Tytuł

Picturing the Female Gaze Photography as a Form of Cultural Resistance during Romania’s Communist Era

https://www.doi.org/10.48285/ASPWAW.24501611.MCE.2021.7.13

https://miejsce.asp.waw.pl/picturing-the-female-gaze-photography-as-a-form-of-cultural-resistance-during-romanias-communist-era/

Abstrakt

This paper explores photography as a form of cultural resistance during the communist era in Romania (1947–1989) by discussing

the works of the following female photographers and visual artists: Hedy Löffler, Geta Brătescu and Clara Spitzer. They worked in

the context of one of the most severe dictatorships amongst the nations of the former Soviet bloc. Every aspect of cultural, economic, political, and social life was attentively and exclusively controlled by the regime and the secret police, which was ubiquitous in a society under strict surveillance. Although photography was practiced and encouraged as a benign form of expression, it was increasingly deprived of its artistic, social, and documentary power and confined to the realm of amateurism. Stripping photography of its currency enabled the state to maintain control over the camera. Photographers had to be registered members of the regime’s only officially endorsed and financially supported Association of Artist Photographers in Romania (AAFR).

Their photographs were accepted because they seemingly had no social or political implications and sugar-coated ‘socialist reality’, an ideology portraying what life was supposed to look like without documenting the harsh conditions of everyday life during the communist era. Thus, there was a seemingly clear demarcation of photography’s status; artists were discouraged from using photography in their fine art practice, as ‘photographic art’ was only practiced by members of the AAFR. Questioning this separation in relation to gender, this paper frames photography as an ongoing event that is interwoven in webs of power, dialogue, resistance, and agency and involves multiple choices and participants. Drawing on three female artists/photographers, resistance is understood as both opposition and survival, no matter how small these acts of resistance are. Within this framework, female artists/photographers were able to find a space to resist the imposed classifications in subtle ways and take an oblique political stance against the oppressive regime.

DOI

Introduction: ideologically ‘safe’ pictures

Compared to other Eastern European countries of the former Soviet bloc, Romanian photography is relatively rarely discussed in international overviews of photography, with a particular absence of female photographers in this area. Given the different social, cultural, and historical contexts, discussing female photographers in Romania helps develop a more nuanced picture of the history of photography. This paper contributes to this scholarship.

Since the beginning of Romania’s communist rule (1947–1989), art and culture became strictly subordinate to political interests. Emanuela Grama explains that soon after the communist regime assumed power, state officials appropriated and reorganised the existing private and public art collections around the country ‘as a way of revisiting questions of property-holding and value making in early socialism’. 1 With similar intentions, private photography studios were also nationalised. As Adrian-Silvan Ionescu, Ulla Fischer Westhauser and Uwe Schögl describe,

After the communists took power in Romania in the last days of December 1947, all the private photo studios, which had flourished in the inter-bellum period, were nationalized. … Any photographic activity, except portraiture and wedding pictures, was kept under the vigilant eye of the censors. It was only safe to take landscape and cityscape pictures and most amateur photographers focused on scenes of this kind. 2

The idea of what was ‘safe’ to photograph alludes to the official doctrine regarding the production of art and culture, which was aligned to the state’s political ideology. Compared to other socialist countries from the Eastern bloc, the regime in Romania perceived artists and photographers as ‘inherently dangerous’. 3 By implementing the Soviet-backed socialist realism style (later dubbed ‘Ceauşescu realism’) across the arts and cultural sector, artists and photographers were compelled to adopt the idealistic aesthetic. 4

Considered official art, this aesthetic glorified the Romanian past and included homage art depicting the Ceauşescu couple. 5

Paradoxically, socialist realism was not strictly imposed from above but there was an understanding of what was not be photographed and many photographers and visual artists abandoned the artistic styles they had practiced during the interwar period; not producing ‘ideologically safe’ work was risky. 6 Dan Bădescu confirmed this in a recent interview. 7 Working as an official photographer for the Oficiului National de Turism (ONT) 8, for which he photographed landscapes and historic buildings across Romania, Bădescu revealed that he secretly used the films and equipment provided by the ONT to practice his artistic photography.

Experimental in nature (and not necessarily ‘ideologically safe’), he used those pictures to enter the international salons of photographic art as a member of the Association of Artist Photographers in Romania (AAFR). Other artists and photographers, including Hedy Löffler and Clara Spitzer, had a similar approach, which I will discuss below.

