Tytuł

Women Curators Examining Women’s Roles at the ŠKUC Gallery in the 1980s

https://www.doi.org/10.48285/ASPWAW.24501611.MCE.2021.7.3

https://miejsce.asp.waw.pl/women-curators-examining-womens-roles-at-the-skuc-gallery-in-the-1980s/

Abstrakt

The Socialist Federal Republic of Yugoslavia (SFRY) in the 1980s was crowded with collectives, organisations and individuals who fought for autonomous spaces in larger cities where they created thinking hubs brimming with creativity, comradeship and progressive exchange of thought. In Ljubljana, one such location existed at Staritrg 21, a space which the Student Cultural Centre (ŠKUC) acquired in 1978 and where the ŠKUC Gallery currently still operates as part of the same organisation. As various sections (visual art, music, publishing, etc.) operated at the same premises, exhibition-making itself was intertwined with various events and art forms, through which the people behind the ŠKUC also addressed current social issues. The following paper focuses on the work by artistic directors Barbara Borčić and Marina Gržinić during the years between 1982–1985. Gathering their intentions mainly through their writing and selected projects, we clearly see that as artistic directors they created a playground for younger generations to collectively create and produce multifarious forms of artistic expression rooted in social criticism, which is something we can surely learn from even today.

DOI

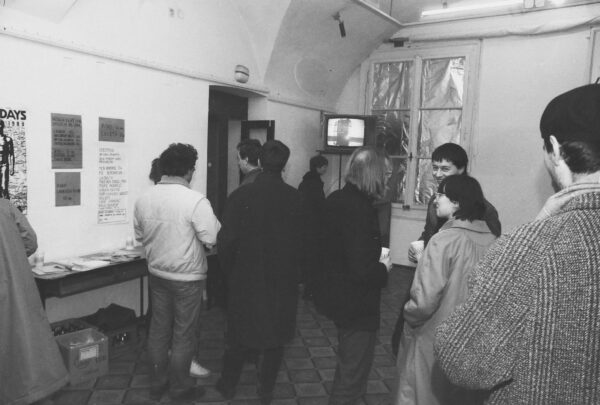

Influential student organisations, non-normative subcultures and local as well as the federal intelligentsia of the former Socialist Federation, together with cultural and intellectual impulses from the West, formed an interesting playground for various models of cooperation and creativity. This was partly due to the unsuccessful economic model of self-management and the struggle of various organisations and individuals for autonomous spaces in larger cities across the federation. Through this, they created thinking hubs brimming with creativity, comradeship, and progressive exchange of thought. In Ljubljana, one such location existed at Stari trg 21, a space which the Student Cultural Centre (ŠKUC) acquired in 1978 and where the ŠKUC Gallery currently still operates as part of the same organisation.

The Slovenian art historian Igor Zabel described the end of the 1970s as a time of a crisis in art, both in the international and Slovenian context. As if artforms and currents had lost energy and that art production had become just another kind of empty repetition and a variation of forms and solutions that had reached their creative peak in the 1960s, or even earlier, and had

now finally been exhausted. 1 In this article, I wish to argue that the continuation of this crisis in the 1980s presented a playground for younger generations to collectively create and produce a variety of artistic expression embedded with social critique. Especially under the artistic directorship of Barbara Borčić and Marina Gržinić at the ŠKUC Gallery between 1982 and 1985.

