Tytuł

Little Material, Lot of Thought. Margit Szilvitzky’s Early Works in the Context of the Hungarian ‘New Textile’ Movement

https://www.doi.org/10.48285/ASPWAW.24501611.MCE.2021.7.11

http://miejsce.asp.waw.pl/little-material-lot-of-thought-margit-szilvitzkys-early-works-in-the-context-of-the-hungarian-new-textile-movement/

Abstrakt

The focus of my paper is the work of the artist Margit Szilvitzky (1931–2018) and the position of the Hungarian “experimental textile” movement in the history of the region’s neo-avantgarde art. The textile-based collages, objects and installations created by Szilvitzky, who started her career as a fashion designer in the 1950s, made her one of the leading figures of the “new textile” movement in Hungary starting from the Textile/Wall Image exhibition (1968) throughout the 1970s to the early 1980s. She also became a regular participant at international exhibitions and biennials, while also obtaining a significant position as a professor at the University of Applied Arts, organizing a Bauhaus-inspired “preliminary course” composed of studies of form and structure.

Partly in connection with the new generation of fibre art emerging in Poland, her early pieces used applications and embroidery. In the mid-70s she discovered the folded white canvas, inspired by Joseph Albers’ famous paper exercises, as a medium to the visual representation of thought processes. She also intended to explore the possibilities of space, joining the international trend of post-war abstraction that allowed a central role for textiles.

My paper aims to analyse her work especially in an international context, but also intends to give an insight into the field of Hungarian fibre art and its institutional background through studying the system of the Szombathely Textile

Biennials and the textile symposia in Velem. Szilvitzky was one of the main driving forces behind these events and a regular exhibitor at the biennials. Szilvitzky’s generation contributed largely to spatial textiles (fibre art) becoming a noteworthy area for Hungarian neo-avantgarde art. While analysing the institutional and theoretical aspects of the textile movement Szilvitzky was part of, I aim to explore the position of the Hungarian “experimental textile” movement. While fighting for its emancipation as a form of art instead of a craft, “new textiles” functioned at the periphery of political attention, under less severe ideological and bureaucratic control than the fine arts, also because it was practised mainly by female artists in the mostly male-dominated official and even non-official art scene.

DOI

Little Material, Lot of Thought

Margit Szilvitzky’s Early Works in the Context of the Hungarian ‘New Textile’ Movement 11

Margit Szilvitzky’s (1931–2018) work is inseparable from the proceedings and formulation of the Hungarian ‘new textile’ movement, which resonate with the international developments that affected this field. Szilvitzky’s oeuvre makes for the profile of a versatile artist who also produced a significant body of theoretical work. 22 Her oeuvre seems to follow the evolution of progressive tendencies in the second half of the twentieth century, from abstraction to minimal and conceptual tendencies, and eventually to painting. She worked as a fashion designer – also an expert in the history of clothing and traditional costumes – before she began to experiment with fabric. Her work in teaching, based on Bauhaus principles, as a faculty member of the Academy of Applied Arts (today, the Moholy-Nagy University of Art and Design) was always closely connected to where she was in her art, and attested to a kind of creative energy that regarded teaching itself as an artistic activity. Szilvitzky was virtually a constant participant of the Wall and Spatial Textile Biennials (Fal- és Tértextil Biennálé) and the Miniature Textile Biennials (Miniatűrtextil Biennálé) of Szombathely. She was also among the artists credited for laying down the foundations of the Biennials of Industrial Textile Art (Ipari Textilművészeti Biennálé) and establishing the Textile Art Workshop of Velem (Velemi Textilművészeti Alkotóműhely). She was a regular participant in international exhibitions of Hungarian textile/fabric/fibre art, also taking part in several graphic and artists’ book shows. She held solo appearances in Helsinki, Rome, Voorburg, at Műcsarnok/Kunsthalle Budapest, at the King Stephen Museum of Székesfehérvár and the Kunsthalle Szombathely, among other venues. She was a recipient of the titles of Artist of Merit and Artist of Excellence, as well as the Order of Merit of the Hungarian Republic. However, her work is missing from its merited position in the domestic and international canon. This short study – borrowing its title from Leena Manula’s article about Szilvitzky’s 1977 show in Helsinki 3 – aims to outline the most important aspects of her work and to provide an overview of the context of her activities in the Hungarian ‘new textile’ movement. My aim is also to try to draw international attention to Hungarian textile/ fabric art as a possible field that can be embraced in the re-evaluation process of progressive art tendencies in communist Central Europe.

