Tytuł

Triple Exclusion and Fierce Determination. Case Studies of Dragica Čadež & Duba Sambolec

https://www.doi.org/10.48285/ASPWAW.24501611.MCE.2021.7.8

http://miejsce.asp.waw.pl/triple-exclusion-and-fierce-determination-case-studies-of-dragica-cadez-duba-sambolec/

Abstrakt

The essay focuses on the life and work of two important female artists from Ljubljana, Slovenia, Dragica Čadež (b. 1940) and Duba Sambolec (b. 1949), who have both been influential in the Slovenian and Yugoslav cultural milieu, but at the same time have both faced exclusion from the dominant canons of local art history. Furthermore, it outlines some general impulses behind the apparent lack of gender equality in the world of art in Slovenia and Yugoslavia before and after 1989, as well as crucial geopolitical circumstances that have often kept female artists on the margins of the art scene. Besides local (gender) and international (geographic) marginalisation, Čadež and Sambolec have also been dis-

advantaged for being unable to store and preserve their large-scale works, while museums were not interested in (or incapable of) their acquisition. In order to point out the symptoms of systemic exclusion that have prevented many female artists from receiving their deserved critical acclaim, the essay looks into the distinctive artistic practices of

both artists and tries to relate them to the significant projects and turning points of their careers. The text is based on available art historical sources, as well as on in-depth interviews with both artists.

DOI

Triple Exclusion and Fierce Determination. Case Studies of Dragica Čadež & Duba Sambolec

Exclusion

The following essay focuses on the artistic practices of two important female artists from Ljubljana, Slovenia, Dragica Čadež (b. 1940) and Duba Sambolec (b. 1949), who have both been influential in the Slovenian and Yugoslav cultural milieu, while Sambolec has operated internationally as well. However, they have both faced marginalisation and exclusion from the dominant canons of local art history. Ontological exhibitions of Slovenian sculpture have often bypassed 1 both artists despite the fact that they have achieved a certain acclaim. Nevertheless, they have often experienced hardship in relation to state institutions and thus official historiography.

Their stories coincide with general issues regarding the lack of gender equality in the world of art in Slovenia and Yugoslavia before (and after) 1989, and with geopolitical circumstances that often kept artists from Yugoslavia on the margins of the international art scene.

Besides local (gender) and international (geographic) marginalisation, Čadež and Sambolec were also disadvantaged for being unable to store and preserve their large-scale works, while museums were not interested in (or incapable of) their acquisition. However, nowadays one could perceive their careers as success stories, as they managed, with great self-initiative, to maintain their practices, thus defying their underrepresentation. Their struggle to gain recognition, enable production conditions and secure financial resources reveal symptoms of systemic exclusion that have prevented many local (female) artists from deserved critical acclaim in the second half of the 20th century.

The socio-political and temporal context

The socio-political and cultural context of Yugoslavia was peculiar from the global perspective, especially in the period after 1960, when

this socialist country managed to establish its own political system and ideology. Politically, it was based on anti-imperialism, economically – on the principles of the welfare state and self-management, and culturally – on openness to different influences. It had a special status, as it maintained close ties with Eastern and Western Bloc countries, while being a founding member of the Non-Aligned Movement. From the 1960s, Yugoslavia was pretty much a free country, with citizens being able to travel abroad undisturbed, which affected several generations of artists in the 1970s and 1980s. In terms of cultural policy, the country leant towards the West, and in the field of visual art close ties were established and maintained with several centres of power, thus making international modernist currents a prevailing influence.

These circumstances allowed the establishment of a vibrant art scene and laid the foundation for a strong infrastructure of institutions, journals and festivals. By the mid-1960s, new generations of artists emerged on the scene who did not necessarily fit the norms

and formulas of representational art. Young sculptors were not in a position to become part of the establishment as their practices did

not coincide with the requirements for state commissions, i.e. to conceive and execute ideologically charged monuments to war and revolution. Their turn to often amorphous structures, organic shapes and geometric purity brought highly ambivalent results. 2 Young artists were discovering new possibilities in the formal aspects of art, while often dealing with engaged subject matters, assured by freedom of expression – with certain exceptions and unwritten rules.

