering on the edges of art history who sought to record their traumatic experiences. These overlooked ‘imagetexts of witness’8 allow us to ‘difference’ the canon of Holocaust art – a canon that is increasingly consolidated and consecrated through reproduction, exhibition and scholarship.9 They call for a self-critical historiography that attends to the marginalised or silenced testimonies of women survivors.

1939-1945

I discovered 1939-1945 in the archives of the Art Museum at Yad Vashem in Jerusalem, where it is inventoried as ‘An album of etchings about the Holocaust (10 in number) made by רחל (Rachel) Lichter in 1946’.10 It had been donated in 1994 by the director of another archive in Jerusalem, Yad Itzhak Ben Zvi.11 But the ‘artist’s file’ at Yad Vashem was woefully incomplete, with little to no information on when Lichter had been born, her whereabouts between 1939 and 1945, or even when she had died. She does not figure in any of the now canonical books on ‘Holocaust art’.12 In fact, the only reference I found to her in the secondary literature was in an article by Mor Presiado on ‘Sexual Violence during the Holocaust in Women’s Art’; however, it focused on just one print.13

Because I encountered the album prior to knowing any biographical details about her life, I was forced to spend time with the object, to focus on how it had been made. In other words, I had to infer details about her Holocaust experiences based on what I saw and read, by ‘reading the picture’ instead of ‘seeing the artist’.14 By exploring the work first through ‘slow looking’, rather than drawing on anecdotal support that corroborates contextual or biographical information, I noticed things I would have otherwise overlooked. As a practice of immersive attention, ‘slow looking’ has become fashionable over the last decade amongst scholars.15

But as those of us who study the art and artifacts of this period know all too well, ‘slow looking’ is not a supplemental strategy; most of the time, it’s all we have.

The album itself is a beautiful object, clearly hand-crafted and lovingly assembled. Bound by a black and white braided string threaded through two hole-punches, its size and weight and hardback, linen-cloth cover gives it the look and feel of a family album. Inside, the artist had alternated thick sheets of black and white heavy-weight paper: small, typewritten texts had been glued onto the black ones and ten prints – etchings to be precise – were set into cream-coloured passe-partout frames. The album’s method of construction indicated an extraordinary investment of time: the time to make the prints, beginning with preparatory drawings through all of the stages of the lengthy etching process, from covering the metal plate with a ground of acid-resistant varnish or wax, carving into it with the etching needle for line, tone and texture, proofing and toning the plate, bathing it in acid (copper sulphate or ferric and nitric acid solutions) before running it through a press onto moistened paper. And it then took time to assemble the album: composing the text, typing it by hand, correcting the numerous typos, and finally collating the typewritten sheets onto the support and mounting the prints into their card-stock frames. The quality of the album, and its relatively expensive materials, also bespoke access to resources – a printing press for one – suggesting that the artist was working within a collective workshop or art school equipped with printmaking tools and technologies.

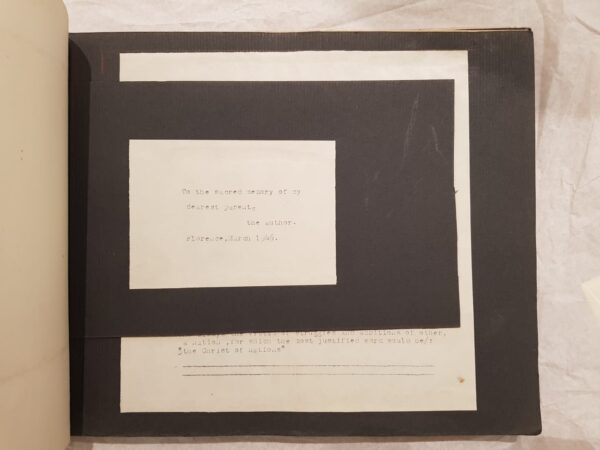

Each print was signed on the lower margins of the plate, with the artist’s initials ‘rl’ etched into the plate in cursive. The proper name of the artist, however, was nowhere given: not on the cover – which features, instead of a title, only the dates 1939-1945 framing a skull superimposed askew over a swastika, in the lower right-hand corner – nor in the dedication inscribed on the opening page. Although the hand of the artist may be discerned in the cover’s hand-drawn inscription with felt marker, the artist’s name is ‘drawn out’. The same applies to the dedication, which is inserted on the first page of the album, on a smaller, hand cut sheet, and reads only ‘To the Sacred Memory of My Dearest Parents. The author. Florence, March 1946’ (Figure 2).

Who was ‘rl’? Why did ‘the author’ not sign the album with her proper name? What secrets does this album disclose about Lichter’s experiences during the Holocaust? And what does it reveal about her ‘return to life’ after the war? 1939-1945 poses complex methodological challenges to even the most dedicated researcher; its images and texts do not conform to expectation, nor do they offer a straightforward reading. As Patricia Yaeger has noted, testimonies do not always ‘behave’.16 ‘How badly they behave’ has implications for their legibility – and, by proxy, for their visibility in scholarship. Lichter’s album is a difficult object, not least because its author was, at least initially, a mystery. How do we approach artworks and objects in the archive untethered to an authorial entity? In the absence of a name or complete biography, what kinds of historical insights can we glean from its physical composition and materiality? And how do we come to grips with incomplete testimonies, those that refuse to coalesce into coherent narratives?

To withhold her proper name is a remarkable choice – particularly for a young, budding artist in training. Indeed, Lichter could have ‘made her name’ by marking the work, signing it, and bestowing upon it an authorial identity – what Foucault called the ‘author-function’ – that would have allowed her work to enter art history. Instead, she largely ‘draws herself out’.17 (Her choice of type also conveys a sense of detachment.) In so doing, she becomes ‘a placeholder for all the others’; ‘Anonymity enables her to stand in for all the others. A minor figure yields to the chorus’.18 Lichter insisted as much in 1978 when she noted that, ‘I didn’t want only to recall my sufferings, and maybe it is because of that that there are no faces, because I did not want to show only what I had suffered, but what all of us had suffered’.19

Contra Annette Wieviorka, who argued that ‘In the postwar period, the meaning of testimony remained largely personal’, Lichter’s work was deliberately addressed to others.20 Two things stand out: the mode of transcription – type – and the language of inscription – English. A personal album made for the author/artist would not have been signed ‘the author’. Moreover, it would have been written in her mother tongue, Polish. That Lichter chose type indicates a concern with legibility. That she chose English, rather than her native Polish or Italian, the language of her new place of residence, suggests Lichter aimed to address an international audience, and the many misspelled words, awkward idioms, and hand-made corrections betray the barriers preventing her from doing so. From these clues, we can infer that the work was crafted as a public text intended for mass consumption through reproduction (why else use print and type?).

Beginning in 1939, her testimony moves chronologically, adhering to a rough timeline punctuated by freeze-frames of particularly notable traumatic memories. Her storytelling assumes a staccato rhythm, lurching from one scene to the next, with few connectors weaving them into a continuous narrative. This is a narrative wherein, as Victor Klemperer wrote in 1944, ‘the facts hardly hold together, dates not at all’.21 Moreover, her lengthy descriptions are not captions per se, as they do not always explicate the image (or ‘duplicate the image’, as Barthes argued).22

What is strikingly missing are historical and contextual identifiers. Although she uses the first person in her narration (my mother, my father, my brother, I, our), there are few dates, names and places given. She describes moving into a ‘ghetto on the Vistula’ but does not name it (the Kraków ghetto) or the series of camps she passed through (Plaszów, for one). She notes that her father was deported to Bełżec but offers nothing concrete about the fate of her mother and brother; as she writes in the text accompanying panel 1: ‘I do not even know to tell how she died (killed)’. Although lacking facts, Lichter’s texts nonetheless reveal much about her emotional state. The stuttered repetition of syllables, words and even full phrases, her many grammatical ‘errors’ and orthographic ‘mistakes’ (incorrect spelling, hyphenation, capitalization and punctuation) convey raw emotion and urgency. Therefore, the original texts are transcribed below as is, without correction.23

The album opens with two full pages of typed text articulating her mission statement:

‘These few pictures shown here, try to give a slight idea of the martyrdom and tragedy of the jewish people who were the victims of a crime unknown in the whole human history and committed by a nation which called herself cultured in Europe in the middle of the XX. century’.

Referring to her plight as ‘the tragedy of those poor survivers, the rests of broken families, who remained lonely standing on the heroic grave of the half of the nation’, she addresses her audience directly, alerting us to what we will not find:

‘I shall not give report of all the restrictions, I shall not describe the robbery, thieving, in the way of orders and beside them, I shall not picture the shameful deeds against old people, mocking, hitting and beating to deathall people who had the 3’luck3’ to be born Jews’.

She, thus, underlines that her refusal to ‘describe’ and ‘picture’ all she witnessed was not a failure of memory but a deliberate decision, a ‘gesture of refusal’.24

Panel 1 (Figure 3): The first panels capture the Nazis’ invasion of private, domestic spaces in the Kraków ghetto. Here, she depicts the heart wrenching moment her father was arrested and forcibly deported by soldiers. Set on the threshold of the house, Lichter depicts herself and her brother wailing on the bed and her mother desperately clutching her husband’s hand as he is taken away. Lichter’s text and image exudes raw emotion:

‘The first victim was my father, such a cultured person, so mild and good, that for us it was such a terrible thing, that I have not cried so much, as never before and never after […] And what I was the most afraid of that came. I could stand everything, the expelling of me, but dearest father, who always sacrificed his life for us […] he was suddenly picked up by an unexpected, additional troop of S.S. Parting he always was thinking of others and not of himself. ‘Take care of mother’ were his last words. My mother crying, my brother beside her and I would go with my father. I could not bear the idea, they will hurt him, the beasts. This time we were not aware, what was awaiting him, we still expected a letter – a letter from Belsec. The tragedy of one family was the tragedy of thousands of them’.