Referring to social documentary photographers, Simina Bădică claims that a ‘photographer with sensitivity for the social issues would not only be discouraged and marginalized by the regime but would risk major discomforts’. 9 Anca Pusca similarly asserts that ‘artists gained a special status [and were] constantly monitored, watched and carefully regulated. All art under communism was subject to political manipulation, whether commissioned by the state […] or “autonomous”/“underground” art’. 10 At the same time, photographing everyday life and people at work or in their homes was permitted, as long as these photographs ‘made life in Communist Romania seem nice and happy’. 11 Amateur or unofficial photographers were, then, also not completely free from ideological censorship. As Maria Alina Asavei explains, ‘a neutral […] snapshot of everyday reality was regarded as a politically negligent attitude and even as a potential threat to the regime’s ideology’. 12 Thus, a seemingly innocent snapshot of a man sleeping in public in broad daylight (see fig. 2) was potentially considered a careless viewpoint of everyday life. Picturing socialist life without idealising it was a question of courage. 13

Resisting Ceauşescu’s realism through photography

Despite being one of the most severe totalitarian dictatorships of the former Soviet bloc, there was no large-scale opposition to the regime in Romania and only relatively few courageous individuals dared to voice their criticism against the regime’s increasingly aberrant policies. Several researchers explored culture as a form of resistance, placing the focus on literature, since the country’s dissident culture was text-based. 14 While the visual arts and music have also been investigated as ways to oppose the regime, photography has received relatively little attention as a form of cultural resistance.

This paper adopts Stephen Duncombe’s definition of cultural resistance as ‘culture that is used, consciously or unconsciously, effectively or not, to resist and/or change the dominant political, economic and/or social structure […] cultural resistance can provide a sort of “free space” for developing ideas and practices’. 15 In the context of communist Romania, cultural resistance is understood as opposition and survival, no matter how small these acts of resistance are. By including the process of photographic production and the discursive agency of photographs as a form of cultural resistance, this paper frames photography as an ongoing event that is interwoven in webs of power, dialogue, resistance and agency, and involves multiple choices and participants. Importantly, photography is not inherently a resistance practice but it can be perceived as such when it is used in specific times and spaces. Following Tiffany Fairey and Liz Orton, the idea of dialogic photography ‘centres around the encounters, exchanges and negotiations that happen with, through and around images’. 16 Within this framework, several artists and photographers, both ‘official’ and ‘unofficial’, used their work to oppose the ideological views of the regime. 17

Stripping photography of its documentary, political, and social power

Unlike the strict rules on the ownership and use of the typewriter, owning and using a camera was not placed under the same strict security measures. 18 The regime framed photography in artistic terms, ‘defined by its lack of reference to contemporary phenomena [and] social and political issues’. 19 This seems to suggest that the state recognised photography’s documentary, social and political power and its potential threat to the regime, using several, sometimes subtle, ways to censor the use and circulation of the camera. For example, the lack of quality equipment and training available during the communist era restricted photographers from producing work, which could be considered as a way of regulating the use of photography. Drawing on Roland Barthes’ Camera Lucida, Bădică claims the ‘deliberate confusion’ between (professional) art photography and amateurism ’tamed’ photographic activity and turned it ‘into a politically benign/indifferent activity’. 20 But this view does not account for the complexity within the range of the country’s photographic movement. While Romania did not produce a photographic canon matching that of Western Europe and the USA, referring to photography as a ‘benign/indifferent activity’ diminishes the work of the photographers who were members of the AAFR and strove for international affiliations and collaborations during the communist years.

Romania’s photographic movement

Amateur photographers were first recognised through the establishment of the Association of Amateur Photographers in Bucharest in 1934. Members also issued their own magazine Fotografia (Photography) between 1935–1941, but the association and the magazine were suspended during the war years. In 1956, the association was revived under a new name, the Association of Artist Photographers in Romania (AAFR), and Fotografia continued its circulation from 1968 until 1989. Eugen Negrea emphasises the magazine’s importance by saying that it was ‘the only source of information for the AAF members with respect to the evolution of worldwide photography’. 21

The regime endorsed the photographic movement by way of financially supporting the AAFR. To receive the subsidy was not without problems though, especially during the later years of the regime, when, as Negrea writes, ‘artists had to praise the achievements of the communist regime and were compelled to suspend all connections with Western “decadent art”’. 22 Considering state-sanctioned or official artists were discouraged from using photography during the communist era, it was ironic that you could not be an artist photographer without being a member of the AAFR. Negrea offers a comprehensive account of the history and role of the AAFR but here I want to highlight that two of the founding members were women photographers Hedy Löffler and Clara Spitzer, whom I will discuss from the perspective of gender below.

