Tytuł

Minor Remnants from Solna Street Isaac Celnikier’s Post-war Sketches and the Holocaust Experience

https://www.doi.org/10.48285/8kaewzfo3p

https://miejsce.asp.waw.pl/english-minor-remnants-from-solna-street-isaac-celnikiers-post-war-sketches-and-the-holocaust-experience/

Abstrakt

When Isaac Celnikier (1923-2011) decided to emigrate to France, reacting to the escalation of anti-Semitic sentiments in Poland in 1957, he left behind artwork he had created in the 1940s and 50s. Among these was a collection of illustrations for Yiddish short-stories, written by Abraham Reisen in the first three decades of the 20th century and published in one volume by the “Yiddish Bukh” publishing house in 1957. Although in a letter to Aleksander Lewin, his educator at the Janusz Korczak’s Orphanage, Celnikier called this collection “minor remnants from Solna street which are of little importance,” these are artworks that he created during the post-war period, a quintessential testimony that he left behind. He survived the Bialystok ghetto, the Stutthof, Auschwitz III (the so-called Buna) and Flossenbürg Nazi camps. Around April 20, 1945, he was found by American soldiers under a pile of corpses. In the artist and survivor’s post-war reading, the stories of Reisen were construed as a prefiguration of the Holocaust. In the sketches analyzed, Celnikier projected his own personal experience of the Shoah: the breakup of family ties, disconnection from the continuity of Jewish tradition, and the border experience of surviving under a pile of corpses.

DOI

“As far as I know, many drawings have found their way to Lida’s circle of friends, I don’t know how and to whom, but I’m not going to pursue this.”1

When Isaac Celnikier (1923-2011) decided to emigrate to France, reacting to the escalation of anti-Semitic sentiments in Poland in 1957, he left behind artworks he had created in the 1940s and 50s. Much of this was in the possession of Celnikier’s partner of the time, the Czech artist Ludmila Stehnová, whom friends called Lida. In her last will, the artist bequeathed her collection of Celnikier’s works to her friend, Jolanta Walicka-Kulesza, who after Lida’s death divided it into two parts, unaware of its story and not knowing that it constituted one unit. She handed over one part, which included 72 works, to the Jacek Malczewski Museum in Radom (currently deposited at the Mazowieckie Centrum Sztuki Współczesnej [the Masovian Centre for Contemporary Art]—“Elektrownia”), whereas the other part, which included 52 pieces, was handed over to the Żydowski Instytut Historyczny im. Emanuela Ringelbluma (ŻIH) [The Emanuel Ringelblum Jewish Historical Institute] The character of this distribution must have been arbitrary, considering it broke up the numerous set of sketches for the oil painting Korea, and also the artist’s illustrations for the collection of Yiddish stories written by Abraham Reisen (1876-1953), which were published in one volume in 1957 by “Yiddish Bukh”2 (Polish transcription: “Idisz Buch”). Although in a letter to Aleksander Lewin, his educator at the Janusz Korczak Orphanage, Isaac Celnikier called this collection “minor remnants from Solna street which are of little importance,”3 these are artworks that he created during the post-war period, a quintessential testimony that he left behind. He survived the Bialystok ghetto, the Stutthof, Auschwitz III (the so-called Buna), and Flossenbürg Nazi camps. He was shot in the leg during the transport from Flossenbürg to Dachau, and around April 20, 1945, American soldiers found him under a pile of corpses. He described it years later in an interview with Katarzyna Nowak:

“They brought us to some village, there were granaries there, I climbed up into one of them. I spent three days there lying, with my nose in the gap between the planks. After three days, dogs found me there, I was kicked out of the granary and beaten with rifle butts, I crawled my way to the pile of corpses. I hid among them, not losing my consciousness for a moment. That’s when Americans found me.”4

The time for the synthesis of the Holocaust experience will not be present in Celnikier’s art until the outbreak of the 1968 anti-Semitic campaign in Poland, in reaction to which he changes his technique and starts creating graphics for the series La Mémoire gravée [Engraved in Memory]. Although the young Celnikier might not have been fully conscious of it, this first, post-war period of his creativity, at the crossroads of socialist realism and the aesthetics of the Arsenal exhibition, bears imprints of the Shoah experience.

This article will focus on the analysis of selected works from the period of his artistic creativity which remains the least known and the least treasured collection in the artist’s oeuvre. Since the works described here were in part illustrations for stories, the analysis will also focus on Abraham Reisen’s texts which were not related to the Shoah, since they were written in the first three decades of the 20th century. Nevertheless, their contents triggered recollections of World War II in the artist, which had an impact on his drawings. In my article I put forward the hypothesis that in his creative work the artist projected his own personal experience of the Holocaust onto Reisen’s stories. Even though they originated in earlier times, Celnikier interpreted some of them as a prefiguration of the Holocaust, and he expressed this in his illustrations.

Celnikier’s life in the immediate post-war period was marked by his attempts to return to places in which he had parted forever from his family and friends, but also by his confrontation with a new regime. The intensity of the events in which he participated at that time made it impossible for him to go through the grieving process. Celnikier—not long before a painter at a copyist workshop in the Bialystok ghetto, run by Nazi officer Oskar Steffen—soon after the war became a painter of Soviet banners and portraits at the camp in Šumperk in Moravia.5 Shortly before the camp was evacuated to the gulags, he managed to escape and, under a false identity, he left Prague and went to Bialystok, aided by the Caritas charity organization. In December of 1945, he found Bialystok ruined. He worked on the exhumation of bodies at the cemetery of the former ghetto in Żabia street, and also engraved names on gravestones.6 In January of 1946 he left Bialystok, and again unlawfully travelled to Prague, where he began studying monumental painting under the direction of Emil Filla, at the UMPRUM Academy of Arts, Architecture and Design.