Ljubljana in the 1980s

The Socialist Federal Republic of Yugoslavia in the first half of the 1980s seemed like a peaceful and stable state. Božo Repe states that although communist patriotism, brotherhood and unity were still being emphasised in society, the real experience of Yugoslavia was very different. Josip Broz Tito’s death in Ljubljana in 1980 marked the beginning of an economic crisis. Due to better organisation and its proximity to the western borders, Slovenia found itself in a better position than the other five republics, which aroused envy and increased disputes with the federal authorities. 2

The mid-1980s were marked by the rise of nationalism, mostly in Kosovo and Serbia, but also in Croatia. This increased the awareness that a new national policy would soon be needed in Slovenia, too. 3 The overall economy was worsening by the year, which was visible in the number of worker’s strikes. 4 Social issues began to be addressed in the alternative circulation, beyond the established channels and possibilities afforded by the state. Until the second half of the 1980s, relations between the authorities and the informal opposition mainly revolved around the question of how much freedom to allow magazines, journalism and cultural activities. To overcome the cultural stagnation, several groups of prominent intellectuals applied to produce independent publications. The first attempt at alternative printing took place in June 1982 under the auspices of the Socialist Alliance of Working People (Socialistična zveza delovnega ljudstva). 5 This became more and more important because the youth and its media gained influence through outlets such as Katedra, Tribuna, Radio Študent and the particularly provocative Mladina. 6

Because of the various media and the ability for young people to actively engage with current issues, many youth clubs and organisations became part of peace, ecological, feminist and other movements, which formed a strong civil society movement in Slovenia in the mid-1980s. 7 These organisations and spaces were the supporting structure of the so-called alternative and/or punk scene of Ljubljana.

Alternative scene

As early as the mid-1980s, punk became a key part of established youth culture, growing into a true multimedia cultural activity. 8 Aleš Erjavec and Marina Gržinić elaborate that art and culture that avoid ideological obstacles are those that typically break through. So, the ‘authentic’ art of the 1980s in Ljubljana is essentially an alternative art, a subculture that subverts established social schemes and patterns through the field of culture. In parallel with the assertion of the subculture and its consequences in politics and global society, the boundaries between art forms were broken and different genres connected: painting, theatre, music, and so on. The integrated works of art which were the product of this process of merging, also contained citation, appropriation and recycling. 9

Ljubljana with its alternative scene of the 1980s managed to withdraw from the margin and expose itself as a different choice, as the non-institutional formation and created a base for the formation of NGOs, the support of which were promised in the new alliance of the state. 10

In the third edition of Viks, the DIY publication published by ŠKUC-Forum (ŠKUC was at the time united with Forum, another important cultural organisation), Borčić and Gržinić wrote that the term ‘alternative art production’ within the Ljubljana subcultural scene primarily referred to the mechanisms of creation and operation of this production – its impossibility and inability to function as fine art, which was also conditioned by the inability to integrate into central cultural institutions, and spatial and financial conditions; together with the awareness of its actors towards these mechanisms. The ruling ideology and culture needed some alternative to testify to its democracy and pluralism, which in fact concealed the cynical attitude of the ruling culture, which needed to keep the ‘alternative’ on the margins. 11As Jasmina Založnik states, punk established a mass presence in the very centre of Ljubljana and one such important space for the subculture was definitely at Stari trg 21. To gain attention from the wider public, activists of the movement transformed clubs and galleries, private apartments and streets into multifunctional cultural and social spaces. 12

ŠKUC Gallery beginnings

Active since the early 1970s, ŠKUC acquired the spaces at Stari trg 21 (Ljubljana, Slovenia) later in 1978. The acquisition of the space started in the second half of the 1970s, when the then director Taja Vidmar-Brejc wished to present new trends and innovations in fine arts in Ljubljana’s city centre. She found that a bakery at Stari trg 21 was moving out and the premises were to be left empty. In an interview more than a decade later with Alenka Pirman, she recalls the acquisition period as full of bureaucratic obstacles, which she and her colleagues had to tackle to successfully open the gallery space in September of 1978. 13

The programme at the time was run without funds, and all work was voluntary. ŠKUC until this day consists of various sections that focus on visual arts, film, theatre, publishing, LGBT+ contents, and so on, and in the 1980s all these sections lived and breathed together at Stari trg 21, naturally, with varied desires, visions and interests. Vidmar-Brejc worked mostly with visual artists from her generation at the time. Due to conflicting visions for the space itself, she later decided that her collaborations with older generations of artists needed to continue in a different space altogether. Later, in 1983, she established Equrna Gallery, which in 1984 acquired a space not far from ŠKUC Gallery, remaining in the city centre, and functioning as a mix of an artists’ space and private gallery. 14