I

The renewal of textile art is rooted in the emancipative aspirations within the applied arts, which sought to elevate it from the position of a handicraft to the status of ‘high art’, and secondly, the transformation of the fine arts, which also entailed its ‘expansion’ into the domain of everyday life and visual culture. Soft materials also included textiles, and from pop art to minimalism and conceptualism, fabric art – in part, also thanks to the attention of the feminist movement, women’s art to textile art and needlework, as well as to activities and experiments taking place previously in the weaving workshops of the historical avant-garde –gained an increasingly defined, fundamental role among the many forms of expression in fine arts. The English term ‘fibre art’ – concentrating on the unique properties of the fibre, which could be different from the traditional elements of textile works – became a familiar word in the vocabulary of post-war art. In the Hungarian context, the most commonly used terms are, when translated into English, experimental textiles or, referring to the very differing tendencies that were present in this field, simply ‘new textiles’.

Artists from the Eastern Bloc played a notable role in the events that formed the history of textile/fibre art already at the first edition of the Lausanne International Tapestry Biennial in 1962. The change in traditional tapestry – which, following Jean Lurçat’s vision regarding shifting tapestry out from its subordinate position to painting 4 and leading to the launch of the Lausanne Biennials – recognised its potential in mural genres, but stuck with the two-dimensional space. However, Polish artists like Magdalena Abakanowicz, Jolanta Owidzka and Wojciech Sadley, besides the Croatian-born Jagoda Buić and the Jacobi couple of Romanian origin, had already diverged from Lurçat’s concept in the materials they used and in their aim to gradually take over the three-dimensional space. 5 Their intentions were similar to the American artists connecting Bauhaus with Pre-Columbian traditions (Ed Rossbach, Lenore Tawney, or the younger Sheila Hicks), and already in 1969, MOMA’s Wall hangings 6 exhibition proved that their works could be regarded together. For Szilvitzky and her colleagues, Polish fibre art was an example to follow. However, it is also noteworthy that Szilvitzky herself discovered Hicks’ work during a visit to Paris in 1964 7 and considered it as one of the main inspirations in the decades to follow.

Hungarian textile/fabric art did not get the extensive international recognition Polish art did, but the artists’ aspirations and the authorities’ attitude towards it were similar to those in Poland. Even the official view of the Polish textile revolution in Hungary regarded textile as an ‘apolitical’ area. The ‘apolitical’ nature of textile art seemed to be enhanced by the presence of female artists in the field, considered ‘harmless’ by members of the official and art scenes. Following Polish art’s international success, even the Hungarian authorities deemed textile/fabric art worthy of support. At the same time, the success of Polish fabric art would have been unthinkable

without the help of Poles living abroad and the infrastructure established by the Swiss and French gallery system, something that Hungarian artists did not get to the same extent. 8 However, the international attention that surrounded Hungarian ‘new textiles’ was still significant in the movement’s heyday, as it can be detected in many solo and group exhibitions of artists of the field, 9 but today it needs to be rediscovered by the international audience.