In 1946 Celnikier painted Człowiek z gwiazdą (A wy mówicie, że Boga nie ma!) [A Man with a Star (And You Say There Is No God!)], and in 1949, the monumental Getto [Ghetto]. After he finished working on these paintings there followed a period when he did not touch upon the subject of the Shoah in his artistic output which lasted until 1955. Most probably it was the effect of external factors—the doctrine of socialist realism that was obligatory at those times—but also because of the mechanism of denial which can often be observed in the biographies of the Holocaust survivors. Dominick LaCapra writes about the sanctification of traumatic events as a form of denial.7 It involves alleviating or concealing the wounds, and creating an impression that actually there is nothing to worry about anymore. Thus, the process of going through grieving is ruled out, and a critical engagement in one’s past is made impossible.8

In 1951, Celnikier completed his studies in Prague, and in 1952 he returned to Warsaw, where he stayed for five years. From 1953 the artist cooperated with the magazines “Nowa Kultura” and “Przegląd Kulturalny,” creating illustrations for the texts that they published. During this time, he illustrated three socialist realist poems, written by Roman Kołoniecki, Andrzej Mandalian, and Konrad Bielski.9

In 1955 Celnikier was involved in the organization of the Ogólnopolska Wystawa Młodej Plastyki [Nationwide Exhibition of Young Art] held at Warsaw Arsenal, which took place on the occasion of the 5th World Festival of Youth and Students under the motto Przeciw wojnie – przeciw faszyzmowi [Against War – Against Fascism]. The artists of the so-called “Thaw Generation” who participated in the exhibition protested against socialist realism on the one hand, and against the colorism attributed to the art of such painters as Jan Cybis, Artur Nacht-Samborski or Eugeniusz Eibisch, on the other. Celnikier reached for a monumental and dynamic form, many others chose the aesthetics of expressionism, which evoked polemics. An Italian art critic, Paolo Ricci, took a negative view of the artists’ return to the tradition of expressionism, calling it a style of the times of Hitler’s rise to power:

“Painting and expressionistic art were a manifestation of the German spirit and expressed the despair of the country that lacked trust and hope. It is hard to believe that today, in a country whose nation is in the process of building socialism, monsters of decomposition are being evoked.”10

Celnikier, who was involved in the organization of the exhibition and who came from Emil Filla’s cubist-expressionist school, responded to it in a polemic with Ricci, and defended expressionism as the style in which, as he believed, the trauma of the Shoah could be expressed in the fullest way.

“He [Ricci–ZBG] does not solve the problem of finding an answer to the question of how the people who have outlived their own nation are supposed to speak about those who were exterminated in the ghettos.”11

The realities of the political thaw that followed Stalin’s death—a greater scope of artistic freedom—and the period of ten years which had passed since the end of the war, were most likely the factors that enabled the artist to go through the process of returning to the theme of the Shoah in his artistic realizations in a somewhat more conscious way than would have been possible at the end of the forties.

Getto [Ghetto] 1955

At Ogólnopolska Wystawa Młodej Plastyki, Celnikier presented Getto which received an award in the category of “Painting.” The acclaimed work was a subsequent version—the original had been created in 1949, at the time he was still a student in Prague.12 On the left side of the depiction a male figure supports the naked body of a dead man. His arms and legs hung limply. The two men are shown against a darker background. On the right side of the painting a woman bent in half attempts to catch the legs of the dead man in a caring gesture, one that is characteristic of Pietà representations. As Marcin Lachowski writes, the version from 1955 differs from the 1949 version by the introduction of another figure by the artist—a boy standing on the right side of the painting in front of the bent over woman.13 The woman and the boy, both clothed, are presented against a lighter background. The shallowness of the frame and the lack of a distinct background deprive the painting of a documentary character. A barefoot boy covered with a mantle looks the viewer straight in the eye. He is the connecting link with reality, referring us at the same time to the Biblical figure of Isaac. Celnikier introduces the element of religiousness in his painting. The figure of the Biblical boy is the embodiment of the artist himself—someone, who has escaped from being sacrificed. He survived to bear witness to the Shoah and to give his testimony to his contemporaries.14

Illustrations for Abraham Reisen’s Stories

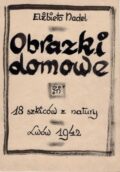

When Celnikier was commissioned by “Yiddish Bukh” to make illustrations for Abraham Reisen’s stories, it was his first and last chance for contact with Jewish culture in post-war Poland. Shortly after this, the artist will emigrate to France and settle there permanently. The “Yiddish Bukh” publishing house existed from 1947 to 1967 and in the course of the 20 years of its activity, it released about 350 titles.15 Its founder, Dawid Sfard, used to say that the main aim of “Yiddish Bukh” was to commemorate the Holocaust and to promote the restoration of Jewish life in Poland.16 Celnikier was as fluent in Yiddish as he was in Polish, so he took on the task. As Eugenia Prokop-Janiec wrote, accentuating the perspective of the Holocaust became the essential feature of reading pre-war Yiddish literature in the post-war reality.17 This perspective was especially strongly manifested in the literary works read by survivors. A few decades later, some of the sketches for the illustrations for Reisen’s stories became a part of the collection of the Jewish Historical Institute (JHI), where they were given descriptive titles by the curators of the Art Department, since at the time when they were handed over by the inheritors, their provenance was unknown. Thanks to the information found in the archival collection left by Ernestyna Sandel, one of the first curators at JHI, it was possible to establish the provenance of some of the drawings and identify them as the illustrations for Reisen’s stories.18

A Jew Who Destroyed the Temple?19

Reisen’s story Der yid vos hot khorev gemakht dem templ [The Jew Who Destroyed the Temple] was published for the first time in the book Niu-Jorker nowełn [New York Short Stories] which came out in 1929.20 Although its text focuses on the contemporary issues concerning assimilation, an effect of living in the diaspora among Christians, its title carries the reader back to the ancient history of the Jewish nation. The title and the narrative of the story make references to different contents. It can be interpreted allegorically. The metaphorical title most likely refers to Jesus of Nazareth, and on a broader scale—to Christianity, which having been constructed on the foundation of Judaism, in a way destroyed the former order.

