Tytuł

Locating collaboration On Affinity Institution

https://www.doi.org/10.48285/ASPWAW.29564158.MCE.2022.8.6

https://miejsce.asp.waw.pl/locating-collaboration-on-affinity-institution/

Abstrakt

The following essay focuses on the similarities and differences in situated, community-based curatorial practices that address pressing social and environmental issues applied in diverse contexts. Nierodzińska examines contemporary curatorial strategies based on commoning and collaboration to answer the question: is collectivism linked to a specific cultural space? Nierodzinska’s reflections, which focus on analysing contemporary curatorial strategies and her own curatorial and activist practice, are rooted in both the concept of New Institutionalism and the local historical concept of the Museum of Current Art. Based on her practice and the theoretical framework mentioned above, the author proposes the project of affinity institution as a possible direction of development for cultural institutions in Poland.

DOI

Introduction

In the following essay, I will look at contemporary curatorial strategies based on commoning 1 and collaboration as applied recently at documenta 15 as an organisational method, while at the same time attempting to answer the question: is collectivism assigned to a specific cultural space? Can it only develop in its fullness within a certain context? What makes up this context? I will base my reflections on New Institutionalism, Institutional Critique, the concept of Museum of Current Art, the documenta exhibition held every five years in the German city of Kassel, with focus on the editions: 15, 12 and 11, and on my own curatorial and activist practice. In the last part of the text, I will introduce the term Affinity Institution [instytucja sojusznicza] to describe a possible direction of development for institutional practices in the field of art in Poland.

The New Institutionalism

Collectivism tends to develop in contexts where institutions do not fulfil their social roles, arising from need rather than choice. In a 2006 text, Austrian philosopher and cultural critic Gerard Raunig develops the concept of instituent practices 2 as a continuation of the Institutional Critique 3 begun in the mid-20th century. In opposition to the historical Institutional Critique, the instituent practice is an ongoing process aimed at increasing participation understood as political engagement rather than mere contestation or incorporation of already existing power relations. It is expressed, for example, by an act of speaking unfettered by conventions called parrhesia, from the Greek ‘to say everything’, described by Michel Foucault 4 as a deconstructive, emancipatory method. Here, the institution is understood as a set of norms, modes of interaction that constitute society, and not only as a specific state apparatus. In the field of art, which is itself a dispositif based on concrete social rituals, it is exhibitions and/or events that are forms of expression.

Understood as part of a social discourse rather than as a method of presenting autonomous artworks, they expose the sensitivities of the contexts in which they take place. In countries where religion plays an important role, these tend to be ideologically contentious issues related to the taboo of repressed sexuality and the restriction of reproductive rights, while in countries burdened by a history of colonial and war crimes, and especially in the case of Germany -- with genocide, it is sensitivity to the rights of minorities, mainly the Jewish diaspora, while voices from former German colonies do not resonate with the same intensity. The greatest difficulty in speaking from the position of a racialised subject here, might be the need to do so from a position that does not recognise anti-Semitism, and from the perspective of a person experiencing anti-Semitism from one that silences racist exclusions. However, these positions might be reinforced in the way that they point to the top-down power structures that put them in the role of the Other in the first place.

Raunig argues, following Deleuze and Foucault, that fleeing is the most active form of engagement in a debate, at the point where it is impossible to sustain dissent. Retreating to safer positions offers an opportunity for reflection and regeneration, but at the same time does not imply an eremitic hermitage or confinement to an alternative subcultural enclave. Rather it is part of a process of grappling with power; refusing to be ruled in this particular way, not rejecting power based on ‘common sense’ 5 altogether but remaining with it in a continuous critical exchange resulting eventually in shifts and changes. Raunig writes of the transversal quality of this exchange, which goes far beyond the particular limitations of single fields. In this intersection of realms, he sees the political potential of a cultural and instituent practices, which reject both, the conservative defeatism that closes critical practice to a self-referential, established professional field, and the romanticized notion of the absolute outside, imagined as a place beyond the power relations. The transformative quality of parrhesia would then lie in its transgressive role, which involves speaking dangerous truths, betraying existing paradigms, unlearning habits, queering discourses, being disloyal to common sense rationality and to embrace an act of fleeing as a possibility, while still remaining in exchange with the institution understood as a set of rules, which organise and stabilise social life: ‘Avoiding both polarizations suggests a movement of exodus, of defection, of flight, but looking for a weapon while fleeing . There is a red thread that runs from Max Stirner’s remark about ‘leaving what is established’, which turns into decay in the act of leaving, to Gilles Deleuze’s concept of the lines of flight, (…) the differentiated construction of a non-dialectical way out of purely negating and affirming the institution.’ 6