Each of the six Yugoslav federal republics established and nurtured its own publicly funded scene and infrastructure. Despite the principle of public funding being utterly democratic, it often led to the significant concentration of power in a few individuals. Therefore, in Slovenia and Yugoslavia, a handful of people dictated cultural policy and controlled historiography.

The underrepresentation of Čadež and Sambolec was a result of these circumstances, which continued well beyond 1989 and radically impacted their artistic endeavours. However, the artists made strong networks across Yugoslavia which enabled them to work and show that work over a fairly large territory. That is why the violent breakup of Yugoslavia in 1991 turned out to be so terrible for so many artists. Čadež stated, that ‘it felt like being locked in a cage’ 3 in the early 1990s, when she, and many of her colleagues, were constrained to work in the small territory of Slovenia.

Despite these circumstances, both artists managed to reinvent themselves several times throughout their careers, demonstrating resilience and stubbornness. Neither of them had the privilege of becoming a full-time artist, but had to work in different jobs in order to sustain

themselves and their practices. They both found jobs in education, but were not given the privileges of ‘state artists’ who were granted safe, lifetime positions at the Academy of Fine Arts in Ljubljana. Additionally, their works were rarely acquired by art institutions, which rendered their practices financially unsustainable and sidelined them in art historiography. Moreover, a number of their works were lost or destroyed due to the inability to properly store, preserve and maintain them. However, their practices fill certain gaps in the regional history of art. 4

Even though Yugoslavia was a respected and relevant state on the global arena, its geopolitical position and specific history kept it on the

margins of the world of art. One of the reasons for that was the lack of financial capability, as the living standard was significantly lower than in the countries of the West. As Sambolec pointed out, the issue in the 1970s and 1980s was not political repression, but the poor financial situation of ordinary Yugoslavs, making it hard to travel, live or work abroad. 5 But there were other opportunities in a state with an economic system of self-management in which, at least in theory, workers were owners of their companies. Sambolec, for instance, managed to collaborate with the collectives of several factories where she manufactured her large-scale works.

One of the pressing issues of Slovenian and Yugoslav society, however, was traditional patriarchal hegemony, which persisted throughout the socialist era and beyond, despite the official policy of gender equality. But there was a distinction between theory and practice. Therefore, in the 1970s and 1980s, the Slovenian art scene was male-dominated (that has changed in the past twenty years) as all key institutional and academic positions were only rarely made available to women. To this day, all professors at the sculpture department of the Academy of Fine Arts in Ljubljana have been men.

Like many artists of that generation, Čadež and Sambolec were influenced by Western artistic canons but they managed to develop their

own variations of so-called high Modernism. Both trained as sculptors, they changed the classic perception of the artwork, creating overwhelming spatial installations where sculptures became ambience, and empty spaces became as important as sculptures. The Modernist style and aesthetics was dominant and had been widely accepted in the Yugoslav cultural milieu since the 1960s, however, the turn to hitherto unknown forms of expression would not immediately be acknowledged by the institutions. That was one of the reasons for the relative non-acceptance of both artists locally, and the best way to explore the causes for their poor visibility is to take a closer look at their artistic practices and their reception.