Panel 2 (Figure 4): In the second panel, Lichter lies in bed, in a room that doubles as a living room and opens onto the street, with her arms upraised:

‘Few minutes after parting of my father, with the cry ‘What I have seen’ rushed in my brother, pale and exhausted and fell in my arms. He pointed to the window. There was lyingon the ground an old man, his hat and stick behind him. It was the first victim in our ghetto, shot by the S.S., because he could not follow the others as quickly as it pleased the S.S. This was the sign of general shooting, and hundreds and thousands followed this firdt [first]’.

After this panel, Lichter draws herself out of the story, a self-effacement that allows her to move beyond the personal towards the communal.

Panel 3 (Figure 5): Panel three depicts the liquidation of the Kraków ghetto. From the close-up intimacy of the first two scenes, Lichter turns to an aerial, bird’s eye perspective, surveying the deportation from afar and above. In style, these panels appear ‘childish’ or amateur, with awkward spatial discrepancies and irregular perspectives.25 The composition is divided diagonally between the mass deportation on the right, and, on the left, an enlarged SS officer brutally grabbing a young girl by the hair as he pins her terrified mother to the ground with his boot:

‘Two times again happened this partly expelling of the ghetto. But still the ghetto, a shelter for the old, sick and children existed. And suddenly one beautiful Saturday in March 1943 came the order of liquidation at once of the ghetto. All the young, employed by Ger-Germans had to leave for the camp nearby, the other, as it was written in the order, will be taken in another camp. They were taken to the crematorium in Auschwitz. And what will happen to the old mothers and fathers, to the sich [sick] and to the children? The old we must sacrifice and the children will be brought to morrow into the camp, was told to the crying mothers. And if some mother would not believe this tale and could not part from her child, you see what happened to her. And the child was thrown to the other [officer].

Next day 2 thosands [thousand] corpses have been brought to the commen [common] grave in the camp’.

In March 1943, the bodies of victims who were killed during the liquidation of the ghetto – the women, old people, and children from Ghetto B who were classified as ‘unfit for work’ – were dumped into two large pits dug in the middle of Plaszów.

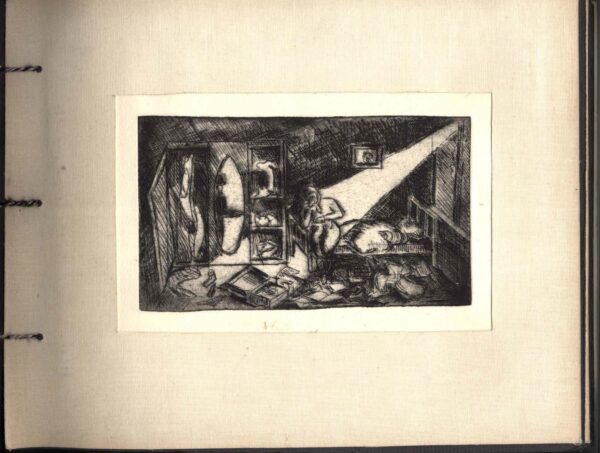

Panel 4 (Figure 6): The fourth etching depicts her ‘dearest mother’ […] crying helplessly’ in a ransacked room, with papers and clothes littering the ground:

‘And so the old, sick and children waited for their death […] And among them were you, my dearest mother. I see you sitting on your bed and crying helplessly. Your crying will follow me all my life. Alone in the whole dwelling, between broken stools and clothing left on the floor, with no living soul. Can you imagine this feeling – waiting, alone, helpless, unable to move, for the cruel death?’

Illuminated only by a shaft of light that slices through the darkness, her mother sits alone on the edge of a bed in the aftermath of a search, covering her face in one hand and her naked breasts with the other. To her right, the open doors of an armoire reveal, in the mirror’s reflection, the shadowy profile of a soldier pointing his gun at her.

Panel 5 (Figure 7): After the liquidation of the Kraków ghetto, Plaszów’s camp numbers swelled from 2,000 to 12,000. Living conditions in the camp were abysmal, with public shootings and hangings commonplace. The fifth panel depicts the forced labour she endured in the Liban quarry and the sadism of its commandant, Amon Goth, whom she refers to without naming him.

‘And the young went to live their poor and hard life on the cemetery. Because the camp was build [built] on the jewish cemetery and the stones of the statues were used were used for making the ways. It began with living in baracks, 200 and more in one, without washrooms and w.c., with no ways, mud everywhere and with hard work. You see women carrying heaving pieces of wood and heavy stones carried by by men. The commendant on his horse is watching the work and shooting, when not pleased, some of the workers. You see the S.S. watching and hitting the men. But there was also much harder work, there was building baracks with sweat and blood, there was loading cars, digging the earth and s.o. There could be an endless list of works and tortures the S.S. arranged’.

Composed as a vortex that spirals out counterclockwise from a pile of angular stones at the centre of the work, the print captures a ‘world of stone’, to borrow the title of Tadeusz Borowksi’s 1950 Kamienny świat. Here, in a kind of reverse Pygmalion myth, humans take on the characteristics of the inanimate stones they carry. Subjected to the work of hate, the victims become stone before stone-hearted perpetrators; they calcify, fossilise, mineralise, a petrification that registers their terror and dehumanisation.

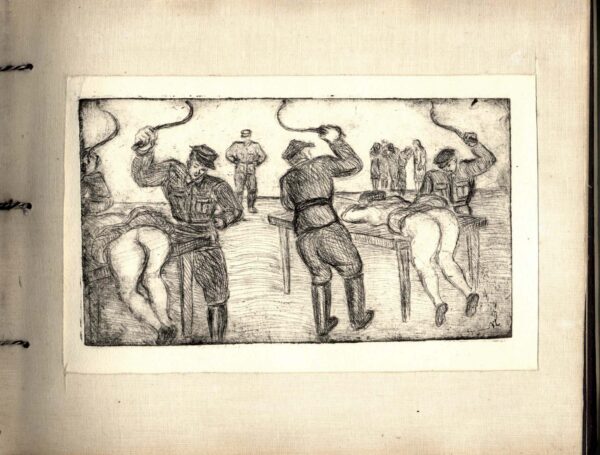

Panel 6 (Figure 8): The entire album foregrounds the precarity of being a Jewish woman in Nazi ghettos and camps, with close attention paid to communal (panels 6, 7, 8, 9, 10), marital (panel 1) and familial ties – and particularly those between daughters and mothers (panels 1, 2, 3 and 4). But Lichter is one of the few survivor women artists who testifies to the sexual violence women were subjected to. Panel 6 represents a graphic scene of female prisoners splayed out on torture tables, with their dresses rolled up, as SS men whip their exposed buttocks. She writes,

‘Sometimes the commendant wanted to show his power and to make a joyful spectacle for him. He ordered to gather all the people to the appelplace [Appelplatz]. We knew what it meant. Here he appeared with the doctor and his guard–a black guard. We prepared ourselves to death […] And the punishment began: he himself was going between the ranks and choosing victims. There were at first sad looking people, then all kinds of them. What punishment it was you see in the picture; fifty or more for one. And two of the black-guard for one. There was crying and praying but the strong instict [instinct] of live [life] heled to stand. The whole month after they felt sick and down-hearted, but they had to work’.

Unlike the ‘prurient voyeurism’ of David Olère’s early postwar work, which Carol Zemel described as a ‘full-on bacchanal’, ‘with the viewer as both moral witness and titillated spectator’,26 Lichter does not eroticise the victims. Although the bodies she renders are exposed, the artist withholds; she does not face the women. Rather than encouraging a prurient interest, the violations depicted present sexual violence as a tool ‘to show his [the commandant’s] power’: a sadistic public spectacle used to ensure control and demonstrate authority.

Panel 7 (Figure 9): In panel 7, Lichter covers the distribution of food to camp prisoners who file to receive their ‘poor [meager] soup’ in a desolate, inhospitable landscape:

‘I shall not feed you for nothing’ were his [the commandant’s] words […] And [the one] who had no friends in the kitchen, to get some more soup, could not manage other help’ could not stand it. And for this poor soup people stood in a row eager to get this little bit of some warm food. But until the last obtained, it was cold, and the first one, as you see, was hungry again’.

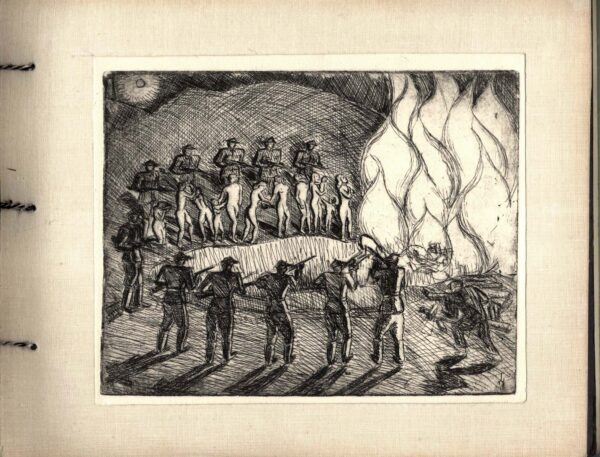

Panel 8 (Figure 10): The eighth panel is one of the darkest works in the album, both figuratively and literally, as it takes place at night and depicts a mass execution of Jewish victims from across a ravine. Lichter would have had to ‘work’ the surface painstakingly in order to achieve this density of black. She captures a line of naked Jews, who file across the edge of an open pit towards a wall of flames. Towards the summer of 1943, the Nazis began mass executions at a new site in Plaszów, ‘Hujowa Górka’ appellatively linked to Albert Hujar, one of the cruellest of the camp’s wardens. The practice of burning bodies on an open fire was used for the first time in December 1943. Lichter writes:

‘You see naked men, women and children. They had to jump into the hollow. Jum[p]ing they were shot and fell into the fire. The flame of this hellish fire is much stronger than the light of the moon, which is ashamed to gaze upon this execution’.

