Tytuł

Gendered Representations of Beauty and the Female Body in Holocaust Art

https://www.doi.org/10.48285/8kaewzlo3p

https://miejsce.asp.waw.pl/english-gendered-representations-of-beauty-and-the-female-body-in-holocaust-art/

Abstrakt

Looking at Holocaust art through the lens of gender, this paper argues that there is a correlation between suspicion of the visual arts as a reliable form of Holocaust remembrance in the early decades after the war and the marginalization of women’s experiences. It considers representations of beauty and the female body in art from the ghettoes and camps, as well as art created by secondary witnesses during or shortly after the war. Despite the apparent collapse of aesthetic canons and value systems after the Shoah, conventional tropes and socially sanctioned norms of gender and sexuality tacitly shaped these Holocaust representations. On the other hand, increasing acceptance and even privileging of visual art’s capacity to represent the Holocaust since the 1990’s has coincided with the emergence of feminist perspectives in Holocaust studies and a growing interest in gender-specific experiences under extreme conditions. Thus, some of the more recent visual postmemorial forms reveal the potential of Holocaust art to challenge and transform traditional frameworks of meaning and stagnant conceptions of gender.

DOI

Until the mid-1990s, art inspired by the Holocaust elicited only limited interest, compared to other forms of representation, written testimonies in particular. The recent memory of visual aesthetics’ complicity in the propagation of the National Socialist Weltanschauung undoubtedly compounded a distrust of art’s ability to convey the immensity of the horror. It is worthy of note that this exclusion of visual art as a reliable medium of remembrance coincided with the marginalization of testimonies by women. As feminist Holocaust scholars have argued, dominant forms of Holocaust memory privileged male experiences, although they were coded as universal and gender-neutral.1 This paper traces correspondences between the liminal status of visual art and the exclusion of female testimony in early Holocaust remembrance, situating them in the context of hegemonic norms of gender and sexuality that tacitly shape and persevere in aesthetic representations. Conversely, as I show in the second part of the paper, a positive shift in the late 1990s in perceptions of art’s capacity to represent the Holocaust coincides, in terms of chronology as well as changing sensibility, with the emergence of feminist perspectives in Holocaust studies, and a growing interest in gender-specific experiences. Discussions about Holocaust art in the 1990s and onwards abandon a previous suspicion towards the visual arts and affirm the potential of imaginative forms.2 Thus they disclose that imagination—construed by philosophical aesthetics as the free faculty of the mind that operates without predetermined rules3— is imprinted with gendered scripts and frameworks of meaning. Despite both prolific feminist scholarship and interest in Holocaust art as a form of commemoration in recent decades, systematic studies of representations of gender in Holocaust art are still notably lacking.4 Debates about which representations should be privileged vehicles of Holocaust memory have also raised questions about the suitability of traditional aesthetic concepts to convey the reality of destruction. The ideal of beauty lies at the core of Western conceptions of art, culminating in G.W.F. Hegel’s pronouncement about art’s unique capacity to convey beauty because it reconciles the suprasensible ideas with the sensuous medium of expression.5 Holocaust art, however, has been afflicted by an injunction against beauty—lest it extracts enjoyment from unspeakable pain and dissolves horrors in pleasurable forms. Jewish American artist Barnett Newman, for instance, proclaimed, in 1948, that beauty was inconceivable in the wake of the war’s devastation and horror; as a result, “the impulse of modern art is the desire to destroy beauty.”6 Yet if we consider that within Western canons of representation beauty has generally been conceived as a feminine ideal,7 the interdiction against beauty in Holocaust art might also be read as implicitly directed against representations of the feminine. Perhaps, therefore, the post-Shoah interdiction against aestheticization is tacitly underwritten by a conventional politics of gender, while the indictment of beauty in the face of atrocity intersects with gendered scripts of violence, memory, and trauma.

Verschönerung: Representations of Beauty and the Female Body in Art from Camps and Ghettoes

Although very few female artists have been included in the early canon of Holocaust art,8 many women created works that presented the reality of the ghettos and camps. In Terezìn, for instance, besides Charlotte Burešová and Malvina Schalková, artists such as Zdenka Eismannová, Hilda Zadiková, Ernestina Kleinová and others produced images of everyday life in the ghetto, often focused on depictions of women in their dormitories, engaged in domestic chores such as food preparation, mending clothes, and cleaning up. These scenes of domesticity wrought under duress foregrounded mutual assistance, friendship and solidarity, a visual lexicon that mirrored women’s traditional roles and socialization process, as well as the need to rely on familiar cultural practices and norms to express a new and often incomprehensible reality. In earlier scholarship on Holocaust art, these works created by female artists were recognized primarily as documents of the time, depicting “the suffering of the most vulnerable victims.”9 Such a limited view of works created by female artists reflected essentialized conceptions of womanhood inherent in these interpretations; however, it also underplayed or effaced altogether their aesthetic qualities and artistic merit.The repertoire produced by female artists in Terezìn, imbued with grace and quietude, differs from the artworks by men, known for dramatic and anguished renditions of scenes of suffering and death. Dignified portrayals of inmates by Burešová, who saught to “oppose the disaster with beauty,”10 stand in contrast with dramatic, expressionist sketches by Bêdrich Fritta, Leo Haas, and Otto Ungar. Polish artist Zofia Stępień-Bator has been remembered for her “beautified” portrayal of Mala Zimetbaum, a legendary member of camp resistance; as Stępień-Bator later said of the drawings she made in Auschwitz, “the women were prettier, livelier, and all had more hair, there were no tragic expressions in their eyes.”11 Conversely, some of the artworks project anxiety over a loss of femininity. For instance Esther Lurie, a Jewish artist from Kovno, created images of vanishing female beauty in the clandestine sketches made during her imprisonment in Leibitz. The female figures in Lurie’s portraits are grotesquely tall, wearing oversized coats and large boots, their feminine features effaced. In one of the close-ups of prisoners’ faces, The Portrait of a Jewish Inmate—She Was Beautiful Once, a woman is wearing a headscarf and a broad-shouldered coat, her rectangular face and lips drawn downwards projecting an androgynous physiognomy.12 What all of these images convey is a yearning for feminine beauty, as this was paramount for female prisoners’ sense of identity and personal dignity. The loss of femininity became emblematic of the devastation and hopelessness of life in the camp.