The destruction of the Second Temple of Jerusalem under the Emperor Titus Flavius in 70 A.D., resulted in the dispersion of Jews throughout the whole world of those times. As a consequence of the destruction of the Temple, Jews, having been ordered to leave Jerusalem, stopped the practice of offering sacrifices. It was replaced by prayer. Biblicists indicate that the final split between Judaism and Christianity did not happen until Christians started admitting into their ranks both pagans and Jews on the same terms.21 The faction of Judeo-Christians still advised compliance with the rules set forth in the Torah, with a particular recommendation to observe the Shabbat and the obligation to circumcise the Christians of pagan origin (Acts 15,1). During the Council of Jerusalem it was eventually agreed however that in the bosom of the Church the salvation of the faithful of Jewish and pagan descent could only depend upon the mercy of Jesus.22 For Jews, equating their status with the status of pagans was unacceptable.

In Judaism, the very act of saying a prayer, which replaced sacrifice offerings at the Jerusalem Temple, is a reminder of the Temple’s destruction. In the story we can hear an echo of a dispute as to whether in the reality of the contemporary diaspora, the titular temple is more of a synagogue or the American temple destined for Christians of different religious observances. The metaphorical destruction of the temple can be seen in the attempts to efface the difference between the (S-)synagogue and (Ch-)church, in both architectonic and theological senses. At the end, it is no longer clear if the one who destroys the temple is a traditional orthodox Jew praying in a modern American temple, or whether these are perhaps the assimilated Jews who have drifted away from orthodoxy. In the finale, the author of the story depicts with much humor the revival of the operating principles of a traditional synagogue in a Jewish-American temple which, having returned to its roots, succeeded in defending its distinctive character.

Isaac Celnikier’s pen and ink drawing for the story is a freely improvised portrait of a man, rendered with contrasting lines. The delicate depiction of the figure itself differs in its intensity from the expressive ink patches which accentuate mainly the objects of religious worship. The older, bearded man holds down a tallit thrown over his shoulders, it is recognizable by its characteristic dark stripes. The artist has suggested the presence of a tefillin on his forehead. With a focused expression on his face, the man might be preparing for prayer—the equivalent of the sacrifice offered in the Temple in the past. At the same time, we read the title of the drawing and nothing makes sense anymore. A Jew Der yid vos hot khorev gemakht dem templ? [The Jew Who Destroyed the Temple?]. The image and the title seem to contradict each other, just like the contrasting lines of the drawing, applied with different intensity. In that sense Reisen and Celnikier are coherent: there is a dissonance between the title and the contents, both in the storyline and in the image. Why would a religious Jew destroy a temple? The presented figure obviously refers us to the past, but how distant is this past?

Izaak Celnikier, illustration for Abraham Reisen’s story “Der yid vos hot khorev gemakht dem templ” [The Jew Who Destroyed the Temple] (current title: “Portret starego Żyda” [Portrait of an Old Jew]), 23 × 24 cm, pen and ink on paper, 1957, inv. no. MŻIH A-1576/6, Żydowski Instytut Historyczny im. Emanuela Ringelbluma, Warszawa [The Emanuel Ringelblum Jewish Historical Institute, Warsaw].

When we juxtapose the title of the story with the image of the man in Celnikier’s sketch, it brings up associations with the ancient times. Nevertheless, the drawing may also refer the viewer to the more recent historical events. The portrayed man, dressed like a religious Jew from the Polish interwar period (1918-1939), appears uncomfortable, even awkward. He uses the tallit to cover his naked, tormented body. The circles under the man’s cast down eyes, accentuated by the artist, attest to the ordeal he has been put through. Some elements are obviously missing. The other tefillin box is out of view, and the man holds down his left arm, as if he was trying to feel the empty spot once occupied by the absent element.

Although he is getting ready to pray, he asks himself a question: Is praying still possible after what we have gone through as a nation and after what I have gone through as an individual? The man overwhelmingly feels a break from the continuity of tradition, brought on by the tragedy of the Shoah. The sense involving the Holocaust can undoubtedly be contributed to an artist who survived World War II in dramatic circumstances. Thus, in such a reading of the drawing, the devastation of the temple would mean the annihilation of the Jews, committed by the Nazis, who, in accounts of the war, were called neopagans.

Two or Three Mothers?

Di tsvey muters [The Two Mothers] is the title of a cruel story written by Abraham Reisen in 1916.23 The story is told from the perspective of a man, whose wife Chana was taken to a psychiatric hospital. As the story unfolds, it turns out that the woman lost her first child, and in her present condition it seems to her that Leybele, her little son, is still alive. The sequence of the events that follow make us familiar with the methods used in psychiatry at the beginning of the 20th century. Following a doctor’s advice, the husband brings their neighbors’ child to the hospital, and the mother unambiguously identifies him as her dead son. Moreover, a moment later Chana comes up with an idea that is as cruel as the one that the doctor conceived. There is another woman on the ward, also grief-stricken after losing her son. Chana brings the boy she had affirmed as her child over to the woman, trying to convince her that she is the mother. While doing so, she keeps repeating: “She’s a madwoman, poor thing” and addresses her words to her husband.24 Has she managed to infiltrate the plan of the doctor who did not want to deprive her of illusions? In the story there is the barely suggested presence of an insightful madwoman who, in her own way, makes the other actors of the drama realize that she won’t let herself be deceived. The woman regains her peace of mind only after she discovers the fact that “her son” can bring relief to others who suffer. Apparently, nobody in these times took the boy’s feelings into consideration when he was told that he had three mothers instead of one. But for the actors of the drama it must have been of no importance.

