Tytuł

Hideouts The Architecture of Survival and its Conceptual Constellation: from Awkward Objects to Counter-monuments

https://www.doi.org/10.48285/ASPWAW.29564158.MCE.2022.8.8

https://miejsce.asp.waw.pl/memory-and-art-in-1-1-scale-from-aesthetic-forensics-to-counter-monuments/

DOI

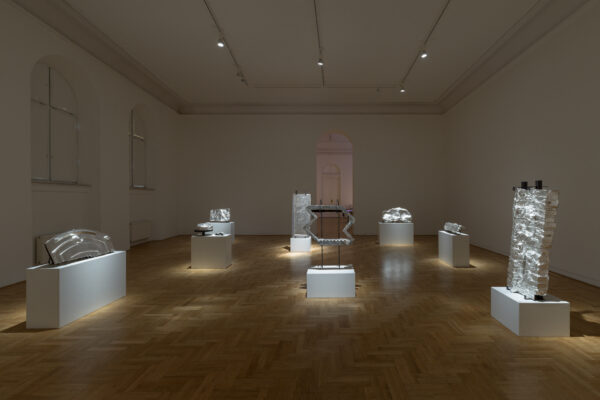

1. Exhibition

This visual essay presents the conceptual constellation of the ‘Hideouts. The Architecture of Survival’ exhibition. The discussion of this specific case offers some insights into the methods of artistic research located at the intersection of the ever-expanding fields of contemporary art and the studies of memory, history and the Holocaust. The main point of reference here is the exhibition to which we all contributed as artists, curators and researchers. This artistic tribute to the architecture of survival – the hiding places, including tree hollows, wardrobes, urban sewers, caves and empty graves that Jews (and/or their allies) adapted into temporary shelters and used during World War II – consisted of casts of nine hiding places from around Poland and Ukraine, gilded in true silver to create reflective, mirror-like surfaces. The exhibition of sculptural forms was accompanied by a narrative section presenting the results of interdisciplinary research carried out by a team of artists, architects, anthropologists, historians, archaeologists and urban explorers. The exhibition was shown at the Zachęta National Gallery of Art in Warsaw (April – July 2022) and the TRAFO Center for Contemporary Art in Szczecin (August – November 2022), garnering popular acclaim and extensive media coverage, and drawing the attention of contemporary art, artistic research, memory studies and the Jewish heritage scholars and practitioners. In order to convey the multidimensional character of the preparatory research, but also to maintain consistency with the artistically charged and intellectually potent content of the exhibition, this visual essay is composed of two juxtaposed tracks of images and words.

2. Mirrors and concealment

Sculpture - fragment of a hiding place - entrance to the hideout in Zhovkva/Żółkiew, image by Jakub Celej, 2022

By artistically modifying the models of the hiding places – which by definition must remain invisible to the unsanctioned eye – the exhibition plays with visibility as the essential architectural property of hideouts. In order to serve as hideouts, the architectural or natural environments had to remain visually unchanged: a tree had to remain looking like a tree, a floor like a regular floor and a wardrobe like a normal piece of furniture. Meanwhile, their architectural function changed drastically: a tree hollow became a temporary shelter, a cellar turned into a living space for an entire family, a cabinet was transformed into a place of hiding. The artistic forms created for the exhibition seek to emphasize the paradoxical nature of this architecture.

Covered with polished silver, the architectural casts of hideouts acquired reflective, mirror-like surfaces. Mirrors do not have any visual substance of their own; they reflect images of their surroundings and tend to blend with them. Believed to have special properties, mirrors have been used throughout centuries in magical rituals: helping to see what would otherwise remain unseen. Hence, mirror-like sculptures are apt tools of architectural hauntology. Here they conjure the specters of the invisible Holocaust-era architecture, which despite its modest form and lack of visibility stands as an important historical witness, unearthed at application of a set of artistic procedures and research methodologies.