During five years of work as a deputy director at the Municipal Gallery Arsenal in Poznan, I have tried to connect my activist background with the possibilities provided by the municipal institution. I translated the concept of instituent practices into collective and community-based exhibiting. With the exhibition Politics of (In)Accessibilities, Citizens with Disabilities and Their Allies 7 (2022) focusing on the rights of disabled 8 and queers, but also before that, together with artists and collaborators, I supported processes that on one hand deconstruct the authoritarian structures of the institution, and on the other enable the access to it for marginalized groups and individuals. I have sought to transform the gallery into an active participant in the public debate, standing on the side of marginalized groups, supporting labour rights and sustainable practices, as well as challenging what is considered the ‘norm’ in neoliberal, far right, and extremely Catholic society of contemporary Poland. Today, when I no longer work at the gallery, I have to state that without the support of revolutionary, social movements that could lead to a general change in the political and social situation in Poland, it is very difficult, if not impossible, to continue a progressive exhibition and education programme within official structures.

Lumbung

My reflection on collaborative practices started in Kassel while visiting documenta 15, the latest iteration of one of the world’s largest contemporary art exhibitions. The curatorial work was carried this time by a collective for the first time, and for the first time from outside Europe. 9 The ten-member ruangrupa decided to build the curatorial concept around the notion of lumbung, which in Indonesia describes a collectively governed rice barn. Lumbung became a concept central to the cosmogony of the exhibition, according to the Indonesian collective; the watchword being the principle: ‘make friends not art’, where humour, generosity, curiosity, sufficiency, independence, localness, transparency, and regeneration counted more than the originality, extractivism and individualism attributed to Western paradigms of artistic production. The curators and a group of associated artists and activists sought a community approach that would challenge the existing hierarchical, top-down management of the exhibition, which has been organised every five years since 1955.

Ruangrupa initially invited 14 collectives, which on their side added around 50 other collaborators each, mostly from the so-called Global South, to participate in the 100-day event, calling documenta 15 the ‘lumbung first’. Communication between the artists and the curators took place on a majelis basis, i.e. working in subgroups that met regularly, due to the pandemic, mostly online. An important principle was not to produce works specifically for the exhibition, but to ‘translate’ the processes started in the places of origin. This was most often done by means of film, interviews or installations made up of traces left over from past events. Noteworthy at this point are the translations of the collectives: Wajuuku Art Project from Kenya, Atis Rezistans and Ghetto Biennale from Haiti, Wakaliga from Uganda, and by the controversial Taring Padi from Indonesia, whose large-format banner People’s Justice (2002) drew a justified wave of criticism for its depiction of anti-Semitic caricature. All have in common the integration of educational processes with artistic production based on the building up a community, in spite of poverty, exploitation by the First World and other forms of everyday violence. In the activities of the Atis Rezistans (artists of resistance), a collective founded in the late 1990s, collaboration is based on the Creole concept of konbit 10 , voodoo symbolism and the memory of the Haitian revolution (1791-1804) 11. The practice of the Wajuuku Art Project reflects the living and working conditions in the Lunga Lunga slum in Nairobi, which are marked by constant temporariness and a struggle against adversity called by the members ‘improvised functionality’. Wakaliga, on the other hand, is a film studio on the outskirts of Kampala, Uganda, which for two decades has produced cult action films known around the world, such as Who Killed Captain Alex? (2010) or Bad Black (2016). Finally, Taring Padi, an Indonesian collective founded in 1998 in Yogyakarta, at a time of mass protests and riots that resulted in the overthrow of Suharto’s more than 30-year dictatorship, which was supported by the West. The practice of the collective is directly linked to its political commitment that characterises resistance to Western hegemony and capitalism. The banners, graphics and slogans produced by the collective demand social justice, economic equality and self-determination, at the same time using propagandist techniques in simplistic visual language consisting also of elements of anti-Semitic symbols, like a caricature of a Jewish banker. Unfortunately, the works made by the collective were left without critical comment by curators and organisers, which might have clarified the historical context, but also underlined the ongoing violence of using anti-Semitic representations.