Dragica Čadež

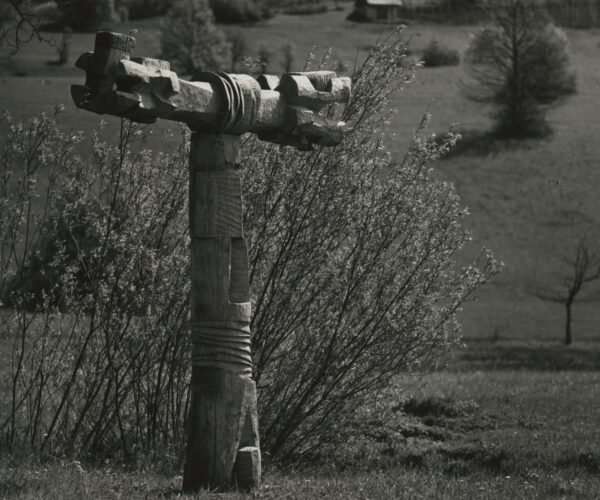

In the early 1960s, the first generation of artists who graduated from the Academy of Fine Arts in Ljubljana broke away from the traditional perception of sculpture. Dragica Čadež completed her postgraduate studies in sculpture in 1965 and started working in a distinctively Modernist style, influenced by artists such as Henry Moore and Barbara Hepworth. Her works became stylised, merging figurative and abstract forms, like in the series Symbol T (Simbol T, 1965–1966), where the human figure was transformed to the ultimate limit. A monumental variation of that work was made at the ‘Forma viva’ International Symposium of Sculptors (Mednarodni simpozij kiparjev) in Kostanjevica na Krki in 1966, becoming her first large-scale wooden sculptural piece.

In 1968, Čadež made a significant creative leap in her practice when she turned to geometrical art, following the zeitgeist of concurrent minimalist art, and became part of the group Neokonstruktivisti (Neoconstructivists), an informal collective active in the period 1968–1972, connecting artists of the new generation. 6 Čadež’s works of that period defied the essence of sculptural media, i.e. the direct relation to materiality. Instead, they were made through industrial process, in order to produce symmetrical, rectangular and geometric shapes, where traces of material were hidden behind the smooth surfaces of designed objects. Despite successful exhibitions in Zagreb and Belgrade, her practice was not well received in Ljubljana. The artist believes that herself and the group were not widely accepted because their practice was relatively alien to the dominant currents of that time. 7

Her quest for visual symmetry and concealed materiality was later replaced by more organic and brute expression. By the mid1970s, her sculptures had turned into ambient and spatial installations, while they also became more engaged in terms of subject matter. However, the reason for going back to manual sculpting was conditioned by other difficulties as well; production of geometric works required the involvement of professional carpenters which eventually became financially unsustainable. Instead, she started using a chainsaw in her creative process in order to make distinctive wooden textures and surfaces. Her sculptures and installations began to explore spatial relations, variations of the human figure and the resilience of human beings in relation to natural elements. 8

In 1986, she received the prestigious national Prešeren Awardfor the series Associations of Pompeii (Asociacija na Pompeje), in which she went back to explore figurative, yet intensely expressive sculpture in order to address the notion of immense catastrophe. Despite growing

success and acclaim, the reality was different, as she worked a full-time teaching job which limited her creative work. As she did not work on commission or for the art market, her studio soon became too small to store her earlier works, some of which were therefore reused, destroyed or damaged, thus disappearing from the collective memory. In 1996, she took the initiative to preserve her oeuvre and donated her works to GBJ – Božidar Jakac Art Museum, saving them from destruction and oblivion. Furthermore, her public works did not fare any better. Mainly made out of wood, they were very fragile when exposed to natural elements outdoors, and therefore most of the large-scale sculptures have decayed and been removed. Moreover, her name nearly disappeared from the cultural milieu of the former Yugoslavia after its turbulent disintegration and after a period of her extensive work in the country in the 1970s and 1980s. During those decades a huge network of artistic manifestations, such as sculptural symposia, art colonies and other festivals, was established across the state.

At the turn of the 1990s, new tendencies of contemporary art reached Slovenia and Yugoslavia, and thoroughly transformed the world of art, introducing more direct, relational, media-based and interdisciplinarynpractices. Some artists from the former East, including Yugoslavia, became internationally acclaimed for their artistic accounts of the war and post-socialist condition. Čadež, however, kept her practice in frames of Modernist ideas of communicating with forms – transforming the material and challenging the perception of the viewer. In the 1990s, she created some of the most complex and visually challenging spatial installations, addressing fundamental existential questions, such as Lignified Shadows (Olesenele sence, 1998) and The Big Closed Doors (Velika zaprta vrata, 1994), continuing her crude treatment of wood, with deep furrows and burned surfaces.