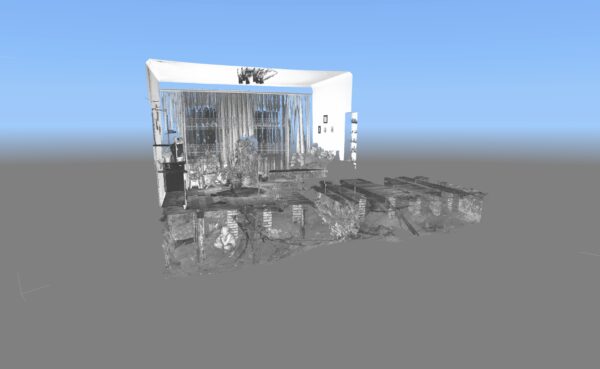

3. Vernacular architecture of survival

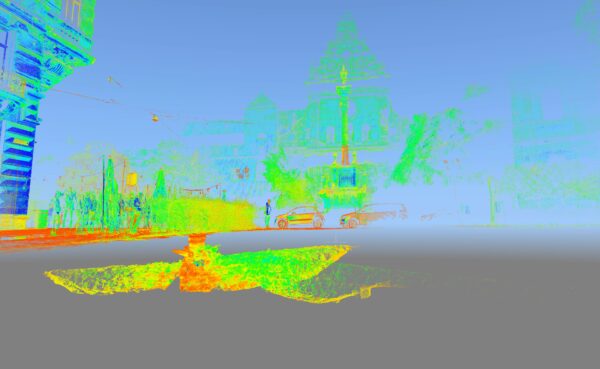

3D scans of parts of the urban sewage system in Lviv, image by Przemysław Kluźniak (ArchiTube), 2022

The exhibition reflects on fundamental problems of architecture and social coexistence, such as the relationship between form and function or the design and use of space. The hiding places were often created ad hoc, out of the need of the moment, in places originally unsuitable for them, by amateurs without prior experience in construction or planning. They are a testament to the architectural creativity of people in hiding working to secure their basic survival — often for an extended period of time — with minimal resources and unable to radically alter the space available to them, while remaining completely inconspicuous. A cellar, a cave or a section of a sewage system were turned into full-fledged housing for entire families: food had to be cooked, sleeping quarters arranged, waste disposed. In some cases such hideouts served for as long as two years. Other hideouts offered only temporary shelter, as Jews moved from one hideout to another, in order to ensure own survival. The acts of finding them, adapting them for use and using them should be seen for what they were: modes of everyday resistance. The architecture of these hideouts reflect the agency of the people in hiding, testifying to their ingenuity and vernacular architectural talent.

