Title

The Brick Wall in Andrzej Wróblewski’s ”Execution against a Wall” and Jean-Paul Sartre’s ”Le Mur” An Intertextual Relation

https://www.doi.org/10.48285/8kaepzco3p

https://miejsce.asp.waw.pl/en/ceglany-mur-w-rozstrzelaniu-na-scianie-andrzeja-wroblewskiego-i-le-mur-jeana-paula-sartrea-relacja-intertekstualna/

Abstract

In 1949, Andrzej Wróblewski (1927–1957) created eight paintings entitled ”Executions”. They were an attempt to develop a new language for art, which was facing a crisis of representation after the horrors of the war. This article takes on the task of an analysis and interpretation of Wróblewski’s ”Execution against a Wall”, a painting that has largely been overlooked and disregarded as conventional.

In ”Execution against a Wall”, the wall limits the field of vision while forcing the viewer to engage in the performance, creating an arena or stage. I discuss the many visual sources that also depict executions set against the background of a wall. Iconic depictions by Goya, Manet, and Picasso were fundamental for works from the 1930s, 1940s, and 1950s. I also discuss how brick walls take on various functions in different depictions, constructing the composition and the semantic field of the painting whilst underlining the specificity of the painting as a medium and the two-dimensionality of the canvas.

My intertextual interpretation of ”Execution against a Wall” is based on parallels between Jean-Paul Sartre’s short story ”Le Mur” and Wróblewski’s painting. In the case of Wróblewski’s work we are confronted with a representation of two people who, in the face of looming death, start to resemble each other. Any individual qualities disappear and differences are abolished, yet death does not unite them.

DOI

During a period of several months in 1949, Andrzej Wróblewski created eight oil paintings titled Executions, devoted to images of war and human confrontation with the evils of history. Those works proposed a new direction for Polish art, which – according to the artist’s intention – was meant to respond to the needs of the new society and to shape it.1 In this text2 I would like to put forward a new interpretation of Execution against a Wall (Execution IV),3 in which I emphasize the importance of the positioning of the portrayed figures against a brick wall and the viewer’s direct confrontation with them. This perspective challenges the widespread interpretation of the two represented figures as one person at two different moments of existence: alive, seconds before the execution, and dead afterwards. At first glance, their physical similarity compels us to consider the two men as identical. Furthermore, the motif of dividing the moment of death into a sequence of stages, familiar from other Wróblewski paintings (such as Surrealist Execution) – the attempt to capture the specific point at which a living person becomes dead – lends further legitimacy to such an understanding of Execution against a Wall. Doubts arise, however, when we consider the brick wall against which Wróblewski situated the figures, as it implies the unity of space and shatters the temporal consistency of the painting.

In this text, I propose a double-track analysis of Wróblewski’s painting through the prism of the motif of the wall. My interpretation of the piece is based on intertextual methodology, which studies the relations between the reading of a text and previously known cultural texts. An important point of reference concerning this methodology is found in Stanisław Czekalski’s publication devoted to the topic.4 Evoking Julia Kristeva, Roland Barthes, and Jacques Derrida, Czekalski proposes implementation of the intertextual research apparatus in the field of art history. According to such an understanding of the relations between the subject and language, images are said to process and borrow visual conventions on a similar basis to texts. The process of developing relations is connected with the practice of reading, while the presence of borrowings is not an objective fact, but depends on recognition by the viewer. I therefore begin with a horizontal cross-section of examples of artworks themed around executions and brick walls, analyzing various functions played by the walls therein. I discuss paintings by Goya, Manet, and Picasso as works of fundamental importance for later representations in the 1930s, 1940s, and 1950s. I thus explain the meanings attributed to the wall by artists of the same period as Wróblewski. I later draw parallels between Wróblewski’s piece and Jean-Paul Sartre’s Le Mur, which features wall and execution motifs, significant for a new reading of the painting in question. Although it remains unknown whether Wróblewski knew Sartre’s text, I believe that it complements his Execution against a Wall in an interesting way, a painting imbued with a surreal sense of threat and tragedy. Based on an existential trope, the intertextual reading of Wróblewski’s work throws into question the identities of the two men depicted in the painting.

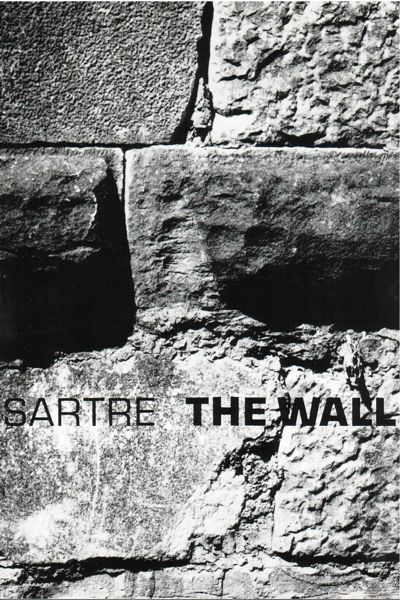

Jean-Paul Sartre, ”The Wall”, 1969, New Directions Publishing, New York, © 1975, photo by Roloff Beny, courtesy of New Directions

Execution against a Wall

Execution against a Wall stands out among other paintings in Wróblewski’s series due to the prominent presence of a brick wall, which seems to be vanishing in the other Executions. A fragment of a wall can be seen in The Poznań Execution and The Family Execution (Execution III), where the azure-blue male figure resembles the figures from Execution against a Wall. The scenographic character of the wall in The Family Execution is further underscored by the fact that it occupies merely half of the painting, marking a division between temporal zones: waiting for the firing squad to shoot (on the left); the moment of death (in the center, with the arrangement of the man’s hands, akin to Jesus on the cross, maintaining risky proximity to the Christian motif); and the past which led to that situation (on the right), where the man is depicted in a guerrilla fighter’s outfit. In other Executions, the wall disappears completely: in Surreal Execution, for example, the space is constructed from entirely different means. The wall appears in other Wróblewski paintings from the same period: in the watercolor 3 X YES5 and in Train Station in the Recovered Territories from 1949.