Esther Lurie, “Portrait of a Jewish Inmate—She Was Beautiful Once”, 11.5 x 7.5 cm, pen and ink, 1944, The Ghetto Fighters’ House Museum Art Collection, item no. 820, courtesy of The Ghetto Fighters’ House Museum, Israel.

In interpretive essays in catalogues of exhibitions of art from camps and ghettoes, artworks by women are often juxtaposed with the drawings by male artists, and it is the latter that have become emblematic of authentic witness. The clandestine works of the male members of the Zeichenstube (graphics department) in Terezín were created for the most part in resistance to the Nazi Verschönerung (beautification) project, which was meant to deceive the Red Cross commission. Nazi officials at Terezìn ordered the artists to produce detailed, realistic depictions of positive aspects of the camp, which were then deployed to create a façade for propaganda purposes. Thus by using dramatic, expressionist forms, dubbed “degenerate art” by the Nazi regime, the artists also resisted conscription into the project of deception at the level of technique and style. In this context, art that merely depicted or beautified camp reality, art usually created by women, is implicitly coded as “less authentic” and acquiescent with the project of deception. In multiple senses, therefore, beauty and beautification, as they have been associated with women, the female body, and socially prescribed female pursuits, have become a veiled cipher for falsification of the harsh reality of camps and ghettoes, a connotation that weakens female artists’ testimonial credibility and undermines the artistic value of their work.

Eros/Thanatos and Sexualized Portrayals of Violated Female Bodies

The way socially sanctioned norms of gendered comportment shaped the iconography of Holocaust art produced in the camps and ghettoes is reflected in the twin motives of suffering, self-sacrificing mothers and violated, sexualized female bodies. In Western iconography, the motif of the mother trying to protect her children or grief-stricken by their loss has functioned as a quintessential trope of inexpressible suffering; it also frequently appeared in the works of both female and male Holocaust artists, many of whom likely witnessed similar scenes. This theme is prevalent, for instance, in hundreds of expressionistic drawings by Polish Jewish artist Halina Ołomucka, which convey the despair, emotional turmoil and physical agony witnessed by the artist in the Warsaw ghetto and in the series of camps to which she was deported. The emblematic image of the suffering mother is also prevalent in works by artists who were indirectly affected by Nazi persecution. Some of the best known of these works are Jacques Lipchitz’s dramatic sculpture Mother and Child (1941–42), and German artist Lea Grunding’s allegorical drawings made between 1942–44, which echo her predecessor Käthe Kollwitz’s expressionist style and iconography of mothers and children.13

Halina Ołomucka, “Mother and Child”, 21.1 × 13.6 cm, pencil on paper, 1945–47, USHMM collection, object no. 2001.122.83, courtesy of USHMM Museum.

While sacrosanct images of bereft mothers follow similar conventions in works by both male and female artists, depictions of violated female bodies are strikingly different. Female artists did not produce images that depicted or even alluded to rape, and relatively few left a pictorial record of various forms of sexualized violence experienced in the camps, such as public nudity, sexual taunting, and the shaving of hair. Moreover, compared to the scenes of domesticity and female solidarity, these disturbing images by female artists have been less frequently exhibited or reproduced in catalogues of Holocaust art and therefore remain relatively unknown. For instance the first panel in the album Témoignages [Testimonials] by Violette Lecoq, a French resistance fighter incarcerated in Ravensbrück, shows elegantly dressed women arriving at the camp, while the second panel, titled Deux hours après [Two Hours Later], depicts them with their heads shaved and their faces blank with the shock of this brutal transformation into dehumanised Zugänge (recently admitted prisoners).14 Ella Lieberman-Shiber’s drawing The Cutting-Off is a graphic rendition of the scene of shaving the heads of women arriving in Auschwitz, the women’s terrified faces shown in close-up. Although, unlike the works described in the previous section, these images depict violence, for these artists the shaving of the head is also emblematic of the loss of femininity as a measure of dehumanization in the camp.

Representations of female bodies in works by male artists, while very different, also follow inherently gendered conventions. In a rare example of an eyewitness pictorial record from the Janowska camp in Lvov, Zeev Porath’s (Wilhelm Ochs) drawing entitled Tortures depicts a scene of sadistic punishment being meted out against female inmates. We see a group of women lying naked on the ground, presumably dead; a dozen undressed women are standing at an Appell, and, in the foreground, a woman, hung upside-down from a wooden turnspit, is being lashed with a whip by a guard. While the drawing is intended as a compassionate act of witnessing, the artist draws the women’s bodies, particular their buttocks, as voluptuously shaped, revealing an element of voyeurism and a perseverance of the eroticized conventions of drawing female nudes, despite their incongruity with the horrific subject matter.

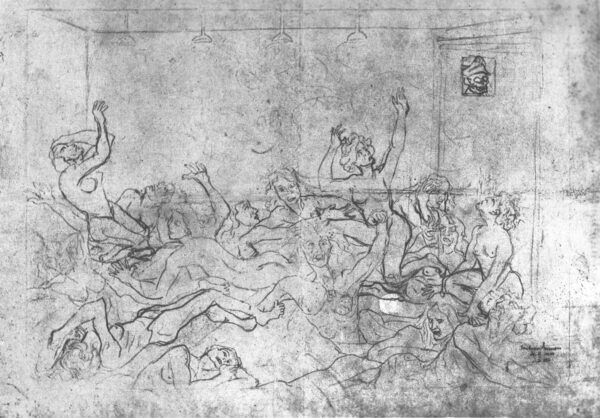

More explicit in this regard is Wiktor Simiński’s drawing In the Gas Chambers, which depicts an entangled mass of women at the moment of their agonizing death, sketched by the Polish artist shortly after his liberation from Sachsenhausen. The fulsome curves of the women’s bodies and their textured hair can be clearly discerned, while the expression on their faces oscillates between agony and ecstasy in the convention of Bernini’s Ecstasy of St. Teresa. A male guard is looking through a peephole, his leering grimace underscoring the image’s prurient undertones.

Wiktor Simiński, “In the Gas Chambers”, 35.5 × 60.9 cm, pencil on paper. 1944. Janina Jaworska Collection, Warsaw, photograph of the drawing courtesy of the USHMM collection.