4. Awkward objects

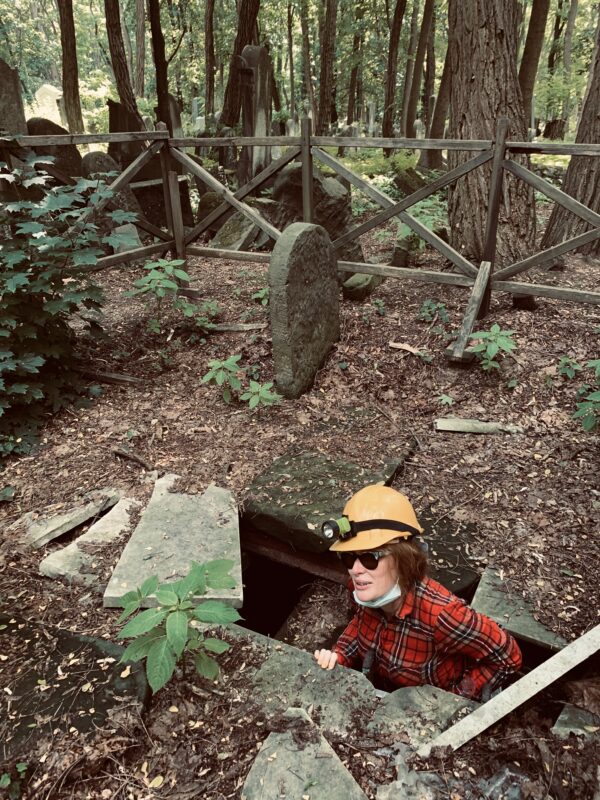

The remnant Jewish hiding places of World War II surviving to this day in their original material form can be seen as awkward structures. The theoretical concept of an ‘awkward object’ tries to deal with objects that linger at the margins of disciplines, typically beyond the academically delineated fields of interest. The materiality of hideouts tends to be overlooked by historians (who give priority to first-hand accounts) and architects (for whom these are not architectural enough). Viewed largely as not monumental enough, hideouts have dwelled on the margins of the contemporary culture of commemoration. Following Mary Douglas’s definition of an awkward object, the preserved Jewish hideouts can be interpreted as ‘matter out of place:’ they are provisional ‘homes’ or shelters with some everyday objects located in caves, sewage systems, inside a hollow tree trunk or an empty grave. Their relationship to time is also awkward: some of these temporary, provisional structures, built to last for days, weeks, maybe months, survive to this day, escaping erosion and changes in the urban and rural landscape. In some cases, they also surface awkwardly late, being located or discovered after decades of remaining hidden in plain sight – as in the case of a wardrobe in Huta Zaborowska, central Poland, identified in 2020 as a hiding place of a Jewish child in 1943. Located in obscure and hard to reach places, these hiding places pose a challenge to those wanting to study them; they force researchers to spend time in awkward positions (e.g. crawling through underground passages or balancing on a scissors lift), often in singular company (e.g. of dendrologists, dendrochronologists, speleologists, etc.) and to reach over disciplinary and methodological boundaries.

5. A wardrobe

In 2020, the POLIN Museum of the History of Polish Jews received a wardrobe found in a country house in the village of Huta Zaborowska (near Gostynin) in Poland. Inside the furniture piece, there were handwritings and drawings, including information that the wardrobe served as a hiding place between February 21st and April 25th, 1943. The sketches discovered on the boards inside the wardrobe were made in pencil, by applying varying degrees of pressure. These are accumulated towards the left and in the centre. Since the inscriptions (figures and writing) were made at different angles, the author(s) presumably adopted different body positions while creating them. It is possible that the wardrobe was positioned horizontally for some time, so that the person in hiding could lie on a soft bedding (a quilt, clothing or mattress). The inscriptions are not arranged in a single line, and their distribution points to changes in the wardrobe’s position. Most of them are well preserved, with only one (depicting a sexual act) partially erased, likely by its maker. The preliminary research suggests that the inscriptions inside the wardrobe are authentic historical evidence dating back to World War II times. Further research of the object continues.

6. Post-artistic practices in the expanded field

Aga Szreder and Rafał Żwirek making a silicone mould of the tree in Wiśniowa, image by Natalia Romik, 2021

The research of awkward objects requires new interdisciplinary toolboxes. Alongside the established historical, archival and architectural procedures, this includes the artistic methodologies embedded in the expanded field of art, which traverse the long-established disciplinary distinctions, such as that between art and science. To explain this process of cross-disciplinary innovation, we refer to a concept of ‘post-artistic age,’ proposed by a Polish theoretician of contemporary art Jerzy Ludwiński in his essay Art in the post-artistic age (1971). He discussed in it the processes of diffusion, deskilling and dematerialization that unfolded in the 1960s and in result of which art has lost its distinctive formal characteristics; in Ludwiński’s words: ‘Perhaps, even today, we do not deal with art. We might have overlooked the moment when it transformed itself into something else, something which we cannot yet name. It is certain, however, that what we are dealing with offers greater possibilities.’ His essay covers a plethora of new post-artistic practices that emerged since 1960s: post-conceptual, socially engaged, relational, useful and research-based art. Importantly, it also includes an array of practices located at the intersections of art and science, art and history as well as art and memory studies. Research conducted in the post-artistic age does not abandon art specific spaces and conventions altogether. For example, the Hideouts exhibition was located in the Polish state’s preeminent national gallery of art, but we were free to move beyond the field of art and create links with other genres and disciplines. In this vein, the exhibition offered space for aesthetic contemplation as much as for the analysis of a scientifically grounded narrative on the architecture of survival.