So many questions arise when we look at the intimate scene of closeness between the woman and child drawn by Isaac Celnikier during the last year of his life in Poland, before he emigrated to Paris and settled there permanently. Who is this woman and what is her relationship with the child leaning against her knees? Why was he sketched out with an intense, varied stroke, in contrast to the hasty and vigorous drawing of the woman? Why does the child, despite his physical closeness with the mother, give the impression of a separate being? And finally: is he alive at all? The woman points to the boy’s heart with her hand. Beams radiate from her forefinger in all directions. Has she breathed in new life into him, or perhaps she has given up hers for him so that he might live? The artist has caught her moving her head as if she were waking up from a deep dream at the moment she passes on life-giving energy to the boy. How long has she been in lethargy?

Izaak Celnikier, illustration for Abraham Reisen’s story “Di tsvey muters” [The Two Mothers] (current title: “Kobieta z dzieckiem” [A Woman with a Child]), 22.5 × 24.5 cm, pen and ink on paper. 1957, inv. no. MŻIH A-1576/19, Żydowski Instytut Historyczny im. Emanuela Ringelbluma, Warszawa [The Emanuel Ringelblum Jewish Historical Institute, Warsaw].

Celnikier captured the boy in an abstract manner, as a barely present figure looking into the distance and resembling a doll-like object that someone has breathed life into. This concept of motherhood, in which physical closeness is accompanied by a certain lack of connection, was something that had been bothering Celnikier, as it reminded him of a specific image from the Bialystok ghetto where he lived during the occupation. The image of a mother caught in a sitting position with a child is a recurring motif of the painting Getto z aniołem [Ghetto with the Angel], on which the artist started working shortly after his arrival in Paris in 1958, one year after he had made the illustrations for Reisen’s story. Although the features of the women’s faces are somewhat different in these two realizations, Celnikier refers to the same prototype. The defenselessness of Celnikier’s heroine—who, in her insanity, shows humanity expressing itself in empathy for others who have experienced the trauma of losing a child—triggered in the artist an image from the reality of the ghetto.

Four Heroes

Di fir Heldn [The Four Heroes] is the title of Abraham Reisen’s short story, written in 1915.25 Not long before that, over 4 million soldiers were called up into the army in France, following the outbreak of World War I.26 It might have not been a coincidence that this was also the time when Reisen decided to emigrate from Poland to America.27 Presumably the pacifistic tone of the story stemmed from the writer’s own convictions. The narrative has the form of a draft, resembling reportage. It seems to be a commentary written in reaction to ongoing events which the author knew about from English-language press. On November 27, 1914, in London, Feiner Brockway and Clifford Allen founded the No-Conscription Fellowship. The first National Congress of the Fellowship took place on November 27, 1915, marking the first anniversary of its inauguration. The members of the organization often ended up in jail for their anti-war activity. It is very likely that Reisen wrote the story upon hearing the news about the founding of the Fellowship, wanting to honor its members.

The text includes reflections on the essence of heroic death. The author asks: Is a hero the one who, in the name of the idea of the brotherhood of nations, refuses to fight, because “many of them had their loved ones among the nations against whom they were ordered to fight.”28 Or is it the one who puts his life at stake for the sake of the nation he fights for, and therefore saves “the flag which has almost fallen into the hands of the enemy”?29 The first interpretation refers to the attitude of individual resistance; heroism is based on standing alone in opposition, in the name of the idea of the equality of all people and their right to live in peace. Only four individuals out of four million found enough courage to protest against mass conscription. They were not driven by the fear of death—their remonstration could have cost them their lives too. Paradoxically, the refusal to fight was interpreted here as an active act of resistance and heroism, whereas participation in the fight—in other cases identified with heroism—was equated with passivity and subordination, or even acting against oneself (“4 million soldiers of the same army that those four individuals did not want to join, did not want the war either. (…). Why weren’t we heroes like them?”).30

The passivity of those four million ready to fight was emphasized by comparing the soldiers to silent sheep: “Out of all 4 million soldiers, who remained silent like sheep, only those four spoke out: ‘We don’t want war! We don’t want to help you!’.”31 It is emblematic that the author uses sheep to build a metaphor for herd passivity. The difference between “they were silent like sheep” and “they went like sheep to slaughter” is not great, provided that both of these expressions are used with reference to the war.

Yael S. Feldman sets the concept of a martyr-sheep against a concept of a victim-sheep.32 The first refers to death suffered in the name of a higher idea, yet, voluntarily, and it is expressed in the Biblical quote: “accounted as sheep for the slaughter.” The idea of a noble death by unconstrained choice, death suffered in the name of God, stems from the Biblical sacrifice of Isaac. It was elaborated in more detail in Psalm 44, 17-23, depicting a man’s vulnerability in the fight in which there is no God: “All this has come upon us / But we have not forgotten You / Nor have we dealt falsely with Your covenant / Our heart has not turned back / Nor have our steps departed from Your way / But You have severely broken us in the place of jackals / And covered us with the shadow of death. (…) / Yet for Your sake we are killed all day long / We are accounted as sheep for the slaughter.”33 The psalmist talks about the innocent suffering that his nation has endured because of its belief in one God. Death like this is reflected in the concept of Jewish martyrdom by choice (kiddush hashem).