The third obstacle was related to her artistic media and materials that were expensive to produce and difficult to store. Her large-scale

wooden works and spatial installations were made of numerous fragile elements, which often rendered them unsuitable for museum collections. However, seen from the perspective of the concurrent international Modernist movements, she belonged to the generation that was addressing the relationships between objects and spaces. In Čadež’s own words, sculpture in many ways resembles architecture in the treatment of space; like architecture, sculpture creates a shell and has its internal space, thus blurring the line between interior and exterior. 9

Duba Sambolec

In the mid-1970s, Duba Sambolec emerged on the art scene in Ljubljana, adopting a distinctive, almost Postmodern approach of direct engagement. While on an undergraduate course at the Academy of Fine Arts in Ljubljana, she created and showcased a series of representational sculptures resembling hyperrealism, using cheap and inconspicuous materials, such as ready-made objects, polyester resin and colour. The sculpture Working Class Marching (Delavski razred na pohodu, 1976) was a colourful, realistic depiction of the underclass – one of her models was the cleaning lady at the academy – pointing at the obvious absurd: the stratification of society in an egalitarian socialist state. Moreover, the work was a reaction to the rigid, ‘classicist’ curriculum of the state art academy. 10

She also adopted feminist ideas in order to confront the patriarchal society that remained traditionalist, despite the socialist paradigms of gender equality. The structure of the academy professors, who were predominantly male, reflected that phenomenon. In the specific circumstances of socialist Yugoslavia, she developed a distinctive and constantly mutating artistic practice, marked by an ongoing preoccupation with forms, spatial relationships, social issues and sensibilities. 11

In the late 1970s, influenced by Minimal art, Land art and various Modernist currents, she started working on ambitious large-scale

spatial installations where the notion of the single sculptural piece was deconstructed; instead, diverse elements constituted objects in relation to each other, and in relation to the space. Her site-specific installations worked differently and more surprisingly in every space they inhabited. 12 In 1979, an influential exhibition took place at the Student Centre Gallery (Galerija SC) in Zagreb, where her three spatial installations transformed the venue. The installation Ambient I (Ambient I, 1979) made an impact by introducing contradictions between selected materials and their ability to affect the perception of the viewer. 13

In her works, Sambolec has commonly juxtaposed different materials to incite unexpected sensations and associations, showcasing linear and geometric harmony as part of the everyday experience in an over-designed world. Despite it addressing topical formal questions and subject matters, the art institutions in Ljubljana did not fully accept her practice, once again considering unusual and alien. However, she got a better reception in other Yugoslav cities, while at the same time she also exhibited internationally, but in her home town she had to rely on her own resources.

In 1980, she self-organised an outdoor sculptural exhibitio in Ljubljana showcasing several large-scale installations in a public space in order to address the clumsy and incomplete urbanism of Ljubljana. The sculpture Diagonals (Diagonale), which was placed on

a square in front of the Museum of Modern Art Ljubljana (Moderna galerija Ljubljana) marked the point of disruption of the old promenade. Namely, the walkway that used to lead from the main square to the city park in a straight line, was abruptly interrupted by a new road and railway. The sculptures were manufactured in the Litostroj factory, a large state production facility for heavy machinery, where the artist found support in manpower, service and material. Likewise, she collaborated with several other factories across Yugoslavia.

Although Sambolec explored concepts in the context of high Modernist currents, her approach has been commonly seen as Postmodern; she used formal tools according to conceptual needs and she did not pursue a recognisably personal style but constantly shifted her artistic

position, interests and expressive accent. Her practice has therefore always been prone to change and development. After her minimalist period, she became interested in so-called soft sculptures, resorting to unusual materials to create unsettling objects that seemed familiar and yet so alien.