The new generation of editors and collaborators that also for a time worked together as artistic directors (artist Dušan Mandić, sociologist Marina Gržinić and art historian Barbara Borčić) at ŠKUC Gallery from 1981 introduced works by many authors from other Yugoslav centres as well, such as Zagreb and Belgrade conceptualists: Raša Todosijević, Dragan Papić, Working Community of Artists from Zagreb (Radna zajednica umjetnika iz Zagreba), Pino Ivančić, Vladimir Dodig Trokut, Tomislav Gotovac, Goran Đorđević, and so on. Insight into new art practices made it possible to establish a distance to both current and past artistic creativity. Gržinić and Borčić posed the question: Why, after so many years of such artistic creativity in other cultural centres, was it presented to the Slovenian public for the first time only in 1981 with the help of the ŠKUC Gallery? 15 With this came the acknowledgement of the incredibly forward-thinking projects at these cultural centres across the federation. After 1982, the extensive work of individuals at ŠKUC aided the opening of new possibilities for functioning in culture as an attempt to capture reality more comprehensively. Borčić and Gržinić argued that if art wants to be a part of reality / the street – it places itself in mass culture, rather than within a limited and dead art history. 16

Women as curators – Barbara Borčić and Marina Gržinić as artistic directors (1982–1985)

In an interview with Alenka Pirman in the early 1990s, Gržinić explained that she was not interested in what was happening in institutional galleries, her experiences coincided with the arrival of a new generation who thought differently and wanted something different. Working in the same space, things evolved organically and quickly. The scene essentially created the content of the space on Stari trg 21. 17

Založnik also addresses the fact that the Ljubljana alternative scene, which was the primal force of ‘punk and its metamorphoses’, as she names them, consisted mainly of students from Croatia, ‘representing inner migrants, who were also those who directly experienced the non-equality and violence of the non-favourable Slovenians’. 18 Born in Rijeka (Croatia), 19 Gržinić was one of those vocal students. As Gržinić herself emphasised in an interview with Tatjana Greif:

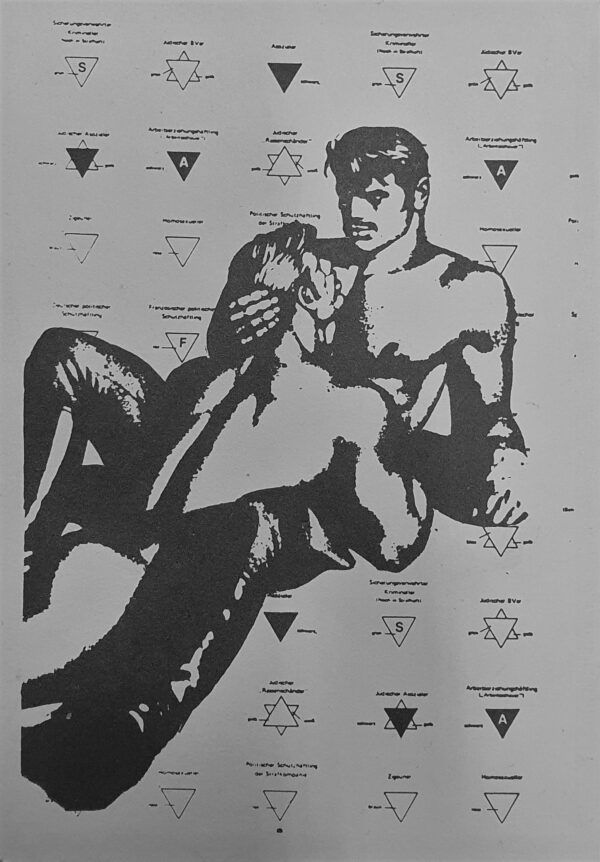

We understood that sexuality is the most important code in society and the only way to destroy communism is to make politics. This could be done only through the body, which could not be a heteronormative body. The only way to make this happen was by reference to aberrant sexual practices and their politics. This is what we knew from the theory; we knew that the state is presented and represented in its full totalitarian scope precisely through its suppression of the gay scene. 20