Illuminated by the fire, and in this way resembling Goya’s The Third of May, the victims are encircled by a firing squad of Nazi soldiers aiming their guns at them and directing them towards their deaths. Yet each of the figures is individuated; their body language and facial features betray a range of emotions, from panic to shock to grief. The figure closest to the pyre covers her breasts with her head held up in stoic resolve. Next to her is a mother clutching one child in her arms and another by hand; behind her is a group of three young women (‘graces’) clasping one another, then a mother and child, two women leaning on each other for support, a single woman and, at the rear of the procession, a woman, who has collapsed on her knees and shields her eyes. Lichter pre-emptively addresses the outside world directly:

‘You would say: Why didn’t you hide yourself among the nativve people. There were many Jews who tried to save themselves in that way but few of them survived. It was a terrible life in constant panic, for there was everywhere hunting for Jews, everywhere Gestapo agents. The most of these people were discovered, brought in prison and then found their death in the execution place in the camp’.

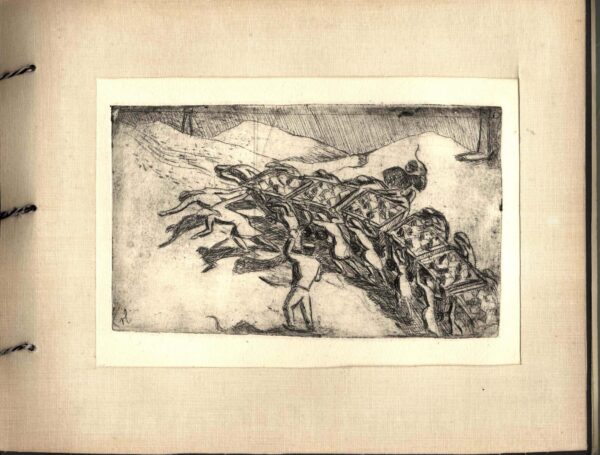

Panel 9 (Figure 11): The ninth panel features other ‘different kinds of torturing’ that women prisoners were subjected to. Set at night, against snow-covered hills, they flank a wagon laden with stones, buckling under the weight, as they are whipped.

‘There were different kinds of torturing. In the month’s of winter the commendant [commandant] got antipacy [antipathy?] to women. And so he arranged a new work for them: to pull the cars with stones at night, when snowing, when the way is frozen and when the cold wind is blowing. To cheer [him] up there were two men with their whpes [whips]. And sometimes the commendant himself would come, often drunken, and cheer up [enjoy himself] with his pistole’.

It is not only the ground and weather that is ‘frozen’, but the women, who are only ‘moved’ by the ‘sight of the commandant’. Surveyed from above, by watchtowers on the horizon, and beaten on both sides by Nazi officers, the faceless stick figures are stretched diagonally, like elastic, as they strain under the exertion.

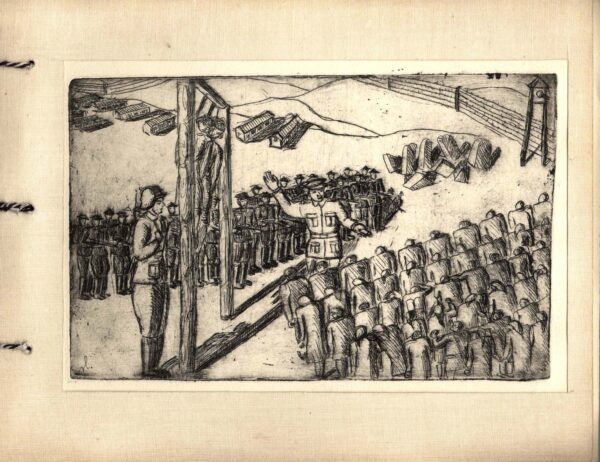

Panel 10 (Figure 12): The final panel in the album represents an event often recounted by the inmates of Plaszów, when Goth ordered two female prisoners to be hanged on the Appelplatz for going back to the ghetto without permission. In the background of this ‘demonstration’ by the over-scaled Nazis, another type of stone appears: gravestones. Plaszów had been built on the site of two Jewish cemeteries, and its gravestones had been strategically repurposed to pave the so-called ‘SS road’ so that inmates were forced to trample over the memory of their ancestors on their way to and from work.

‘There were people, who couldn’t suffer, who knew that the end in the concentration camp is the grave. They risked and flew away. The most of them were caught and had a cruel death. They were hanged. The picture shows the first execution in our camp. Two girls flew away from the camp to the ghetto, when it was still existing. They were caught and hanged to show the power and cruelty of the german rascals. We all had to look at, and to take it in mind. And we shall not forget it for ever. Afterwards were people hanged for other stupid reasons. Once a boy of 17 had probably been heard singing a russian song. He was hanged’.

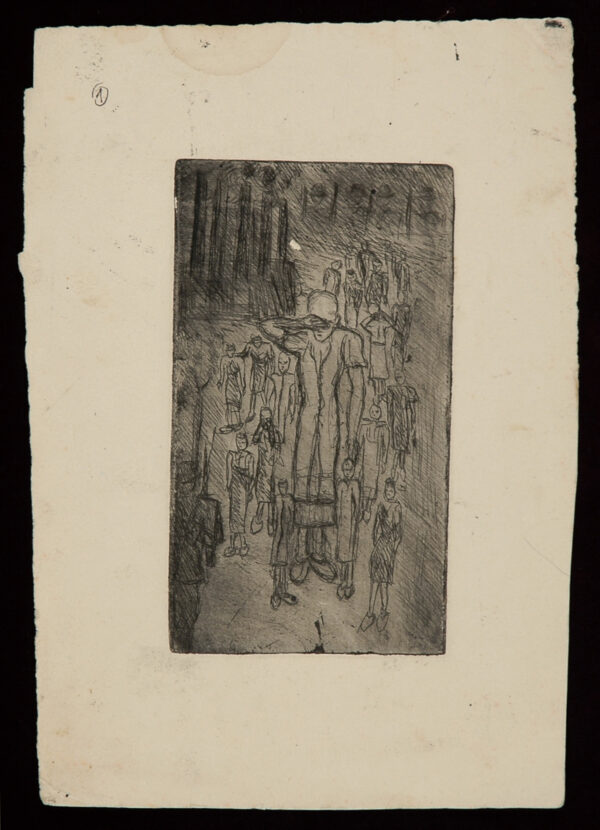

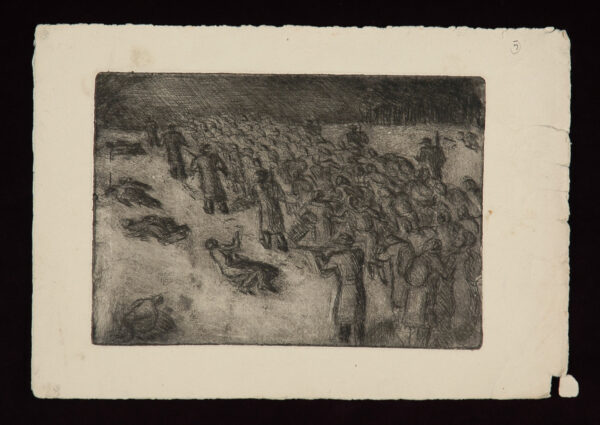

Lichter’s album does not close with a ‘proper’ conclusion, with an image of her liberation and ‘return to life’; it does not offer up either a condensed emblem or a closing to mark the war’s end, as most early postwar graphic narratives do: with piles of dead bodies or symbols of destruction. It leaves off, with references to other hangings that followed, ‘afterwards’ ‘for other reasons’. Given its title, 1939-1945, it is safe to assume that Lichter intended to add more texts and images in order to extend the narrative beyond 1943 and her internment in Plaszów. Indeed, because it is a handmade thing rather than a readymade, prefabricated album with a set number of pages, it could have accommodated many more prints on the remaining blank pages. In fact, Lichter made two other etchings during this period that didn’t make the cut. Archived today in the Yad Vashem art collection, ‘After the Selection’ and ‘The Ruthless Trek’ (YV 8690 and 8692) represent later events: her arrival in Auschwitz and her departure from it, on a Death March (Figures 13 and 14).27

Figure 13. Regina Lichter-Liron, After the Selection, 1946-1949, engraving, 25.1x17.6 cm, Collection of the Yad Vashem Art Museum, Jerusalem, no. 8690. Gift of Professor Trude Dotan.

Figure 14. Regina Lichter-Liron, The Ruthless Trek, 1946-1949, engraving, 17.6x25.5 cm, Collection of the Yad Vashem Art Museum, no. 8692. Gift of Professor Trude Dotan

Throughout, Lichter foregrounds the act of looking. In the texts, directives are strategically used to focus the viewer’s attention and explicate scenes, but they also highlight what I would call ‘coerced vision’: the way in which looking was enforced as yet another tool of Nazi oppression. Addressing her reader in the second person, singular and/or plural, she indicates: ‘You see women carrying heaving pieces of wood and heavy stones carried by men’; ‘You see the S.S. watching and hitting the men’; ‘You see naked men, women and children’. Here, the text is used to describe and support the image: ‘The picture shows the first execution in our camp’. Her brother cries out, traumatised by ‘What I have seen’. Elsewhere, she stresses how Nazi officers commanded the inmates to look at the hanged women. She writes, ‘We all had to look at, and to take it in mind [commit it to memory]. And we shall not forget it for ever’ (my emphasis).Throughout, Lichter’s textual emphasis on looking is staged pictorially: figures shield their faces or cover their eyes with their hands: her mother, when she says goodbye to her father and again when in front of the soldier and her brother face down on the bed. So too, in the ‘flagellation’, the huddle of women awaiting their turn on the torture block, turn their gazes away from the spectacle. Before the firing squad in panel 8, they avoid eye contact with their perpetrators. Lichter, thus, shows us the difficulty of seeing and witnessing in real time. In response to the absence of documentation and the Nazis’ own systematic attempts to erase evidence of their crimes, she foregrounds what could not be seen at the time: what was too traumatic, or too dangerous to eyewitness. Sara R. Horowitz has written eloquently of the ‘wounded tongue’; Lichter stages the trauma of the ‘wounded eye’28 which captures the paradoxical nature of visual testimony, balanced between the need to look and the dangers of doing so.29

Pressing Matters

There is something remarkably poignant about the fact that Lichter turned to printmaking for her Holocaust testimony, for her album covers a period of time when she lived, as Audre Lorde wrote, ‘imprinted with fear’. After the war, as we shall see, she used painting – richly coloured, unctuous pastoral Italian landscapes – for the present; print – sharp, detailed, monochromatic scenes of Nazi rape, torture and murder – was for the traumatic past. Above and beyond its reproducibility, ‘print uniquely evokes the practice of memory in both function and concept’, as Andrew Saluti has written.30 Indeed, our language about memory is grounded in metaphors of print.31 We say something made an ‘impression’ on me; it was ‘imprinted’ on my mind or ‘engraved’ in memory. Like the ‘pull’ of the ink from the matrix onto paper, memories are ‘pulled’ or extracted. Its temporal and material dimensions stage the work of memory; from encoding to storage to retrieval, prints are elaborated over time – from inscribing to effacing to imprinting.