In the 1980s, her work achieved international acclaim which resulted in direct invitations to two highly important biennials; in 1985 she was invited to the São Paulo Biennial, where she created entirely new sculptures due to the inability to transport her existing works. In 1988, she was invited to the Venice Biennial’s ‘Aperto’, an international exhibition curated by the international selector Dieter Ronte, where she showcased her overwhelmingly monumental recent pieces that premiered the same year at her first major exhibition in the Museum of Modern Art Ljubljana. 14

The installation Sky–Earth (Nebo-zemlja, 1987–1988) concerned the contradiction of shapes and angles, a diversion from the expected order of things; the sharp pointed pyramid confronted the soft-rounded surface of the upside down dome, made out of steel and highly polished brass. The work catapulted the artist onto the international art scene, however, the reality in the background was much less ideal. In both cases, by accepting direct invitations she bypassed local decision-makers, and was consequently left without financial support. Instead, she had to work on tight budgets and invest her own time and resources to manage the production.

After the international breakthrough, local museums were not interested in acquisitions, and her sculptures were left without adequate

storage; they remained in the Litostroj factory, where they were, in the course of later privatisa tion, eventually lost or destroyed. In 1992, she took the position of professor and head of the sculpture department at the Trondheim Academy of Fine Arts and later at the National Academy of Fine Arts, Oslo, Norway, where her artistic practice resumed in changed circumstances. She continued to explore objects and spatial installations, but she also made engaged drawings, collages, videos and performances, in search of the sensuality of materials, scale of objects in relation to the body, and the relationship between architecture, object and the visitor. 15

In 2007, she decided not to repeat her previous mistake, and so donated her works from the period 1993–2005 to the Museum of

Contemporary Art (Muzej suvremene umjetnosti) in Zagreb, a gesture that was crowned with the exhibition ‘Object Without Dignity’

(‘Predmet bez dostojanstva’, 2012). Despite the continuity and international acclaim, her work remained outside mainstream art historical discourses in Slovenia, where her exclusion is manifested by the (in)accessibility of her works and lack of relevant analyses.

Conclusion

The stories of both artists, Čadež and Sambolec, are rather similar, as neither of their artistic practices have been properly evaluated, while

many works have not been preserved. Even though they do not belong to the same generation or artistic circles, they both produced large-scale spatial pieces defying traditional notions of sculpture. As pioneers of contemporary sculpture in Slovenia they often ran into structural issues, like the rigid systematisation of artistic currents, inadequate technical abilities of museums, and inconsistent and arbitrary art historiography.

Furthermore, they were both disadvantaged in terms of gender as, at that time, the art scene in Slovenia and Yugoslavia was still overwhelmingly male-dominated. Despite their artistic strength and acclaim, they had unequal opportunities in terms of their academic careers, institutional support and public visibility. They eventually became established, but they had to earn it the hard way. However, their bodies of work were groundbreaking as they, in one way or another, made a crucial connection between the principles of late Modernism and Postmodernism; in Slovenia and Yugoslavia, there seems to be a sharp boundary between the two. However, in the past four decades these currents have been developing simultaneously, often overlapping and supplementing each other. Society, as well as art has always developed in a gradual process.

Bibliography

- Brejc, Tomaž, Duba. Risbe, skulpture / Dravings [sic] – Sculptures, exh. cat. (Ljubljana, 1983)

- Brejc, Tomaž, Luč neba in sol zemlje / The Light of Sky and the Salt of Earth, exh. cat. (Ljubljana: Moderna galerija Ljubljana, 1988)

- Colner, Miha, conversation with Dragica Čadež, 15 February 2021, author’s archive

- Colner, Miha, conversation with Duba Sambolec, 26 February 2021, author’s archive

- Colner, Miha, Dragica Čadež: ‘Zgodba o lesu in glini’, GBJ blog, 21 January 2021 <https://galerija-bj.blog/2021/01/19/dragica-cadez-zgodba-o-lesu-in-glini/> [accessed 29 April 2021]

- Domjan, Alenka, ed., Kiparstvo danes. Komponente, stičišča in presečišča /Sculpture Now: Components, Junctures and Intersections, exh. cat. (Celje: Centre for Contemporary Arts, 2010)