In relation to the activities of the Taring Padi, among others, ruangrupa faced accusations of not being sensitive enough to enter into dialogue with the local historical and political context. Nevertheless, it should be mentioned here that the German mainstream press began accusing the curators of anti-Semitism a few months before the exhibition even started, based on an unverified blog post by the so-called ‘Alliance against Anti-Semitism Kassel’ 12 a criticism that escalated after the presentation of Taring Padi’s ‘People’s Justice’ banner, prompting Der Spiegel columnist Sasha Lobo to call the mega-exhibition ‘Antisemita’ 13 The curators and artists responded with a letter 14 listing a number of racist attacks which they experienced together with invited artists in the city of Kassel, adding to the online harassment. An open discussion to quell emotions, contextualise postcolonial perspectives and explain German memory debate in order to find common ground in this processual exhibition in advance or even a few days before its closure seems rather impossible. The texts produced by supporters of the ruangrupa’s organizational agenda, such as the one by Gregory Shollete 15 in e-flux or those who identify with the criticism of the show, do not calm the situation, but rather reinforce the antagonisms between the claimed and projected ideological purity of activists from the Global South and the conservative institutional exclusivity of the Global North. A good punchline here can be found in the opinion of Meron Mendel, director of the Anne Frank Centre for Education, who, while appreciating the exhibition, at the same time notes that the curator’s avoidance of responsibility and refusal to participate in an open, public debate is objectionable. 16 The withdrawal from public debate by Indonesian curators may have been due to the intensity of German discourse. Still, if ruangrupa aimed to break the paradigms of how Western European institutions function not only through the representation of collectivism, but if it had backed it up with actual performance, i.e. participation in the discussions and controversies surrounding the reception of the works presented at documenta 15, the processes of commoning could develop in the real, discursive space and not only in the protected heterotopy of art.

Gotang Royong

The results of the curatorial work of ruangrupa in Kassel reminded me of the exhibition at Center of Contemporary Art Ujazdowski Castle in Warsaw entitled Gotong Royong. Things We Do Together 17 . In addition to the concept and aesthetics, the two events are related by the participation of the Jatiwangi art Factory collective, whose work involves creating community in the post-industrial, rural Indonesian landscape from which it takes its name, using clay as a local material with multiple uses. For the collective, this means remaining in dialogue with the context in which it operates by organising the New Rural Agenda activist conference, a film and music festival, a residency programme and running its own radio and television station. The collective continues a tradition of community work called gotang royong in Indonesia, which means ‘mutual assistance’. It is a traditional practice of community life that is based on putting the well-being of the community above individual benefit.

Gotang royong, before it became the title of an exhibition at the CCA in Warsaw, was also used as the programmatic political slogan of Indonesia’s first two post-colonial and nationalist presidents, Sukarni and Suharto. During the dictatorship of the latter, collective action changed its official status and began to signify forms of resistance. In socialist Poland, the equivalent of community work was the czyn społeczny [social action] initiated during the communist period by, for example, workplaces or schools. In Russian-speaking countries and in the Ukraine, voluntary work for the community is called subotnik 18 . As Vanessa Gravenor rightly observes in her review of the Warsaw exhibition 19 , participatory practices taking place in cultural institutions often have little to do with the broader context in which they are situated. At the CCA in Warsaw, the practice of the culturally distant gotang royong provided a sense of temporary comfort and security in a country where People of Color, Romani, Muslims, Jews and migrants often face xenophobic violence. The exhibition’s participants entered into a symbolic dialogue with what is outside the Institution 20 but no longer with what belongs to it, leaving without comment the invisible, feminised curatorial and administrative work and the character of the place defined top-down, by a director appointed every few years, currently an art historian with extreme right-wing views 21