The concept of a martyr-sheep, which according to Feldman derives from the modern transformation of the Biblical phrase, is a different story. The term “We should not be led as sheep to the slaughter” was already used at the beginning of the 20th century as an emancipation slogan by Jews living in Palestine under British mandate, but it has become best known as a quote from the speech that a young partisan Abba Kovner delivered to the delegates of youth organizations in the Vilnius ghetto on December 13, 1941. Paradoxically, after World War II, the phrase with which Kovner exhorted his comrades to undertake armed resistance against Germans, encouraged blaming the victims of the Shoah as those who passively walked to their death like “sheep led to slaughter.” The transformation of the Biblical quote from: “Accounted as sheep for the slaughter” into: “Let us not be as sheep led to slaughter,” gave this concept of a victim the features of passivity. After World War II, it contributed to the dissemination of an anti-Semitic image of Jews as the passive, obedient ones, who did not have courage to fight back.

In 1998 Yehuda Bauer was still opposed to the idea of exploiting the likening of Jews-victims of the Holocaust to sheep led to the slaughter, claiming that no one besides the community of the victims has a moral right to use it and transform it for their own purposes.34 In this context, the story is a medium of the dispute between the idea of a martyr’s death for faith—kiddush hashem (expressed in the story through the belief in freedom of nations and peace between them)—and the topos of allegiance, which is turned here into passivity, tantamount to obeying orders.

Probably in 1957, the year when Reisen’s Oysgeveylte verk [Selected Works] was published by “Yiddish Bukh,” Celnikier made two sketches for the story. In the end however, he decided to use just one of them, which was eventually published in the book. Between the time the artist created the first and the second sketch, his own biography, and in particular, his experience of total war, had become a crucial point of reference for him. A story about World War I will become a prefiguration of World War II, the war which he survived.

Presumably, the drawing which was created first was the one that the JHI curators provisionally titled Leżące ciała martwych ludzi [Lying Bodies of Dead People]. It presents four dead figures lying on top of one another. All the lying bodies have the same orientation; their heads are placed on the left side of the drawing, not far from one another. It is difficult to match all the pairs of arms and legs with their owners, but Celnikier rendered the shape of the faces and the facial features with relative precision. Two of the figures at the bottom of the heap lie down on their backs with their heads turned up; thus, as viewers, we can recognize their profiles; the remaining two are lying on their sides, one of their faces is turned towards the viewer, the other one is seen from the top of their head in a left three-quarter view. It appears that the bodies of the dead people remain in relation with one another, the figures lying on their backs seem to embrace those who lie underneath them with tenderness. Although their sex has not been defined in any way, we could mistake two of the people sketched in the far left of the drawing for a pair of resting lovers, or men bearing resemblance to the ones described by Martha Beatrice Webb, who took part in the meeting of the No-Conscription Fellowship, and who depicted them as ”the intellectual pietists, slender in figure, delicate in feature and complexion.”35

Izaak Celnikier, illustration for Abraham Reisen’s story “Di fir Heldn” [The Four Heroes] – sketch no. 1 (current title “Leżące ciała martwych ludzi” [Lying Bodies of Dead People]), 21 x 43 cm, pen and ink on paper, 1957, inv. no. MŻIH A-1576/36, Żydowski Instytut Historyczny im. Emanuela Ringelbluma, Warszawa [The Emanuel Ringelblum Jewish Historical Institute, Warsaw].

A man with his face turned up has clenched eyelids and slightly parted lips which breath their last breath; frozen in an agonizing grimace. The person who lies beneath him rests the top of his head on the man’s chin; curled up and sunk lifelessly on the other participants of the drama. The lower and the central parts of the drawing are marked with stronger patches of ink, it might be a shadow cast by the pile of the bodies or a blood stain. The pronounced ink line is sometimes used to emphasize the contour of the faces and particular parts of figures’ bodies. Celnikier therefore sets the boundaries of their corporeality, although in doing so, he calls our attention to its deformation. The viewer might rack his brain trying to figure out why the man with the distinct facial contour has his toes braced against the earth, even though he is lying on his back. Likewise, it would be difficult for us to determine whose legs are sticking out in the foreground, in the central part of the depiction, at the bottom. Despite these questions, what we see here is the death of four individuals, not of a mass, since their faces are still clearly visible. One of the figures presented looks directly at the viewer, which can be interpreted as a gesture restoring individuality to the victims and connecting them with the viewer. The depiction is not drastic and that is probably how the artist himself viewed it, and so he went on to search further.

One of the elements that Celnikier embarks on in his first sketch, and which he elaborates on in the second, is a raised hand. In the first drawing, the hand disappears among other body parts and it is of minor significance to the composition as a whole, despite the artist’s attempts to emphasize it with multiple black ink lines. It is different when it comes to the second drawing, provisionally titled Kompozycja – scena z obozu – stos martwych ciał [Composition—Scene from the Camp—A Pile of Dead Bodies], which was eventually used in the book. He gives up on the order that he opted for in the case of the first sketch: the faces are no longer clustered together, the bodies are not lying in the same orientation, and the contours of the figures are hardly distinguishable. Above the entire composition, on the right side, a hand is raised in a dramatic gesture. There are three heads visible in the drawing: we can most clearly see a man on the left side of the composition, his face turned up. The male figure in the middle is undoubtedly an elaboration of the same centrally placed figure from the first drawing, which can be recognized by the bent head and an arm tossed over it. His facial features are deformed, and he stretches out in a convulsive gesture across the bodies lying underneath him. It is this person’s other hand, marked with a dark spot, which rises up and rests on a circular object that suggests the presence of the last head, shown from the back. The presence of the fourth person is just barely suggested: we notice it only because of a pair of legs visible on the right side of the composition. Yet looking for the torso or the face would only prove futile.