Execution against a Wall depicts two men situated symmetrically next to one another, side by side. The axial composition further emphasizes the dichotomy that lends the painting its powerful appeal. Wróblewski made use of clear visual indices such as repetition and conglomeration6 in order to express the inevitability of the fate of the subjects and ultimate dehumanization. The vertically oriented painting is of considerable size, measuring 120 x 90 cm. Painted with realistic strokes and broad outlines, the men stand against an unplastered wall of red brick, shown slightly from below. The form is simplified and synthetic, painted with flat patches of color. Wróblewski painted figures of the executed using a cool shade of blue, as if the colors of their bodies had evaporated together with their lives – akin to a body cooling down after death; the azure blue also evokes the sky and infinity. The light appears supernatural, as is often the case in Wróblewski’s works. In Execution against a Wall, both men cast a shadow. The space in the painting is very shallow, almost entirely filled by the figures, their feet touching the edge; there is no room for escape or to move backwards. The men have their backs to the wall, both literally and metaphorically. Both are holding their hands behind their backs – probably tied by the perpetrators. Arms and hands usually function as an important means of expression and conveying meaning; in this case, they underscore the absolute powerlessness of the figures, their fates being completely out of their hands.

The gaze of the man on the left shows utter resignation – his dead eyes appear absent and look fixedly into space, without meeting the eyes of the viewer. His gaze, from underneath the eyelids, provokes anxiety, introducing a sense of tension and anticipation. I can imagine this man, with a red tie, suddenly making a slight move so that his eyes come towards me, encountering my gaze. His potential field of vision therefore fuels the viewer’s uncertainty as to his or her existence in the reality of the painting. If we assume that the viewer is present, what role does he or she appear in – participant or witness? I suppose that was one of Wróblewski’s strategies, used in order to establish a new relation between the artwork and the viewer, and to profoundly engage the latter.

The man on the left stands straight and tense. A similar figure appears in another painting, The Poznań Execution, although his facial features are more strongly defined and older, and the color of his suit differs. Providing dramatic contrast, the figure on the right of Execution against a Wall is twisted in a spasmodic contortion and represented in cool tones of azure blue, usually employed by Wróblewski to denote death and underline the inner dynamics of a painting. As if from the force of a bullet’s blow, the man’s hands remain behind his back, but his feet are already turned right, while the head leans dynamically to the left. His eyes are shut, the lips are pressed together. He might be uttering a sound, breathing his last gasp, or moaning, as the mouth is not yet inert and open. His disheveled hair and the open flaps of his jacket, as if from a gust of wind, produce the impression of movement. The figure is falling, just about to collapse to the ground and perhaps break into pieces.

At first glance, we instinctively recognize the two figures as the same person, yet their clothes differ: the man on the left is wearing a suit, shirt, and red tie, with shoes on his feet. The color of the tie might be indicative of his political beliefs, a manifesto of belonging to the ranks of the builders of the new order. The attire is similar to the suits in which Wróblewski posed for self-portraits.7 In turn, the figure on the right is barefoot and without a shirt and tie. His heavy, sculpturally rendered feet are rising from the ground. The trousers and jacket appear to be the same – even the folds and creases of the fabrics match. Buttons on men’s jackets are usually on the right-hand side, as is the case in the paining.8 This is significant, as it reveals that the painting’s surface is not a mirror – if it were, the buttons would appear on the left-hand side of the jackets. It is therefore not a reflection of the painter’s or viewer’s reality, but a separate reality of representation in its own right.

Andrzej Wróblewski, ”Self-Portrait”, 1949, oil on canvas, 90 × 60 cm, © Andrzej Wróblewski Foundation, courtesy of the Andrzej Wróblewskiego Foundation / www.andrzejwroblewski.pl

As in almost all the other Executions,9 the painting does not depict the perpetrators. The reason behind the death sentence also remains unknown. Perhaps the artist thus seeks to suggest that the crime for which the man was convicted was not a true or truly significant crime. Execution III features a figure interpreted sometimes as a guerrilla fighter, which would clearly explain the reason behind his execution. In Execution against a Wall, only the tie worn by the man on the left seems to vaguely suggest that he is being executed for his political convictions.

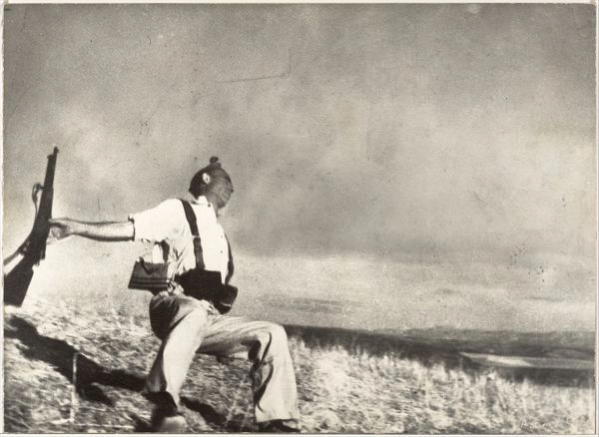

Wróblewski wrote in the catalog of the 1st Exhibition of Modern Art that his proposed artistic formula was “photographic.”10 This can be seen particularly clearly in the figure of the executed man (or the one currently being killed), portrayed like a snapshot, almost as in photojournalism. The source of this representation might have been Robert Capa’s The Falling Soldier from 1936, which depicts the phenomenon of death through the medium of photography. The image captures the decisive moment of no return, although the spark of life may still be smoldering. That Wróblewski mentioned the “photographic” ambition of painting comes as no surprise, since photography was the medium that most fully articulated the specificity of the era. Immediately after the war, photographic images flooded the press, often depicting acts of violence.11 Artistic, journalistic, and documentary photography also functioned as a tool of propaganda. This inevitably left its mark on art. Some researchers of Wróblewski’s work have pointed out the artist’s potential inspiration by the propagandistic photographic documentation of the execution of civilians in Bydgoszcz in 1939.12 The composition of one of those images seems to have been repeated in Surreal Execution – a group of men are standing at an angle against the background of a building with a bossage facade. Other photographs feature a wall, although not a brick one.

Paintings are usually read from left to right, a convention with which Wróblewski played games, for example in Train Station in the Recovered Territories, Waiting Room – the Rich and the Poor, and Waiting Room I – The Queuing Continues, where visual indexes, such as a station master’s pennant, an arrow, or a poster on the wall send the eyes back again to the left side, as if in a loop, completing the circular movement of the gaze. In Waiting Room I, the effect is a metaphysical sense of waiting for nothing. In Execution against a Wall, the arrangement of the bodies suggests a certain circularity, as the curve of the blue figure’s body directs the gaze back to the living man on the left.