Gržinić and Borčić stated the following strategies implemented at ŠKUC: openness in the broadest sense, exploring the new, expressive possibilities of artistic language (regardless of age, position), 21 perverting the traditional system of reading, looking at a work of art as a system that sees the work of art itself as a useful object with market value, an object that aesthetically enlivens the environment or emphasises the content and is described in the categories of a ‘humanistic approach to man’ or ‘an inner richness of the expression of the author – artist’. 21

In the early 1990s, in a similar interview with Pirman, Borčić highlighted the possibility of the artist’s intervention in the field of

interpretation. She systematically represented the alternative artistic production from the Yugoslav space; an artistic practice that transcended the boundaries of traditionally conceived art. She also elaborated on the importance of the operation of many sections working in and from the same space. ŠKUC thus became a focus of ideas, concepts and planning of joint projects. The line between art and life, between audience and authors, was blurring, as almost everyone was involved in some way.

Many exhibitions started with a special event, such as a concert, blurring the borders between different artistic fields. It was ŠKUC who wanted to cross the line between gallery art and popular culture, which is supposed to belong on the streets and in clubs. They encouraged unconventional exhibitions, interventions in space, multimedia projects, performances, and so on, such that were not possible in other galleries. 22

Borčić continues this idea, later on, writing about self-organisation and self-representation as making a difference to the ruling ideology and cultural policy, and about fighting for the functioning and social recognition of alternative artistic and theoretical writing practices that addressed the social determinism of art, cultural stereotypes, myths and taboos, modern technology and the laws of the mass media. She also describes the establishment of autonomous conditions and spaces for operation, collective production modes and non-hierarchical and uncategorised production relations. This encouraged a shift from the production of objects to the concept of artistic practice as production of thought, ofmeaning. Collaboration and mutual support provided a kind of security. Later generations however strengthened this view of the communal work of the alternative and subcultural scene as a whole and valued it for its social strength. 23 Borčić explains this mode of work as follows:

Alternative production modes and relationships were based on the participation of different actors and the interweaving of artistic disciplines, and that is why this cultural/artistic production was interdisciplinary, intersectional, multimedia, transgenerational and often without definition or emphasis on authorship. 24

A clear product of such a collective approach to production, and one of the major projects with a firm social background under the directorship of Borčić and Gržinić is the initiative of the Magnus section at ŠKUC-Forum entitled Homosexuality and Culture (Homoseksualnost in kultura). It was first prepared by ŠKUC-Forum in April 1984. As the first public revaluation of gay culture in Yugoslavia, it was, as Erjavec and Gržinić write, also the first public attempt in an Eastern European country to differentiate

between homosexuality as a purely sexual orientation from gay culture, where this sexuality is realised through social factors, through specific language, fashion, art, consciousness and institutions. The project programme included movies, an exhibition, lectures, film screenings, and a gay disco. Only in the project’s aftermath did the producers realise how necessary this public display and the appearance of gay culture in Yugoslavia was. 25 This was also the beginning of the formation of the Magnus section at ŠKUC-Forum, which was the first gay organisation in a communist country and thus indirectly a lever for the gay community. In April 1985, the Lilit section also organised the first club meeting for women only, with the lesbian Lilit LL section following closely behind.