Similar eroticized imagery pervades David Olère’s pictorial record of the French artist’s incarceration in Auschwitz, where he had been selected to work as a member of the Sonderkommando. Olère’s sketches convey the horrors of his gruesome work primarily through depictions of violated female bodies of extraordinary beauty. In A l’entrée de la chambre à gaz [At the Entry of the Gas Chamber] (1950), for instance, terrified naked women are standing in the exit of the undressing room; in La salle des fours du crématoire III [The Oven Room of Crematorium III] (1945), beautifully composed female corpses are dragged toward a crematorium oven; and in an untitled drawing from 1947, a dead woman’s body, arranged in a sexualized pose, is dissected by a male doctor who stands suggestively between her wide-open legs.15 While Simiński’s and Olère’s eroticized iconography is overt, a similar, sexualized motif of the naked female body appears in Pablo Picasso’s The Charnel House (1945), celebrated as a manifestation of the Spanish artist’s fierce protest against the horrors of the war: a protruding female breast is the punctum that gathers together the geometric patterns of this large canvas.16

While depictions of sexual violence do not appear in works by female artists, in men’s art, the theme of rape or the threat of rape has been frequently used to convey the scope of Nazi brutality. In Jean Fautrier’s Sarah-Hostage (1942), from the series Hostages (inspired by the artist’s experience of witnessing the execution of civilians), a female figure is sitting on the ground in a pose of sexual vulnerability, with one leg bent open to the side. Her pubic area and stomach are exposed and covered in raw strokes of black and red paint, alluding to rape and life-force atrocities on pregnant Jewish women. Similar iconography can be seen in paintings by Hyman Bloom, an American artist of Jewish-Latvian descent, which are based on iconic liberation photographs. Torso and Limbs (1952), for instance, depicts a female torso curved upwards, exposing breasts, while one leg, with a delicate, elongated foot, is thrown out to the side. Although the body is mutilated—the other leg and the woman’s head are severed from the torso, suggesting extreme violence—the body parts are arranged in a harmonious geometric composition which nevertheless suggests sexual violation. A similar aesthetics animates Bloom’s Female Cadaver (1953), in which, as in Olère’s drawings of medical experiments, the autopsied body is cut wide open from the sternum to the crotch and arranged in a sensuous pose of sexual submission.

Motifs of sexual violence against women have been embedded in the visual repertoire of Western art, with frequent allusions to the Roman legend of the rape of the Sabine women, the Greek myth of the rape of Europa, or the biblical motif of Susanna and the Elders. In Holocaust art, this traditional imagery of sexualized, violated female bodies appears in contrast to images of suffering mothers, a split iconography that uncannily replicates the conventional binary of the “mother/whore” stereotype.

“The Prostitute”

In contrast to images of martyred yet uncannily eroticized female bodies that represent victimization, the motif of “the prostitute” frequently appears in works by male artists as a signifier of Nazi evil. For instance a drawing by Abraham Ryza, an inmate in Lebenau camp, titled A Sunday Pastime of the SS: Setting the Dogs on an Inmate (1945), depicts a brutal act carried out seemingly for the amusement of three SS officers, who are shown standing to one side accompanied by two women clad in high-heeled shoes and short décolletaged dresses: accessories that likely identify them as “prostitutes.”17 A similar motif, though in the form of an allegory, appears in Bêdrich Fritta’s Fantasia (1943/44), in which the depravity of the war is represented as a nude woman whose provocative posture and high-heeled boots allude to her profession. Surrounded by a crowd of exhausted inmates, she is flaunting her military trophies: a medal pinned to her naked chest, a shako cap, and a saber by her side, which seems to be pointing at her pubis.18

The iconography of “the prostitute” is particularly striking in the work of artists who, although not eye-witnesses to events, were passionate observers, disturbed by the moral collapse wrought by the horrors of WWII. Mario Mafai’s Fantasia (1942), for instance, from a series of reflections on the war titled Fantasies of 1940–44, shows three nude female figures arranged in sensuous poses reminiscent of Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec’s drawings of Parisian sex workers. A Harlequin is leering at a woman who is lying on the ground with her knees raised and legs open; her hands are held by figures outside the frame of the painting, indicating the coercive nature of the pose. The intense red and orange hues imbue this grotesque commedia dell’arte with an aura of violent sexual passion. Mafai’s intense, sexually charged images of women stand in contrast with some other paintings from the series that depict violence against men. For instance, Fantasia 11 shows several undressed men, kneeling or lying on the ground with their hands bound behind their backs and their heads bent forward in a posture of dignified resignation; a silhouette of a soldier with a pointed gun indicates that this is a scene of execution.