Izaak Celnikier, illustration for Abraham Reisen’s story “Di fir Heldn” [The Four Heroes] –sketch no. 2 (current title “Kompozycja – scena z obozu – stos martwych ciał” [Composition–A Scene from the Camp–A Pile of Dead Bodies]), 22 x 43 cm, pen and ink on paper, 1957, inv. no. MŻIH A-1576/35, Żydowski Instytut Historyczny im. Emanuela Ringelbluma, Warszawa [The Emanuel Ringelblum Jewish Historical Institute, Warsaw].

The second drawing shows the death of nameless victims rather than individuals to a much greater extent. In juxtaposition with the contents of the story, this is the drawing that builds a striking contrast: the four heroes are illustrated through a metaphor of decomposing and indistinguishable bodies, positioned in a manner which does not respect their dignity. As far as the first drawing is concerned, we can see that there was an effort to place the faces side by side. Here however, the bodies have been desecrated. Does Celnikier visualize the death of the four heroes, or of the rest of the four million soldiers, whose death in World War I was imminent? While drawing the first composition he tries to give back the martyrs their dignity, and yet he realizes that each one of those nameless victims of both World War I and World War II also had the right to die an honorable death, but none of them was given such a chance. Carrying the memory of the pile of corpses, underneath which he himself managed to hide at the end of the war in the suburbs of Dachau, and thanks to which he survived, he filters Reisen’s story through his own experience, and in consequence, captures the reality of war victims, fraught with convulsions.

These personal recollections must have been triggered by the piercing sentences in Reisen’s story, and though they could be applied to both world wars, the artist could only associate it with the post-war discourse about the Holocaust: “May their names be blessed forever… But their names were not known”; “They were silent like sheep,” or finally: “Why weren’t we heroes like them?”—a question that triggered a painful feeling in the artist, one that is characteristic of Holocaust survivors: a sense of guilt towards those who did not get the chance to survive. As Katarzyna Prot-Klinger writes, referring to William G. Niederland’s studies, the survivors’ sense of guilt stems from their identification with their beloved dead, and they unconsciously view their own salvation as a betrayal of their loved ones36. In the case of Celnikier, that feeling was most certainly intensified by the fact that he was accused of treason, on no legal grounds, by an NKVD (Soviet Security Service) officer during an interrogation in the Czechoslovakian town of České Budějovice37.The artist also expressed his feelings in his polemic against Paolo Ricci, in which he indirectly calls himself a representative of those who “have outlived” their own nation38. In this context, the question that Yehuda Bauer posed during the speech he delivered in the Bundestag in 1999, asking if those whom we call survivors have in fact survived, resonates intensely39.

In the course of his work on the illustration for Di fir Heldn [The Four Heroes], the artist gave up attempts at glorifying death. Instead, he emphasized its senselessness. He projected his own experience onto the story of World War I. The reportage-like, sketchy form of the story, inhibiting readers from identifying themselves with the participants of the action, was enriched by Celnikier with his own experience. It reflected itself in the creative process that took place between his work on the first drawing and the second.

The turning point at which the artist again took up the theme of the Shoah was the period of political “thaw” and his involvement in the Arsenal exhibition at that time. This is when he resumed the theme of the ghetto on which he had begun to work as a student in Filla’s studio in 1949. By placing the character of Isaac in the image’s composition—being an embodiment of both the artist himself and the Biblical figure of a sacrifice—he allowed himself to identify with his past again. The broken connection to Jewish culture during the socialist realist period returned anew in the time preceding Celnikier’s final departure from the country, at the time he received the offer from the “Yiddish Bukh” publishing house. To the artist and Holocaust survivor, the post-war reading of the pre-war stories, written by one of the epigones of Yiddish literature, became an incentive for confrontation with painful memories. Until his death in Paris in 2011, working through traumatic experiences continued to be an important feature of Isaac Celnikier’s artistic expression.

Translated by Dorota Liliental

Bibliography

Bauer, Yehuda. Przemyśleć Zagładę. Translated by Jerzy Giebułtowski and Janusz Surewicz. Warsaw: Żydowski Instytut Historyczny, 2016.

Benesz-Goldfinger, Zuzanna. “Czterej bohaterowie.” https://www.jhi.pl/blog/2020-03-16-czterej-bohaterowie.

— “Dwie czy trzy matki?” https://www.jhi.pl/blog/2019-04-29-dwie-czy-trzy-matki.

— “Żyd, który zburzył świątynię?” http://www.jhi.pl/blog/2019-12-09-zyd-ktory-zburzyl-swiatynie.

Celnikier, Isaac. “Rzeczy główne i odpowiedź Paolo Ricciemu.” Przegląd Kulturalny, September 15-21, 1955.

Chrostowski, Waldemar. Między Synagogą a Kościołem. Dzieje św. Pawła. Cracow, Apostolicum, 2015.

Isaac Celnikier. Registres de Vie. Paris: Société Historique et Littéraire Polonaise Bibliothèque Polonaise de Paris, 2018.

Feldman, Yael. S. “Not as Sheep Led to Slaughter? On Trauma, Selective Memory, and the Making of Historical Consciousness.” Jewish Social Studies: History, Culture, Society, no. 3 (Spring/Summer 2013): 139-169.

Fuks, Marian. S.v. “Abraham Rajzen.” Polski Słownik Judaistyczny. https://www.jhi.pl/psj/Rajzen_(Reisen)_Abraham.

Gilbert, Martin. Pierwsza wojna światowa. Translated by Stefan Amsterdamski. Poznan: Zysk i S-ka, 2003.

Guze, Joanna. “O Festiwalu Młodzieży.” Przegląd Kulturalny August 4-10, 1955.

LaCapra, Dominick. Representing the Holocaust. History, Theory, Trauma. Ithaca and London: Cornell University Press, 1994.

Lachowski, Marcin. “Getto w obrazach Marka Oberländera i Izaaka Celnikiera,” Ikonotheka no. 20 (2007): 39-52.