As a prominent and regular participant in textile/fabric art exhibitions and a key shaper of the events, Margit Szilvitzky is among the first artists whose work should be analysed and reassessed. She participated among other prominent and, at the time, internationally recognised artists in the groundbreaking group exhibition ‘Textile Wall Hangings ‘68’ (Textil falikép ‘68) at the Ernst Museum, Budapest, a grassroots initiative by the professional circles of textile art. The radicalism of the exhibition seems less apparent today, but its intention

to break away from the standard events (which dictated that tapestries were to be produced, based on cartoons designed by painters, at professional, state-operated weaving workshops) of the 1950s and 1960s is still striking. 10 This show also paved the way for establishing the institutional system with the participation of professional and administrative parties, which eventually provided the textile movement with an organisational framework in Szombathely. In 1970, the Wall and Spatial Textiles Biennials 11 were launched, preceding the International Tapestry Triennials in Łódź. The Savaria Museum, Szombathely also established its own textile art collection, similarly to the Central Museum of Textiles in Łódź. With the support of the Ministry of Light Industry, the Biennial of Industrial Textile Art followed in 1973. Beginning in 1976, 11 the International Biennial of Miniature Textile Art (Nemzetközi Miniatűrtextil Biennálé) started, parallel with spatial textile art – or perhaps as its counterpoint, creating a particular genre that resonated with the variations of pop art, conceptual art and mail art. It was also under the auspices of the Szombathely centre that the Textile Art Workshop in Velem started its operations, as part of the symposium movement, which allowed room for experimental tendencies and a generation of younger artists.

This golden age of ‘new textiles’ offered neo-avant garde art an unprecedented degree of freedom, with the heightened attention of the professional media. Thanks to it, its history is relatively well-documented. Its institutional system was built with state support that also served to keep the movement’s activities under official control. This unusual freedom can partly be explained by the centralised Hungarian cultural life, i.e. the geographical distance between Szombathely/Velem and the Hungarian capital. Although there was a lot of ‘back

and forth’ with official bodies, 12 this situation was correlated with a ‘more permissive’ official stance that relegated textile art back to the domain of the applied arts.

As László Beke puts it, this official stance regarded ‘non-figurativity insufficient in itself as a genre, but functional for the purposes of ornamentation’. 13 This also applied to textile art, which was considered as an ornamental practice, rather than an autonomous medium. The most defining factor, however, was the traditionally peripheral position of textile art considered to be ‘decorative’ – in the hierarchy of genres of arts, to which the dominant presence of ‘harmless’ women was a contributing element. 14 Eventually, the ‘new textiles’ community was atomised, which, in contrast to initial experiments in formulating an integrative view, 15 resulted in the segregation of genres in the longer run. 16 Within the movement, there was always a simultaneous presence of autonomous tendencies open in the direction of the fine arts (exploring the possibilities of fibre art, spatial textile art, installation genres and textile objects), along with endeavours drawing on concepts of more traditional and conventional approaches to textiles. The expectation that this new attention on textile art would clarify the role of applied artists and modern designers in socialist industry also figured into the equation. However, in the absence of the much-coveted architectural commissions, the opportunities for demonstrating the mural possibilities of textile art were minimal. To refer to Péter Fitz’s retrospective overview, 17 the end of the golden age of textile art – also accelerated by state interventions in an effort to curtail radical tendencies 18 – can in part be explained by a result of the new textile art leaving behind its roots in applied arts and entering into the exhibition space. This phenomenon was represented by such (post) conceptual group exhibitions organised in the spirit of ‘thought-textiles‘ or ‘anti-textiles’ 19 as ‘Textiles after Textiles’ (‘Textil a textil után’, 1979) or ‘Textiles without Textiles’ (‘Textil textil nélkül’, 1979). The rediscovery of painting – as it was enhanced by the Hungarian ‘New Sensibility’ exhibitions (a series of group shows related to the international phenomenon of ‘new painting’ in the 1980s) in the wake of Postmodernism entering Central Europe – in the 1980s also contributed to the experimental, heroic period of the neo-avant garde coming to an end, 20 and ultimately brought a revival and renewal of the tapestry genre with it. 21 The other path, which offered a solution for the internal problems of textile art, yielded its own movement in the late eighties: the discovery of Läufer (fabric used for absorbing excess dye in textile printing) offered an opportunity to move in the direction of painting. With the ‘heroic age’ coming to an end, this shift marked a turning point also for Szilvitzky after her long journey in applied and autonomous fabric art, eventually turning her to painting in the second half of the eighties. A noteworthy characteristic of Szilvitzky’s work is ready-made but always natural fabric created by mass production, a tendency that led her to her trademark material, basic white canvas/linen in the mid-seventies. Even when she started experimenting with fabric as an autonomous material, she used waste from the fashion studio she was working in at the time, using natural, but ready-made linen, hemp, burlap and jute that she dyed by hand with natural materials.