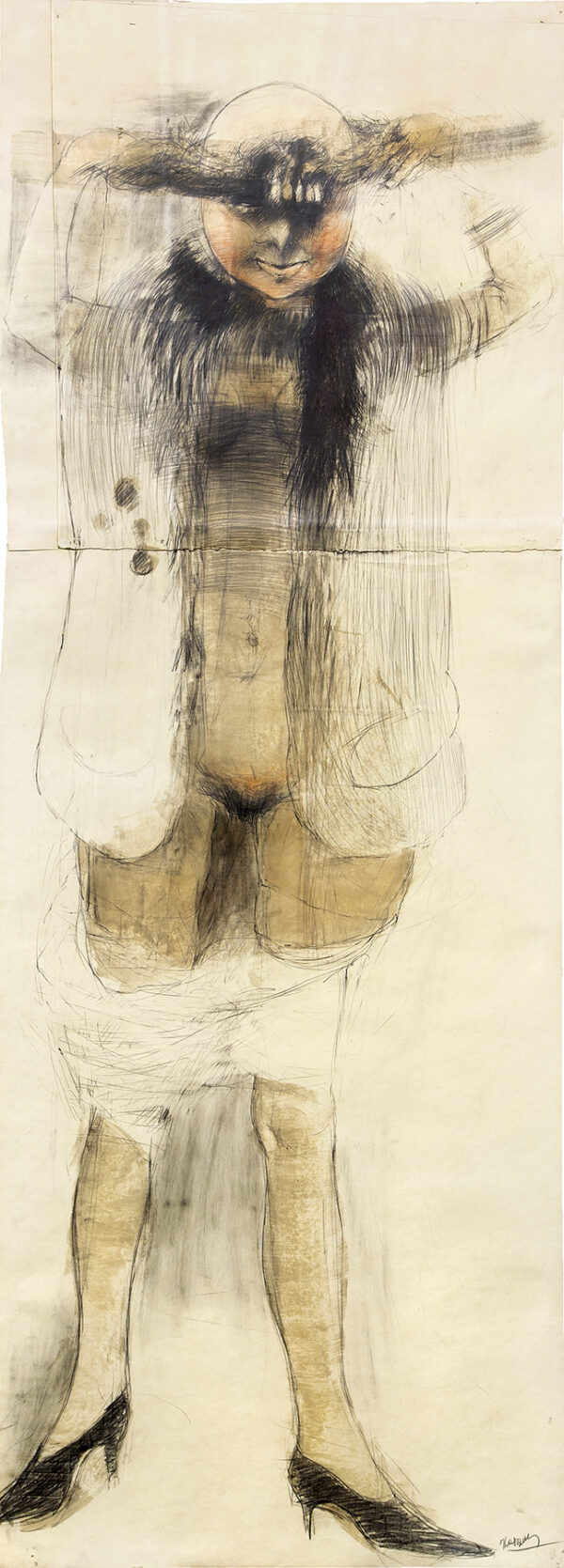

In post-war responses, “the prostitute” has been immortalised in The Nazi Drawings by Argentinian artist Maurizio Lasansky, the son of Jewish immigrants from Lithuania. In 1962, moved by the Eichmann trial, Lasansky began drawing a series of sketches centered around the figure of an allegorical Nazi. In the seventh panel of the series, “the prostitute” appears—she is naked, except for a pair of high-heeled shoes and a bonnet with a frill made out of teeth, an accessory that matches the detail on the visor of the Nazi’s skull-like helmet. In another panel, her underwear is obscenely pulled down, and she is depicted without a bonnet, revealing a bald head, likely an allusion to the punishment commonly given to women for “sleeping with the enemy.” Although her pubis is on full display, the bald figure appears to be androgynous: the female evil is defeminised, stripped of what is now unmasked as demonic, fake femininity. Other panels show Death-like characters, adorned with swastikas that indicate their Nazi affiliation, engaging in violent sex acts with “the prostitute,” to which she is submitting with a toothy grin. This pictorial mishandling of the female body is underscored by captions: for instance, panel #12, in which “the prostitute’s” body is being chewed and mangled in a violent caress, is accompanied by the text: “the prostitute is pathetically strung up like a side of beef.” In contrast, another striking panel in the series shows a naked male inmate with his skin flayed, the criss-crossed marks resembling the strap of a phylactery on his arm identifying him as Jewish. As the artist explained, the image was a reference to the members of the Sonderkommando.19 Their unwilling complicity with the Nazi evil is portrayed as torture, while their flayed epidermis might allude to the lampshades allegedly made from tattooed male skin by the “monstrous” Ilse Koch. The comparison with the figure of “the prostitute” is telling: as in Mafai’s paintings, the male figure in Lasansky’s drawing appears in a pose of crucifiction and martyrdom, in stark counterpoint to the woman who is shown as willingly participating in her own, ultimately fatal, assault by Death. As a visual commentary on the Eichmann trial, Lasansky’s disturbing portrayals of Nazi evil are a passionate rebuttal of Hannah Arendt’s thesis on the banality of evil. They reveal, however, unsettling contemporary sensibilities: viewers and critics who hailed The Nazi Drawings as a masterpiece unquestioningly accepted figurations of ultimate evil by way of images of brutal assaults on the female body.

Mauricio Lasansky, “Nazi Drawing No. 8”, panel no. 8. 175.2 × 58.4 cm, graphite, turpentine, and earth colors on paper, 1961–66, Lasansky Corporation Collection, courtesy of the Lasansky Corporation.

A somewhat different dynamic seems to be at work in pornographic images of women in the work of American artist Boris Lurie (born in Latvia), a survivor of Buchenwald. One of Lurie’s early works, entitled Saturation Painting (1959), features a well-known photograph of Buchenwald survivors, framed by a collage of pornographic pin-ups. Most likely, this startling composition is a commentary on a scopophilic impulse inherent in post-war audiences’ responses to liberation photographs circulating in mass media.20 Although Lurie’s work also relies on the exploitation of female bodies and as such has to be subjected to critical analysis, his use of such imagery also betrays a transferential dynamic on the part of the camp survivor who finds himself “feminized” by the spectators’ objectifying gaze. Thus, Lurie’s shocking juxtaposition of liberation photographs and pornographic images can be read as a metonymic expression of the survivor’s humiliation associated with a loss of masculinity in the camps and projected onto a sexualised female subject. While ostensibly critiquing mass consumption of images of atrocity, by recirculating pornographic snapshots Lurie is reclaiming the degraded image of a male survivor, restoring his vitality and sexual agency. At the same time, as the artist expressed in interviews, the powerful, negative affects exuded by his collages convey, perhaps perversly, the layers of unresolved grief precipitated by the murder of all the women in Lurie’s life: his mother, sister, grandmother and girlfriend perished in a mass execution near Riga in 1941.21 The ambiguities of affective vectors that animate Lurie’s work—compassion and voyeurism, mourning and desire—are underplayed in commentaries on this work because of his inviolable status as a survivor. Yet, perhaps one of the artist’s aims is to challenge that status and expose its limitations and vulnerabilities.