Women as artists – Meje kontrole št. 4 and Linije sile

Barbara Borčić and Marina Gržinić were not only active participants in the alternative scene, but were also designing posters, invitations, publications and producing interesting photographs, videos, and thinking about exhibitions as artworks in their entirety. Together with art historian and artist Aina Šmid, they prepared an exhibition in 1982 where they exhibited a series of punk-inspired photographs at ŠKUC. The show, whose ambience was determined by comprehensive sound and exhibition design, included photographs, slides, and conceptually selected music. 26

In 1982 Barbara Borčić, Marina Gržinić, Dušan Mandić and Aina Šmid also formed a group entitled Meje kontrole št. 4 (The Limits of Control No. 4). Together, they created two videos Icons of Glamour, Echoes of Death (Ikone glamurja, odmevi smrti, 1982) and The Threat of the Future (Grožnja prihodnosti, 1983), which were produced by ŠKUC-Forum.

Gržinić hails Icons of Glamour as one of the first works ‘from the communist world of the eighties to present and dramatise’, conceptually and politically, the institution of masculinity by introducing the drag king – a woman who publicly dresses and speaks like a man. Transgression of the binary social gender is achieved through the relationship between language and gender, and reveals the construction of gender through language. 27 Gržinić also mentions the performative role played by Dušan Mandić as the camera operator and simultaneous editor, yet she fails to mention the role played by Borčić. Gržinić and Šmid, as a twosome, continued creating queer positions, as they understood the non-heterosexual roles as a political stance that constantly re-questions life, work, possibilities of resistance and so on. 28

Another group representing the idea of mixing ‘the street’, popular culture, high art and including work by several female artists was the project called Linije sile (Lines of Force), initially consisting of Lidija Bernik, Tanja Lakovnik, Lela B. Njatin, Mojca Pungerčar and Aina Šmid. Their fashion production and shows were based on the punk starting points of the 1980s. 29 In December 1983, Linije sile staged a fashion show at ŠKUC as a performance of heterogeneous images. They created a spectacle, not only showing the latest sartorial creations and fashion accessories. According to Gržinić, this project marks the beginning of the media problematisation of fashion as a relevant field, which is no longer just an accompanying element of other media – music, video, film, and so on. Linije sile functioned precisely as a form of multimedia glorification of the consumer spectacle, which also proved to be a convincing model of mass entertainment. This fusion of entertainment and culture came as a truly genuine spectacle into gallery spaces. 30

Aina Šmid, in the first edition of Viks, explained that the term ‘fashion’ was generally understood as the way of dressing, behaving, and so on, in both a broader and narrower sense. It did not focus on fashion within the definitions and methodology constituted, if any, by the sociology of fashion, and within the stylistic categories established by its history. She addressed fashion as the bearer of class affiliation and, after industrial development, marked it as one that erases sharp indicators of affiliation to individual social classes and strata. Boutique creations were limited only to representatives of the wealthier elite, through so-called ‘high fashion’. Although some clues about class affiliation and personality can be discerned from an individual’s clothing, it is nevertheless mainly based on copying. 31 The fashion industry, therefore, suggests a type of personality, an ‘image’, which the individual should adopt, thus creating a personality market. At the same time, Šmid understands dressing as a possible manifestation of compensatory behaviour, the possibility of representing ‘what a personality would like to be’. 32 She concludes with Dick Hebdige’s finding that the image and fashion of subculture function as a resistance to the hierarchy of values imposed by society. At the same time, this resistance can be adapted since the media of mass culture ‘record’ the deviance of the subculture and place it within the dominant ideology. She concludes with the thought:

Subculture and fashion as one of the accompanying derivatives are […] determined by the conditions of the consumer economy of the existing society and ‘forced’ to adapt to the ruling ideology. 33