Gendered photography

Although Romania showed a promising start in terms of the emancipation of women through artistic and creative work, with some professional women photographers working during the early 20th century, relatively few women in Romania were working as photographers before 1989. 23 The records of the AAFR also show few photographs by female photographers. Paradoxically, the communist regime sought to represent women in visual propaganda ‘as men’s equal co-worker’. 24 The intention was to showcase the state’s ‘commitment to gender equality, and women’s occupational status’. 25 These were the official narratives, but gender hierarchies and discrimination persisted in certain sectors, including the arts and culture. 26 Referring to the forgotten ‘Her-stories’ of women’s labour during Romania’s communist period, Asavei and Kocian claim, ‘the representations of women in both media and the arts had been restricted to certain thematic clusters such as the heroine mother, the working women, the caretaker and the sportive woman’. 27 Corina Apostol similarly observes that gender inequality for contemporary cultural producers persists, as ‘most artists in Romania are men, while women have been assigned the role of critics and curators’. 28 However, there were women photographers/visual artists, who sought to create counter-narratives through cultural resistance. The political dimension of their work should not be underestimated.

The three artists and photographers discussed in this paper are Hedy Löffler, Clara Spitzer, and Geta Brătescu. Löffler and Spitzer have received relatively little attention, but as photographers and founding members of the AAFR, their work is worthy of analysis. By contrast, Brătescu had a long career over five decades and is recognised as one of the few female Romanian artists of the 1970s and 1980s (and afterwards). My focus on them will demonstrate that photography enabled them to find a space to contest the ideological classifications in subtle ways and take an oblique political stance against the repressive regime. This, in turn, will help to reconstruct a topic that was taboo before 1989.

Hedy Löffler

As one of the founding members of the AAFR, Hedy Löffler (1911–2007) was a member of the AAFR Steering Committee and Head of the Exhibition Commission, who decided which photographs could enter international salons of photographic art. 29 This was one of the few opportunities for Romanian artist photographers to exhibit their photographs internationally, although that did not necessarily mean artists were allowed to attend the salons in person. While traveling nationally was permitted during the communist era, going abroad was not, bar in exceptional circumstances. 30 Most approved photographs were posted to the salons. Löffler’s role at the AAFR was therefore crucial, as it afforded her greater chances to travel abroad to represent the Association. 31

Described as an ‘outstanding photographer from the communist era’, who was awarded the highest title of the International Federation of Photographic Art, Hon FIAP, Löffler was largely interested in photographing landscapes and local tourist attractions, and produced sixteen photographic albums during the communist era. In order to be published, the albums included several pages of homage pictures of the Ceauşescu couple in colour, depicting them at formal events. 32 For example, Löffler’s album Bucureşti (Bucharest, 1984) starts with a series of twenty photographs portraying either the couple together or Nicolae Ceauşescu alone. The rest of the album illustrates different cityscapes of the capital, interior details and statues. People feature rarely, where they do, it is mainly to promote the workforce or leisure activities (see fig. 1). In that sense, Löffler’s images were safe from the regime’s censorship. However, some of her pictures taken for the AAFR magazine Fotografia or abroad illustrate her artistic ability and interest in depicting everyday life without necessarily idealising it, which reveals her courage.

For example, in 1980 Löffler was granted special permission to visit Paris and took several pictures documenting Parisian everyday life. Whether depicting a man asleep on a bench while seemingly waiting for the metro or a couple kissing in public near the metro’s exit, Löffler’s pictures are striking, and convey a sense of realism and freedom of movement for anyone walking the streets of Paris, Löffler included. Perhaps not immediately clear, but the reason the images are striking in the context of Romanian communism is because they depict the kind of street scenes that were understood not to be photographed during that era. Life in Romania was under strict surveillance and controlled by the regime and the secret police. As a consequence, people kept their lives very private, often not even trusting their own family members or neighbours. Kissing and sleeping were not forbidden, of course, but it was not something to be done in public. As an observer of social reality, Löffler moved through Paris anonymously, like a flâneur. This stands in stark contrast to Romanian society and its lack of freedom of movement during communism. There, Löffler’s landscape photographs and arresting portraits were safe. But for just a moment, and in a rather subtle way, photography enabled Löffler to resist the imposed aesthetics in a different socio-cultural context.

Clara Spitzer

Another founding member of the AAFR, Clara Spitzer (1918–2014) was no stranger to the camera, and owned one since she was fifteen, a few years before her photographic career began. She was hired as a photography apprentice in her hometown, Timişoara, where she gained valuable experience as a studio portrait photographer, a skill that she would pursue throughout her career. Keen to learn more about photography, Spitzer moved to Bucharest, where she met Löffler and became her photography assistant. 33

Spitzer produced a broad portfolio of work throughout her successful photography career. While she worked as a manager at the photography lab of the Ministry of Arts and Information, she also travelled the country far and wide for the Ministry, to photograph the development of cities and the workers on construction sites, demonstrating her strong eye for composition (see figs. 5 and 6). Given the pictures were taken for the Ministry, they were likely used for propaganda purposes, but after the revival of the AAFR in 1956 Spitzer also used her photographs to participate in international photographic salons, such as the salons in Bordeaux and Warsaw in 1957. In her last interview, in 2012, she revealed that she was required to exhibit her photographs to show the development of the country. 34