Inverting Gendered Paradigms/Reclaiming Sexual and Testimonial Agency

In Memory Effects: The Art of Secondary Witnessing (2002), Dora Apel argues that post-memorial artists’ explorations of the body and sexuality as sites of (re)constructing Holocaust memory are an effective strategy of approaching difficult subjects, especially those that have remained veiled in ambiguity, silence, and taboos. This section discusses the works of several contemporary Holocaust artists who have re-imagined the female body’s vulnerability, destruction and violation, but also its resilience, erotic power and agency.22

One exceptional case is Polish-Jewish sculptor Alina Szapocznikow, known for her monumental works that focussed on the body’s biological existence, its metamorphoses, vitality and decay. Szapocznikow survived the ghettos of Pabianice and Lodz, and then several camps, including Auschwitz-Birkenau and Terezìn.23 Unlike the survivors of the camps discussed earlier in this paper, Szapocznikow bracketed that experience, and only faint inscriptions can be gleaned from some of her works, such as the sculpture Ekshumowany [ Exhumed ] (1955), or the brass and granite molds of limbs and body parts: a female torso in Piękna Kobieta [A Beautiful Woman] (1956), Ręce I, Ręce II [Hands I, Hands II] (submitted for an Auschwitz monument competition in 1958), or Noga [Leg] (1965), all of which betray an intimacy with ruthless death. Yet even these works, although they look forlorn and bespeak the violence of bodily fragmentation, also project sensuousness, vulnerability and beauty.

The only direct references to the Nazi camps appear in Szapocznikow’s late works Wielkie Nowotwory (Grand Tumeurs), in which traumatic memory of the Holocaust blends with the documentation of the artist’s struggle with terminal cancer. The photographs of the female face and the liberation photographs of corpses (and hence a mediated rather than a personal visual recollection) appear side by side, sunken into the surface of huge blocks of artificial resin. The result is a unique fusion of temporal and corporeal landscapes: the imprints of a recent historical catastrophe and the singular history of the artist’s body meld into forms that are unsettling and even macabre, but also sensual, beautiful and erotic.

In focusing on the woman’s body as the site of vitality, agency, and pleasure despite its transience and inevitable decay, Szapocznikow’s art predates feminist interventions of the 1970s by American artists such as Carolee Schneeman, Judy Chicago, Kiki Smith, Cindy Sherman, and Hannah Wilke, who represent the female body as a fluid terrain on which to interrogate and dismantle conventional conceptions of beauty that have been predicated on objectification. Moreover, unlike the images of human flesh reduced to either macabre piles of corpses or fields of ashes, Szapocznikow enriches the post-Holocaust visual landscape with an apotheosis of the female body in its intimate, erotic materiality, intertwined with the flesh of the world, to draw on Maurice Marleau-Ponty’s evocative metaphor.

Szapocznikow’s work therefore anticipates changes in the understanding of gender-specific experiences and behaviours under extreme conditions, which were precipitated by the emergence of feminist perspectives in the mid-1980s and throughout the 1990s. This shift in perceptions of gender allowed Holocaust scholars and artists alike to break through taboo social constructs, especially those surrounding sexuality and sexual violence. For example we can compare Boris Lurie’s later work Untitled (Corset with a Star of David) (1982), a collage in which the artist alludes to a well known photograph from the 1941 pogrom in Lvov showing a terrified woman, dressed only in a white slip and garters, being chased down the street, with The Scream—Lvov 1941 (2008), by Rachel Roggel, an Israeli artist and daughter of Holocaust survivors. Roggel’s work, like Lurie’s, is a mixed-media collage, which features a white female undergarment draped on a red satin background and framed by black tulle.24 The artist explains, “At first glance, my works are decorative and inviting… giv[ing] an impression of a sexy adult scene on a stage.”25 On a closer look, however, we notice the outlines of screaming skulls floating on the surface of the deep-red fabric, while ghostly little hands seem to be tugging on the slip, perhaps an allusion to a young boy who, in the photograph from the Lvov pogrom, is shown running after the woman with a stick in his hand. The reference in the title of the work to Edvard Munch’s masterpiece reframes the Norwegian artist’s expression of existential anguish as the Jewish woman’s terrifying experience of sexual assault and imminent murder. Similarly to Lurie, Roggel incriminates viewers in the eroticized pleasure derived from the spectacle, and she reflects on the contemporary eroticization of atrocity. At the same time, the rich colors and multilayered texturing of her work metonymically transform the fetishized garment into a symbol of empowerment and testimonial agency, reclaiming the power of female beauty and intimacy.

Rachel Roggel, “The Scream—Lvov 1941”, 124 × 77 cm, mixed media with lingerie, tulle, satin, buttons and glass beads, 2008, collection of the artist, Israel, courtesy of Rachel Roggel. Photographer: Ran Erde.

Another second-generation artist, Haim Maor, describes himself as “a walking memorial candle,” his multi-media artworks indexing the wounds of his parents’ past.26 Female Nude with My Mother’s Face (1986-87) is an image of an undressed woman, bearing the face of his mother as a young girl, transposed onto a large wooden cross and frozen in a posture of shame, reminiscent of depictions of biblical Eve (for instance, in Lucas Cranach the Elder’s Adam and Eve). On both arms of the cross are his mother’s concentration camp mugshots, one in profile and the other facing forward, enclosed by dark semi-circles of either a halo or the spectral contour of a crematorium oven. Maor evokes the traditional iconography of the female nude to convey the motif of the loss of innocence but also the son’s anxiety about his mother’s possible sexual violation in the camp.27 Yet in this transgressive depiction of a mother as if standing “naked” before her son, the mother’s body is transformed into a luminescent figure of memory, reminiscent of a Byzantine icon or a painting on the cover of an ancient Egyptian coffin.

Haim Maor, “Female Nude with My Mother’s Face”, 200 × 150 cm, triptych, high gloss paint and lacquer on wood, 1986–87, collection of the artist, Israel, courtesy of Haim Maor.

The wooden background upon which the faces and silhouettes of his parents are transposed recurs in Maor’s 2011–2012 exhibit They Are Me, which is a mournful tribute to his parents, filled with memory-objects: his mother’s blouse, his father’s suitcase, family photographs, and yahrzeit candles. In the center of the room a fiberglass cast of the artist’s own naked body (by Israeli sculptress Ofra Zimbalista) is standing in a tub, in a posture echoing that of the earlier depiction of his mother, re-signifying that earlier work as a cipher of memory of the mother now entombed in the son’s body, which is in turn exposed in its vulnerability. The fiberglass sculpture thus harkens back to Maor’s photos from his 1978 series The Mark of Cain, in which nude male figures, mostly of the artist himself, appear in provocative images of bondage, suggestive of corporeal violence. In conjuction with Maor’s later work, these affectively charged compositions can be understood as incarnations of a painful “bondage to memory,” performed by a sexualised male body.