— Nowocześni po katastrofie. Sztuka w Polsce w latach 1945-1960. Lublin: Wydawnictwo KUL, 2013.

Leszczyńska-Cyganik, Barbara, and Joanna Boniecka, eds. Isaac Celnikier. Malarstwo, rysunek, grafika, exh. cat., Cracow: Muzeum Narodowe w Krakowie, 2005.

Lewin, Aleksander. Collection. Folder: Isaac Celnikier’s (Izaak Celnikier). Muzeum Warszawy, pracownia Korczakianum.

— Korczak znany i nieznany. Warsaw: Wyższa Szkoła Pedagogiczna Związku Nauczycielstwa Polskiego, 1999.

Nowak, Katarzyna. “Fragmenty mojej tożsamości. Rozmowa z Izaakiem Celnikierem.” Pro Memoria, no. 1 (2008): 28.

Pecaric, Rabbi Sacha, ed. Siddur Polish and Hebrew Pardes Lauder. Cracow: Fundacja Ronalda S. Laudera, 2005.

Pismo Święte Starego i Nowego Testamentu. Translated and edited by the Association of Polish Biblical Scholars at the initiative of The Society of Saint Paul. Częstochowa: Edycja Świętego Pawła, 2011.

Prot-Klinger, Katarzyna. “Życie po Zagładzie. Skutki traumy u ocalałych z Holocaustu. Świadectwa z Polski i Rumunii.” In Monografie psychiatryczne, vol. 9. Warsaw: Instytut Psychiatrii i Neurologii, 2009.

“Psalm 44.” The Holy Bible. https://enduringword.com/bible-commentary/psalm-44.

Puszkin, Barbara, ed. Żywa pamięć. W 75 rocznicę otwarcia Domu Sierot przy ulicy Krochmalnej 92. Materiały ze spotkania wychowanków Domu Sierot w dniu 18 maja 1988 roku. Warsaw: Międzynarodowe Stowarzyszenie im. Janusza Korczaka, 1989.

Reisen, Abraham. Oysgeveylte verk, vol. II, edited by Szoel Ferdman. Warsaw: Idisz Buch, 1957.

Ricci, Paolo. “Młode ‘stare’ malarstwo.” Przegląd Kulturalny, no. 35, 1955.

Roback, Abraham Aaron. The Story of Yiddish Literature. New York: Yiddish Scientific Institute–American Branch, 1940.

Ruta, Magdalena, ed. Nusech Pojln. Studia z dziejów kultury jidysz w powojennej Polsce. Cracow and Budapest: Austeria, 2008.

Sandel, Józef. “O Ogólnopolskiej Wystawie Młodych.” Fołks Sztyme, August 13, 1955.

Słucki, Salomon. Abraham Reisen–bibliography. New York: The Library and Archives of the Jewish Teachers Seminary and Peoples University, 1956.

Smith, Angela, ed. Women’s Writing of the First World War: An Anthology. Manchester: University Press, 2000.

Documents analyzed

Archives of the International Tracing Service in Bad Arolsen, Germany, on Isaac Celnikier’s life during the occupation, file no. T/D-818353, doc. nos. 5157935, 5157939, 82019146,82019148, 82019152, 82019158, 82019163, file no. T/D-818353, doc. nos. 78819462, 78819467.

Żydowski Instytut Historyczny im. Emanuela Ringelbluma [The Emanuel Ringelblum Jewish Historical Institute], Art Department Archive. Sandel, Ernestyna. Collection. Lexicon of Jewish Visual Artists whose last names start with “C.” File no. 44.

- A quote from Isaac Celnikier’s letter to Aleksaner Lewin “Szura” from September 14, 1992., ms. Aleksander Lewin’s Collection. Isaac Celnikier’s Folder, Muzeum Warszawy, pracownia Korczakianum [Museum of Warsaw, Korczakianum Research Lab]. ↩︎

- Abraham Reisen, Oysgeveylte verk [Selected Works], vol. II, ed. Szoel Ferdman (Warsaw: Idisz Buch, 1957). ↩︎

- A quote from Isaac Celnikier’s letter to Aleksander Lewin from September 14, 1992, ms. ↩︎

- Katarzyna Nowak, “Fragmenty mojej tożsamości. Rozmowa z Izaakiem Celnikierem” [Fragments of My Identity. A Conversation with Isaac Celnikier], Pro Memoria, no. 1 (2008): 69. ↩︎

- Nowak, “Fragmenty mojej tożsamości.” ↩︎

- Isaac Celnikier. Registres de Vie [Isaac Celnikier. Records of Life] (Paris: Société Historique et Littéraire Polonaise Bibliothèque Polonaise de Paris 2018), 8. ↩︎

- Dominick LaCapra, Representing the Holocaust. History, Theory, Trauma (Ithaca–London: Cornell University Press, 1994), 23. ↩︎

- LaCapra, 23. ↩︎

- Roman Kołoniecki, Powrót na Stare Miasto [Return to the Old Town] (Warsaw: Czytelnik, 1953); Andrzej Mandalian, Płomienie [Flames] (Warsaw: Ministerstwo Obrony Narodowej, 1954); Konrad Bielski, 38 równoleżnik [The 38th Parallel] (Warsaw: Czytelnik, 1954). ↩︎

- Paolo Ricci, “Młode ‘stare’ malarstwo” [Young “Old” Painting], Przegląd Kulturalny, September 1-7, 1955, 4. ↩︎

- Izaak Celnikier, “Rzeczy główne i odpowiedź Paolo Ricciemu” [General Matters and a Reply to Paolo Ricci], Przegląd Kulturalny, September 15-21, 1955, 3. ↩︎

- See Przegląd Artystyczny, March-April, 1955, 141. A critique from Ogólnopolska Wystawa Młodej Plastyki was also written by Józef Sandel in Folks Sztyme, August 13, (1955): 5. ↩︎