- Protić, Miodrag B., Skulptura XX veka, ed. by Andro Mohorovičić (Beograd: Izdavački zavod Jugoslavija, 1982)

- Sambolec, Duba, ‘The Place Rooms, Things and People’, in Predmet bez dostojanstva. Donacija Dube Sambolec Muzeju savremene umjetnosti Zagreb / Object Without Dignity: Duba Sambolec Donation to the Zagreb Museum of Contemporary Art, exh. cat. (Zagreb: MSU Zagreb, 2012), pp. 21–23

- Čadež and Sambolec are mentioned in the catalogue of the exhibition ‘Sculpture Now. Components, Junctures and Intersections’ (‘Kiparstvo danes. Komponente, stičišča in presečišča’), curated by

Tomaž Brejc, Alenka Domjan, Jiři Kočica and Polona Tratnik, which took place from 10 September to 10 October 2010 at the Gallery of

Contemporary Art (Galerija Sodobne Umetnosti) in Celje. However, the two artists were not part of the show. See Kiparstvo danes. Komponente, stičišča in presečišča / Sculpture Now: Components, Junctures and Intersections, exh. cat., ed. by Alenka Domjan (Celje:

Centre for Contemporary Arts, 2010). ↩︎ - Miodrag B. Protić, Skulptura XX veka, ed. by Andro Mohorovičic (Beograd: Izdavački zavod Jugoslavija, 1982), p. 103. ↩︎

- Miha Colner, conversation with Dragica Čadež, 15 February 2021, author’s archive. ↩︎

- Miha Colner, Dragica Čadež: ‘Zgodba o lesu in glini’, GBJ blog, 21 January 2021 <https://galerija-bj.blog/2021/01/19/dragica-cadez-zgodba-o-lesu-in-glini/> [accessed 29 April 2021]. ↩︎

- Miha Colner, conversation with Duba Sambolec, 26 February 2021, author’s archive ↩︎

- Dragica Čadež, Drago Hrvacki, Tone Lapajne, Slavko Tihec, Dušan Tršar, Vinko Tušek. ↩︎

- Miha Colner, conversation with Dragica Čadež. ↩︎

- Miha Colner, Dragica Čadež, ‘Zgodba o lesu in glini’. ↩︎

- Miha Colner, conversation with Dragica Čadež. ↩︎

- Miha Colner, conversation with Duba Sambolec. ↩︎

- Tomaž Brejc, Duba. Risbe, skulpture / Dravings [sic] – Sculptures, exh. cat. (Ljubljana, 1983), p. 4. ↩︎

- Tomaž Brejc, Luč neba in sol zemlje / The Light of Sky and the Salt of Earth, exh. cat. (Ljubljana: Moderna galerija Ljubljana, 1988), p. 6. ↩︎

- Ibidem, p. 7. ↩︎

- Miha Colner, conversation with Duba Sambolec. ↩︎

- Duba Sambolec, ‘The Place Rooms, Things and People’, in Predmet bez dostojanstva. Donacija Dube Sambolec Muzeju savremene umjetnosti Zagreb / Object Without Dignity: Duba Sambolec Donation to the Zagreb Museum of Contemporary Art, exh. cat. (Zagreb: MSU Zagreb, 2012),

pp. 21–23 (p. 21). ↩︎

Miha Colner

Miha Colner is an art historian who works as a curator at GBJ—Božidar Jakac Art Museum in Kostanjevica na Krki, Slovenia. He is also active as a lecturer and publicist, specializing in the fields of photography, graphic arts, moving images and various forms of (new) media art. In 2017–20, he curated the programme of the Švicarija Creative Centre, an arts venue managed by MGLC—International Centre of Graphic Arts, Ljubljana. He worked as a curator (2006–16) at the Photon Centre for Contemporary Photography in Ljubljana. Since 2005, he has published articles in newspapers, mag- azines, and professional journals, as well as posting them in his blog. He lives and works in Ljubljana and Kostanjevica na Krki.