7. Artistic research

Natalia Romik during her research in the hideout at the Jewish Cemetery in Warsaw, image by Rafał Żwirek, 2021

Thus art is hybridized with architecture, archival research, archeological surveys and ethnography. The objects begotten through such processes are not only expressions of their author’s unique vision; they are also means of intersubjective research and communication: telling us something about the world we cohabit with other people in a way that is not only important, but also truthful. This art results from cross-, extra- and inter-disciplinary collaboration with experts who employ their varied methodologies to generate knowledge about reality. In the case of Hideouts, this interdisciplinary collaborative team included archaeologists, historians, filmmakers, ethnographers, dendrochronologists and many others. On the other hand, the artistic or aesthetic forms of the hideout effigies communicate something that a regular academic paper cannot: the thingness, crudeness and the undeniable materiality of their architecture. Instead of reconciling all, the artistic forms – constituted not only in their glittering surfaces, but also in their dark and earthy obverse – point to complex and conflicting relationships between concealment and visibility, between the dramatic experience of being-in-hiding and the ocular sensations of the viewers, and between the deficiency of architectural resources and the agency of the people who employed them.

8. Field coalitions

Interdisciplinary projects are not implemented in the seclusion of an artist’s studio; field research is the stuff they are made of. In order for such projects to succeed, one needs to convene a broad coalition of institutions and individuals active in various disciplines and representing various walks of life. As an example, the alliance which came into being in order to develop one part of our exhibition, namely the Józef Oak, included: a local cultural center, a school in Wiśniowa, a studio where the casts were made, a workshop where silver leaf was applied to these, the archive of the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum in Washington D.C., the laboratory in which the dendrochronologists worked and finally the Zachęta gallery exhibition space. Such an arrangement does not lend itself to control as easily as an artist’s studio or a historical archive – for better or worse. One needs to account for changes in weather patterns, closed borders and other disruptions; at the same time, such an arrangement creates space for unexpected encounters that at times lead to major breakthroughs. When making the mold of the Jozef oak tree, we were approached by a pair of local researchers who directed us to Jewish brothers who hid inside the tree some eighty years earlier. Only by visiting Lviv were we able to meet the urban explorers who had mapped the sections of the city sewer system in which some Jewish families survived the war. And just because we ventured down to the Vertreba Cave near Ternopil, we spotted the word ’Hashomer‘ (Hebrew: a guardian) carved on its wall, possibly by the Jews who sojourned there during the Holocaust. Art allows us to make connections, but we need coalitions to further them.

9. Art in 1:1 scale

The core of the exhibition revolved around nine sculptural models of Jewish hideouts. These were full-scale casts of substantial sections of currently existing hideouts. In the contemporary theory of art, the notion of ‘one-to-one scale’ is imbued with a very specific meaning that expands from the physical to conceptual, and from the realm of aesthetics to the domain of use. The concept was coined by Stephen Wright to discuss art-related projects that become part and parcel of social practice, hardly distinguishable from other similar social practices, and yet still covered in conceptual films and imbued with artistic meanings. In his treatise ‘Towards a lexicon of usership,’ he posits that art on one-to-one scale is both a conceptual proposition and realization of aesthetic potential in social practice. For example, an artist-initiated bakery can be both a conceptual piece of art and a place to bake bread. At first glance, the same cannot be said about Hideouts. By design, the hiding places presented in it cannot be mistaken for actual hiding places; there is also no intention to ‘move them back’ to their original locations or to use them. But then – if we think differently about this notion of scale and use – the Hideouts project is not a mere exhibition. It is a warning sign or a red flag shouting ‘never again,’ emphasizing once more that we need to do everything in our power so as not to repeat the historical tragedies that necessitated the making of such hideouts in the first place. The casts serve as counter-monuments and devices of social memory which transform the gallery into a space for discussion and negotiation of this troubled yet still vivid history.