Above all, print depends upon pressure. Lichter’s prints are centred on pression – and all its cognates: suppression, repression, depression, expression, impression.32 Her prints register her emotional state of being ‘under pressure’ and record the oppression she experienced, and they convey the exertion of force it took to both physically and psychically make the work. Affect – what presses us to feel – is not only her testimony’s subject matter, as conveyed in words, images, framing and sequence, but her ‘facture’.

Derived from the Latin factura (meaning making or manufacture), ‘facture’ refers to the way a thing is made materially. Although ‘often neglected in social and cultural histories of art that focus narrowly on subject matter’33, facture reveals more than facts. The embodied aspects of Lichter’s testimony (like those conveyed in the tone of voice or physical gestures of speech acts) convey emotion.

Of all the print techniques, Lichter turned specifically to etching. That she did so is significant, for this technique was used in what is often described as the very first anti-war statements in European art: Jacques Callot’s Les Misères et les Malheurs de la Guerre (1633), a series of 18 etchings that chronicle the destruction unleashed on civilians during the Thirty Years’ War, and Francisco Goya’s Disaster of War (1810-1820), a series of 82 etchings (in addition to aquatint, engraving and drypoint) agitating against the violence of the Peninsular War. Etching was also the print technique that the German Jewish artist Lea Grundig chose for two militantly anti-fascist series she made in the mid-1930s: Unterm Hakenkreuz (Under the Swastika) of 1936 and Der Jüde ist schüld (The Jew Is Guilty!) of 1935-1936.

Whether by accident or – as I am suggesting – by design, Lichter gravitated toward a particularly ‘violent’ technique for the representation of violence and traumatic memory. Etching is painstaking, time-consuming and laborious; it requires control and concentration to make and close proximity to view. Unlike the relief technique of the woodcut, which renders simple, bold, flat patterns with rough-hewn effects, etching offers precision and meticulous detail with fine lines. But, above all, this is a technique that acutely registers violence as it is drawn on the body by the body. Not only does the etched line ‘traumatise’ (meaning to wound or pierce) the metal matrix, but the mordant acid cuts and ‘wounds’ it further. During the Holocaust, Lichter experienced ‘imprinting’ not as a metaphorical act but as a literal one, perpetrated against her body by the Nazis: in Płaszów, where female bodies were scarred by the marks of whip slashes that cut through flesh, leaving scars and welts, and in Auschwitz, where she was branded with a tattoo number.

‘Double Jeopardy’34

Regina (Rachel) Lichter was ‘never meant to survive’, as Audre Lorde phrased it. As a Jew and a woman, she was subjected to a ‘double jeopardy’ during the Holocaust. Having exhausted my biographical research, a month before I submitted this essay to the editors, I decided to Google her name and discovered, much to my surprise and delight, a website devoted to her that had just been published a month earlier by the relatives and descendants of Fulvio Sbrighi, her longtime partner.35 Sbrighi inherited her estate after her death on the 20th of June, 1995, and he not only preserved much of her oeuvre but also her personal archive of press clippings, documentation, photographs and correspondence that has allowed me to flesh out the details of her life.36 Lichter was born on the 20th of December 1920, in the small town of Uhnów, Poland (today Uhniv, Ukraine) in the Rava Ruska district of Eastern Galicia.37 Her parents were Nachum and Golda Lichter and she had a younger brother named Abraham. All three, pictured in the album, perished in the camps. When Germany invaded Poland in September 1939, Lichter was only 18 years old and had just graduated from the Jewish Lyceum in Kraków. She and her family found themselves trapped in the Kraków ghetto. Her formal artistic training began there, under Abraham Neuman, who was murdered by the Nazis on the 4th of June 1942, as he was being deported on a transport to the Bełżec death camp.38 In that same year, she was put to work in the nearby Plaszów concentration camp.39 According to a Nazi document archived at the Jewish Historical Institute, at the end of August, she was transferred back to the ghetto because of sudden illness on the 27th of August 1943.40

In October 1944, she was deported to Auschwitz-Birkenau, where, so her biographer writes, ‘After a week, the SS came to take them to the ultimate sacrifice [in the gas chambers], but saying they had the wrong group, they brought them back. Luckily, a few days later, they asked for some girls who could draw. Regina volunteered and was immediately transferred to Auschwitz to make enlargements of drawings taken from postcards, which were then resold in Germany’.41In a letter she wrote in the 1970s, Lichter acknowledged that her artistic skills ‘probably’ saved her, as she made ‘portraits and drawings for our Kapo’.42 So too, Carlo Levi, the famous Jewish Italian writer, painter, and antifascist activist, noted in his preface to Lichter’s subsequent album of prints Immagini from 1962 that:

‘It was her fluency with a pencil that saved Regina. At Plashuoff [Płaszów] it was she who was selected to mould a plastic model of the camp as the Nazis engineered it. And then at the infamous Auschwitz […] her talent gained her a branded arm: number A 26412. The number represented life, even if temporary, Regina said […] The work designated for her was specialised: the drawing of ration tickets. These were for distribution to the Nazi personnel. She recalls the black market that circulated within the Nazi framework. Her immediate superior had her draw additional ration coupons above the quota for his private sale to SS men. Regina was flooded with additional work by Nazis who brought to her photographs of which they desired enlargements or duplicates or coloured versions in oils. She was traded better food and additional clothing for her services’.43

If Lichter had begun studying art in the ghetto, the camps were her true training field, and she survived largely thanks to her ‘gifted hands that kept [her] from becoming a Holocaust statistic’.44

With the Russian advance in January 1945, Lichter was sent on a Death March when SS units liquidated the camp and evacuated approximately 56,000 prisoners from the camp complex, in columns heading west. For eleven days, she was forced to march from camp to camp, watching her peers dying of hunger, cold, disease and shootings. Eventually she arrived at Ravensbrück, where she finally received some soup and mouldy bread to be divided among the women. From there, the group was transferred on foot and by armoured trains to the Neustadt-Glewe concentration camp where she was liberated on the first of May 1945.

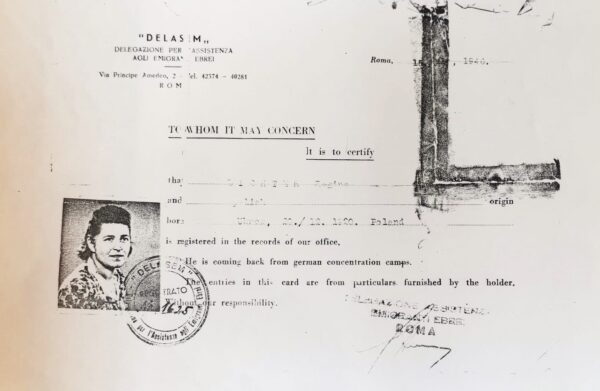

After liberation, Lichter returned to Poland with some other young Polish women, but, as she related, she ‘found no one, not even distant relatives’.45 With the help of the AJDC (American Joint Distribution Committee, hereafter referred to as the JDC), she emigrated to fulfil her ambition to become a full-fledged artist, traversing Europe to arrive in Italy, a country she described as ‘always marked by those who are interested in art’.46 By August, Lichter was in Milan and in September she filed papers with the JDC in Rome.47 Throughout this period, she regularly received financial support and aid from HIAS (the Hebrew Immigrant Aid Society) in Florence48 and from DELASEM (Jewish Refugees Relief Committee), as evidenced in her registration cards held in the JDC archives: in January 1946, while she was in Naples, and in March 1946, when she was in Modena (Figure 15).49 Carlo Levi later noted that, ‘With freedom in 1945, all her family lost, Regina just had a dream to call her own. And that was to study art in Italy’.50

Figure 15. Lichter’s registration card for DELASEM (Delegazione per l’Assistenza degli Emigranti Ebrei), the Jewish Refugees Relief Committee, Rome, 1946. Artist’s estate.

One of the most important art displays in the history of the Jewish people’

Lichter’s 1939-1945 album emerges out of a vibrant community in transit in her newly adopted home in Italy. As Chiara Renzo has noted in her study of Jewish Displaced Persons in Italy, 1943-1951, Holocaust survivors organised and participated in a wide range of cultural activities that were supported by relief and rescue agencies. The OJRI (Organization of Jewish Refugees in Italy) was established in the fall of 1945, and, in the summer of 1946, the same organization founded an art department, which organised dramatic and musical activities, as well as art exhibitions.51 Chief among these initiatives was the Kibbutz Omanut (meaning ‘art’ in Hebrew) supported by the JDC. It hosted 35 Jewish DP painters, sculptors, musicians, singers, dancers, writers and journalists in Castel Gandolfo, Pope Pius XII’s summer residence near Rome. They were tasked with preparing material, training instructors, and organizing competitions and a wide array of cultural and artistic activities for DPs that toured the camps and were advertised in newspapers such as Baderech (On the Way) and In gang: khoydesh-zhurnal far literatur un kunst (On the Move: Monthly Newspaper of Literature and Art).