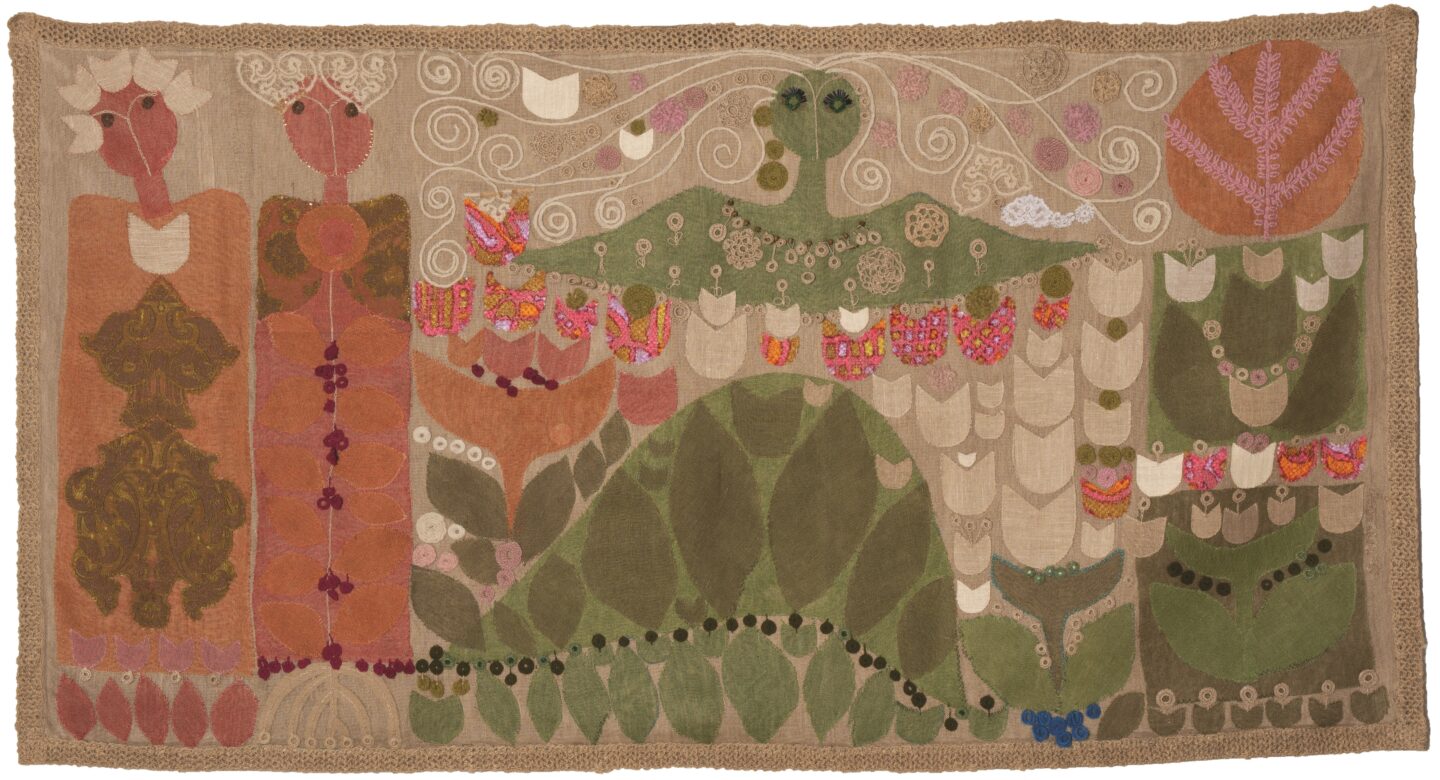

Margit Szilvitzky: Spring, 1967-68 dyed and natural linen, applique, embroidered, sewn mixed media, 96 × 180 cm, Photo by Miklós Sulyok Courtesy of Savaria Megyei Hatókörű Városi Múzeum – Szombathelyi Képtár / Savaria Municipal County Museum – Kunsthalle Szombathely, inv. no. I.2019.3.1.

It is best demonstrated by her piece Spring (Tavasz), which became a successful exhibit at the ‘Textile Wall Hangings ‘68’ show. Like many other works in this time, it is an appliqué textile-collage, 22 bearing undeniable kinship to assemblage. These aspects reflected an intention of a unified spatial arrangement at her 1970 solo exhibition at the Institute for Cultural Relations (Kulturális Kapcsolatok Intézete) in Budapest. Natural fabrics, arranged into a single image plane along with various other materials (lace, velvet, beads, etc.), dominated these works, with the pervasive use of organic/natural motifs in different stages of reduction. The nature of these works is essentially a product of an ‘abstracting’ outlook derived from analysing the symbol systems – rooted in the examination of nature elements – of traditional clothing and folk object culture, on the one hand, and of the concurrent exploration of Hungarian turn-of-the-century art with its roots in folk art, on the other, simultaneously accompanied by increasingly ‘rustic’ and reduced works. The material also revealed the shift towards spatial textile