Exhibition as process

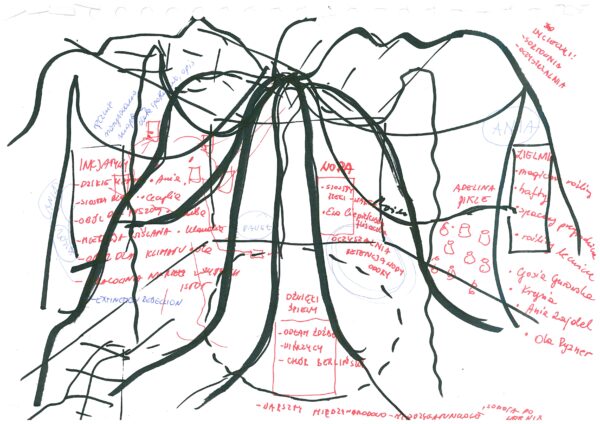

A municipal gallery, unlike a museum (dependent on the municipality and external fundings and not on the ministry of culture) can be less dependent on the state authorities and therefore be more critical participant in the public debate. It can, to some extend and not without consequences, support the demands of marginalised groups, especially in a country like Poland, where human rights are systematically violated (the pushbacks on the Polish-Belarusian border, the restrictions on reproductive rights or the economic pressure on disabled people and their families). During my work at the Municipal Gallery Arsenal, I was aware of this discursive role of the institution and wanted to use it to support and stabilise grassroots, civic processes. Combining activist experience with academic background, and the opportunities provided by the municipal gallery, I co-curated situations and exhibitions that addressed the relevant social and environmental issues: Workshops of Revolution (2018), Girlhood and COVEN Berlin present: BEDTIME (2018), Creative Sick States: AIDS, CANER, HIV (2019/20), Magical Engagement (2020) and Politics of (in)Accessibilities, Citizens with Disabilities and Their Allies (2022) 22 . In the case of Creative Sick States… and The Politics of (In)Accessibilities… a key element was the theme supported by the artistic research around which the exhibition and the accompaning programme were organised. In this context, we addressed issues of sickness solidarity based on support groups operating in Poland, such as the Amazons (women with breast cancer) or an NGO Positive in Rainbow supporting people living with HIV. The activities undertaken were aimed at reflecting on the role of the institution and using it to take a stand in the social debate, which resulted in a number of controversies 23 The idea was to challenge the autonomy of the cultural institution, to show it as a place where the debate about sickness, about public health system, and grassroot solidarity can take place and to do so through art. Taking this opportunity, artists/activists started to treat the gallery as a platform to speak about the needs of vulnerable subjects, which is part of their ongoing practice. Thus, the gallery became a forum, a place for discussion and dissent that needed to be addressed.

Without equating the programme of a local municipal gallery with the work of the collectives participating in documenta’s three-month mega-exhibition, I would like to reflect on the notion of collectivism that links organizational methods applied in this both contexts. Ruangrupa refers it to processes typical of the Global South, which are juxtaposed with the modernist principle of individuality ascribed to the artmaking of the Global North. Although I understand the activist’s need for a clear-cut thesis around which the exhibition is structured, here based on North/South: individualism/ collectivism, colonisers/colonised dichotomies, this also leads to inevitable simplifications and omissions, and tends to self-exoticise the positions of the curators and invited artists. Looking at and participating in the institutional organisation of the art field, I share a dislike for its hierarchical nature, the frequent lack of transparency in decision-making, the absence of reflection on the politics of invitation and power structures, the continuation of racialising, sexist and ableist practices. I wonder, however, if these are not problems that are unfortunately quite common in the field of art – a field based on personal preferences and lacking objective points of reference -- and that occur in every latitude. I think of previous editions of documenta, from which the ruangrupa distanced itself at the outset by emphasising its lack of interest in hegemonic, i.e. European, ways of producing knowledge, which is understandable, given the post-national-socialist history of the Weltausstellung 24 , but without carrying out solid research, the curatorial group inevitably placed itself in the romantic, utopian position of the ‘pure subject’ untainted by power relations characteristic of the discourse of the early Institutional Critique 25 . Working in and with an institution, however, means recognising the context in which one operates, taking into account the programme put in place by one’s predecessors, whether through its continuation or official negation, as well as exploring the possibilities available at a given time.

Workshops with the collective Army of Love as part of the exhibition: „Workshops of Revolution”, 2018, Photo: Irek Popek

documenta 12 and transformative education

Preparing to write this text, I looked at the materials and knowledge produced at documenta 12, during which, for the first time, there was such a strong emphasis on education and a reworking of the colonial history of the exhibition medium and the associated institution of the museum. The educational work of the 2007 exhibition in Kassel was described by educator and researcher Carmen Mörsch in the text: ‘At a Crossroads of Four Discourses; documenta 12 Gallery Education in between Affirmation, Reproduction, Deconstruction, and Transformation 26 . She highlighted the critical and transformative role of dissent-based education, which aims to change institutional paradigms, break the exclusivity of art and, above all, deform it through the active participation of actors from diverse cultural backgrounds. She contrasted the deconstructive, critical concept of education with an affirmative one characterised by an excessive, infantilising enthusiasm that preserves the institutional status quo. The aim of the educational programme developed as part of documenta 12 was to change the ways in which the works and performances presented in the exhibitions were interpreted. Institutions stripped of their function of authority were to become platforms for multi-directional discussion, actively unlearning racialising, anti-feminist and ableist schemes and introducing egalitarian solutions. Prior to documenta 12, there had also been earlier efforts to democratise institutions, albeit in a much less critical way, such as Bazon Broch’s one-way didactic, paternalistic Besucherschule [vistitors school] implemented during documenta 4 to 7, or Joseph Beuys’ socio-ecological action 7000 Eichen -- Stadtverwaldung statt Stadtverwaltung [7000 Oaks – City Forestation Instead of City Administration] (1982) 27 . Both initiatives were based on strong, masculine personalities: Professor Broch, who called himself: Denker im Dienst und Künstler ohne Werk [Thinker in service and artist without work], and a visionary artist with an extraordinary biography in the case of Beuys. Both actions are the most frequently cited examples of socially engaged art in the context of documenta. By contrast, the educational activities of the largely feminised documenta 12 team, even if it has so far been a major game-changer when it comes to art education, are barely known beyond professional discourse.