Eroticized portrayals of women used to epitomise the Nazi evil, on the other hand, are critically re-examined in Nancy Spero’s monumental series The Torture of Women (1996). Starting in 1974, the American artist decided to work exclusively with images of women, collecting archetypal female figures from various sources in order to “create a lexicon of the female form in all its guises and incarnations.”28 One of the recurrent images in the series is based on a photograph of a young German woman who was publicly humiliated for the violation of Rassenschande (race defilement) laws. In 1935, the incident received sensationalised coverage in German newspapers and inspired Bertold Brecht to write The Ballad of Marie Sanders, the Jew’s Whore, which was set to music by Hanns Eisler. In the photograph, Marie Sanders is naked except for shoes and stockings that visually stigmatize her as a fallen woman. In Spero’s lithographs, however, she is surrounded by colorful stencils of female goddesses from the artist’s collection, and her body is veiled in warm shades of blue and violet, which seem to be cutting through her bonds. They also restore texture to her hair that had been cut short as part of the spectacle of public humiliation: these gestures effect the protagonist’s transubstantiation from an emblem of shame into a figure of female empowerment. Another eponymic image that Spero includes in her tableau is the scene of the hanging of the Jewish partisan Masha Bruskina, which was based on a photograph taken by a Lithuanian battalion member in October 1941. A legendary symbol of anti-Nazi struggle, Bruskina lightened her hair and concealed her Jewish identity to carry out clandestine assignments, and she remained defiant when she was arrested, publicly humiliated and finally executed. Spero gives Bruskina a stenciled entourage of female goddesses; in one of the iterations of the tableau, she is being lifted up by a powerful Egyptian vulture goddess. Spero’s depictions of female bodies thus illuminate a fetishistic conjunction of violence and sexualization (the photograph of Marie Sanders was a pornographic souvenir found in a pocket of a deceased German soldier, and the hanging of Bruskina has become one of the most widely circulated Holocaust images). By juxtaposing and reworking these twin photographic records of female sexual shame and female heroism, Spero wrests them away from their voyeuristic frameworks, infusing the images with a sense of female sexual and political agency that is both historically situated and endowed with transcendent, mythic power.

Beauty and the Female Body in Holocaust Art: (Re)framing the Frame

As I have shown in the first part of this paper, depictions of female bodies in Holocaust art not only expressed the reality of gendered experiences under extreme conditions, but also served as countervailing symbols of the victims’ extreme suffering and the perpetrators’ “unspeakable evil.” In the face of the collapse of familiar categories and points of reference, these depictions of the feminine, ensconced in socially sanctioned cultural frameworks, thus functioned as a vehicle to express the contents that were both epistemically elusive and affectively difficult to contain. All of these representational strategies, however, were predicated on the erasure of the corporeal, gendered experiences of the victims.

In his seminal essay La représentation interdit [Forbidden Representation] French philosopher Jean Luc Nancy argued that the Shoah brought about the collapse of the entire Western paradigm of representation, as it had been grounded in the idea of truth conveyed through the aesthetic medium. According to Nancy, these insoluble aporias of post-Shoah representation can be productively wrestled with in visual art.29 The examination of Holocaust art through the lens of gender reveals that, while Nancy’s insight is compelling at the ontological and epistemic level, traditional aesthetic concepts and cultural beliefs intractably persevere within the canons of Holocaust representation, regardless of this paradigm shift.

Despite the extreme circumstances to which camp and ghetto inmates were subjected, both wartime and later depictions of atrocities, with few exceptions, did not easily divest themselves of the dictates of traditional aesthetic concepts or familiar cultural tropes. Examples of Holocaust visual art reveal that the aesthetic ideal of beauty cannot be divorced from social constructions of male and female bodies, or from gendered assumptions about agency, testimonial authority and aesthetic sovereignty. However, considering gendered associations of the concept of beauty, the prevalence of violated female bodies in Holocaust iconography also could be interpreted as a displaced traumatic symptom of male artists’ grappling with the aporia of representations of beauty after the Shoah, rather than merely as an expression of misogynist contemporary sensibilities and a repetition of entrenched cultural codes. As I have shown in the second part of this paper, some of the contemporary works inspired by the Holocaust thus also bear Nancy’s insight (which I have inflected with the problematic of gender), that it is in visual art that these challenges can be most fruitfully addressed, thus in turn challenging and transforming established frameworks of meaning and stagnant conceptions of gender.

Bibliography

Alphen, Ernst van. Holocaust Effects in Contemporary Art, Literature and Theory. Stanford: Stanford University Press, 1997.

Amishai-Maisels, Ziva. Depiction and Interpretation: The Influence of the Holocaust on Visual Arts. Oxford: Pergamon Press, 1993.

Apel, Dora. Memory Effects: The Holocaust and the Art of Secondary Witnesses. New Brunswick, New Jersey, and London: Rutgers University Press, 2002.

Blatter, Janet and Sybil Milton. Art of the Holocaust. London: Orbis Publishing, 1982.

Benezra, Neal David, ed. Regarding Beauty: A View of the Late Twentieth Century. Washington D.C: Hatje Cantz Publishers, 1999.

Beylin, Marek. Ferwor: życie Aliny Szapocznikow. Cracow: Wydawnictwo Karakter, 2015.

Costanza, Mary. The Living Witness. Art in the Concentration Camps and Ghettos. New York: Free Press, 1982.

Danieli, Yael. “The Treatment and Prevention of Long-term Effects and Intergenerational Transmission of Victimization: A Lesson from Holocaust Survivors and Their Children.” In Trauma and Its Wake: The Study and Treatment of Post-traumatic Stress Disorder, edited by Charles R. Figley, 295–313. New York: Brunner/Mazel, 1985.

Feinstein, Stephen. “Mediums of Memory: Artistic Responses of the Second Generation.” In Breaking the Crystal: Writing and Memory After Auschwitz, ed. Efraim Sicher, 201–251. Chicago: University of Illinois Press, 1998.

Głowacka, Dorota. Po tamtej stronie: świadectwo, afekt, wyobraźnia. Warsaw: Wydawnictwo IBL PAN, 2016.

Goldenberg, Myrna and Amy Shapiro, eds. Different Horrors, Same Hell: Gender and the Holocaust. Seattle and London: University of Washington Press, 2013.