art, mainly prompted by Planes in Space (Síkok a térben). During this period, Szilvitzky was predisposed to employing the tools of direct references – or ‘quotes’ from the history of material culture 23 – and appropriation, which connected areas of history, folk art and history of culture, as well as the cultic and liturgical object culture (Cloak – Palást, 1969; Dalmatic – Dalmatika, 1970). Her solo exhibition, held in the medieval Solomon-tower of Visegrád in 1972, offered a condensed summary of her research into the history of clothing and the findings of structural anthropology. The artist created the ‘abstracted’, ‘performative’ scene of a rite, where human-like figures appeared – referred to by Zsuzsa Szenes as ‘dolmens’. 24 These are distant relatives to Abakanowicz’s figures, organised in a ritual-like fashion, concentrating on the plastic possibilities of fabric. The main element of the displayed group of objects is Hommage à…/Altar (Hommage à…/ Oltár): a ‘nature altar’ relief 25 – incorporating an element of cork wrapped in fabric that would become the artist’s central motif in the following years, bringing to mind the practice of the Supports/Surfaces group.

Embroidery played a part in the initial period of Szilvitzky’s engagement of ‘soft’ and ‘amorphous’ forms, accompanied by ‘organic’,

biological shapes. On closer inspection, they seem to approximate the characteristic visual language of essentialist women’s art (see Living