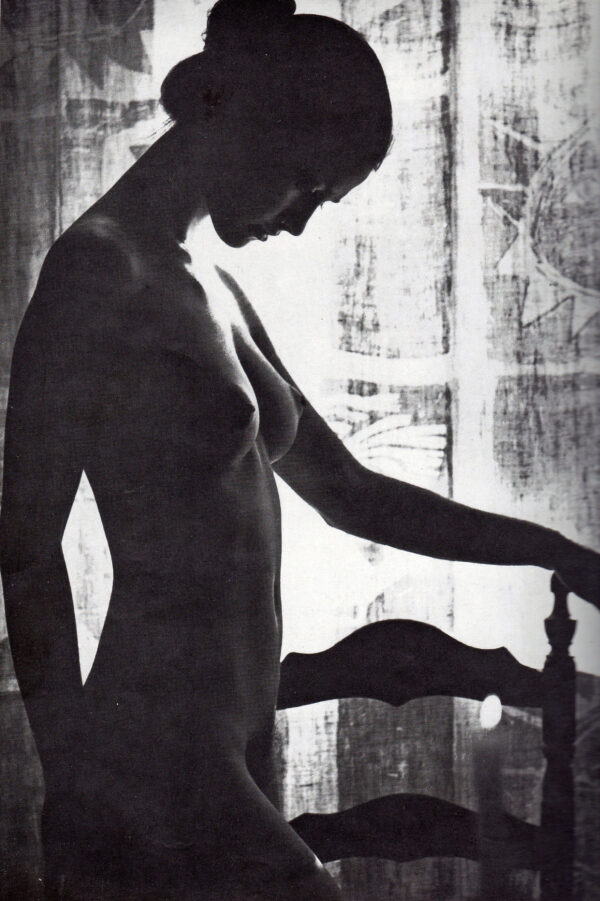

Spitzer’s early experience as a studio photographer made a lasting impression on her, as she mostly preferred taking portraits of actors, especially in black and white. 35 The image of the actor Gheorghe Dinică further depicts her creativity and desire for experimentation. Another example that stands out from the work she did for the Ministry is the profile of a nude that was published in Fotografia (see fig. 8). Despite the AAFR being financially supported by the communist regime, the magazine was not censored, mainly because the director Dr Spiru Constantinescu claimed it was only produced for internal purposes. This was not true, and was a clever move; everything that was produced to be sold externally was censored and required to include homage pictures of Elena and Nicolae Ceauşescu. Fotografia was also sent to international salons in exchange for other international photographic magazines. 36

Geta Brătescu

Geta Brătescu (1926–2018) was one of the few female conceptual visual artists in Romania and worked across different media, including experimental film and photography. However, as a professional artist, she was not a member of the AAFR. Based in Bucharest for most of her long artistic career, that spanned over seven decades, Brătescu initially transformed part of her apartment into her home studio, to experiment with different art forms and themes, describing that ‘the system did not allow much’. 37 She was referring to the communist regime and the classifications it imposed across the arts and culture field. While traditional art forms like painting and sculpture dominated the Romanian art world during the communist era (Brâncuși started his career in Romania), experimental, neo-avant garde art making was heavily censored. Thus, Brătescu’s own, private studio was an intimate and productive space where she could develop as an artist, and employ experimental techniques to explore the relationship between the material world and the abstract form through themes like gender, identity and dematerialisation. Reflecting on her studio, Brătescu asserts,

I bought a studio and acquired this idea of the Studio … as a space of your own, a moral-mystic space. In my Studio I developed myself, step by step, and could be myself. The Studio, that’s more of an idea, an idea about a private space that you’re always carrying along with you, not only a real physical space that you can buy. 38

Understanding the importance of the art studio, which became the centre of her artistic practice, Brătescu later hired a separate studio from her apartment in central Bucharest in the 1970s. Underlining its importance, Brătescu explains,

In the studio you are free and complete, true to yourself, which means that all the information that you carry with you can be translated into a language of communication, because you feel free and liberated from everything that comes from the outside world. 39