10. Forensic aesthetics

Coined by Eyal Weizman, ‘forensic aesthetics’ is a concept that has informed the research practice of Forensic Architecture, a research cluster based in London. Weizman discusses architectural forensics in the context of actual court proceedings, claiming that it creates evidence valid for the court room, supporting investigations into the violations of human rights, war crimes and other abuses. To explain these activities, Weizman refers to an ancient Greek concept of prosopopeia, a rhetorical device that endows mute objects with speech. Even though we also employ methods of architectural and aesthetical forensics (to let the otherwise silent and hidden architecture speak), their mode of activation is different. The focus here is on processes of negotiating memory rather than on creating evidence for court proceedings. There are no court rooms and neither are there tribunals, unless we think about them metaphorically, as public tribunals of memory and forgetting. In the contemporary public sphere, afflicted with short attention spans, we have to compete for the flickers of attention with other transitory propositions floated on social and mass media, and need to counter the operations of state apparatuses that conserve politically charged visions of history. The important difference is that there are no judges and no proceedings in the courts of history; they last for ages (literally), require patience and negotiation, involve unspecified number of both human and nonhuman agents, spanning through spatiotemporal dis-continuum. Operation in this expanded and messy space of public memory requires aesthetic subtlety. One does not need to objectify history as evidence, but rather to tend to memory – to cultivate it as if it were a delicate plant. When dealing with awkward objects, such as hideouts, one shuns from the persuasive modes of exhibition-making, characterized by slick aesthetics and didacticism. In contrast, hideouts dwell in the space of reflection; the subject matter requires distance, where complexities can be embraced and contradictions contemplated. Even though the Hideouts exhibition remains nuanced, it does not relativize, offering an emphatic testimony from a quest for historical truth, a logbook of the challenging mission to commemorate.

11. Material witnesses

Objects found in the sewage system (torch, glass bottle, Easter lamb) in the Chiger family shelter, private collection of Anna Tychka, image by Daniel Chrobak, 2022

Matter can register violent events and archive interactions that can be later decoded to provide data and information about acts of violence. Wartime Jewish hideouts can be treated as material witnesses; their structure, construction, the traces of the tools used to build them (often small, everyday objects such as ‘a blunt chisel or a kitchen hammer’) left on surfaces and materials offer researchers detailed insights into the process of their creation and usage. Susan Schuppli stresses the importance of exploring the evidential role of matter as both registering external events and exposing the practices and procedures that enable matter to bear witness. When approached with an interdisciplinary toolbox, the preserved Jewish hideouts can act as material witnesses and offer rare testimonies that have perhaps been overlooked and deserve attention, as the ‘the era of the (human) witness’ is coming to an end.

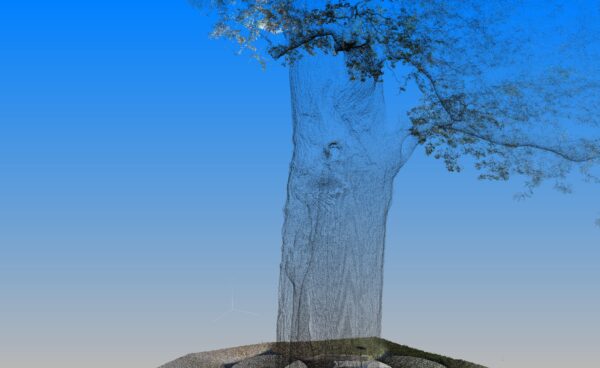

12. A tree

The more than 650-year-old Józef oak grows in a park on the grounds of the Wiśniowa Manor in the Podkarpackie Region of Poland. The local community retains the memory that it was a wartime hiding place for two Jewish brothers, which is also confirmed by a post-war account by a journalist named Julian Pelc. The Józef oak is a living chimney tree, hollow inside nearly through its entire height. During the war, there was an entrance to its interior, at a level accessible to people. Today, that entrance is overgrown and only a crevice remains, barely large enough to peer inside. We found the hollow trunk to still hold inside a dozen wooden steps and metal brackets. For David and Paul Denholz, who came from nearby Frysztak, this was probably one of their several hiding places. After escaping in 1942 from the KL Płaszów camp in Kraków, they hid in the surrounding forests, fields and farms. Some of their former neighbors came to their aid, others posed a mortal threat. They were the only members of their family to survive the war, and after it ended, they both settled in the United States. At the exhibition in Zachęta, the silvered sculpture of the tree held a place of honor – at its very entrance. It told the unique history of the Jewish brothers, as witnessed by the ancient oak, whose testimony was transposed into the language of aesthetic forms.