Hirsch, Marianne. The Generation of Postmemory: Writing and Visual Culture After the Holocaust. New York: Columbia University Press, 2012.

Hedgepeth, Sonja M. and Rochelle G. Saidel, eds. Sexual Violence against Jewish Women During the Holocaust. Boston: Brandeis University Press, 2010.

Hegel, Georg Wilhelm Friedrich, Introductory Lectures on Aesthetics, trans. Bernard Bosanquet. New York: Penguin Books, 1993.

Jedlińska, Eleonora. Sztuka po Holokauście. Lodz: Tygiel Kultury, 2001.

Kant, Immanuel. Critique of Pure Reason, trans. Norman Kemp Smith. New York: St. Martin’s Press, 1965.

Klarsfeld, Serge. David Olère: L’Oeil du Témoin/The Eyes of a Witness. New York: The Beate Klarsfeld Foundation, 1989.

Lecoq, Violette. Témoignages. Les Résistances, photo gallery. http://lesresistances.france3.fr/documentaire-pp/dessins-de-violette-rougier-lecoq.

Lurie, Esther. Jewesses in Slavery. Palestine: Hashomer Hatzair, 1945.

Nancy, Jean-Luc. “Forbidden Representation.” In The Ground of the Image, trans. Jeff Fort, 27–50. New York: Fordham University Press, 2005.

Ofer, Dalia and Lemore J. Weitzman, eds. Women in the Holocaust. New Haven: Yale University Press, 1998.

Parker, Rozsika and Griselda Pollock, Old Mistresses: Women, Art, Ideology. London and New York: I.B. Tauris, 1981.

Pető, Andrea et al. Women and the Holocaust: New Perspectives and Challenges. Warsaw: Central European University Press, 2015.

Pollock, Griselda. Vision and Difference: Femininity, Feminism and the Histories of Art. London and New York: Routledge, 1988.

Presiado, Mor. “A New Perspective on Holocaust Art: Women’s Artistic Expression of the Female Holocaust Experience (1939–49).” Holocaust Studies 22, no. 4 (2016): 417–446.

— “The Expansion and Destruction of the Symbol of the Victimized and Self-Sacrificing Mother in Women’s Holocaust Art.” Nashim: A Journal of Jewish Women’s Studies & Gender Issues, no. 33 (2018): 177–208.

Rosenberg, Pnina. “Women Artists in the Camps/Depictions of Women.” In David Mickenberg et al., The Last Expression. Art And Death. Evanston, Illionois: Mary and Leigh Block Museum of Art, Northwestern University, 2003: 88–94.

— Images and Reflections: Women in the Art of the Holocaust. Lohamei HaGeta’ot: The Ghetto Fighters House, 2002.

Saidel, Rochelle G. and Batya Brutin. Violated! Women in Holocaust and Genocide. New York: Remember the Women Institute, 2018.

Sicher, Efraim. Breaking the Crystal. Chicago: University of Illinois Press, 1998.

Sieradzka, Agnieszka et al. Forbidden Art: Illegal Work by Concentration Camp Prisoners, trans. William Brand. Oświęcim: Auschwitz-Birkenau State Museum, 2012.

Spero, Nancy. From Victimage to Liberation: Works from 1980s and 1990s. New York: Galerie Lelong, 2013.

Stengarst, Tar. “Schock Treatment: Figures of Women in Boris Lurie’s Work.” In No Compromises! The Art of Boris Lurie, ed. Cilly Kugelmann, 216–134. Bielefeld and Berlin: Kerber Publishing Company, 2016.

Waxman, Zöe. Women in the Holocaust: A Feminist History. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2017.

- For discussion of gender-specific experiences during the Holocaust and the exclusion of women’s testimonies in Holocaust rememberance, see, for instance: Dalia Ofer and Lemore J. Weitzman, eds., Women in the Holocaust (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1998); Sonja M. Hedgepeth and Rochelle G. Saidel, eds., Sexual Violence Against Jewish Women During the Holocaust (Boston: Brandeis University Press, 2010); Myrna Goldenberg and Amy Shapiro, eds., Different Horrors, Same Hell: Gender and the Holocaust (Seattle and London: University of Washington Press, 2013); Andrea Pető et al., Women and the Holocaust: New Perspectives and Challenges (Warsaw: Central European University Press, 2015), and Zöe Waxman, Women in the Holocaust: A Feminist History (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2017). See, also: Dorota Głowacka, “Płeć i Zagłada: wyobraźnia relacyjna i zapomniane zaułki pamięci” [Gender and the Holocaust: relational imagination and the cul-de-sacs of memory], in Po tamtej stronie: świadectwo, afekt, wyobraźnia [On the Other Side: Testimony, Affect, Imagination] (Warsaw: Wydawnictwo IBL PAN, 2016), 160–193. ↩︎

- See, for instance: Ernst van Alphen’s Holocaust Effects in Contemporary Art, Literature and Theory (Stanford: Stanford University Press, 1997), and Efraim Sicher’s Breaking the Crystal (Chicago: University of Illinois Press, 1998). ↩︎

- Immanuel Kant, Critique of Pure Reason, trans. Norman Kemp Smith (New York: St. Martin’s Press, 1965). ↩︎

- Notable exceptions are Pnina Rosenberg’s Images and Reflections: Women in the Art of the Holocaust (Lohamei HaGeta’ot: The Ghetto Fighters House, 2002), and several essays on representations of women’s experiences in Holocaust art by Israeli art historian Mor Presiado. See, for instance her analysis of women’s art from the camps and ghettoes in: “A New Perspective on Holocaust Art: Women’s Artistic Expression of the Female Holocaust Experience (1939–49),” Holocaust Studies, no. 4 (2016): 417–446. To date, there is no monograph on the subject of representations of gender in Holocaust art. ↩︎

- Georg Wilhelm Friedrich Hegel, Introductory Lectures on Aesthetics, trans. Bernard Bosanquet (New York: Penguin Books 1993), 60. ↩︎

- Quoted in Neal David Benezra, ed., Regarding Beauty: A View of the Late Twentieth Century (Washington D.C: Hatje Cantz Publishers, 1999), 10. ↩︎