Brătescu was well connected with other artists, which helped her develop her artistic career. After she finished her studies at the Academy of Fine Arts in Bucharest, she became the artistic director of the cultural magazine Secolul 20, which afforded her access to resources (including her studio) and opportunities to meet and collaborate with different national and international artists, such as conceptual artist Ion Grigorescu. 40 This also meant she had a wider audience to show her work to in her studio. Interestingly, in her work Towards White (Către alb, 1975), which consists of a sequence of nine black and white photographs, Brătescu transformed the private space of her art studio by gradually covering every object with layers of white paper or fabric until everything was concealed, including her own disappearance within the image. Through this work, Brătescu resisted the imposed version of reality. Moreover, the metamorphosis of the studio could be interpreted as a transformation that dissolved the boundary between the private art space, which provided her with ‘a place of freedom and refuge’, and everyday life during the communist era, which was very restricted. 41 In doing so, the transformative artwork – her photographic sequence – is dialogical within the space. As Brătescu explains, ‘Visual art (with all its fields) is in a direct dialogue with the space within… Any artistic expression is in dialogue with the space’. 42 Describing herself as ‘a rather isolated artist’ during the communist period, Towards White not only enables a dialogue with the space. 43 Drawing again on Fairey and Orton’s idea of dialogic photography that facilitates encounters and human relations, Towards White allowed Brătescu to explore a sense of self and relation to others through photography. This was central in the context of society in communist Romania. As Trond Gilberg argues, Romanian society was ‘not really a society, but rather an agglomeration of individuals who happen[ed] to live on the same territory, subject to the same regime, forced to seek a living in the economic setting in existence’, which was convenient for the regime, as ‘it is much easier to control such a society’. 44 Thus, the idea of photography as dialogue with the studio served as a small act of resistance to the repressive regime, in that Brătescu’s neo-avant garde work was a strategy that enabled her to distinguish herself from the field of cultural politics and reject the socialist realism aesthetic of homage and propaganda art. At the same time, her work was in dialogue with other artists and her collaborators, mainly Ion Grigorescu. However, following the revolution in 1989, Brătescu achieved international acclaim, including at the 2017 Venice Biennale. 45

Photography as a subversive strategy in relation to the female gaze

Where there is power, there is resistance. Considering power as localised and specific, David Green explains,

[T]here cannot be an overall strategy for an oppositional cultural politics of photography; on the contrary it is necessary to develop alternative ways of working with photography, and to develop different photographic forms and devices suitable to the varied contexts in which the photograph is placed and used. 46

As I have tried to illustrate through the works of Hedy Löffler, Clara Spitzer and Geta Brătescu in the context of Romanian communism, photography can be used to develop alternative ways that unsettle hierarchies and power, as well as create new understandings of the world we live in. Although the communist regime asserted control over the camera, all three visual artists/photographers explored photography as a site to resist the imposed classifications in subtle ways and take an oblique political stance against the oppressive regime. Using the female gaze as a prism to help the viewer understand the dynamics at stake, photography enabled the three visual artists/photographers to position their photographic work as a tool for dialogical strategies. They created work from a different perspective. Since there were so few female photographers/visual artists during the communist era (despite the regime’s claim for gender equality across all sectors), the focus on the female gaze helps produce a different and perhaps more nuanced perception through the tool of photography. Or, put differently, the female gaze facilitates the shift towards the untold and unwritten her-story.

Extending Fairey and Orton’s idea of photography as an exchange or encounter of human relations, Ariella Azoulay emphasises the complex nature of photography. It is not only the relationship between the photographer and the sitter/subject in the photograph, but as Azoulay claims, the picture ‘bears the seal of the photographic event’. 47 Proposing the idea of ‘the civil contract of photography’, Azoulay turns from ‘an ethics of seeing … to an ethics of the spectator that begins to sketch out the contours of the spectator’s responsibility of what is visible’ in the photograph. 48 The importance here is that the spectator enters a dialogical space through which they can encourage others to pursue political agency and resistance through photography.

Conclusion

Photographs are a gateway into other stories and information. They bear traces of the photographic event and their intertwining relationship and complicity with discourses of power, gender and culture. Telling those stories is crucial, and in the context of communist Romania, they reveal many unwritten stories of everyday life under the totalitarian regime. Yet, cultural activities are affected and restricted when artistic freedom disappears. Ceauşescu’s control over the arts and culture, which was characterised by imposing an exclusive version of reality and not allowing any artistic expression to flourish if it did not follow the official party ideology, sought to garner artists’ support for his regime, for example through homage painting. 49 Despite the regime’s policies that attempted to diminish professional art, there was room for grassroots resistance through culture. As the three visual artists/photographers discussed in this paper illustrate, they used photography in small ways to resist the official stance on photography and create a space in which they could experiment with their work and maintain their artistic freedom.