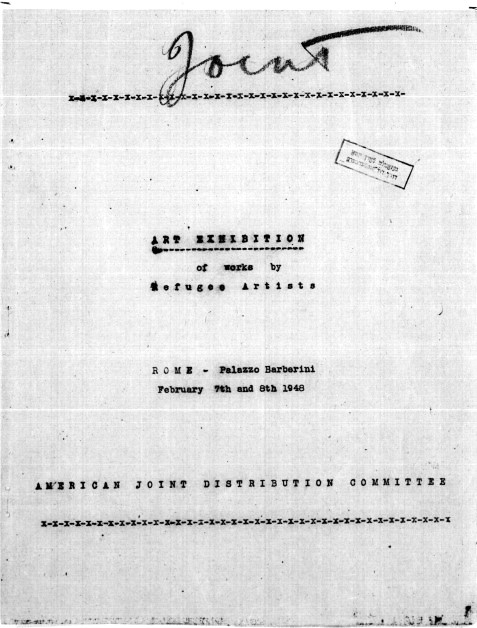

Figure 16. Catalogue of “Art Exhibition of Works by Refugees Artists,”

February 7-10, Palazzo Barberini, Rome.

From the 7th to the 10th of February 1948, Lichter participated in a group exhibition at the Palazzo Barberini in Rome which was ‘visited by 1,000 people in four days’52: Art Exhibition of Works by Refugees Artists (Figure 16).53 Sponsored by the JDC, it showcased over 100 works by eighteen Jewish survivors: paintings, drawings, postcards, interior design, ceramics, fashion design, and wood carvings. The catalogue, archived today at YIVO, included short biographies of the artists, an itemised list of the works displayed, as well as a foreword outlining the JDC’s role in promoting the exhibition as one of its ‘welfare activities’ of assistance ‘for students in all phases of cultural life’54:

‘This exhibition is being sponsored in order that the directorate and other interested bodies may have an opportunity of seeing the work of the refugee artists and also to bring to public notice the abilities of these students and artists’.55

All of the artists were, the catalogue stressed, ‘displaced persons, most of them are still living in displaced persons camps’. They included ‘recognised artists’ like Arno Stern, Samuel Zajdensztadt, Albert Alcalay and Michel Fingesten but also eleven ‘art students’, like Lichter, who were enrolled in various art schools, such as the Accademia di Belle Arti in Rome.56

Lichter was one of only seven women artists in the group57 and one of the very few who submitted works dealing with the Holocaust. The sculptor Laszlo Moskovicz exhibited two works, The Way to the Crematorium and The Jewish Renaissance; Samuel Zajdensztadt included five works that explicitly addressed the traumatic past: Jewish Elegy, The Past Spent in Poland, Ghetto Type, Jewish Wedding, and Warsaw Ghetto. Albert Alcalay exhibited two Holocaust-related drawings: The Persecuted and The Wanderers. Lichter was described in the catalogue as a ‘student of painting’ who had ‘started her studies in Kraków prior to the war’ before being ‘deported to Auschwizt [Auschwitz] and other concentration camps and after liberation came to Italy and is now studying at the Academy of Fine Arts in Turin’. She exhibited five landscape paintings of Italy: two of Selvino and one each of Genoa, Venice and Saluzzo. But, alongside these, Lichter included ‘seven Xylographies from a concentration camp in Germany’ – which is a grossly inaccurate description, because they were made of, not from a camp and, according to my research, she never made woodcuts. These seven ‘xylographies’ (another word for woodblock printmaking) were, in fact, linocuts.

After its Rome debut, Art Exhibition of Works by Refugees Artists travelled abroad to the United States, thanks to a committee from the Los Angeles Delegation of the UJA (United Jewish Appeal) that had attended the show and acquired all the works during their mission to provide aid to the DPs in Italy. The entire collection was exhibited in late December 1948 at the Sarah Singer Art Gallery in the Beverley Fairfax Jewish Community Center (18th of December 1948 – 16th of January 1949).58 All of the works – a total of 107 paintings, sketches and prints – were for sale, with proceeds benefiting the United Jewish Welfare Fund. The Los Angeles Times covered the exhibition under the header ‘Works of DP Artists in Italy Exhibited Here’.59 And the reporter of the B’nai B’rith Messenger advertised the ‘Tremendous Story Told in Nazi Survivors’ Art’ as ‘perhaps, one of the most important art displays in the history of the Jewish people’.60 Both reviews singled out Lichter, noting her skill and the power of her prints ‘to forcibly express the horror many of them knew in cc [concentration camps]’.61 Praised as ‘certainly worthy of the art connoisseur’, her prints were compared to ‘a series of chapters in a novel depicting the fears, suffering and uncertainty which the average DP had to conquer and then go forward and lick life itself’ (my emphasis).62

At some point in the late 1940s – perhaps during her studies at the Academy in Rome and certainly before the DP exhibition of 1948 – Lichter abandoned etching and turned to a different printmaking process: linocut engraving. Which is to say: she shifted from intaglio to relief printmaking, where it is the raised surface left behind on the matrix that is inked and printed. With this new technique, style and content change. Because linoleum (a rubbery, vinyl material) is a softer, more supple material, and thus easier to cut or carve into than metal, the precision of her scratched line becomes more fluid and fluent and her image more condensed and abstracted. What is gained in the process is modernist abstraction; what is lost is anecdotal detail, as the awkward discrepancies in scale, spatial irregularities, and perspectival ‘errors’ are retooled, and naturalism is pulled towards the emblematic and allegorical. Memory becomes fixed into a single, core emblem, isolated and centred on the page. More significant, she excises all the personal sections of her early ‘unbelated testimony’ (her moving memories of close family members), as well as the highly charged signs of sexual violence she endured and witnessed.

Figure 17. Jeanette R. Herschaft, “Concentration Camp Experiences

Produce an “Anne Frank” of the Linoleum Block,” The National Jewish Post and Opinion (Indianapolis, Indiana) September 15, 1961.

Over the next thirty years, Lichter exhibited and reworked the series several times, insistently committed to the value of ‘imagetext’ testimony.63 What she called her ‘book of memories’ was finally published in 1962 under the title Immagini (Images), with an introduction by Carlo Levi and additional linocuts, now numbering 19.64 Critics heralded her work, dubbing her the ‘Anne Frank of the Linoleum Block’ (Figure 17).65 A second edition was published in 1978 by Beniamino Carucci Editore (Assisi/Rome), with an author’s preface, and extended (and edited) textual captions in four languages: Italian, French, English, Hebrew (Figure 18).66

Figure 18. Regina Lichter-Liron, Immagini (Images), 19 linocuts, introduced by Carlo Levi (Rome: Edizione “Israel,” 1962) in Italian, English, French, 40 x 29,5 cm. Another edition was published by Beniamino Carucci Editore in 1978-9, with an author’s preface and extended textual captions in four languages, including Hebrew. Artist’s estate.

Past Imperfect: ‘The Wounds That Are Still Open’

In 1979, Lichter participated in a colloquium alongside Primo Levi that was devoted to the question of ‘Who Is Promoting Anti-Semitic Hatred?’ which was held at the Sala Borromini in Rome and sponsored by the Italian Federation of Jewish Youth. In his review of the event for the newspaper La Stampa, Levi noted the presentation by Lidia Rolfi, who wrote Le donne di Ravensbrück (The Women of Ravensbrück) and a talk by Regina Lichter who ‘spoke of the difficulties of reintegration and the wounds that are still open’.67 Lichter herself had alluded to these ‘open wounds’ a year earlier, in 1978, in the author’s preface she wrote for the new edition of Immagini. There, she acknowledged that ‘We who have survived the camps, although we have returned to the living, cannot shake off the images and memories of those days of horror’; ‘After all these years, it is difficult to write about the past that is practically forgotten’.68

Much of my intellectual labour has been, as Saidiya Hartman describes her own, ‘devoted to reconstructing the experience of the unknown and retrieving minor lives from oblivion’ as a ‘way of redressing the violence of history, crafting a love letter to all those who had been harmed’.69 In searching for Lichter, I found others populating the margins, women whose footprint in scholarship is small, but whose labour can be largely felt: women artists who might have crossed paths with her, shared her experience of loss and even some of her circumstances, and then spent their early postwar years trying to testify to these through art. Had she shared a barrack with Zofia Rosenstrauch or Agnes Lukács in Auschwitz? Had she passed by Edith Bán (Kiss) in Ravensbrück? Or Ella Liebermann (Shiber), who, like Lichter, was in Auschwitz and sent on a Death March towards Ravensbrück and later Neustadt-Glewe. All but erased from official documents and Nazi records, Lichter could have been relegated to a footnote in the grand narrative of history. But through her album she gave witness to the power of art to commemorate the past, figure traumatic memories, and offer a way forward to those who live ‘at once before and after/ seeking a now that can breed futures’, as Lorde phrased it. With her imprinted ‘testimonies’, Lichter wrote that,

‘I wanted to do two things: I wanted to create a monument for all those dead in the camps, in this terrible Holocaust that nobody could have imagined in the 20th century. And I wanted that nobody would forget’.70

When I began writing this paper, in the summer of 2023, the things depicted and described in Lichter’s album 1939-1945 seemed to belong to a past resolutely behind us, where, as she writes in her halting English, ‘there was everywhere hunting for Jews’: women sexually violated, mothers separated from their children and forced to eyewitness their torture and murder, Jewish homes invaded and destroyed, men deported, women taken away as hostages, families ripped apart, and mass executions at close range by rifle. With the pictures and stories coming out of Israel over the last few weeks, after the 7th of October, Lichter’s ‘images’ and ‘testimonies’ now appear to belong to the past imperfect – the tense we use to describe a past action or a state which is incomplete, lacking a specific endpoint in time – or perhaps even the present ‘perfect’, which designates an action or situation which began in the past and continues, even into the present.