Postcolonialism

Postcolonial critique emerged as early as during documenta 11 in 2002, curated by Nigerian-born Okuwui Enwezor. His ambition was to define the place of art and culture in a globalised world, its impact and its connections to other knowledge systems. The exhibition in Kassel was the last of five platforms that were organised a year before documenta opened in various cities around the world: Berlin, Vienna, New Delhi, St. Lucia and Lagos. Their task was to discuss and work on themes related to democracy as an unfinished process, to the somewhat pompous question of truth and reconciliation, to the state of siege in the context of African metropolises and to the process of creolisation. Many of these themes have returned in the current editions of documenta. The collectivisation of creative processes, their connection to life and politics, as well as postcolonial themes have been appearing at documenta for over 20 years now.

The thesis of Indonesian curators team that community-based creative processes are the domain of the Global South and that their implementation in a mega exhibition this year in Kassel was a game changer is therefore hard to sustain. I tend to think this kind of approach contradicts what was meant to be criticised, which is context-free universalism. Exhibiting collectivist practices developed in different locations is not an effective antithesis to neo-liberalism, which easily takes over and fetishises participatory art taking place in non-European contexts. When representing collective practices, however, it is necessary to take into account not only the context in which they originate, but also in which they are exposed. The method of ‘translating’ geographically and culturally distant practices and redistributing resources are moves in the right direction, but they still do not challenge the hegemonic structures and power relations on which the largest Western European arts festival is based.

In the Polish art context, which exists on the European peripheries, the engaged localism in a much smaller scale is practiced, for example, by the grassroots organised cultural place DOMIE 28 based in Poznan, which operates on an experimental basis: Anyone who knows where the keys to DOMIE are, can stay and make art or just spend time there. The functioning of the place is taken care of by a collective of four people: Agata Knieć, Martyna Miller, Katarzyna Wojtczak and Rafał Żarski. DOMIE hosts exhibitions, birthday parties, encounters, residencies, concerts and neighbourhood picnics in the very heart of the gentrified city centre. Most importantly, the space, which is owned by the city and gets its operating funds from grants and crowdfunding, is a space that organises the community around itself. When DOMIE was invited to an exhibition in the Museum of Modern Art in Warsaw, Katarzyna Wojtczak and Martyna Miller, instead of showing representations of collective work, organised a counselling centre for artists and activists who run independent cultural spaces such as theirs. 29

The reason why local engagement works out better for grassroots, artistic collectives is that they are on their own from the beginning, they don’t delegate the work to others, but deal with the organisation and conception within their own means and capabilities. This causes other problems than in an institution or at mega-exhibition, e.g. overwork, work without financial gratification and consequent burnout, but it also gives much more independence and the much greater acceptance for making mistakes, for which only the people directly involved are responsible. Art collectives that co-create places that are important to their communities often do not feel obliged to take responsibility for everything that happens in the place where they operate, they leave the structures open. The situation changes when the place of their activity is a public institution, with its history, power relations, public fundings, and social and educational mandate. This is when the art collective in the role of curators becomes an active participant in a public debate with its many points of reference (public opinion, media, politics of memory, etc.).

The critical institution and the Museum of Current Art

In Poland, the topic of New Institutionalism, i.e. the socially engaged institution, is mainly known from the book Muzeum krytyczne [Critical Museum] 30 by Piotr Piotrowski. In it, the art historian gives an account of his year-long management of the National Museum in Warsaw which culminated in his resounding dismissal from the director’s position. The professor-curator aimed to make the museum a forum directly involved in public debate, self-reflective and critical. However, the ambitions were met with mundane, materialistic obstacles related to the resistance of the employees of the conservation department and the hostility of the administration. The museum proved not to be ready for revolutionary change. During his short tenure, Piotrowski nevertheless managed to organise a very important exhibition, Ars Homo Erotica (2010), curated by Paweł Leszkowicz. The theme of the exhibition was the male nude in the museum’s collection, expanded to include contemporary works by queer Polish artists. From a lesbian perspective, the exhibition was criticised for being male-centric. Warsaw audiences were divided; the exhibition was very successful in terms of attendance, but it also sparked outrage due to its combination of history and queer erotica. Ars Homo Erotica was praised in Maura Reilly’s book Curatorial Activism, Towards an Ethics of Curating (2018) and named one of the most important exhibitions in the world giving a queer perspective to a museum collection. 31