Bibliography

Amolini, Daniela, ‘Geta Brătescu: The Studio – A Tireless, Ongoing Space’, Studio International, 1 June 2017 <https://www.studiointernational.com/index.php/geta-bratescu-the-studio-a-tireless-ongoing-space-review> [accessed 11 August 2021]

Apostol, Corina, ‘What Positions Can Women Occupy in Contemporary Art and Culture in Romania’, The Bureau of Melodramatic Research (2011), 1–8 <https://thebureauofmelodramaticresearch.blogspot.com/2012/08/interview-by-corina-l-apostol.html> [accessed 15 April 2021]

Asavei, Maria Alina, Art, Religion and Resistance in (Post-)Communist Romania (London: Palgrave Macmillan, 2020)

Asavei, Maria Alina, ‘Indexical Realism during Socialism’, Photography & Culture, 14, no. 1 (2020), 5–21

Asavei, Maria Alina, Jiří Kocian, ‘Gendered Histories/Memories of Labour in (Post-) Communist Romania and Former Czechoslovakia Illuminated through Artistic Production’, Analize Journal of Gender and Feminist Studies, 8 (2017), 9–37

Azoulay, Ariella, The Civil Contract of Photography (New York: Zone Books, 2008)

Bădică, Simina, ‘Historicizing the Absence: The Missing Photographic Documents of Romanian Late Communism’, Colloquia, 19 (2012), 40–62

Brătescu, Geta, ‘Brass Art’, A Bulletin, 5 (2010 <http://eprints.hud.ac.uk/id/eprint/12785/1/Brass_Art,_A_Bulletin,_issue_5,_Spring_2010 .pdf> [accessed 11 August 2021]

Brătescu, Geta, ‘Interview with Geta Brătescu’ <http://xplaces.code-flow.net/sevova-skin/geta-bratescu-en.html> [accessed 18 April 2021]

Brătescu, Geta, MATRIX 254, exhibition brochure, 2014 <https://bamlive.s3.amazonaws.com/Bratescu-bro.pdf> [accessed 18 April 2021]Duncombe, Stephen, Cultural Resistance Reader (London: Verso, 2002)

Fairey, Tiffany and Liz Orton, ‘Photography as Dialogue’, Photography& Culture, 12 (2019), 299–305

‘Geta Brătescu to Represent Romania at 2017 Venice Biennale’, Artforum, 23 January 2017 <https://www.artforum.com/news/geta-bratescu-to-represent-romania-at-2017-venice-biennale-66157> [accessed 7 September 2021]

Gilberg, Trond, Nationalism and Communism in Romania (San Francisco and Oxford: Westview Press, 1990)

Grama, Emanuela, ‘Arbiters of Value: The Nationalization of Art and the Politics of Expertise in Early Socialist Romania’, East European Politics and Societies and Cultures, 33 (2019), 656–676

Green, David, ‘On Foucault: Disciplinary power and Photography’, in The Camerawork Essays: Context and Meaning in Photography, ed. by Jessica Evans and Barbara Hunt (London: Rivers Oram, 1997), pp. 119–131

Interview with Eugen Negrea, 20 August 2021

Ionescu, Adrian-Silvan, Ulla Fischer Westhauser and Uwe Schögl, ‘Editorial’, PhotoResearcher, 34 (2020), 1–11

Liiceanu, Gabriel, Paltinis Diary (Bucharest: Humanitas, 1991)

Löffler, Hedy, AAFR <http://www.aafro.ro/en/events/din-colecia-aafr-hedy-lffler-hon-fiap/> [accessed 18 April 2021]

Manea, Norman, On Clowns: The Dictator and the Artist (London and Boston: Faber and Faber, 1994)

Massino, Jill, Ambiguous Transitions: Gender, the State, and Everyday Life in Socialist and Postsocialist Romania (Oxford: Berghahn, 2019)

Negrea, Eugen, ‘The Association of Photographer Artists of Romania 1956–2020’, PhotoResearcher, 34 (2020), 88–101

Nochlin, Linda, ‘Why Have There Been No Great Women Artists?’, in Linda Nochlin, Women, Art and Power and Other Essays (New York: Harper & Row Publishers, 1988), pp. 145–176

Pandele, Andrei, Book Insider: Forbidden Photos and Personal Images, 2010 <https://www.romania-insider.com/book-insider-forbidden-photos-and-personal-images-by-andrei-pandele> [accessed 22 August 2021]

Pandele, Andrei, Fotografii interzise si imagini personale, exh. cat. (București: Compania, 2007)

Piotrowski, Piotr, In the Shadow of Yalta: Art and Avant-garde in Eastern Europe 1945–1989 (London: Reaktion Books, 2009)

Preda, Caterina, Art and Politics under Modern Dictatorships (London: Palgrave Macmillan, 2017)

Pusca, Anca, ‘Re-Thinking (Post) Communism after the Aesthetic Turn: Art and Politics in the Romanian Context’, Millennium: Journal of International Studies, 45 (2017), 233–240