*This essay is part of a manuscript in progress entitled “Who Will Draw Our History? Early Holocaust Graphic Narratives by Jewish Women Survivors,” funded by the Hadassah Brandeis Institute, the Dedalus Foundation and the Mémorial de la Shoah. My deepest thanks to Davide Betti and his extended family for their generosity in sharing documents about Lichter. I am grateful to the Yad Vashem Art Museum for permission to reproduce Lichter’s work. Stefanie Fischer at YIVO and Renata Piątkowska at the Żydowski Instytut Historyczny in Warsaw assisted my archival research immeasurably.

Bibliography

Alcalay, Albert. The Persistence of Hope: A True Story. Newark, DE: University of Delaware Press, 2007.

Amishai-Maisels, Ziva. Depiction and Interpretation. Oxford: Pergamon, 1993.

Auslander, Leora. “Beyond Words.” American Historical Review (October 2005): 1015-1045.

Barthes, Roland. Image, Music, Text. Translated by Stephen Heath. NY: Hill and Wang, 1978.

Beal, Frances M. “Double Jeopardy: To Be Black and Female.” New Generation 51 (Fall 1969): 28. Accessed November 27, 2023: http://www.hartford-hwp.com/archives/45a/196.html.

Blatter, Janet, and Sybil Milton. Art of the Holocaust. New York: Orbis, 1981.

Campt, Tina M. Listening to Images. Durham and London: Duke University Press, 2017.

Chute, Hillary. Disaster Drawn: Visual Witness, Comics, and Documentary Form. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2016.

E. L. R., “Tremendous Story Told in Nazi Survivors’ Art.” B’nai B’rith Messenger (Los Angeles, CA), December 24, 1948.

Foucault, Michel. “Lives of Infamous Men.” In The Essential Foucault, edited by Paul Rabinow and Nikolas Rose. New York: New Press, 2003.

Hartman, Saidiya. Wayward Lives, Beautiful Experiments: Intimate Histories of Social Upheaval. New York, NY: W.W. Norton and Co., 2019.

Herschaft, Jeanette R. “Concentration Camp Experiences Produce an ‘Anne Frank’ of the Linoleum Block.” The National Jewish Post and Opinion (Indianapolis, Indiana), September 15, 1961.

Hirsch, Marianne, and Leo Spitzer, “Testimonial Objects: Memory, Gender, and Transmission.” Poetics Today 27, no. 2 (2006): 353-383.

Horowitz, Sara R. “The Wounded Tongue: Engendering Jewish Memory.” In Shaping Losses: Cultural Memory and the Holocaust, edited by Lori Hope Lefkowitz and Julia Epstein. Urbana and Chicago, IL: University of Illinois Press, 2014.

Jockusch, Laura. Collect and Record!: Jewish Holocaust Documentation in Early Postwar Europe. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2012.

Katin, Miriam. Letting It Go. New York: Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 2013.

Klemperer, Victor. I Will Bear Witness: The Diary of the Nazi Years 1933-1941, vol. 2. New York: Random House, 1998.

LaCapra, Dominick. Representing the Holocaust: History, Theory, Trauma. Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press, 2016.

Levi, Primo. “Who Is Promoting Anti-Semitic Hatred.” La Stampa, March 13, 1979. In The Complete Works of Primo Levi, edited by Ann Goldstein, vol. 3. New York: Liveright/W.W. Norton & Company, 2015.

Lichter-Liron, Regina. Immagini. Rome: Edizione “Israel,” 1962.

Lichter-Liron, Regina. Immagini. Assisi/Rome: Beniamino Carucci Editore, 1978.

Lichter-Liron, Regina. Public talk at the Antica Libreria Croce, Rome, 1978 on the occasion of the release of Immagini. Recorded and broadcast on TV in “Diario Romano.” Accessed, November 15, 2023: https://youtu.be/Tj6Qs4c01OU?si=dIGxWK1wiYaJrsMB

Lichter-Liron, Regina to Dr. Ferrara, undated letter from the 1970s. Family archive, Fano, Italy.

Lorde, Audre. “A Litany for Survival,” The Collected Poems of Audre Lorde. New York: W. W. Norton & Company, Inc. 1997.

Mitchell, W.J.T. Picture Theory. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1994.

Novitch, Miriam, Lucy Dawidowicz, Tom L. Freudenheim Spiritual Resistance: Art from Concentration Camps 1940-1945. Western Galilee: Beit Lohamei Haghetaot and New York: Union of American Hebrew Congregations, 1981.

Oberti, Antonio. “Biography of Regina Lichter-Liron” in Arte Italiana per il Mondo. C.E.L.I.T., Centro librario italiano di Torino, 1995.

Perry, Rachel E. “In Search of Elżbieta Nadel’s The Black Album of 1946.” EHRI (European Holocaust Research Infrastructure) Document Blog, June 2023: https://blog.ehri-project.eu/2023/07/04/elzbieta-nadels-black-album/#Remembering_to_Draw_Images_from_Home.

Perry, Rachel E. “Inserting Hersh Fenster’s Undzere farpainikte kinstler (Our Martyred Artists) into Art History.” Images: A Journal of Jewish Art and Visual Culture 14 (1) (2021): 109-135.

Perry, Rachel E. “Nathalie Kraemer’s Rising Voice.” Ars Judaica 15 (2019): 95–146.

Perry, Rachel E. “Moving Images, Moving Subjects”: Telepathos in Graphic Albums Created in the Yishuv, 1940-44. Holocaust and Genocide Studies (Spring 2024).

Perry, Rachel E. “Not by Words Alone: Early Holocaust Graphic Narratives as a ‘Minor’ Art.” Images: A Journal of Jewish Art and Visual Culture (2023).

Pollock, Griselda. Differencing the Canon: Feminism and the Writing of Art’s Histories. London: Routledge, 1999.

Presiado, Mor. “A New Perspective on Holocaust Art: Women’s Artistic Expression of the Female Holocaust Experience (1939–49).” Holocaust Studies: A Journal of Culture and History (2016): 1-30.

Presiado, Mor. “Multi-Generational Memory of Sexual Violence during the Holocaust in Women’s Art.” In War and Sexual Violence: New Perspectives in a New Era, edited by Sarah K. Danielsson, 147-182. Leiden: Brill - Schönigh, 2019.

Renzo, Chiara. Jewish Displaced Persons in Italy 1943–1951: Politics, Rehabilitation, Identity. London: Routledge, 2023.

Renzo, Chiara. “Where Shall I Go?”: The Jewish Displaced Persons in Italy (1943-1951). PhD diss., Universities of Florence and Siena, 2016.

Roberts, Jennifer L. “Contact: Art and the Pull of Print.” The 70th A. W. Mellon Lectures in the Fine Arts, National Gallery of Art, Washington DC, 2020. Accessed, September 15, 2023: https://www.nga.gov/research/casva/meetings/mellon-lectures-in-the-fine-arts/roberts-2021.html

Roberts, Jennifer L. “The Power of Patience: Teaching Students the Value of Deceleration and Immersive Attention.” The Harvard Magazine, November-December 2013. Accessed, November 1, 2023: https://www.harvardmagazine.com/2013/10/the-power-of-patience.

Rosen, Alan. The Wonder of Their Voices: The 1946 Holocaust Interviews of David Boder. New York: Oxford University Press, 2010.

Saluti, Andrew. ‘The Impression of Memory: Printmaking and The Process of Shared Experience.” Trigger Points (2016): 4-21.

Saxton, Libby. Haunted Images: Film, Ethics, Testimony and the Holocaust. London and New York: Wallflower Press, 2008.

Sujo, Glenn. Legacies of Silence: The Visual Arts and Holocaust Memory. London: Imperial War Museum and Philip Wilson Publishers, 2001.

Tishman, Shari. Slow Looking: The Art and Practice of Learning Through Observation. New York: Routledge, 2017.

Wieviorka, Annette. “The Witness in History.” Poetics Today 27, no. 2 (2006): 385-397.

“Works of DP Artists in Italy Exhibited Here.” The Los Angeles Times, December 19, 1948.

Yaeger, Patricia. “Testimony Without Intimacy.” Poetics Today 27, no. 2 (2006): 399–423.

YIVO, Catalogue of Art Exhibition of Works by Refugees Artists, 1948, Folder 373, Roll 26, Frame 996, Record Group: 294.3, Collection: Displaced Persons Camps and Centers in Italy, 1945-49, Series 6: Organizations.

Zemel, Carol. “Enduring Witness: David Olère’s Visual Testimony.” In Testimonies of Resistance: Representations of the Auschwitz-Birkenau Sonderkommando, edited by Nicholas Chare and D. Williams. Oxford, New York: Berghahn Books, 2019).

Zurier, Rebecca. “Facture.” American Art, 23, no. 1 (2009): 29-31.