Andrzej Wróblewski, ”Train Station (Waiting Room – the Rich and the Poor)”, 1949, oil on canvas, 134.5 × 199 cm, private collection, © Andrzej Wróblewski Foundation, courtesy of the Andrzej Wróblewski Foundation / www.andrzejwroblewski.pl

The visualization of time in the Executions was pointed out by Piotr Piotrowski,13 who evoked the motif of “life flashing before you” at the moment of death and the division of dying into its logical stages: the beginning, the culmination, the end. Piotrowski considers the paintings as the artist’s attempt to depict the state of consciousness of the victims. In Wróblewski’s work, war debases people.14 With terror written on their faces, the figures populating his paintings wear masks of animal fear. The horror objectifies the victims, stripping them of humanity. This dramatism becomes even more acute when the figures are dismembered and fragmented.

Bricks, wall, and execution – relations between images

What is the role of the wall and the bricks in the painting? What is the status-as-paintings of those that depict a wall? Let us imagine Execution IV hanging on a wall. When this happens, the execution of the painting itself also takes place. Since the perpetrator-executioner is absent, the viewer’s gaze carries out the execution of both the figure in the painting and – going a step further – the painting itself. What is more, the depiction of a wall that significantly reduces the depth of representation gives the painter the possibility to prominently highlight and distinguish the action in the foreground. The image can be flattened and decluttered, providing enough air for the represented situation – for the closing of an action between the viewer and the rest of the space in the painting, which is fenced off, compressed, and eliminated. The viewer is faced with an execution scene simultaneously as an observer and perhaps also as the executioner, whose tool is the gaze.15 Wróblewski’s painting places the viewer as the culprit. And yet, just like the two men, he or she is pressed back against the wall – a witness, a perpetrator, and also a potential victim. This compels us to ask about the status of such representation. From what position are we supposed to view the painting? Who are we as viewers of the depicted situation – are we looking at a painting or witnessing an execution?

Representations of executions against walls gained a greater presence in European painting in the 19th century for the simple reason that firearms became more widespread. The motif was most famously rendered in Francisco Goya’s The Third of May 1808 from 1814, which set an iconographic model for later representations. Artists sought to evoke strong emotions – fear and anger – eliciting a specific political reaction from the viewer. Although Goya’s piece does not feature a wall, there is a clear dramatic distinction between those executed and those shooting. This trope has already been explored in interpretations by such scholars as Jan Białostocki,16 Andrzej Kostołowski,17 and Marta Dziewańska,18 who highlighted the significant absence of perpetrators from Wróblewski’s representations.

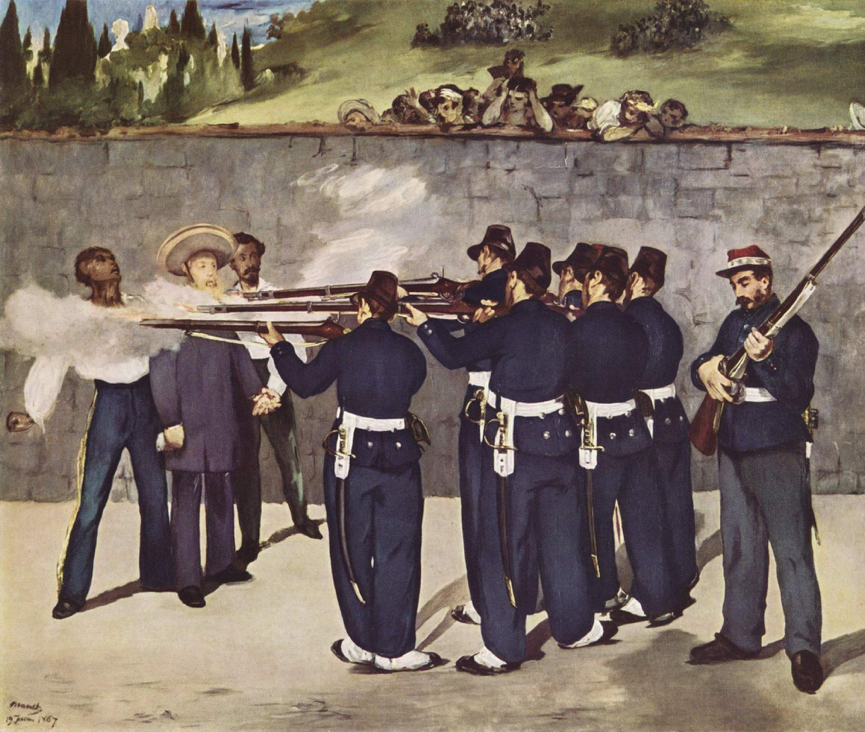

Another painting in the visual genealogy of Execution against a Wall is The Execution of Emperor Maximilian by Édouard Manet in its version from 1869 (currently in the collection of the Städtische Kunsthalle Mannheim). Manet based his work on the images from press coverage of the event. He openly alluded to the composition of Goya’s The Third of May while also drawing from his bullfighting paintings in order to make the place of execution resemble an arena, a site of ritual animal killing.

The curator John Elderfield notes that Manet removed a key element from the last version of his work that can be seen in the earlier paintings: a sabre raised by one of the soldiers as a sign to open fire.19 A material object is therefore missing which previously served directly as the trigger of the killing. What does this decision mean? What kind of narrative of execution is developed? As in Wróblewski’s work, this is a vision of an execution without a cause, happening before the eyes of a crowd staring aghast from behind a wall with no understanding of who really bears responsibility.

Elderfield highlights the way Manet represents relations not only in spatial, but also temporal terms, depicting the entire scene as if in slow motion: we see the smoke dissipating slowly above the general’s head, unveiling the brick wall. The painting seems to capture the very moment of shooting – a fraction of a second, with the bullets almost visible in the air. A similar interpretation – as the very moment of death, albeit divided between a number of figures – was put forward by Piotr Piotrowski with regard to Wróblewski’s The Surreal Execution.20 Like Manet, Wróblewski compels the viewer to play the scene anew with every gaze. In the Manet painting, one of the bullets has already reached General Tomás Mejía – his head and arms are thrown back, his eyes are closed, and his mouth is open, giving out a last cry. His chest is shrouded in a gray cloud, protecting the massacred body from the viewer’s gaze. The dead figure in Execution against a Wall appears to repeat the arrangement of the general’s body on the left of Manet’s painting, as he bends to the side with his head flung back. Emperor Maximilian is still alive, standing straight and pale, a sombrero encircling his head like a saint’s halo. He seems not to belong to the representation, as if he were already part of a different space. He likely clutches the hand of the other general, who stares fixedly at the firing squad in front of them. Wróblewski’s painting also features such a dramatically human gesture: two figures in The Surreal Execution are holding one another’s hands.