The Critical Museum has much in common with another historic idea for an institution, namely the Museum of Current Art, which was dreamt of in the 1970s by a well-known Polish art historian: Jerzy Ludwinski. The place of culture he described was to be located outside the centre, in Wrocław, and, in contrast to the classic museum-mausoleum that preserves and systematises the past, was to organise ‘continuous artistic events’ that would react to changes as they occurred: ’ (…) The Museum of Current Art must provoke artistic facts, accelerate them, simply be a place where new art is born, be its sensitive seismograph, and also a catalyst’ 32 . In Ludwiński’s view, the institution should be more like a studio or a workshop than a place for presenting completed artworks. It ought to be divided into action, visual experiments, collection, art popularisation, publishing and technical departments. In Ludwiński’s vision, the opening of the Museum of Current Art would be preceded by a symposium at which industry and art would meet. The idea of this dream institution has not yet been fully realised, but traces of it can be seen in the activities of some cultural places in Poland, such as, for example, the Museum of Modern Art in Warsaw, Wrocław Contemporary Museum, Muzeum Sztuki in Łódź and the Laznia Centre for Contemporary Art.

Affinity Institution

Currently, the biggest problem for institutions in Poland, apart from the top down hierarchical structure and the replacement of management by the current regime, is economic censorship. Therefore, the alliances postulated already by Jerzy Ludwiński in his Museum of Current Art, are indispensable. They could be realized by i.e. supporting processes initiated by marginalised groups, making them space, enhancing their visibility, sharing competences and resources, testing more egalitarian, solidarity-based ways of coexisting in a world for which cultural workers also take responsibility. A good example of this cross-institutional collaboration was a protest in support of those unlawfully detained at the border between Poland and Belarus 33 , and now is sharing institutional resources with activists and war refugees from Ukraine 34 . Such a supportive function of the institution, which goes beyond a dialectical, critical approach and requires active engagement, is presented by what I call: the Affinity Institution. The later draws on the experience of New Institutionalism, which changes institutions from within; on the concept of a critical institution that actively participates in and often initiates social debates, on the idea of the Museum of Current Art as a site-catalyst for socio-artistic events, and on the ongoing process of instituent practices, which avoids the reproduction of already known forms of governance. During my five years of work at the Municipal Gallery Arsenal, I tried to put the above concepts into practice, through exhibitions in process (Workshops of Revolution, Magical Engagement, Creative Sick States: AIDS, CANCER, HIV, Politics of (In)Accessibilities...), whose educational and discursive programmes were linked to the exhibition concept from the very beginning, and through which cross-sectoral collaborations between artists, curators, activists, educators and community workers were made possible. I was interested in co-creating a place that would gather the community around it, to subvert the representational role of the gallery, to transform it into a common place by holding open calls for exhibitions, collaborating with grassroots collectives and taking the side of progressive social movements. An extension of these efforts is the publication of RTV Magazine 35 , which is both an online platform and a print format. Each of its issues is dedicated to a different theme combining social and environmental engagement with art context. The results of these practices and collaborations were not always visually pleasing, but they did something more important, they pointed the way to possible ways forward.

Curatorial guided tour through the exhibition: „Creative Sick States: AIDS, CANCER, HIV”, 2019, Photo: Maciej Krajewski

It is allied institution with its stable funding, alongside informal collectives, that could help to define new institutional desires and materialise them in a cultural field in urgent need of change. It is important to have a broad discussion, critique and speculation about possible institutional futures, preferably continuing discourses started in the past. Turning our backs and allowing politicians to take over institutions is already having a dramatic effect in Poland and other illiberal countries, where state funding only supports venues and initiatives that are uncritical of the current regime, so with few exceptions all progressive artistic production is non-governmental and grassroots. With this authoritarian revolt in my homeland in mind, I read the final letter signed by the curators and participants of documenta 15 36 In it, the lumbung curators and artists point out justifiably the unequal standing towards documenta as a national institution with its Eurocentric, or rather Germanocentric, agenda. However, they are too hasty to renounce further cooperation with documenta and propose instead the development of a transnational lumbung. Hopefully, this is one more, but not the last, argument in the ongoing debate on forms of collaboration, in which grassroots movements provide the basis for talking about and actually performing institutions of commons, unlearning top-down discipline and establishing new forms of assembling and constituting. If not documenta, then some other emerging organisational form will have to face legitimate critique and turn it into an opportunity to develop into a more inclusive, open structure, working through the colonial and/or national history that underpins it, rather than trying to avoid it by creating the illusion of an alternative in short cuts.