- Audre Lorde, ‘A Litany for Survival’, The Collected Poems of Audre Lorde (New York: W. W. Norton & Company, Inc. 1997). ↩︎

- Laura Jockusch, Collect and Record!: Jewish Holocaust Documentation in Early Postwar Europe, (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2012), p. 11. ↩︎

- Marianne Hirsch and Leo Spitzer, ‘Testimonial Objects: Memory, Gender, and Transmission’, Poetics Today 27 (2) (Summer 2006), 353-383. ↩︎

- Leora Auslander, ‘Beyond Words’, American Historical Review (October 2005), 1015-1045. ↩︎

- Alan Rosen, The Wonder of Their Voices: The 1946 Holocaust Interviews of David Boder (New York: Oxford University Press, 2010), p. vii. ↩︎

- Michel Foucault, ‘Lives of Infamous Men’ (La vie des hommes infâmes) was published in Les Cahiers du chemin) in 1977 as the preface to a book that was never published. It is reprinted in The Essential Foucault, eds. Paul Rabinow and Nikolas Rose (New York: New Press, 2003), p. 284. ↩︎

- I discovered Lichter’s work in a number of other collections: in Israel, at the Ghetto Fighters’ House and the Mishkan at Ein Harod and, in Italy, at the Museo Parisi Valle and the Lombardia Beniculturali. ↩︎

- I am borrowing the term from Hillary Chute, who describes contemporary graphic narratives in this way. See her Disaster Drawn: Visual Witness, Comics, and Documentary Form (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2016). The term ‘imagetext’ was formulated by W. J. T. Mitchell to designate ‘composite, synthetic works (or concepts) that combine image and text’. See Mitchell, Picture Theory (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1994), p. 89. ↩︎

- Griselda Pollock, Differencing the Canon. On canonization in Holocaust studies, see chapter 1, ‘Canons, Texts, And Contexts’ of Dominick LaCapra’s Representing the Holocaust: History, Theory, Trauma (Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press, 2016). ↩︎

- I refer to her throughout as Regina Lichter, as she presented herself on official documents and papers in the postwar period, although later in life she was known as Lichter-Liron. It is not clear why or when exactly she took this additional surname. ↩︎

- It was donated on the 17th of August 1994 by Shimon Rubinstein, director of the Yad Ben-Zvi, which was founded in 1947 for the study of the Jewish communities of the land of Israel and the Middle East, to the director of the Yad Vashem Art Museum, Irit Salmon. See https://www.archives.gov.il/product-page/44629. Its provenance, how it entered their archive, remains a mystery. ↩︎

- Janet Blatter and Sybil Milton, Art of the Holocaust (New York: Orbis, 1981); Ziva Amishai-Maisels, Depiction and Interpretation (Oxford: Pergamon, 1993); Miriam Novitch, Lucy Dawidowicz, Tom L. Freudenheim Spiritual resistance: art from concentration camps 1940-1945 (Western Galilee: Beit Lohamei Haghetaot and New York: Union of American Hebrew Congregations, 1981); and Glenn Sujo, Legacies of Silence: The Visual Arts and Holocaust Memory (London: Imperial War Museum and Philip Wilson Publishers, 2001). ↩︎

-

Mor Presiado, ‘A new perspective on Holocaust art: women’s artistic expression of the female Holocaust experience (1939–49)’, Holocaust Studies: A Journal of Culture and History (2016), 1-30, 19. The same print is used, again, as figure 8.6, in her expanded article, ‘Multi-Generational Memory of Sexual Violence during the Holocaust in Women’s Art’ in War and Sexual Violence: New Perspectives in a New Era (Ferdinand Schöningh, 2019), pp. 147-182.

Presiado’s description of the work is unfortunately riddled with errors. She writes that ‘Lichter-Liron’s Flagellation from “The Album 1939 to 1945”, painted in 1946-49 represents one of the punishments in Auschwitz’, but the work is, in fact, not titled ‘Flagellation’ (this is a description given to the work by the museum), and it was not ‘painted’ but printed, nor was it created between 1946-49, as the album is clearly dated March 1946. Moreover, the print she reproduces was not from the bound album; it is a separate print (artist’s proof?) that was donated to Yad Vashem by the Israeli archeologist Trude Dotan, set askew on the paper and unsigned. More disconcerting still, the ‘flagellation’ Lichter depicts did not take place in Auschwitz, but in Płaszów. Dotan donated four individual prints to Yad Vashem. Her husband Moshe, a renowned Israeli archaeologist who founded the Archeology Department at the University of Haifa, was born in Kraków a year before Lichter, in 1919, suggesting they might have been personal acquaintances. Dotan’s mother was an artist who held regular salons and exhibitions in her home for Israeli artists. A professor of archaeology at the Hebrew University, Dotan received the Israel Prize for archaeology in 1998. https://jwa.org/encyclopedia/article/dothan-trude. ↩︎

- Griselda Pollock refers to ‘Seeing the Artist or Reading the Picture’, in chapter 5 of Differencing the Canon: Feminism and the Writing of Art’s Histories (London: Routledge, 1999). ↩︎

- A number of scholars have taken up the banner. See Jennifer Roberts’ lecture ‘The Power of Patience’, November 2013, Harvard Initiative for Learning and Teaching; James Elkins, How to Use your Eyes; Shari Tishman, Slow Looking: The Art and Practice of Learning Through Observation (New York: Routledge, 2017). ↩︎

- Patricia Yaeger, ‘Testimony without Intimacy’, Poetics Today 27 (2) (2006), 399–423. ↩︎

- Miriam Katin’s graphic novel Letting It Go opens thus: ‘So, where does a story begin? And if you are inside that story right now, in that situation and it hurts and say you can draw, then you must try and draw yourself out of it’. Miriam Katin, Letting It Go (New York: Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 2013), p. 9. ↩︎

- Saidiya Hartman writes this about the young Black women she studies in Wayward Lives, Beautiful Experiments: Intimate Histories of Social Upheaval (New York, NY: W.W. Norton and Co., 2019), pp. 16-17. ↩︎

- She stated this in a 1978 talk she gave at the Antica Libreria Croce on the Corso Vittorio Emanuele in Rome for the publication of Immagini, a book of prints derived from those in the album 1939-1945. The evening was recorded and broadcast on TV in the program ‘Diario Romano’ and was introduced by Senator Umberto Terracini and supported by Ignazio de Logu and Fausto Coen among others. The recording has been recently uploaded to YouTube: https://youtu.be/Tj6Qs4c01OU?si=dIGxWK1wiYaJrsMB ↩︎

- Annette Wieviorka, ‘The Witness in History’, Poetics Today 27 (2) (Summer 2006), 385-397, 389: ‘The associations of Jewish survivors that had been created were based on simple ties of sociality and mutual aid and did not harbor ambitions to address anyone except those who had lived through the same experience’. ↩︎

- Victor Klemperer, I Will Bear Witness: The Diary of the Nazi Years 1933-1941, vol. 2 (New York: Random House, 1998), p. 357. ↩︎

- Roland Barthes, Image, Music, Text, trans. Stephen Heath (NY: Hill and Wang, 1978), p. 26: ‘The caption […] appears to duplicate the image, that is, to be included in its denotation’. ↩︎

- To give one example of her ‘broken’ English, the introduction reads: ‘The systematical, unic in the whole world, ruinining a nation, millions of defendeless, unable to hide themselves from the barabars was beginning. From this time, every day and hundreds times in one day hundreds of thousands of young, old, mothers and children were muredered in the cruelst way. And like the savages they made use of their corpses, f.i. soap was made of the fat’. Her texts, thus, reveal a great deal about the survivors’ access to knowledge and the purchase of certain rumors (soap made from the victims) within survivor communities. ↩︎

- See Tina M. Campt, Listening to Images (Durham and London: Duke University Press, 2017), pp. 32, 109, and 113. ↩︎

- In fact, Lichter was in art school in Italy during this period. On her report card from the Academy in Rome, dated the 18th of November 1949, she received 28/30 in painting; 29/30 in tecnique del incisione and 30/30 in History of Art. Family archive, Fano, Italy. ↩︎

- Carol Zemel, ‘Enduring Witness: David Olère’s Visual Testimony’, in Nicholas Chare and D. Williams, eds. Testimonies of resistance: Representations of the Auschwitz-Birkenau Sonderkommando (Oxford, New York: Berghahn Books, 2019), pp. 186-188. ↩︎

- In addition to the album, Yad Vashem has four separate etchings, two of which were included in the album (panels no. 6 and no. 9, YV 8691 and 8693) and the two mentioned in the text that were omitted. ↩︎

- Sara R. Horowitz, ‘The Wounded Tongue: Engendering Jewish Memory’, in Shaping Losses: Cultural Memory and the Holocaust, eds., Lori Hope Lefkowitz and Julia Epstein (Urbana and Chicago, IL: University of Illinois Press, 2014), pp. 107-128. ↩︎

- See Libby Saxton, Haunted images: film, ethics, testimony and the Holocaust (London and New York: Wallflower Press, 2008), pp. 92-118. ↩︎

- Andrew Saluti, ‘The Impression of Memory: Printmaking and The Process of Shared Experience’, Trigger Points (2016), pp. 4-21. ↩︎

- On printmaking and Holocaust emotions, see my forthcoming article ‘Moving Images, Moving Subjects’: Telepathos in Graphic Albums Created in the Yishuv, 1940-44’, Holocaust and Genocide Studies (Spring 2024). ↩︎

- See Jennifer L. Roberts, ‘Contact: Art and the Pull of Print’, The 70th A. W. Mellon Lectures in the Fine Arts, National Gallery of Art, Washington DC, 2020. Online at: https://www.nga.gov/research/casva/meetings/mellon-lectures-in-the-fine-arts/roberts-2021.html ↩︎

- See Rebecca Zurier, ‘Facture’, American Art, 23 (1) (2009), 29-31. ↩︎

- ‘Double Jeopardy: To Be Black and Female’ is the title of a 1969 Feminist pamphlet by Frances M. Beal. ↩︎

- See https://reginalichterliron.com/?page_id=26 ↩︎

- Of central importance is Antonio Oberti’s ‘Biography of Regina Lichter-Liron’ in Arte Italiana per il Mondo (C.E.L.I.T., Centro librario italiano di Torino, 1995), which was written based on his interviews with her. Appended to Oberti’s biography is a list of her solo and group exhibitions, the collections that hold her work and the newspapers and journals that reviewed her work. ↩︎

- Her JDC documents list her date of birth as 6/5/20. ↩︎

- She acknowledged Neuman’s tutelage in a letter she wrote to Dr. Ferrara in the 1970s, preserved in the family’s archive in Fano, Italy. Many of Neuman’s works are in the collections of the Jewish Historical Institute: https://delet.jhi.pl/en/search?searchQuery=abraham%20neumann&searchIn=library; https://www.jhi.pl/en/articles/june-4-1942-two-jewish-artists-shot-in-krakow,658 ↩︎

- Her name appears on a List of Jewish Inmates in Plaszów camp compiled between the 24th to the 28th of February, 1943, which is in the Yad Vashem archives: https://yvng.yadvashem.org/nameDetails.html?language=en&itemId=15036857&ind=1 ↩︎