A shadow can be seen in the corner of the Manet painting, which – as Elderfield proposes – is being cast by the viewer. A shadow that transcends the borders of the painting is also present in Wróblewski’s The Surreal Execution; according to Piotrowski, it belongs to a child who is not portrayed directly in the painting, but has accompanied the man.21 In Manet’s piece the sergeant figure, preparing the musket to shoot, stands above the shadow. Should the firing squad fail to promptly put the convicts to death, the sergeant may open fire again to complete the task. It is known that the emperor’s execution took a dramatic course, and further shots were necessary, which increasingly strained the soldiers’ nerves. Therefore, while we are looking at the sergeant, Manet wants us to imagine what is going to happen in the very next moment, when he drops the firearm in fury while hastily reaching for it and two soldiers miss from close distance. The representation is evocative of the horror of the officially sanctioned cruelty of political power.

What role does the wall play in Manet’s piece? It is obviously a background in the sense that it serves to lend further visibility to what is happening in front of it. But Manet’s wall is also an arena – it closes off the space of the painting, reinforcing the sense that the victims are hemmed in. The crowd of onlookers is separated; only the viewer is there, with the victims facing the firing squad and the wall behind them. Manet’s paintings already belong to modernity, and the extensively painted wall also becomes a manifesto of painting’s power, which manifests itself in the nearly abstract gray surface.

The paintings by Goya and Manet are recognized as seminal representations of execution by firing squad. Another interesting piece in this respect is Pablo Picasso’s Guernica from 1937.22 Similarly to the two previously discussed works, it was created to express opposition to a political regime. Picasso conveyed the horror of the bombarded city through fragmented human and animal bodies, and while there is no brick wall in Guernica (only fragments of roofing tiles), it brings to mind such Wróblewski paintings as The Surreal Shooting and Painting about the Horrors of War (Fish without Heads). Guernica is one of the fundamental artworks for the consciousness of the mid-20th century, and some of its elements may either have inspired Wróblewski directly or informed his decisions. As an erudite graduate in art history, the artist surely knew Picasso’s masterpiece from basic readers on the latest in the arts.23

Pablo Picasso, ”Guernica”, 1937, oil on canvas, 349.3 × 776.6 cm, Museo Nacional Centro de Arte Reína Sofia, Madrid

As in Guernica, the motif of animals cut into pieces also appears in Wróblewski’s depiction of fragments of fish in Painting about the Horrors of War from 1948, shown for the first time at the 1st Exhibition of Modern Art. The interplay between the title and content is indicative of the Surrealist character of the image – Surrealism was a major discourse in Polish painting of the 1940s.24 Akin to Sartre, Picasso belonged to the French Communist Party and participated in the World Peace Council in 1948 in Wrocław. He was viewed favorably by the Polish communist authorities, albeit rather as a party member seeking historical justice than as the artist behind such works as Guernica.

Another potential visual source was pointed out by Waldemar Baraniewski, who traced the connections between Wróblewski’s paintings and previous representations of war in Polish visual culture.25 Baraniewski demonstrated traces of the unquestionable influence of Artur Grottger’s immensely popular series on Wróblewski’s Executions. The scholar recognizes this kinship as a conscious game and dialogue, although Wróblewski could obviously not openly admit to such tapping of sources.26 Yet, this can be clearly seen in a comparison between Grottger’s The First Sacrifice from the series Warsaw I and Execution against a Wall, and to an even greater degree in one of the sketches for the former. The similarities comprise the diagonal composition that lends the image a dynamic character, along with the drawing of the clothing, the monumental appeal, the almost photojournalistic depiction of the scene, and the analogous point of view from below. The victim figure is shown between two walls: the one against which the man slumps and the one from behind which the deadly shot has just been fired. The gestures and the dynamic of the body struck by a bullet in Wróblewski’s painting also appear to owe a lot to Grottger’s influence.

The wall in the consciousness of Polish artists

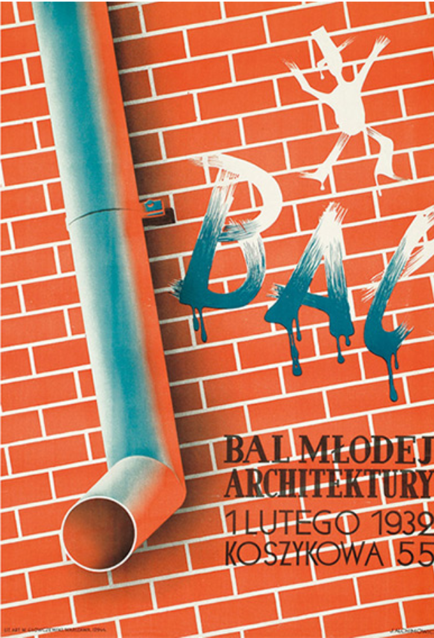

To gain a better understanding of Wróblewski’s painting, let us think about what the wall meant for artists in the 1930s, 1940s, and 1950s, and examine examples of this motif in Polish artistic work. A wall also appears in the Young Architecture Ball poster designed by Maciej Nowicki and Stanisława Sandecka in 1939.27 Set against the brickwork is a modern gutter and the word “ball” painted directly on the wall. In the poster, the wall is a structural element of the building – Nowicki and Sandecka were architects. Walls functioned as an important means for information to circulate in the public sphere, crammed with posters of theatre spectacles and political candidates, which is why the inscription “ball” appears directly on the brick surface.

The wall is also a site of straightforward political struggle. During the Nazi occupation, a Home Army soldier painted an anchor, the symbol of Fighting Poland, on the Aviator Monument in Warsaw’s Union of Lublin Square during a “minor sabotage” operation. What is the status of the wall and public space here? What is the sign on the wall and how does the wall become a carrier of public messages? The plinth of the monument was turned into a site of resistance to the regime, a disruptive operation similar to such slogans written on walls as “Only swine watch the German line,” in reference to attending cinemas. The walls became a similar battleground in 1946 during the people’s referendum, when the partisans of the new communist authorities began to paint them with the slogan “3 X YES.” Wróblewski represented such inscriptions in a number of his paintings and graphic works, which testifies to his awareness of the struggle waged on the walls. In the painting Waiting Room – the Rich and the Poor from 1949, in line with Socialist Realist principles of representing different classes, a fat capitalist and his wife sit on a bench amid a bunch of unbridled children, while a poor woman rests on the floor next to them, in the lap of her vigilant husband. The group wait in a station waiting hall for a westbound train. A red flag waves behind the window, a symbol of the new political order. The “3 X YES” inscription can be seen behind the back of the two men, partly veiled by the plutocrat’s elbow and the proletarian’s head.