13. Translations

The process of silver-plating the sculptures in the workshop of Piotr Pelc, image by Ada Gruszka, 2021

Our one-to-one hideout casts were conceived as means of translating the muted speech of material witnesses into the language of aesthetic forms – no less sophisticated, but potentially accessible to human audiences. Here aesthetics become not only a mode of presentation, but also of cognition. The process of translation between objects and humans is facilitated by a multiplicity of different methods; artistic forms are combined with archive records, reports, maps, 3D scans, archeological findings, all the while providing a suitable context for different modalities of experience. Sculptures are given space to reverberate aesthetically, documents are narrated in displays evoking museums of natural history. This entire hybrid assemblage serves as an interface for a series of object-to-human translations, counter-monuments and memory devices.

14. Reflections

Sculpture fragment of a hiding place form a hideout in the convent of the Immaculate Conception Sisters in Jarosław, image by Jakub Celej, 2021

The hideout casts covered in pure silver leaf somehow confront us with our own hazy reflections, implicating the viewers as voyeurs of otherwise concealed architecture. The reflective surfaces of the sculptures create a translucent and elusive yet impenetrable barrier between the experience of the people in hiding and the experience of the people who – decades later – watch the material traces of that original experience. There is no way out of this fundamental contradiction, we are faced with it the moment we see our own reflections mirrored in the lustrous surfaces of the sculptural casts of underground corridors or caves, where people hid for a year or two, in utter darkness. On the other hand, these mirrors have both allure and function; they serve as devices of memory and interfaces for object-to-human translation, employed in the task of commemoration.

15. Vernacular memory and its stewardship

Social modes of remembering can be seen as multilayered. Following Roma Sendyka’s suggestions, we can distinguish between the official or institutionalized memory and the vernacular memory. ‘Closest to the ground,’ this latter layer often goes unheard and remains hidden from public view. Vernacular memory often develops independently of official narratives, on a local, communal level. It does not rely on the public thus endorsed forms of remembering (monuments, plaques, codified memorial gestures); instead it favors unspectacular practices, usually unnoticed by the uninformed observer. Such vernacular memory has also developed in relation to the hideouts of the Holocaust era. Their ‘guardians’ and ‘stewards’ often perform ‘small’ commemorative practices. There is a small hole in one wall of a hideout preserved under a private house in Zhovkva/Żółkiew– most probably serving as an airflow duct. Clara Kramer recollects in her diary that when she hid there with 18 other people, she often smelled the scent of the marigolds growing by the house wafting to the inside of the hideout through that hole. Iryna Dobrokhodskaya, now living in the house and well aware of Clara Kramer’s account, continues to plant the same flowers in the same place today.

16. Counter-monuments

The hideout sculptures serve as counter-monuments, erected to honor the architectural creativity and the will to survive of their builders. Focusing on daily struggles and bottom-up solidarities, these forms deconstruct inflated mythologies reinforced by public monuments that typically laud war leaders, amplify national identities or signify martyrdom of entire peoples. Here, the commemoration is spelled in the singular, it is history with an individual face, told in nitty-gritty detail by material witnesses themselves. The extremely modest and poor architecture of the hideouts cannot and should not be seen through rose-tinted spectacles. The exhibition commemorates the unique histories of survivors who reused stinky, damp, dirty and dark places as their own spaces of refuge, while celebrating their creativity and everyday heroism. This contrast between the undeniably distressing circumstances and the laudable ingenuity of people in hiding is highlighted by the use of gilding techniques, typically reserved for sacral architecture – to adorn altars or figures of saints. Here, the same technique is used to venerate the architectural traces of the everyday heroism of people who built and used the life-saving hideouts, and to amplify the murmurs of memory audible only in a chorus, to add new tones to a tune hummed by many.