Form – Élő forma, 1971; Unfolding – Kibontakozás, 1969), a phenomenon appearing in the Western scene, when Szilvitzky and her generation began their careers. This wave of ‘women’s art’ articulated its identity by reaffirming biological sex and validating the female bodily experience. Textiles – and the knowledge that any material can be transformed into fibre, and thus function as a textile – along with the act of hanging the artwork, were seen as meaningful elements in this context. ‘Masculine’ minimalism was diffused through the introduction of ‘feminine’ qualities in the works of such artists as Eva Hesse. Hannah Wilke and Judy Chicago should also be mentioned here; both captured women’s experience by representing female genitalia as their explicit ‘feminine motif’. 26 Magdalena Abakanowicz’s early Abakans (Abakany), the Swiss-Hungarian Klára Kuchta’s sisal works from the first half of the seventies, or Ilona Keserü’s Tangle (Gubanc) works can be included in this phenomenon. At the same time, thanks to their geopolitical conditions, these works remain far removed from the currents of feminism; the artist – as well as her whole generation – did not bring them into connection with women’s experiences; instead, she linked them to nature. Szilvitzky writes, ‘the forerunners of my motifs include the halved pomegranate, watermelon and even pumpkin.’ 27 Just like Ilona Keserü, 28 or even Magdalena Abakanowicz – who insisted on her art being gender neutral, 29 and whom Szilvitzky considered a major influence (and with whom she met in Warsaw in 1980 along with Zofia Butrymowicz and Jolanta Owidzka), Szilvitzky denied being engaged in women’s art, even expressing her mistrust in it. This approach resonates with her generation’s, and even younger artists’ ‘latent, or even better to say, implicit feminist’ 30 attitude towards the matter. It can be interpreted in this way: since socialism had offered a fake opportunity for social emancipation by creating the image of the working woman – whose duties as a mother and housekeeper, in reality, remained, in addition to working fulltime – the general public mistrust in feminism was enhanced after 1989. 31 However, most female artists of these generations seem to accept the presence of a ‘female viewpoint’ in their work. Szilvitzky shared the same opinion, according to the video interview feminist artist Orshi Drozdik conducted with her in 2010. 32 This mistrust can be traced back to their intention to avoid any connection with the classical, academic ‘female’ genres, thus they chose universal, abstract visuality. It was the way to avoid double or even triple discrimination among their male colleagues even in avant-garde circles. 33 However, since Rozsika Parker’s defining book 34, we know that, in a patriarchal setting, the kind of invisible work performed by women (weaving, sewing, embroidery, knitting, etc.) has a crucial role in how the concept of womanhood is constructed. These primary tools of creating and articulating women’s various narratives play a key role in women asserting their viewpoint and telling ‘herstory’ as can be detected in the archetypal stories of Penelope, Arachne and Philomela. 35 For Szilvitzky and her generation (represented by Zsuzsa Szenes and Marianne Szabó) finding their path to embroidery appears to have been of crucial importance in articulating their own, autonomous personalities as artists, even though it soon became an activity that they detested, as it was old-fashioned (even if being engaged with such an activity was a conscious decision on their side) 36 and synonymous with the ‘female’ applied arts that they aimed to change radically. 37 As Szilvitzky recounts in her book, 38 her first embroidered images, like Twins (Ikrek),picturing her own daughters from 1965, were created in the private sphere – within the spaces of the family and the children’s room. It appears that it was this invisible ‘womanly’ work and creative power that enabled the artists to use their own voice without being explicitly subversive in form and content. Such reproductive work sequestered itself in private life and intimate spaces (the ‘children’s corner’, as mentioned in Géza Perneczky’s article on the new generation of textile artists emerging in the late 1960s). 39 This notion cannot be regarded separately from the discovery of Art Nouveau in the sixties, a certain Neo-Jugendstil – a phenomenon that was detested initially both by avant-garde circles and the official art scene, as it was considered a reflection of bourgeois aesthetics and a visual world traditionally considered typically ‘feminine’.

After her folk-art-rooted tulip motifs and the fairytale-telling spirit of her Spring, Szilvitzky established the quadrilobate motif – rooted in folk ornamentation and medieval architecture (Flower Wings – Virágszárnyak, 1969, Flower Nest – Virágfészek, 1968). The resulting structures can be set in parallel with the swirling jumble of yarn in Ilona Keserü’s Tangle pictures, as well as her canvas-curving works. 40 A parallel can be drawn between Szilvitzky’s studies in folk art – centred on traditional folk costumes, as well as folk object culture and symbolism –, and tendencies emerging in the fine arts which were observable in the works of certain ‘Iparterv’ artists 41 like Ilona Keserü, or István Nádler and Imre Bak.