An interesting reference to the wall can be found in Felicjan Szczęsny Kowarski’s painting Proletarians, presented at the Recovered Territories Exhibition in Wrocław in 1948. The work portrays the first Marxists locked in a prison cell, where they sit against the background of a brick wall, which therefore becomes a visual representation of the oppression of capitalist power. There is one more painting by Kowarski that features a wall: Electra from the Human series, which depicts an antique figure against a background of columns and ruins. The painter addresses the play by Jean Anouilh, perceived as a tribute to the Warsaw Uprising, and in this context the painting may be interpreted as a political statement. References to antiquity were actually quite popular in representations of war ruins. The curators of the show Just after the War, Joanna Kordjak and Agnieszka Szewczyk, see their presence as a gesture meant to add a sublime quality to war losses and the reconstruction effort.28 In a similar way, a political declaration can be found in Izaak Celnikier’s painting Ghetto from 1949.29 Evoking the motifs of the Pietà and the Entombment, it depicts a scene from the wartime tragedy of a Jewish ghetto, which unfolds against the backdrop of a partly plastered wall.

The call in the title of Aleksander Kobzdej’s painting Pass a Brick from 1950 is addressed to viewers in order to encourage their active participation in the building of the new order. In another of Kobzdej’s paintings, Brick Women from 1950, a smooth wall fills the setting. For Wojciech Włodarczyk, the protagonist of the work is the plastered wall itself, representing the fulfilment of the act of construction.30 The center of the piece is almost entirely filled with the abstract flat surface of the wall, against which the brick women lean.

Another example is a poster recognized as the founding piece of the Polish School of Posters, The Walls of Malapaga by Wojciech Fangor from 1952. The wall serves here as the backdrop for the characters, and to display the film title painted on it, just as in the poster by Nowicki and Sandecka. The function of the wall in this case is to compress emotions, to convey both the content of and the protagonist’s image from René Clement’s film: the eponymous walls of Malapaga – the streets of the city and its people. This is not the only case in which a wall bears a heavy layer of meaning in Fangor’s work – the most famous example is the Socialist Realist painting Figures from 1950, which contrasts a worker couple with a personification of the West, the latter portrayed in front of a backdrop of ruins that clearly symbolize moral bankruptcy, while on the workers’ side massive and stable edifices of the new communist order can be seen soaring.31

The motif of the wall was often employed in the cheerfully optimistic posters promoting the Five-Year Plan. It is invoked as a symbolic building block of the new political order or to mark the border with Western capitalism and imperialism; it makes social distinction more complete. Representations of executions by firing squad are virtually non-existent in Socialist Realism.

As clearly seen in Wróblewski’s painting, the building blocks of the wall are bricks. “Architecture starts when you carefully put two bricks together,”32 Ludwig Mies van der Rohe famously stated. This structural dimension is visible in Wróblewski’s painting – the brickwork is carefully rendered with thick lines, and the color of the bricks is represented correctly in the shadow. The wall looks newly built; the gaps are filled with clean white mortar. Wróblewski therefore paints a beautiful brick wall, a fundamental structure raised by humans, one of the pillars of architecture and civilization, and then confronts it with the fall of humanity.

On the wall, in front of the wall – Wróblewski, Sartre, Derrida

The 1940s marked a turning point and witnessed a change in the awareness of French intellectuals and artists, with existentialism rising in significance and popularity. In 1942, Jean-Paul Sartre published the seminal work of French existentialism Being and Nothingness. Alongside The Plague by Albert Camus, it sought to define the condition of the French intellectual in the moral conundrum caused by the surrender of the country and the nationalistic Vichy regime. Sartre became a leading figure among French intellectuals in the 1940s and, alongside writers such as Roland Barthes, formulated the ethos of the engaged intellectual. “It was engagement in the propagation of the cultural model of a certain formula of engagement, which closely corresponds to what was happening at that time in Poland, where existentialism was making an entry” – as Wojciech Włodarczyk commented.33

In 1939, Sartre published his short story The Wall,34 in which he laid out his concepts of the absurdity of the world, freedom, and responsibility – the fundamental pillars of existential philosophy. The nameless protagonist awaits execution in a prison cell:

I want to be brave but first I have to know… Listen, they’re going to take us into the courtyard. Good. They’re going to stand up in front of us. How many? – I don’t know. Five or eight. Not more. – All right. There’ll be eight. Someone’ll holler ‘aim!’ and I’ll see eight rifles looking at me. I’ll think how I’d like to get inside the wall, I’ll push against it with my back… with every ounce of strength I have, but the wall will stay, like in a nightmare. I can imagine all that. If you only knew how well I can imagine it.35

This short story is an interesting reference for Wróblewski’s Execution against a Wall, although there is no evidence that the painter was familiar with it.36 The painting features a man wearing a red tie. He stands still and straight in the face of imminent death. His absent gaze expresses utter resignation; the thoughts of Sartre’s protagonist could be his own. The painting and the short story share a sense of surreal absurdity and horrific danger. In Sartre’s work, the man seeks to understand and thereby make familiar the experience of death, which by its very nature lies beyond the scope of cognition. “I want to be brave but first I have to know,” he says.37 This paradox was pointed out by Jacques Derrida, who asked “Is my death possible?”38 Derrida wrote about the impossibility of one’s own death: how can it be “my” experience, when “I” am no longer there? If death is the possibility of the impossible, then – going further – it is also the possibility of the appearance of the impossibility of appearing. It is therefore impossible for a subject to establish a relation with their own death, only with the death of another or with the fading away and stages that precede death.39 The death of another person is the only death we can cognize, and it provides the foundation for the experience of “my” death. While painting his Executions, Wróblewski was the first witness and viewer of the executions he devised. I would venture the opinion that in a certain phantasmal way it also allowed him to experience his own death. Derrida’s thought resonates in a particularly interesting way with those of the Executions that portray a number of victims (The Poznań Execution) or those that may be understood as representations of the stages of dying (The Surreal Execution).