And in the end, coming back to the question of whether community-based activities belong to particular cultural space, the answer is: no. They are happening everywhere, thus they are universal, because the economic, ecological and political situation in many countries of the world makes them indispensable. They could be a source of transnational solidarity, if the situated contexts from which they originate and in which they are presented are not overlooked. 37

- Lat. Communis, refers to self-organised and needs-oriented joint production, administration and care. Commoning designates those social practices that can be described as „equal togetherness in joint action”. ↩︎

- Gerald Raunig, ‘Institutional Critique, Constituent Power, and the Persistence of

Instituting,’ Transversal, 01.2007, https://transversal.at/transversal/0507/raunig/en (accessed: 23rd August 2022). ↩︎ - Institutional critique is the systematic inquiry into the workings of art institutions, such as galleries and museums, and is most associated with the work of artists like Michael Asher, Marcel Broodthaers, Andrea Fraser or Adrian Piper. ↩︎

- Michel Foucault, Discourse and Truth: The Problematization of Parrhesia, six lectures given by Michel Foucault at Berkeley, Oct-Nov. 1983. https://foucault.info/parrhesia/ (accessed: 6th January 2023). ↩︎

- I use “common sense” in the Gramscian understanding of the term as hegemonic culture, which propagated its own values and norms so that they became the values of all. People in the working class identified their own good with the good of the bourgeoisie and helped to maintain the status quo rather than revolting. ↩︎

- Raunig 2007. ↩︎

- https://arsenal.art.pl/en/exhibition/politics-of-inaccessibilities/ (accessed: 21st of September 2022). ↩︎

- In Polish context the most correct expression is people with disabilities, in English disabled people. I will use them both interchangeably. ↩︎

- In 2002, Nigerian-born curator Okwui Enwezor was responsible for the documenta 11. ↩︎

- Konbit has a few meanings in Haitian Kreyol. Sometimes it is used as a verb, and means ‘to put your hands together’. Other times, it is a noun, meaning, ‘communal or cooperative labor’. The essence of Konbit is community and equality. ↩︎

- The Haitian Revolution was a successful insurrection by enslaved people against French colonial rule. The revolt began on 22nd August 1791, and ended in 1804 with the former colony’s independence. ↩︎

- BGA Kassel, https://bgakasselblog.wordpress.com/ (accessed: 21st September 2022). ↩︎

- Sascha Lobo, ‘Willkommen auf der Antisemita 15’, Spiegel on-line, 22.06.2022, https://www.spiegel.de/netzwelt/netzpolitik/sascha-lobo-ueber-den-documenta-skandal-willkommen-bei-der-antisemita-a-424a0c6f-ec04-4158-92be-9ab8f03f17ad (accessed: 21st September 2022). ↩︎

- Ruangrupa, ‘Anti-Semitism Accusations against documenta: A Scandal about a Rumor!’, e-flux on-line, 07.05.2022, https://www.e-flux.com/notes/467337/diversity-as-a-threat-a-scandal-about-a-rumor (accessed: 21st September 2022). ↩︎

- Gregory Sholette, ‘A short and incomplete history of “bad” curating as collective resistance’, e-flux on-line, 21.09.2022, https://www.art-agenda.com/criticism/491800/a-short-and-incomplete-history-of-bad-curating-as-collective-resistance (accessed: 23rd of September 2022). ↩︎

- Meron Mendel, ‘Großteil der documenta-Künstler wurde zu Unrecht in Mitleidenschaft gezogen’, Hessenschau on-line, 21.09.2022, https://www.hessenschau.de/kultur/meron-mendel-grossteil-der-documenta-kuenstler-wurde-zu-unrecht-in-mitleidenschaft-gezogen,mendel-interview-documenta-102.html (accessed: 23rd of September 2022). ↩︎

- Gotong Royong. Things We Do Together was an exhibition in process organised in 2018 as a result of residency trips to Indonesia by two Polish curators, Marianna Dobkowska and Krzysztof Łukomski. ↩︎

- This year, people fleeing the Russian invasion of Ukraine who found temporary shelter in Poland, wanting to repay the local communities, organised spring subotniki (ukr. суботник), in which they cleaned parks. ↩︎

- Vanessa Gravenor, ‘Things we do together at Ujazdowski Castle in Warsaw’, Temporary Art Review, 04.01.2018, https://temporaryartreview.com/things-we-do-together-at-ujazdowski-castle-in-warsaw (accessed: 17th August 2022). ↩︎

- The Fresh Market project with participation of labour migrants from Belarus and Ukraine living in Poland by the Open Group from Ukraine, namely Yulia Kosterieva and Yuriy Kruchak, should be mentioned here. ↩︎

- Since 2020, the institution has been run by art historian Piotr Bernatowicz, appointed to this position by the ruling party. ↩︎

- More about the exhibitions at www.arsenal.art.pl ↩︎

- https://www.radiopoznan.fm/informacje/kultura/galeria-arsenal-przekracza-kolejne-granice (accessed: 23rd August 2022) or: https://oko.press/prawicowa-nagonka-na-galerie-arsenal-abp-gadecki-polskie-radio-i-radni-pis-twierdza-ze-prowadzi-warsztaty-aborcyjne (accessed: 3rd August 2022). ↩︎