- Olga M. Viso, “Beauty and Its Dilemmas,” in Regarding Beauty, 101. See, also: Rozsika Parker and Griselda Pollock, Old Mistresses: Women, Art, Ideology (London and New York: I.B. Tauris, 1981), XVIII, and Griselda Pollock, Vision and Difference: Femininity, Feminism and the Histories of Art (London and New York: Routledge, 1988). ↩︎

- The exclusion of female artists from the canon of “high” Holocaust art is notable. No female artists, for example, are discussed in Ziva Amishai-Maisels’ seminal study Depiction and Interpretation: The Influence of the Holocaust on Visual Arts (Oxford: Pergamon Press,1993), with the exception of Lea Grundig and references in passing to Alice Lok Kahana, Judy Chicago and Audrey Flack. In her comprehensive volume Sztuka po Holokauście [Art after the Holocaust], Eleonora Jedlińska discusses only one female artist, Magdalena Abakanowicz (Lodz: Tygiel Kultury, 2001). ↩︎

- Mary S. Costanza, The Living Witness. Art in the Concentration Camps and Ghettoes (New York: Free Press, 1982). ↩︎

- Burešová, as quoted in Janet Blatter and Sybil Milton, Art of the Holocaust (London: Orbis Publishing, 1982), 32. For a discussion of sexuality and female beauty in the camps, see: Monika Flaschka, “‘Only Pretty Women Were Raped’: the Effect of Sexual Violence on Gender Identities in the Concentration Camps,” in Sexual Violence, 77–93. ↩︎

- Quoted in Pnina Rosenberg, “Women Artists,” in David Mickenberg et al., The Last Expression. Art And Death (Evanston, Illionois: Mary and Leigh Block Museum of Art, Northwestern University, 2003), 89. ↩︎

- In Esther Lurie, Jewesses in Slavery (Palestine: Hashomer Hatzair, 1945). ↩︎

- For the discussion of the motif of motherhood in Holocaust art, see: Mor Presiado, “The Expansion and Destruction of the Symbol of the Victimized and Self-Sacrificing Mother in Women’s Holocaust Art,” Nashim: A Journal of Jewish Women’s Studies & Gender Issues, no. 33 (2018): 177–208. ↩︎

- See: Violette Lecoq, Témoignages, http://lesresistances.france3.fr/documentaire-pp/dessins-de-violette-rougier-lecoq (accessed: 01.15.2020) ↩︎

- See: Serge Klarsfeld, David Olère: L’Oeil du Témoin/The Eyes of a Witness (New York: The Beate Klarsfeld Foundation, 1989). ↩︎

- Charnel House was showcased at the first exhibition of wartime art, entitled “Art and Resistance,” held February–March 1946, in Paris. ↩︎

- Agnieszka Sieradzka, Forbidden Art: Illegal Work by Concentration Camp Prisoners, trans. William Brand (Oswiecim: Auschwitz-Birkenau State Museum, 2012), 19. ↩︎

- See: https://www.jmberlin.de/fritta/en/phantasmagorien.php (accessed: 01.15.2020). ↩︎

- In Amishai-Maisels, 214. ↩︎

- See: Tar Stengarst, “Schock Treatment: Figures of Women in Boris Lurie’s Work,” in No Compromises! The Art of Boris Lurie (Bielefeld and Berlin: Kerber Publishing Company, 2016), 216–134. ↩︎

- See: Rochelle G. Saidel and Batya Brutin, eds., Violated! Women in the Holocaust and Genocide (New York: Remember the Women Institute, 2018), 21. Catalogue of the pioneering exhibition at Ronald Feldman Gallery in New York (April–May 2018), created by Remember the Women Institute, coordinated by Rochelle G. Saidel and curated by Batya Brutin. ↩︎

- Dora Apel, Memory Effects: The Holocaust and the Art of Secondary Witnesses (New Brunswick and London: Rutgers University Press, 2002), 160. ↩︎

- See: Marek Beylin, Ferwor: życie Aliny Szapocznikow [Fervor: The Life of Alina Szapocznikow] (Cracow: Wydawnictwo Karakter, 2015). ↩︎

- The Scream–Lvov 1941 is part of Button and Tear, Roggel’s 2009 series of Holocaust-themed textile collages. ↩︎

- In Violated!, 68. ↩︎

- Quoted in Stephen Feinstein, “Mediums of Memory: Artistic Responses of the Second Generation,” in Efraim Sicher, ed., Breaking the Crystal: Writing and Memory After Auschwitz (Chicago: University of Illinois Press, 1998), 202. ↩︎

- Yael Danieli, a therapist who worked with children of Holocaust survivors, hypothesized that the fear that their mothers may have been raped was pervasive among especially male members of the second generation. See: Yael Danieli, “The Treatment and Prevention of Long-term Effects and Intergenerational Transmission of Victimization. A Lesson from Holocaust Survivors and Their Children,” in Charles R. Figley, Trauma and It Wake: The Study and Treatment of Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder (New York: Brunner/Mazel, 1985), 295–313. ↩︎

- Nancy Spero (1926–2009), From Victimage to Liberation. Works from the 1980s and 1990s (New York: Galerie Lelong, 2013), 18. For an insightful discussion of Spero’s installation, See: M. Hirsch, The Generation of Postmemory: Writing and Visual Culture After the Holocaust (New York: Galerie Lelong, 2012), 149–152. ↩︎

- Jean-Luc Nancy, “Forbidden Representation,” in The Ground of the Image , trans. Jeff Fort (New York: Fordham University Press, 2005), 27–50. ↩︎

Dorota Głowacka

Dorota Głowacka is Professor of Humanities at the University of King’s College in Halifax, Canada. She is the author of Po tamtej stronie: świadectwo, afekt, wyobraźnia [On the Other Side: Testimony, Affect, Imagination] (2016), Disappearing Traces: Holocaust Testimonials, Ethics, and Aesthetics (2012), co-editor of Imaginary Neighbors: Mediating Polish-Jewish Relations after the Holocaust (2007) and Between Ethics and Aesthetics: Crossing the Boundaries (2002), and editor of Community, a special issue of Culture Machine (2006). Głowacka has published numerous book chapters and journal articles in the area of critical theory and Holocaust studies.