Yet, perhaps a different kind of cognition is at stake. The protagonist of The Wall visualizes the imminent event, divides it into subsequent stages, and replays it like a film. He precisely determines the number of soldiers in the firing squad and talks about exactly eight rifles pointed at him. The image is highly cinematic. Perhaps one of the figures in Wróblewski’s piece is a visualization. In such a case, it would be logical to recognize the figure on the left as the actual, real one, and the blue man, on the side of death, as a projection. Does the figure with the red tie, with his eyes turned slightly inwards, imagine what is about to happen? What does he actually see? He may be seeing himself stripped of some of his clothes in the face of death: the shoes, which are a basic item of clothing and a source of human dignity, or the red tie, which may be understood as a symbol of political affiliation.

There is one more passage in Sartre’s short story that powerfully resonates with the context of Wróblewski’s painting:

And since I was going to die, nothing seemed natural to me, not this pile of coal dust, or the bench, or Pedro’s ugly face. Only it didn’t please me to think the same things as Tom. And I knew that, all through the night, every five minutes, we would keep on thinking things at the same time. I looked at him sideways and for the first time he seemed strange to me: he wore death on his face. My pride was wounded: for the past 24 hours I had lived next to Tom, I had listened to him. I had spoken to him and I knew we had nothing in common. And we now looked as much alike as twin brothers, simply because we were going to die together.40

I consider this passage as a highly significant commentary that complements the understanding of the war paintings by Wróblewski, who mentioned the slogan “war debases humans” among the topics of the pieces for the Poznań exhibition.41

Yet, it can be interpreted in two ways. Sartre’s writing features the motif of multiplication, which is also present in Wróblewski’s work. In Execution against a Wall, the executed man is also duplicated, or perhaps rather repeated with an element of nothingness, which is an extremely important element that builds the narrative of the painting. For Piotr Piotrowski, that multiplication, which also occurs in The Surreal Execution, results from horror, which imposes identical masks on the faces of the two men.42 In Sartre’s short story, the other convict “seemed strange […] he wore death on his face.” Commenting on Execution III, where the same figure is also represented a number of times, Piotrowski wrote about “visualization,”43 which I have evoked above. The motif of duality can also be encountered in other works by Wróblewski, although it adopts a different character: there are two celestial bodies glowing above Drowned City (undated). Two figures – the ego and the alter ego, the body and its shadow. Two worlds permeate one another in the artist’s universe; they overlap and co-exist – the blue dead still embrace the living, the burden of their presence is so heavy that it leaves its mark on the survivors.

I propose a different interpretation, however. Bearing in mind Sartre’s short story and Wróblewski’s reflection on the war which strips the subject of dignity and humanity, I am inclined to adopt a more affective understanding. The two men in Wróblewski’s painting do not necessarily have to be the same person, but in the face of death the differences between them disappear and the men awaiting execution become similar to one another: “they wear death on their faces.” This observation raises disgust and fear in Sartre’s protagonist. What ultimately humiliates him is his similarity to other convict. By the wall, all identity is erased by the degrading experience of the ultimate stripping of everything human. The liminal experience of one’s own death – to refer to Derrida – deprives the subject of all individuality; it is no longer possible to recognize them. And although death erases everything personal and particular, and removes the differences between the men, it still fails to unite them.

*

Whereas the other Executions are narratively framed stories or clashes between two stances where – as in Goya’s and Manet’s pieces – the viewer remains an observer (although a certain transgression of that situation is implied by the shadow falling on the painting in Manet’s painting), the situation in Execution against a Wall is more complex. The figures tightly fill almost the entire available space, preventing the viewer from escaping with his or her gaze. The viewer is confronted directly with the situation of execution. I believe that for Wróblewski the painting was not only supposed to affect and influence the viewer, but also offer them a space to act. In Execution against a Wall, the wall limits the field of vision and, akin to an arena or a stage, forces the viewer to participate in the event. It fences off and encloses the shallow space of the painting, reducing pictoriality for the sake of greater situationality. The artist consciously made use of the purely physical properties of the painting, such as the canvas. The flatly represented wall repeats the two-dimensional surface of the canvas; the painting manifests its own materiality.

Wróblewski sought possibly the most dramatic formula of painting that confronted representation after the cataclysm of war, and achieved that effect in various ways in the eight Executions. Execution IV features two figures becoming similar to one another in the liminal experience of death. The death written on their faces places masks on them; they become indistinguishable, united in the face of the extreme situation, albeit their union strips them of subjectivity and dignity.

Bibliography

Baraniewski, Waldemar. “Pamięć obrazów / obrazy pamięci.” In Perspektywa wieku dojrzewania. Szapocznikow – Wróblewski – Wajda. Edited by Anda Rottenberg. Katowice: Muzeum Śląskie w Katowicach, 2018.

Białostocki, Jan. “Temat ramowy i obraz archetypiczny. Psychologia i ikonografia.” In Jan Białostocki, Teoria i twórczość. Poznań: Państwowe Wydawnictwo Naukowe, 1961.

Czekalski, Stanisław. Intertekstualność i malarstwo. Problemy badań nad związkami międzyobrazowymi. Poznań: Wydawnictwo Naukowe UAM, 2006.

Derrida, Jacques. Aporias by Jacques Derrida. Translated by Thomas Dutoit. Stanford: Stanford University Press, 1993.

Dziewańska, Marta. “Andrzej Wróblewski: Antihero.” In Andrzej Wróblewski: Recto / Verso. Madrid: Museo Nacional Centro de Arte Reina Sofia, 2015.

Elderfield, John. Manet and the Execution of Maximilian. New York: Museum of Modern Art, 2006.

Jarecka, Dorota. “Artysta na ruinach. Sztuka polska lat 40. i surrealistyczne konotacje.” Miejsce. Studia nad Sztuką i Architekturą Polską XX i XXI Wieku, no. 2 (2016).

Kordjak, Joanna, Agnieszka Szewczyk, “Just after the War.” In Just after the War. Edited by Joanna Kordjak, Agnieszka Szewczyk. Warsaw: Zachęta – Narodowa Galeria Sztuki, 2015.

Kostołowski, Andrzej. “Ze studiów nad twórczością Andrzeja Wróblewskiego (1927–1957).” Studia Muzealne, vol. 6 (1968).

Pijarski, Krzysztof. “Cut-View of the Week. ‘Documents’ between Propaganda and Working-Through.” In: Just after the War. Edited by Joanna Kordjak, Agnieszka Szewczyk. Warsaw: Zachęta – Narodowa Galeria Sztuki, 2015.

Piotrowski, Piotr. “Wojna i obraz.” In Piotr Piotrowski, Znaczenia modernizmu. W stronę historii sztuki polskiej po 1945 roku. Poznań: Rebis, 2011.