Natalia Romik

Natalia Romik is a graduate in political science, practitioner of architecture, designer, artist, member of the Association of Polish Architects. In 2018 she was awarded a PhD at the Bartlett School of Architecture, University College London, for a thesis entitled “Post-Jewish Architecture of Memory within Former Eastern European Shtetls.” Currently Dr Romik holds a scholarship from the Gerda Henkel Stiftung program. In her practice, she combines academic research with methods of contemporary art and architecture, realizing numerous projects such as: “Predator” and “What Makes You Horny and Itchy in Architecture?” performances for the “PARADE. Critical Practice” festival in London; “Nomadic Shtetl Archive,” “Open Anti-fascist Studio” and “Dream Catcher—Mobile Sauna,” carried out in the course of two editions of the Roskilde Festival in Denmark. Dr Romik has been awarded numerous grants, including that of the London Arts and Humanities Partnership for her doctoral studies, and the Scholarship of the Minister of Culture and National Heritage of Poland for the Jewish Architecture of (Non)Memory in Silesia project. Between 2007 and 2014, she cooperated with the Nizio Design studio as, amongst other things: Consultant for the core exhibition design of the “19th Century Gallery” in the POLIN Museum of the History of Polish Jews; and co-author of the restoration of the 18th century synagogue in Chmielnik. In 2018, she designed and co-curated (together with Justyna Koszarska-Szulc), Estranged: March ’68 and Its Aftermath exhibition (POLIN Museum of the History of Polish Jews, Warsaw 2018). Dr Romik is a member of the SENNA architecture collective, which designed, among other things, the core exhibition of the 19th century neo-Gothic Jewish Pre-Burial House in Gliwice, titled “House of Memory of Upper Silesian Jews.”

Kuba Szreder

Kuba Szreder is a lecturer at the department of art theory at the Academy of Fine Arts in Warsaw. Graduate of sociology at the Jagiellonian University (Krakow), he received PhD from the Loughborough University School of the Arts. He combines practice-based research with curating interdisciplinary projects and political engagement. He has worked with many artistic institutions and collectives in Europe. In 2009 he co-initiated Free / Slow University of Warsaw, with which he completed several inquiries into the political economy of contemporary artistic production, such as Joy Forever. Political Economy of Social Creativity (2011) and Art Factory. Division of labor and distribution of resources in the field of contemporary art in Poland (2014). In 2010 he started to cooperate with Critical Practice, a London-based research cluster, with which he conducted several research projects about the modes of being in public (2010-2011), and the social process of evaluation (2012-2016). Since 2012 he has worked with the Citizens Forum for Contemporary Art in Poland, with which he has campaigned for the betterment of conditions of work in the sector of contemporary art. In 2018 together with Kathrin Böhm he co-initiated the Centre for Plausible Economies, a research cluster devoted to reimagining economy by using artistic means. In 2020 he co-established the Office for Postartistic Services, the aim of which is to employ artistic competences in support of progressive social movements. He is editor and author of several catalogues, books, readers, chapters, essays and articles, devoted to social, economic, and theoretical aspects of the contemporary art. Current research interests include interdependent curating, new models of artistic institutions, postartistic theory and practice. His book The ABC of the Projectariat was published in 2021 by the Manchester University Press.

Aleksandra Janus

Aleksandra Janus is an anthropologist, researcher, curator of cultural projects. She is a graduate of doctoral studies in Anthropology at the Jagiellonian University and co-founder of Museum Lab training program for Polish heritage professionals, head of the Open Culture Studio and board member of Centrum Cyfrowe. She co-founded Muzea dla klimatu initiative (Museums for Climate) and co-cratered Exercising Modernity Academy. She works with institutions looking for effective ways of engaging their visitors and supports them in sharing open resources. In her academic work she analyzes cultures of remembrance and the role of institutions in the process of institutionalizing discourse about the past.