The gradual exploration of the sculptural possibilities of textiles – in pieces like Flexible Forms (Hajlékony formák), a prize winning spatial textile presented at the Biennial in Szombathely in 1974 – added to her turn to folding paper, and later, fabric. She became engaged with the square, the Malevichian ‘pure form’ 42 (in addition to other basic geometric shapes, always connected to the square or the cube). The square – reflecting on the traditions of Cubism, Suprematism, Russian Constructivism, 43 De Stijl, concretism and post-war tendencies touched by structuralism – along with the emblematic grid pattern of modernism, as referred to by Rosalind Krauss 44 were dominant forms in Szilvitzky’s 1976 exhibition in Kőszeg. The network of the vertical weft and horizontal warp threads – as a unique feature of woven textile, and, thus, of the canvas used as a support for the painting – is the most essential, ‘infinite’ grid system

fathomable. This material simultaneously becomes the support and the object of representation in Szilvitzky’s art – similarly to that of Agnes Martin not long before. Szilvitzky’s discovery of the square – as it is even remembered in her emblematic process artwork of tracing paper, Finding the Square I– III (A négyzet megtalálása I– III, 1975) determined the course of her later career. 45 She rapidly made her way from the mentality of the Black Square on a White Background to White on White with its meditative atmosphere. When Szilvitzky says that she was inspired by ‘the economy of Dutch puritanism and the intangible mysticism of Mark Rothko’s handling of paint’, 46 she draws attention to the fact that her interest in modernism has dual roots. That is to say, mystical monochromatic gesture painting came together with Mondrian’s Neo-Plasticism, forming a bridge to the square-shape-based, geometrically ordered tradition of concretist and serial art. In turn, following in the footsteps of Theo van Doesburg, this led to the art of Ad Reinhardt, Max Bill and Josef Albers.

Her memorable square-based textile sculptures, like Open Square (Nyitott négyzet) and Square Space (Térnégyzet) (both 1979), attempt to

capture a representational method using the tools of textile art. These works, as meta-models of the central perspective representing reality – and by that token, of Alberti’s ‘window’ – leave the form simultaneously open and closed. At the same time, they stress the inseparability of spatial thinking from temporality, as the planes suspended behind one another in Square Space emphasise the temporal dimension of moving forward in space. In this respect, too, we can see a kinship to Dóra Maurer’s film entitled Timing (Időmérés, 1973–1980), where the gesture of folding is used as a signifier of temporal relationships. 47 The mini textile work entitled Interior (Enteriőr) – which exists in several versions – was created with a method similar to the one used in Square Space, but without sewing. The artist was invited to present this work at the 1979 International Exhibition of Miniature Textiles in London, after which it traveled around the globe, eventually being reproduced in one of the best known handbooks on textile art at the time, alongside pieces by such artists as Margot Rolf, Anne Wilson, Harry Boom, Emilia Bohdziewicz, and Corrie de Boer. 48

Margit Szilvitzky: Interior, 1977, constructed, folded linen, ribbon, 20 × 20 × 20 cm Photo by Dávid Tóth Courtesy of acb Gallery and the artist’s heirs