Sartre, Jean-Paul. “The Wall.” In Jean-Paul Sartre, The Wall. Translated by Andrew Brown. London: Hesperus Press, 2005.

Tarabuła, Marta. “Kronika wydarzeń.” In Andrzej Wróblewski nieznany. Edited by Jan Michalski. Kraków: Galeria Zderzak, 1993.

Wróblewski, Andrzej. Postcard to Witold Damasiewicz, manuscript, September 9, 1949, unpublished, archive of Agnieszka Damasiewicz. In Avoiding Intermediary States. Andrzej Wróblewski (1927–1957). Edited by Magdalena Ziółkowska, Wojciech Grzybała. Warsaw: Fundacja Andrzeja Wróblewskiego, Instytut Adama Mickiewicza, Hatje Cantz Verlag, 2014.

Wróblewski, Andrzej. “Komentarz do Wystawy Sztuki Nowoczesnej.” In W kręgu lat czterdziestych, part 2. Edited by Józef Chrobak. Kraków: Stowarzyszenie Artystyczne Grupa Krakowska, 1991.

Wróblewski, Andrzej. “Letter to Anna Porębska (excerpt).” In Avoiding Intermediary States. Andrzej Wróblewski (1927–1957). Edited by Magdalena Ziółkowska, Wojciech Grzybała. Warsaw: Fundacja Andrzeja Wróblewskiego, Instytut Adama Mickiewicza, Hatje Cantz Verlag, 2014.

Ziółkowska, Magdalena, Wojciech Grzybała, eds. Avoiding Intermediary States. Andrzej Wróblewski (1927–1957). Warsaw: Fundacja Andrzeja Wróblewskiego, Instytut Adama Mickiewicza, Hatje Cantz Verlag, 2014.

- See: Andrzej Wróblewski, “Komentarz do Wystawy Sztuki Nowoczesnej,” in: W kręgu lat czterdziestych vol. 2, ed. Józef Chrobak (Kraków: Stowarzyszenie Grupa Krakowska, 1991), 19. ↩︎

- The text is based on the master’s dissertation titled Ceglany mur w Rozstrzelaniu na ścianie Andrzeja Wróblewskiego – moment wizualności [The Brick Wall in Andrzej Wróblewski’s Execution against a Wall – Moment of Visuality], written under the supervision of Dr. Luiza Nader and defended at the Faculty of Management of Visual Culture at the Academy of Fine Arts in Warsaw. I wish to express my utmost gratitude to my supervisor for her extremely valuable remarks and cordial support. ↩︎

- The Executions are the topic of an extremely broad array of bibliographic sources. Given the limited length of this article, I only provide examples of the most important publications: Andrzej Wróblewski w 10-lecie śmierci: referaty i głosy w dyskusji w Rogalinie 4 maja 1967, ed. Irena Moderska (Poznań: Muzeum Narodowe w Poznaniu, 1971); Andrzej Kostołowski, “Z badań nad twórczością Andrzeja Wróblewskiego (1927–1957). Okres do 1949 roku,” Studia Muzealne vol. 6 (1968); Andrzej Wróblewski nieznany, ed. Jan Michalski (Kraków: Galeria Zderzak, 1993); Piotr Piotrowski, “Wojna i obraz,” in: Znaczenia modernizmu. W stronę historii sztuki polskiej po 1945 roku (Poznań: Rebis, 2011); Anna Markowska, Dwa przełomy. Sztuka polska po 1955 i 1989 roku (Toruń: Fundacja na rzecz Nauki Polskiej, 2012); Noit Banai, “Experimental Figuration in a State of Exception,” in: Unikanie stanów pośrednich / Avoiding Intermediary States. Andrzej Wróblewski (1927–1957), eds. Magdalena Ziółkowska and Wojciech Grzybała (Warsaw: Fundacja Andrzeja Wróblewskiego, Instytut Adama Mickiewicza, Hatje Cantz Verlag, 2014); Andrzej Wróblewski: Recto / Verso, eds. Eric de Chassey and Marta Dziewańska (Warsaw: Muzeum Sztuki Nowoczesnej w Warszawie, 2015); Wojciech Szymański, “Kwadratowe koło: Andrzej Wróblewski i nowoczesny realizm socjalistyczny,” in: Socrealizmy i modernizacje, eds. Aleksandra Sumorok and Tomasz Załuski (Łódź: Akademia Sztuk Pięknych im. Władysława Strzemińskiego w Łodzi, 2017); Filip Pręgowski, “Powtórzenie socrealizmu. Malarstwo Andrzeja Wróblewskiego i Jarosława Modzelewskiego,” in: ibid. Among the attempts to formulate new interpretations, I wish to highlight the chapter “Pomiędzy kosmogonią a katastrofą” in Marcin Lachowski’s book. Although Execution against a Wall is not addressed specifically, Lachowski also draws attention to Wróblewski’s pursuit of depicting the individual character of war experience; see: Marcin Lachowski, Nowocześni po katastrofie. Sztuka w Polsce w latach 1945–1960 (Lublin: Wydawnictwo KUL, 2013), 238–265. ↩︎

- Stanisław Czekalski, Intertekstualność i malarstwo. Problemy badań nad związkami międzyobrazowymi (Poznań: Wydawnictwo Naukowe UAM, 2006). ↩︎

- Andrzej Wróblewski, (3 x YES), undated, watercolor, ink, paper, 21.1 × 29.7 cm, private collection, in: Ziółkowska and Grzybała, Avoiding Intermediary States, 210. ↩︎

- In the sense of a whole that results from the combination of various elements. ↩︎

- See: two missing self-portraits from 1949, in: Ziółkowska and Grzybała, Avoiding Intermediary States, 199. ↩︎

- The Executions that feature the figure of a small boy portray him as half-naked, shirtless, and thus contrasted with the fully clothed adults. Attire can therefore be understood in this context as an emblem of adulthood, while nudity may stand for childhood and innocence. The boy in the Executions does not perish – he is a witness. ↩︎

- The exception is found in Executed Man, also known as Execution with a Gestapo Man and Execution VI. ↩︎

- Wróblewski, “Komentarz do Wystawy Sztuki Nowoczesnej,” 19. ↩︎

- See: Krzysztof Pijarski, “Cut-View of the Week. ‘Documents’ between Propaganda and Working-Through,” in: Just after the War, eds. Joanna Kordjak and Agnieszka Szewczyk, trans. Marcin Wawrzyńczak (Warsaw: Zachęta – National Gallery of Art, 2018), 99–103; Joanna Kordjak and Agnieszka Szewczyk, “Just after the War,” in: ibid., 5–20. ↩︎