- The Jewish Historical Institute has a Nazi memo from KL Plaszów dated 28.11.43 that specifies that Regine Lichter from the Luftgaukomando was transferred from her work unit to the ghetto, sign. 211/106. ↩︎

- Antonio Oberti, ‘Biography’, in Arte Italiana per il Mondo (C.E.L.I.T., Centro librario italiano di Torino, 1995). ↩︎

- Lichter to Dr. Ferrara, undated letter from the 1970s, family archive, Fano, Italy. She wrote that ‘I was probably saved thanks to my artistic skills, making portraits and drawings for our Kapo’. ↩︎

- Regina Lichter-Liron, Immagini, preface Carlo Levi (Rome: Edizione ‘Israel’, 1962). ↩︎

- Jeanette R. Herschaft, ‘Concentration Camp Experiences Produce an “Anne Frank” of the Linoleum Block’, The National Jewish Post and Opinion (Indianapolis, Indiana), 15 September 1961. ↩︎

- Lichter to Dr. Ferrara, undated letter from the 1970s, family archive, Fano, Italy. ↩︎

- Ibid. The Jewish Historical Institute has a record of her registration survivor card with the Central Committee of Polish Jews (Centralny Komitet Żydów w Polsce - CKŻP), signed in Krakow in 1946. ↩︎

- The card is dated 7/9/45. M.18 - Documentation of the Central Location Index (CLI) of the Joint Distribution Committee (JDC) in New York, no. 71410001: https://collections.arolsen-archives.org/en/search/person/131618181?s=regina%20lichter&t=751750&p=0 ↩︎

- In August, she was in Milan and curiously lists her father Nahum under ‘members of the family abroad’, ‘previously at Theresienstadt’. On another (undated) card from the HIAS agency, she writes his name as Nachum Lieberman from Kraków and her own as Regina Lichter ‘Lieberman’. To the best of my knowledge, her father did not survive and was never in Theresienstadt. I have not been able to explain why she listed his name as Lieberman. The address she gives is Firenze, Delasem, Via Lamarmora 36. ↩︎

- She was given 1,200 and 1,000 lira as part of the JDC’s monthly financial support of individuals in Italy: https://search.archives.jdc.org/multimedia%2FDocuments%2FNames%20Databank%2FPostwar%20Italian%20Aid%2FAdditional%20Links%2FComplete_ItalAid_AR45-54_00074.pdf ↩︎

- Regina Lichter-Liron, Immagini, preface Carlo Levi (Rome: Edizione ‘Israel’, 1962). ↩︎

- Chiara Renzo, Jewish Displaced Persons in Italy 1943–1951: Politics, Rehabilitation, Identity (London: Routledge, 2023). See also Renzo’s dissertation, ‘Where Shall I Go?’: The Jewish Displaced Persons in Italy (1943-1951), Dissertation, Universities of Florence and Siena, 2016, Appendix 18, pp. 306-9. ↩︎

- Renzo, ‘Where Shall I Go?’, p. 236. ↩︎

- YIVO, Catalogue of Art Exhibition of Works by Refugees Artists, 1948, Folder 373, Roll 26, Frame 996, Record Group: 294.3, Collection: Displaced Persons Camps and Centers in Italy, 1945-49, Series 6: Organizations: https://archives.cjh.org/repositories/7/archival_objects/360152. See also AJDC, Letter from A.J.D.C. Rome to A.J.D.C. New York, March 13, 1948, Folder: Italy, Refugees: Art Exhibition, 1948-1949, Reference Code NY AR194554 / 4 / 44 / 9 / 665, Folder Number: 665, Reference Code NY AR194554 / 4 / 44 / 9. ↩︎

- YIVO, Catalogue of Art Exhibition of Works by Refugees Artists, 1948. ↩︎

- Ibid. ↩︎

- Alcalay was born in Paris of Serbian-Jewish parents in 1917. When the war began, he joined the Yugoslavian army and became a prisoner of war in the Ferramonti internment camp in Calabria where he began painting under his fellow inmate, German-Jewish artist Fingesten. He later immigrated to the US and taught at Harvard University, 1960 to 1982, and was one of the founders of its Department of Visual and Environmental Studies (VES). See his memoir, Albert Alcalay, The Persistence of Hope: A True Story (Newark, DE: University of Delaware Press, 2007). Michel Fingesten (Michl Finkelstein) was born in 1884 in the village of Buckovice (Buczkowitz), now part of the Czech Republic, from a Czech-Jewish father and an Italian-Jewish mother. He fled Nazi Germany in 1936 and settled in Milan, where he built a circle of patrons who commissioned and avidly collected his works, until he was arrested in October 1940 and confined to the Fascist internment camp of Civitella del Tronto in 1940, and then transferred in 1941 to that of Ferramonti-Tarsia near Cosenza, Calabria. He died of an infection in Cosenza on October 8, 1943, a few days after the camp was liberated by the British Army. Samuel Zajdensztadt was born in Nowogród. He left Poland at 18 and stayed in the Soviet Union until the end of World War II. From 1946 to 1948 he lived in Italy where he studied at the Academy of Fine Arts of Brera in Milan. He then moved to Paris in 1948 before emigrating to Israel. ↩︎

- In addition to Lichter, six other women exhibited their work: Margherite R. Barta, Eva Deutsch, Maria Farago, Eva Fisch, Eva Fischer, and Mira Kraus. ↩︎

- All of the works, save one drawing, were acquired by the Los Angeles Delegation of UJA which paid $ 2,000,000 to the artists and covered transportation expenses. Chiara Renzo, ‘Where Shall I Go?’, pp. 236-37. ↩︎

- ‘Works of DP Artists in Italy Exhibited Here’, The Los Angeles Times, 19 December 1948. ↩︎

- E. L. R., ‘Tremendous Story Told in Nazi Survivors’ Art’, B’nai B’rith Messenger (Los Angeles, CA), 24 December 1948, p. 24: ‘For the works record an era of Jewish persecution as described by the persecuted themselves, and who, to this very day languish in European DP camps. Here the DP’s have told of their fears, of their nightmarish memories, of their hopes and desires. The exhibition represents a people who refused to die and overcame everything evil had to offer’. ↩︎

- ‘Works of DP Artists in Italy Exhibited Here’, The Los Angeles Times, 19 December 1948. ↩︎

- E. L. R., ‘Tremendous Story Told in Nazi Survivors’ Art’, B’nai B’rith Messenger (Los Angeles, CA) 24 December 1948, p. 24. ↩︎

- She held several exhibitions in Rome, presented by Giulio Turcato at the Tazza d’Oro in Rome in 1950-1952; in 1953 at the Galleria San Marco in Rome, presented by Ignazio de Logu. In Israel, she exhibited with the Painters and Sculptors Association in Israel in January 1950, at the Tel Aviv Museum of Art in 1953, and at the Artists’ House in Jerusalem in 1954. In Paris, she presented her work at the Galerie Palmes in 1957 and at the Centre Culturel UJRE in 1958. ↩︎

- She described it as such in the preface she wrote for the second edition of Immagini (Assisi/Rome: Beniamino Carucci Editore, 1978), n.p.: ‘we must not forget. And this is the aim of my book of memories’. ↩︎

- Jeanette R. Herschaft, ‘Concentration Camp Experiences Produce an “Anne Frank” of the Linoleum Block’, The National Jewish Post and Opinion (Indianapolis, Indiana) 15 September 1961. ↩︎

- I will analyse the transformation of her early, ‘unbelated’ testimony into the later linocuts of Immagini in a forthcoming essay for the volume ‘To tear these images from time’: Exploring Visual Representations from Nazi Camps, Ghettos, and the Holocaust, eds. Verena Krieger and Ella Falldorf (Vienna, Cologne: Böhlau Publishing House, 2024). The Yad Yaari/Moreshet archive has digitised the 1978 edition of Immagini: https://www.infocenters.co.il/yadyaari/pdf_viewer.asp?lang=HEB&dlang=HEB&module=search&page=pdf_viewer&rsvr=9@9¶m=%3Cpdf_path%3Emultimedia/images/moreshet/%D7%90%D7%9E%D7%A0%D7%95%D7%AA%20%D7%95%D7%A1%D7%A4%D7%A8%D7%95%D7%AA/D.7.181/D.7.181.pdf%3C/%3E%3Cbook_id%3E142803%3C/%3E¶m2=&site=yadyaari ↩︎

- Primo Levi, ‘Who Is Promoting Anti-Semitic Hatred’, La Stampa, 13 March 1979, in The Complete Works of Primo Levi, ed. Ann Goldstein, vol. 3 (New York: Liveright/W.W. Norton & Company, 2015). ↩︎

- Lichter, preface, Immagini (Assisi/Rome: Beniamino Carucci Editore, 1978), n.p. ↩︎

- Saidiya Hartman, ‘A Minor Figure’, in Wayward Lives, p. 31. On rescuing marginalised Jewish artists, and particularly women, see my research on the Jewish French artist Nathalie Kraemer, who was deported to Auschwitz and perished there: ‘Nathalie Kraemer’s Rising Voice’, Ars Judaica (March 2020); the Jewish artists deported from France and commemorated by Hersh Fenster’s Yizkor book in 1951: ‘Inserting Hersh Fenster’s Undzere farpainikte kinstler (Our Martyred Artists) into Art History’, Images: A Journal of Jewish Art and Visual Culture (October 2021); and, more recently, the album created by survivor Elżbieta Nadel: ‘In Search of Elżbieta Nadel’s The Black Album of 1946’, EHRI (European Holocaust Research Infrastructure) Document Blog, June 2023: https://blog.ehri-project.eu/2023/07/04/elzbieta-nadels-black-album/#Remembering_to_Draw_Images_from_Home. I use the term ‘minor’ to describe many of the artists working in the immediate postwar period in my recent article, ‘Early Holocaust Graphic Narratives as a Minor Art’, Images: A Journal of Jewish Art and Visual Culture (December 2023). ↩︎

- Lichter, public talk at the Antica Libreria Croce, Rome 1978. ↩︎

Rachel E. Perry