Spitzer, Clara, ‘Lecţia de fotografie cu Clara Spitzer’, Asociatia Artistilor Fotografi din Romania, 27 November 2018 <http://www.aafro.ro/en/events/lecia-de-fotografie-cu-clara-spitzer-efiap/> [accessed 26 April 2021]

- Emanuela Grama, ‘Arbiters of Value: The Nationalization of Art and the Politics of Expertise in Early Socialist Romania’, East European Politics and Societies and Cultures, 33 (2019), 656–676 (p. 657). ↩︎

- Adrian-Silvan Ionescu, Ulla Fischer Westhauser and Uwe Schögl, ‘Editorial’, PhotoResearcher, 34 (2020), 1–11 (p. 7). ↩︎

- Anca Pusca, ‘Re-Thinking (Post) Communism after the Aesthetic Turn: Art and Politics in the Romanian Context’, Millennium: Journal of International Studies, 45 (2017), 233–240 (p. 236). Moreover, Norman Manea shares his own experience about art and culture under Ceauşescu’s regime in On Clowns: The Dictator and the Artist (London and Boston: Faber and Faber, 1994). ↩︎

- Maria Alina Asavei, Art, Religion and Resistance in (Post-)Communist Romania (London: Palgrave Macmillan, 2020), p. 38. ↩︎

- Caterina Preda offers a detailed account of Ceauşescu’s official principles in relation to art and culture, which were manifested with the 1971 ‘July Theses’ and reiterated with the ‘Mangalia Theses’ in 1983. See Caterina Preda, Art and Politics under Modern Dictatorships (London: Palgrave Macmillan, 2017), pp. 141–210. ↩︎

- Maria Alina Asavei, Art, Religion and Resistance, p. 49 ↩︎

- Dan Bădescu was an apprentice of Clara Spitzer and the youngest photographer to become a member of the Association of Artist Photographers in Romania in 1957. The interview was conducted by the author on 19 August 2021. ↩︎

- The ONT was the National Tourist Office during the communist years. ↩︎

- Simina Bădică, ‘Historicizing the Absence: The Missing Photographic Documents of Romanian Late Communism’, Colloquia, 19 (2012), 40–62 (p. 56). ↩︎

- Anca Pusca, ‘Re-Thinking (Post) Communism’, p. 236. ↩︎

- Ibidem. ↩︎

- Maria Alina Asavei, ‘Indexical Realism during Socialism’, Photography & Culture, 14, no. 1 (2020), 5–21 (p. 5). ↩︎

- The architect Andrei Pandele secretly photographed Bucharest during the demolition of the city’s old part, which Ceauşescu ordered in order to build Casa Poporului (the People’s House, now the Palace of the Parliament). Pandele waited for 18 years before he exhibited the photographs for the first time in Bucharest in 2007–2008 <https://www.romania-insider.com/book-insider-forbidden-photos-and-personal-images -by-andrei-pandele> [accessed 22 August 2021]. See also AndreiPandele, Fotografii interzise si imagini personale, exh. cat. (București: Compania, 2007). ↩︎

- See, for example, Caterina Preda, Art and Politics, p. 259; Gabriel Liiceanu, Paltinis Diary (Bucharest: Humanitas, 1991), pp. 6–7, and Norman Manea, On Clowns. ↩︎

- Stephen Duncombe, Cultural Resistance Reader (London: Verso, 2002), p. 5. ↩︎

- Tiffany Fairey and Liz Orton, ‘Photography as Dialogue’, Photography & Culture, 12 (2019), 299–305 (p. 299). ↩︎

- Piotr Piotrowski observes that some countries in the former Soviet bloc had two cultural scenes (an ‘official’ and ‘unofficial’ one) functioning in parallel, which was also common in Romania. See Piotr Piotrowski, In the Shadow of Yalta: Art and Avant-garde in Eastern Europe 1945–1989 (London: Reaktion Books, 2009). ↩︎

- Simina Bădică, ‘Historicizing the Absence’, pp. 46–47. ↩︎

- Ibidem, p. 42. ↩︎

- Ibidem, p. 40. ↩︎

- Eugen Negrea, ‘The Association of Photographer Artists of Romania 1956–2020’, PhotoResearcher, 34 (2020), 88–101 (p. 96). ↩︎

- Ibidem, pp. 97–98. ↩︎

- Jill Massino’s book Ambiguous Transitions: Gender, the State, and Everyday Life in Socialist and Postsocialist Romania (Oxford: Berghahn, 2019) offers insights into the working conditions for women during the communist era. ↩︎

- Maria Alina Asavei and Jiří Kocian, ‘Gendered Histories/Memories of Labour in (Post-) Communist Romania and Former Czechoslovakia Illuminated through Artistic Production’, Analize Journal of Gender and Feminist Studies, 8 (2017), 9–37 (p. 15). ↩︎