- Marcin Lachowski, “Getto w obrazach Marka Oberländera i Izaaka Celnikiera” [The Ghetto in the Paintings of Marek Oberländer and Isaac Celnikier], Ikonotheka, no. 20 (2007): 37–50. ↩︎

- Lachowski, “Getto w obrazach,” 37-50. ↩︎

- Joanna Nalewajko-Kulikov, “Kilka uwag o wydawnictwie Idisz Buch” [A Few Remarks about the Yiddish Bukh Publishing House], in Nusech Pojln. Studia z dziejów kultury jidysz w powojennej Polsce [Nusech Pojln. Studies in the History of Yiddish Culture in Post-War Poland], ed. Magdalena Ruta (Cracow–Budapest: Austeria, 2008), 129. ↩︎

- Nalewajko-Kulikov, “Kilka uwag o wydawnictwie Idisz Buch,” 132. ↩︎

- Eugenia Prokop-Janiec, Literatura i kultura jidysz w publikacjach polskich okresu PRL [Yiddish Literature and Culture in Polish Publications in the Period of the Polish People’s Republic], in Nusech Pojln, 318. ↩︎

- S.v., “Celnikier Izaak,” in Spuścizna Ernestyny Sandel. Leksykon. Hasła artystów plastyków Żydów na literę “C” [Ernestyna Sandel’s Collection. Lexicon of Jewish Visual Artists whose last names start with “C”], The Emanuel Ringelblum Jewish Historical Institute (ŻIH), Art Department, Folder no. 44, 2. ↩︎

- Abraham Reisen, Oysgeveylte verk, 326–329. The story translated into Polish by Magdalena Wójcik can be found on the website: http://www.jhi.pl/blog/2019-12-09-zyd-ktory-zburzyl-swiatynie, (accessed: 4.21.2020). ↩︎

- S.v., “Abraham Rajzen” (Abraham Reisen) in ŻIH Polish Judaic Dictionary, https://www.jhi.pl/psj/Rajzen_(Reisen)_Abraham, (accessed: 4.21.2020). ↩︎

- S.v. Waldemar Chrostowski, Między Synagogą a Kościołem. Dzieje św. Pawła [Between the Synagogue and the Church. The Story of St. Paul] (Cracow: Apostolicum, 2015), 137–149. ↩︎

- Chrostowski, Między synagogą a kościołem, 137-149. ↩︎

- Reisen, 115-119. The story translated into Polish by Magdalena Wójcik can be found on the website: https://www.jhi.pl/blog/2019-04-29-dwie-czy-trzy-matki (accessed: 4.21.2020). ↩︎

- Reisen, Oysgeveylte verk, 118. ↩︎

- Reisen, 121-123. The story translated into Polish by Magdalena Wójcik can be found on the website: https://www.jhi.pl/blog/2020-03-16-czterej-bohaterowie (accessed: 4.21.2020). ↩︎

- Martin Gilbert, Pierwsza wojna światowa [World War I], trans. Stefan Amsterdamski (Poznan: Zysk i S-ka, 2003), 62. ↩︎

- S.v. Abraham Aaron Roback, The Story of Yiddish Literature (New York: Yiddish Scientific Institute–American Branch, 1940), 209-214, 395–396. ↩︎

- Reisen, 122. ↩︎

- Reisen, 121. ↩︎

- Reisen, 122. ↩︎

- Reisen, 122. ↩︎

- Yael S. Feldman, “Not as Sheep Led to Slaughter? On Trauma, Selective Memory, and the Making of Historical Consciousness,” Jewish Social Studies: History, Culture, Society, 19, no. 3 (Spring/Summer 2013): 139–169. ↩︎

- “Psalm 44, 17-23” in The Holy Bible, https://enduringword.com/bible-commentary/psalm-44 (accessed 5.25.2020). ↩︎

- Feldman, 142. Yehuda Bauer elaborates on the subject of the Jewish resistance movement in his book Przemyśleć Zagładę [Rethinking the Holocaust], trans. Jerzy Giebułtowski and Janusz Surewicz (Warsaw: Żydowski Instytut Historyczny, 2016), 191. ↩︎

- Martha Beatrice Webb, “The No-Conscription Fellowship,” in Women’s Writing of the First World War: An Anthology, ed. Angela Smith (Manchester: Manchester University Press, 2000), 117–119. ↩︎

- William G. Niederland, “The Survivors Syndrome: Further Observations and Dimensions,” Journal of the American Psychoanalytic Association, no. 29 (1981): 413–425, cited after Katarzyna Prot-Klinger, “Życie po Zagładzie. Skutki traumy u ocalałych z Holocaustu. Świadectwa z Polski i Rumunii” [Life After the Holocaust. The Trauma Consequences of Holocaust Survivors from Poland and Romania], in Monografie psychiatryczne [Psychiatric Monographies], vol. 9 (Warsaw: Instytut Psychiatrii i Neurologii, 2009), 98. ↩︎

- Izaak Celnikier. Malarstwo, rysunek, grafika [Isaac Celnikier. Painting, Drawing, Graphics], exh. cat., eds. Barbara Leszczyńska-Cyganik, and Joanna Boniecka (Cracow: Muzeum Narodowe w Krakowie, 2005), 113. ↩︎

- Izaak Celnikier, “Rzeczy główne i odpowiedź Paolo Ricciemu”, 3. ↩︎

- Bauer, 340. ↩︎

Zuzanna Benesz-Goldfinger

Zuzanna Benesz-Goldfinger is a cultural anthropologist and an art historian, a collection keeper at The Emanuel Ringelblum Jewish Historical Institute’s Art Department, and a curator of exhibitions. Her interests include presentations of the human image in Jewish art, performativity, and affinities between literature, theology and art.