- See: Lachowski, Nowocześni po katastrofie, 248–249. ↩︎

- Piotrowski, Znaczenia modernizmu, 16–20. ↩︎

- Quoted from: Marta Tarabuła, “Kronika wydarzeń,” in: Michalski, Andrzej Wróblewski nieznany, 278. ↩︎

- The topic was first discussed by Andrzej Kostołowski; see: Andrzej Kostołowski, “Z badań nad twórczością Andrzeja Wróblewskiego (1927–1957). Okres do 1949 roku,” Studia Muzealne vol. 6 (1968). ↩︎

- Jan Białostocki, “Temat ramowy i obraz archetypiczny. Psychologia i ikonografia,” in: Jan Białostocki, Teoria i twórczość (Poznań: Państwowe Wydawnictwo Naukowe, 1961), 160. ↩︎

- Kostołowski, “Z badań nad twórczością Andrzeja Wróblewskiego,” 140. ↩︎

- Marta Dziewańska, “Andrzej Wróblewski: Antihero,” in: Andrzej Wróblewski: Recto / Verso (Madrid: Museo Nacional Centro de Arte Reína Sofia, 2015), 25. ↩︎

- John Elderfield, Manet and the Execution of Maximilian (New York: Museum of Modern Art, 2006), 19. ↩︎

- Ibid., 20. ↩︎

- Piotrowski, Znaczenia modernizmu, 19. ↩︎

- Even more conspicuous references to Goya and Manet can be observed in Picasso’s later painting Massacre in Korea from 1951. ↩︎

- Wróblewski wrote about Picasso, demonstrating knowledge of his work, for instance on January 22, 1948, see: Ziółkowska and Grzybała, Avoiding Intermediary States, 87. The catalog of the artist’s posthumous exhibition in 1958, Andrzej Wróblewski. Wystawa pośmiertna (Kraków: ZPAP, 1958), features a mention of Picasso in Wróblewski’s notes from 1956: “I like the changeability of the artist’s personality – such as Picasso’s – and the modern type of artistic work, which does not consist only of making individual masterpieces, but in setting a certain sequence of artworks that combine to form today’s counterpart of a masterpiece.”; quoted from Ziółkowska and Grzybała, Avoiding Intermediary States, 620. Picasso’s paintings were reproduced in the influential weekly Przekrój, see: Pijarski, “Cut-View of the Week,” 238. ↩︎

- See: Dorota Jarecka, “Artysta na ruinach. Sztuka polska lat 40. i surrealistyczne konotacje,” Miejsce. Studia nad Sztuką i Architekturą Polską XX i XXI Wieku no. 2 (2016), 17. ↩︎

- v ↩︎

- The official website of Andrzej Wajda, who was Wróblewski’s friend, mentions this work: “Grottger was the first Polish painter I became familiar with as a child. The monograph of this artist penned by Antoni Potocki was lying on the table at the home of my grandparents […]. I remembered the Warsaw series particularly well. A year ago, I managed to get hold of this series at one of Kraków’s antiquarian bookshops […] How could I have known then, being a child, looking with delight at the panels of The First Victim or The Closing of the Churches, that half a century later I should witness similar events, and again in Warsaw.”; quoted from “Artur Grottger, The First Victim (from the cycle Warsaw I), 1861”, http://www.wajda.pl/pl/lubi/lubi04.html (accessed September 20, 2019). ↩︎

- I would like to thank Wojciech Włodarczyk for drawing my attention to this and several other aspects; Professor Włodarczyk lectured during the Master’s seminar at the Faculty of Management of Visual Culture of the Academy of Fine Arts in Warsaw in 2017. ↩︎

- Kordjak and Szewczyk, Just after the War, 25. ↩︎

- Celnikier made two attempts to represent the ghetto theme. The first version from 1949, to which I refer, forms part of the collection of the Jan Dekert Lubusz Museum in Gorzów Wielkopolski. The second, unfinished painting was presented at the Arsenal exhibition in 1955 (and is currently in the collection of the Yad Vashem in Jerusalem). ↩︎

- Włodarczyk, Master’s seminar lecture, Academy of Fine Arts in Warsaw, 2017. ↩︎

- See: Karol Sienkiewicz, “Wojciech Fangor, ‘Postaci’”, https://culture.pl/pl/dzielo/wojciech-fangor-postaci (accessed September 20, 2019). ↩︎

- Christian Norberg-Schulz, “Talks with Mies van der Rohe,” L’Architecture d’Aujourd’hui no. 79 (1958), 100. ↩︎

- Włodarczyk, Master’s seminar lecture, Academy of Fine Arts in Warsaw, 2017. ↩︎

- Jean-Paul Sartre, “The Wall,” in Jean-Paul Sartre, The Wall, trans. Andrew Brown (London: Hesperus Press, 2005). ↩︎

- Ibid., 12. ↩︎

- The Polish translation of The Wall was first published in 1958 by the Czytelnik publishing house in its Nike series. Wróblewski would therefore have to have read it in the original version to become familiar with the text. An abundance of information about his reading is offered by his diaries, in which he noted the films he watched and sometimes also the books he read. Yet, they feature no mention of The Wall. ↩︎

- Sartre, “The Wall,” 12. ↩︎

- Jacques Derrida, Aporias by Jacques Derrida, trans. Thomas Dutoit (Stanford: Stanford University Press, 1993, 21–22. ↩︎

- Ibid., 76. ↩︎

- Sartre, “The Wall,” 14. ↩︎

- Andrzej Wróblewski, postcard to Witold Damasiewicz, manuscript, September 9, 1949, archive of Agnieszka Damasiewicz, in: Ziółkowska and Grzybała, Avoiding Intermediary States, 264–265. ↩︎

- Piotrowski, Znaczenia modernizmu, 19. ↩︎

- Ibid., 18. ↩︎

Magdalena Gemra

Graduate of the Institute of Art History at the University of Warsaw, the Academy of Fine Arts in Warsaw, and the École des Hautes Études en Sciences Sociales in Paris. Gemra runs the studio of Miroslaw Balka and has been involved in dozens of the artist’s individual shows, including CROSSOVER/S at the Pirelli HangarBicocca in Milan and DIE SPUREN at the Morsbroich Museum in Leverkusen (2017). Gemra has also worked on the archives of artists, including Miroslaw Balka, Katarzyna Kozyra, and Andrzej Wróblewski.