- Jill Massino, Ambiguous Transitions, p. 5 ↩︎

- This was not only the case in Romania, which Linda Nochlin described so eloquently in her essay ‘Why Have There Been No Great Women Artists?’ (1971), in Linda Nochlin, Women, Art and Power and Other Essays (New York: Harper & Row, Publishers, 1988), pp. 145–176. ↩︎

- Maria Alina Asavei and Jiří Kocian, ‘Gendered Histories’, pp. 14–15. ↩︎

- Corina Apostol, ‘What Positions Can Women Occupy in Contemporary Art and Culture in Romania’, The Bureau of Melodramatic Research (2011), 1–8 (p. 2). <https://thebureauofmelodramaticresearch.blogspot.com/2012/08/interview-by-corina-l-apostol.html> [accessed 15 April 2021]. ↩︎

- Hedy Löffler, AAFR <http://www.aafro.ro/en/events/din-colecia-aafr-hedy-lffler-hon-fiap/> [accessed 18 April 2021]. ↩︎

- Moreover, families were not allowed to travel abroad together, and it was common that children stayed with family members as a guarantee in Romania, while their parents were granted a short visa to leave the country. ↩︎

- This information was provided by Eugen Negrea in an interview on 20 August 2021. Negrea is the current Director of the AAFR. ↩︎

- Löffler was one of the first photographers in Romania to use colour film when it became available. ↩︎

- Clara Spitzer, ‘Lecţia de fotografie cu Clara Spitzer’, Asociatia Artistilor Fotografi din Romania, 27 November 2018 <http://www.aafro.ro/en/events/lecia-de-fotografie-cu-clara-spitzer-efiap/> [accessed 26 April 2021]. ↩︎

- Ibidem. ↩︎

- Spitzer also had access to colour films when they became available in Romania. ↩︎

- Interview with Eugen Negrea, 20 August 2021. ↩︎

- Geta Brătescu, ‘Interview with Geta Brătescu’ <http://xplaces.code-flow.net/sevova-skin/geta-bratescu-en.html> [accessed 18 April 2021]. ↩︎

- Ibidem. ↩︎

- Geta Brătescu, ‘Brass Art’, A Bulletin, 5 (2010). <http://eprints.hud.ac.uk/id/eprint/12785/1/Brass_Art,_A_Bulletin,_issue_5,_Spring_2010.pdf>[accessed 11 August 2021]. ↩︎

- Daniela Amolini, ‘Geta Brătescu: The Studio – A Tireless, Ongoing Space’, Studio International, 1 June 2017 <https://www.studiointernational.com/index.php/geta-bratescu-the-studio-a-tireless-ongoing-space-review> [accessed 11 August 2021]. ↩︎

- Geta Brătescu, MATRIX 254, exhibition brochure, 2014 <https://bamlive.s3.amazonaws.com/Bratescu-bro.pdf> [accessed 18 April 2021]. ↩︎

- Geta Brătescu, ‘Brass Art’. ↩︎

- Geta Brătescu, ‘Interview with Geta Brătescu’ ↩︎

- Trond Gilberg, Nationalism and Communism in Romania (San Francisco and Oxford: Westview Press, 1990), p. 145, original italics. ↩︎

- Geta Brătescu to Represent Romania at 2017 Venice Biennale’, Artforum, 23 January 2017 <https://www.artforum.com/news/geta-bratescu-to

-represent-romania-at-2017-venice-biennale-66157> [accessed 7 September 2021]. ↩︎ - David Green, ‘On Foucault: Disciplinary power and Photography’, in The Camerawork Essays: Context and Meaning in Photography, ed. by Jessica Evans and Barbara Hunt (London: Rivers Oram, 1997), pp. 119–131 (p. 129). ↩︎

- Ariella Azoulay, The Civil Contract of Photography (New York: Zone Books, 2008), p. 14 ↩︎

- Ibidem, p. 130. ↩︎

- A famous homage painting was created by Romanian painter Dan Hatmanu in 1983, which he titled Aniversare/Anniversary. Rather hidden in a corner, it is displayed at the National Museum of Contemporary Art (MNAC) in Bucharest. ↩︎

Uschi Klein

Dr Uschi Klein is an early career researcher and lecturer at the University of Brighton, UK. Her current research focuses on photography as a form of cultural resistance in communist Romania (1947–1989), as well as on decolonising the Western photography canon to broaden knowledge by including marginalised and under-represented perspectives. Her recent publications include a chapter in the volume The Camera as Actor (Routledge 2020) and articles in academic journals, including Visual Studies and Visual Communication.