- The exhibition documenta. Politik und Kunst at Deutsches Historisches Museum in Berlin in 2021 presented the problematic history of documenta from its begining: https://www.dhm.de/ausstellungen/archiv/2021/documenta-politik-und-kunst/ (accessed: 24th September 2022) ↩︎

- I am thinking of the artists working in the 1960s and 1970s, such as Marcel Broodthaers, Hans Haacke or Mierle Laderman Ukeles. They positioned themselves in opposition to the institution by presuming to remain outside of it. ↩︎

- Carmen Mörsch, ‘At a Crossroads of Four Discourses. documenta 12 Gallery Education in between Affirmation, Reproduction, Deconstruction, and Transformation’, Documeta 12, Education, 3-31., https://www.diaphanes.net/titel/at-a-crossroads-of-four-discourses-1032 (accessed: 23rd August 2022) ↩︎

- The tree-planting campaign was intended to draw attention to increasing urbanisation and the lack of sustainable urban development. The artist called the action he initiated ‘Soziale Plastik’, i.e. a performance with the community in which anyone and everyone ‘can become an artist’; the oak trees planted by the volunteers can still be seen in the space of Kassel today where the planting is a continuous project. ↩︎

- http://domie.pl (accessed: 21st of September 2022). ↩︎

- https://artmuseum.pl/pl/news/poradnia-domiedispensary (accessed: 22nd of September 2022). ↩︎

- Piotr Piotrowski, Muzeum krytyczne [Critical Museum], Poznań: Rebis, 2011. ↩︎

- Maura Reilly Curatorial Activism, Towards an Ethics of Curating, Thames and Huston, London 2018. ↩︎

- Jerzy Ludwiński, Sztuka w epoce postartystycznej i inne teksty [Art in the post-artist epoch and other texts], Poznań and Wrocław: Academy of Fine Arts in Poznań and BWA Contemporary Art Gallery 2009, 225. ↩︎

- www.petycjeonline.com/apel_rodowiska_kultury_w_sprawie_sytuacji_na_wschodniej_granicy_rzeczpospolitej_polskiej(accessed: 21st of September 2022) ↩︎

- https://artmuseum.pl/en/cykle/slonecznik-solidarny-dom-kultury (accessed: 22nd of September 2022). ↩︎

- www.magazynrtv.com (accessed: 21st of September 2022) ↩︎

- “We are angry, we are sad, we are tired, we are united: Letter from lumbung community”, e-flux online, 10.09.2022, https://www.e-flux.com/notes/489580/we-are-angry-we-are-sad-we-are-tired-we-are-united-letter-from-lumbung-community (accessed: 23rd of September 2022). ↩︎

- About the lack of context during the documenta 15 wrote an artist and author based in Berlin: Hito Steyerl, ‘Kontext ist König, außer der deutsche’, Zeit on-line, https://www.zeit.de/kultur/kunst/2022-06/documenta-15-postkoloniale-theorien-kunst-kontextualisierung?utm_referrer=https%3A%2F%2Fwww.google.com (accessed: 25th September 2022). ↩︎

Zofia nierodzińska

Zofia nierodzińska is an author of texts, curator, cultural worker, artist, activist, deputy director of the Municipal Gallery Arsenal in Poznań between 2017-22. She studied at the University of Arts in Poznan (PhD) and the Universität der Künste in Berlin (MA). She is the curator and co-curator of exhibitions including: „The Romantic Breast Cancer Adventures of Beth Stephens and Annie Sprinkle”, „Creative Sick States: AIDS, CANCER, HIV’ or ‘Politics of (In)Accessibilities, Citizens with Disabilities and Their Allies’ at the Municipal Gallery Arsenal in Poznan. She is the editor-in-chief of the platform on art and activism Magazyn RTV (www.magazynrtv.com). She has published inter alia in: dwutygodnik, Czas Kultury, Neues Deutschland, Analyse und Kritik, Missy Magazine, Przegląd Kulturoznawczy, Miejsce and BLOK Magazine. Together with Jacek Zwierzynski, she edited the publications: „Creative Sick States: AIDS, CANCER, HIV and ‘Acting Together’. She is currently working on the publication ‘Politics of (In)Accessibilities’ and on the book ‘Affinity institution’ as a scholarship holder at the Senatsverwaltung für Kultur und Europa. She works as an editor and curator at Berliner Festspiele. For the past few months, after a series of repressions from the authorities and the church and after losing a trial for ‘insulting religious feelings’, she has been living with her partner and dog in Berlin. For her, Polishness is inextricably linked to trauma, so she tries to function in transnational constellations.