Conclusion

The acquisition of the permanent premises of the ŠKUC in 1978, at Stari trg 21 in Ljubljana, enabled the continuous presentation and execution of the programmes of individual sections of ŠKUC most importantly in collaboration with each other. Despite the saturation of the common space with art, theatre, dance and other programmes, this concentration of activities and events in a permanent place in the centre of Ljubljana was crucial for the expansion of alternative activities and their establishment in the Slovenian cultural space. In the history of ŠKUC, there have been several women in decision-making places who have crucially contributed to its continuous representation of visual art, as well as active entanglement in current social issues. The work of Barbara Borčić and Marina Gržinić as artistic directors in the 1980s, their involvement in the alternative scene and with numerous collaborators from ŠKUC, in various media, as well as local and international organisations, created and continuously addressed the importance of culture where spatial collectivity and collaborative projects were in the foreground. Brimming with creative and critical thought, addressing social issues and creating projects ahead of their times, ŠKUC was a hub of incredibly advanced content and criticality which might be attributed to the cooperation between Barbara Borčić and Marina Gržinić, as well as the overall connectedness of the entire alternative scene.

Acknowledgements for transmitting and assisting with information: Barbara Borčić, Joško Pajer and Slađana Petrović Varagić.

Bibliography

Borčić, Barbara, ‘Večmedijski obrat – dvojni pogled’, in Osemdeseta. Slovenija in Jugoslavija skozi prizmo dogodkov, razstav in diskurzov, ed. by Igor Španjol (Ljubljana: Moderna galerija, 2018), pp. 61–67

Borčić, Barbara, ed., Videodokument. Video umetnost v Slovenskem prostoru 1969–1998, dokumentacija / Video Art in Slovenia 1969–1998, Documentation (Ljubljana: Open Society Institute – Slovenia, 1999)

Borčić, Barbara and Marina Gržinić, ‘novi projekti v galeriji ŠKUC’, Tribuna, 10 November 1982, 11]

Borčić, Barbara and Marina Gržinić, ‘Slikati eno, da bi se odslikalo drugo’, Viks, 3, no. 3 (1985), 30–32

Erjavec, Aleš and Marina Gržinić, Ljubljana, Ljubljana. Osemdeseta leta v umetnosti in kulturi (Ljubljana: Založba Mladinske knjige, 1991)

Greif, Tatjana, ‘Obscenost krščanskega diskurza je monstruozna – Intervju z Marino Gržinić’, Časopis za kritiko znanosti, 37, no. 237 (2009), 145–155

Gržinić, Marina, Galerija ŠKUC Ljubljana / The ŠKUC Gallery: 1978–1987 (Ljubljana: ŠKUC, 1988)

Gržinić, Marina, ‘The Video, Film, and Interactive Multimedia Art of Marina Gržinić and Aina Šmid, 1982–2008’, in New-media Technology, Science, and Politics: The Video Art of Marina Gržinić and Aina Šmid, ed. by Marina Gržinić and Tanja Velagić (Vienna: Erhard Löcker, 2008), pp. 39–158

Gržinić, Marina, ‘Uvodnik’, Viks 1, no. 1 (1983), 4

Gržinić, Marina and Barbara Borčić, ‘Likovna produkcija v ŠKUCU’, Tribuna, May/June 1982, unpag

Gržinić, Marina and Barbara Borčić, ‘ŠKUC in njegova likovna produkcija’, Tribuna, 1 October 1982, 5

Malešič, Martina and Asta Vrečko, ‘Novi prostori, nove podobe’, in Osemdeseta. Slovenija in Jugoslavija skozi prizmo dogodkov, razstav in diskurzov, ed. by Igor Španjol (Ljubljana: Moderna galerija, 2018), pp. 45–59

Pirjevec, Jože, Jugoslavija 1918–1992. Nastanek, razvoj ter razpad Karadjordjeviće in Titove Jugoslavije (Koper: Lipa, 1995)

Pirman, Alenka, ‘Artistic Directors of the ŠKUC Gallery, 1978–1996’, in Somewhere Else: Weimar 1999, ed. by Gregor Podnar (Ljubljana: Galerija ŠKUC, 1999), pp. 8–23

Repe, Božo, ‘Oris družbenih razmer v Sloveniji in v Jugoslaviji v osemdesetih letih 20. stoletja’, in Zdenko Čepič et al., Prikrita modra mreža. Organi za notranje zadeve republike Slovenije v projektu MSNZ leta 1990 (Ljubljana: Inštitut za novejšo zgodovino, 2010), pp. 20–41

Repe, Božo, ‘Vloga slovenskega punka pri širjenju svobode v samoupravnem socializmu sedemdesetih let’, in Punk je bil prej. 25 let punka pod Slovenci, ed. by Peter Lovšin, Peter Mlakar and Igor Vidmar (Ljubljana: Cankarjeva založba in ROPOT, 2002), pp. 54–65

Šmid, Aina, ‘K fenomenu mode v funkciji množične culture’, Viks, 1, no. 1 (1983), 17–19

Zabel, Igor, ‘Slovenska umetnost 1975–1985: koncepti in konteksti’, in Do roba in naprej. Slovenska umetnost 1975–1985, ed. by Igor Španjol and Igor Zabel (Ljubljana: Moderna galerija, 2003), pp. 10–26

Založnik, Jasmina, ‘Punk as a Strategy for Body Politicisation in the Ljubljana Alternative Scene of the 1980s’, AM Journal of Art and Media Studies, 14 (2017), 145–156 DOI: <10.25038/am.v0i14.217>

- Igor Zabel, ‘Slovenska umetnost 1975–1985: koncepti in konteksti’, in Do roba in naprej. Slovenska umetnost 1975–1985, ed. by Igor Španjol and Igor Zabel (Ljubljana: Moderna galerija, 2003), pp. 10–26 (p. 10). ↩︎

- Božo Repe, ‘Oris družbenih razmer v Sloveniji in v Jugoslaviji v osemdesetih letih 20. stoletja’, in Zdenko Čepič et al., Prikrita modra mreža. Organi za notranje zadeve republike Slovenije v projektu MSNZ leta 1990 (Ljubljana: Inštitut za novejšo zgodovino, 2010), pp. 20–41 (pp. 20–22). ↩︎

- Ibidem, pp. 23–24. ↩︎

- There were 699 strikes in Yugoslavia in 1985, twice as many as in 1984 and four times as many as in 1983. See: Jože Pirjevec, Jugoslavija 1918–1992. Nastanek, razvoj ter razpad Karadjordjeviće in Titove Jugoslavije (Koper: Lipa, 1995), p. 379 ↩︎

- Ibidem, p. 369. ↩︎

- Božo Repe, ‘Oris družbenih razmer v Sloveniji in v Jugoslaviji v osemdesetih letih

20. stoletja’, p. 26 ↩︎ - Božo Repe, ‘Vloga slovenskega punka pri širjenju svobode v samoupravnem socializmu sedemdesetih let’, in Punk je bil prej. 25 let punka pod Slovenci, ed. by Peter Lovšin, Peter Mlakar and Igor Vidmar (Ljubljana: Cankarjeva založba in ROPOT, 2002), pp. 54–65 (p. 54). ↩︎

- Božo Repe, ‘Oris družbenih razmer v Sloveniji in v Jugoslaviji v osemdesetih letih 20. stoletja’, p. 25. ↩︎

- Aleš Erjavec and Marina Gržinić, Ljubljana, Ljubljana. Osemdeseta leta v umetnosti in kulturi (Ljubljana: Založba Mladinska knjiga, 1991), p. 18. ↩︎

- Jasmina Založnik, ‘Punk as a Strategy for Body Politicisation in the Ljubljana Alternative Scene of the 1980s’, AM Journal of Art and Media Studies, 14 (2017), 145–156 (p. 154), DOI: <10.25038/am.v0i14.217 ↩︎

- Barbara Borčić and Marina Gržinić, ‘Slikati eno, da bi se odslikalo drugo’, Viks, 3, no. 3 (1985), 30–32 (p. 31) ↩︎

- Jasmina Založnik, ‘Punk as a Strategy for Body Politicisation in the Ljubljana Alternative Scene of the 1980s’, p. 146. ↩︎

- Alenka Pirman, ‘Artistic Directors of the ŠKUC Gallery, 1978–1996’, in Somewhere Else: Weimar 1999, ed. by Gregor Podnar (Ljubljana: ŠKUC Gallery, 1999), pp. 8–23 (pp. 9–10). ↩︎

- Martina Malešič and Asta Vrečko, ‘Novi prostori, nove podobe’, in Osemdeseta. Slovenija in Jugoslavija skozi prizmo dogodkov, razstav in diskurzov, ed. by Igor Španjol (Ljubljana: Moderna galerija, 2018), pp. 45–59 (p. 59). ↩︎

- Marina Gržinić and Barbara Borčić, ‘Likovna produkcija v ŠKUCU’, Tribuna, May/June, 1982, unpag. ↩︎

- Barbara Borčić and Marina Gržinić, ‘novi projekti v galeriji ŠKUC’, Tribuna, 10 November 1982, 11. ↩︎

- Alenka Pirman, ‘Artistic Directors of the ŠKUC Gallery, 1978–1996’, p. 13. ↩︎

- Jasmina Založnik, ‘Punk as a Strategy for Body Politicisation in the Ljubljana Alternative Scene of the 1980s’, p. 151 ↩︎

- Alenka Pirman, ‘Artistic Directors of the ŠKUC Gallery, 1978–1996’, p. 15. ↩︎

- Tatjana Greif, ‘Obscenost krščanskega diskurza je monstruozna – Intervju z Marino Gržinić’, Časopis za kritiko znanosti, 37, no. 237 (2009),

145–155 (p. 146). ↩︎ - Marina Gržinić and Barbara Borčić, ‘Likovna produkcija v ŠKUCU’ ↩︎

- Alenka Pirman, ‘Artistic Directors of the ŠKUC Gallery, 1978–1996’, pp. 16–17 ↩︎

- Barbara Borčić, ‘Večmedijski obrat – dvojni pogled’, in Osemdeseta, ed. by Igor Španjol, pp. 61–67 (p. 64). ↩︎

- Ibidem. ↩︎

- Aleš Erjavec and Marina Gržinić, Ljubljana, p. 49. ↩︎

- Marina Gržinić, Galerija ŠKUC Ljubljana / The ŠKUC Gallery: 1978–1987 (Ljubljana: ŠKUC, 1988), p. 10. ↩︎

- Marina Gržinić, ‘The Video, Film, and Interactive Multimedia Art of Marina Gržinić and Aina Šmid, 1982–2008’, in New-media Technology, Science, and Politics: The Video Art of Marina Gržinić and Aina Šmid, ed. by Marina Gržinić and Tanja Velagić (Vienna: Erhard Löcker, 2008), pp. 39–158 (p. 48). ↩︎

- Ibidem. ↩︎

- Aleš Erjavec and Marina Gržinić, Ljubljana, p. 46 ↩︎

- Marina Gržinić, Galerija ŠKUC Ljubljana 1978–1987, pp. 175–176. ↩︎

- Aina Šmid, ‘K fenomenu mode v funkciji množične culture’, Viks, 1, no. 1 (1983), 17–19 (p. 17). ↩︎

- Ibidem. ↩︎

- Ibidem, p. 19. ↩︎

Tia Čiček

Tia Čiček has an MA in art history from the Faculty of Arts at the University of Ljubljana (Slovenia), where her master’s thesis included various archival works and was entitled The Professional Work of Ana Schiffrer in the Carniolan Provincial Museum (2019). For the last few years, she has worked as a curator and producer of contemporary art in various spaces such as the Centre for Urban Culture Kino Šiška and DobraVaga, and she is the current artistic director of Škuc Gallery (all in Ljubljana). In 2018 she attended a course at the International Summer Academy of Fine Arts in Salzburg led by Ruth Noack and Grace Samboh entitled Thinking with Works of Art, and she recently finished the two-year curatorial programme at the World of Art School for Curatorial Practices and Critical Writing (SCCA, Ljubljana).