The 1976 show in Kőszeg signified an important milestone in her journey toward expanding the experimental and fine art-related conceptualisation of textiles. It was at this show that 100x100 Squares (100x100-as négyzetek) and Evidence I-II (Evidenciák I-II) were first presented. The squares created (from one-square-metre pieces of canvas) through triangular folding and with the use of a sewing machine are two-dimensional, but they model and accentuate the spatial quality created with textile surfaces while also carry tactile value. The structural, textural and surface aspect effects of folding and slashing, and the origami-like possibilities of shaping through folding, are explored in Evidence I-II, a work that borrows the characteristic motifs of concrete art. The artist’s serial works and process art pieces drew her systematising and system-seeking attention not only to examining the sculptural potential of fabric and the possibilities of turning a two-dimensional plane into three-dimensional space but also to the exploration of light and shadow in relation to one another. 49 Also, the problem of transposing graphic gestures to textile made its appearance in Kőszeg. The possibilities of the spatial and visual elements’ arrangement into a ‘situation’ 50 was explored in the textile installation Adjustment (Igazodás), which consisted of a sequentially shaped strip of linen, ‘cascading’ down the ladder’s rungs onto the floor. The strip of fabric ‘bore’ the graphic element of the line, which was also present in the piece Line (Vonalív), presented at the Szombathely Biennial in 1976. Just like these two spatial textile works, the individual pieces of the group of works Szilvitzky created for the 1977 exhibition in Helsinki can also be regarded as ‘demonstrational objects’ of visual regularities. 51 One of these works presented in Helsinki was her first Modulation (Moduláció) built on the ‘harmonica motif’, which can be viewed either as series of modules multiplying hexagonal formations bounded by ironed edges or as elements of shaping space in the spirit of Moholy-Nagy.

Her search for a systematic method for creating variations through folding, along with the constant analysis of – and experimentation with

– materials, was closely linked with the work conducted within the framework of Art Studies, a course taught by Szilvitzky at the Academy of Applied Arts, which was based on Bauhaus practice and had the development of students’ visual thinking as its objective. The methods and material-based experiments that she applied in her course – in addition to their connection to the practice of such artists as Anni Albers 52 – were in large part inspired by the paper studies of Josef Albers. 53 This connection’s influence could be felt in the maximal economy of folded forms with respect to the material, along with the equality of visual elements, the artist’s recognition of the form-creating potential of absence, and her openness to the unexpected. The exploration and utilisation of edges and angles (see: Marginalia series, 1978), their use as lines, the juxtaposed gestures of crumpling, tearing and slashing, as well as the transparency and layering brought into play by folding, were all initially realised through Szilvitzky’s experiments with paper. She then applied her paper-based observations to even more shapeable fabrics, as well as to collages, drawings, spatial installations – and then, in the late eighties, to appliquéd and painted canvases. The commonality of the canvas as raw material (and the collective experience of folding clothes and sheets) rendered the questions raised by the works ‘experienceable’, connecting Szilvitzky’s pieces with the expansion of art into the realm of everyday life. 54

Ironing and folding dominated Open Processes I–II–III (Nyitott folyamatok I–II–III) too, Szilvitzky’s key work exhibited at the 1978

Biennial of Szombathely, which summarises her artistic method and attitude regarding the analysis of space with the means of the fabric.

‘I continued with the method of ironed edges and superimposed, folded layers, with the only difference being colour: […] I chose a livelier yellow canvas. I wanted to show the outlines of the ironed edges, so I unfolded one of the pieces and laid it out on the floor. In the second part, I wanted to demonstrate the appropriation of space […]. I compressed the third piece of the group along the ironed creases into minimal size; I closed the space.’ 55 This work became so significant that her retrospective exhibition in 2002, which put together and highlighted the connections between the artist’s drawings and textile works, got its title after this piece as a metaphor for Szilvitzky’s working method and creative process.

Installation view, Margit Szilvitzky’s exhibition, Amos Anderson Museum, Helsinki, 1977 On the wall: Restructuring, 1977 (in the collection of Szent István Király Múzeum / King St. Stephen Museum, Székesfehérvár) On the floor: Floor objects, 1977 Photo by László Lelkes Courtesy of the artist’s heirs

Besides the square and other basic geometric shapes, paper, and subsequently the fabric ribbon (inescapably calling to mind Max Bill’s

sculptures of the Möbius strip) became a central element in her visual language as it was formulating throughout the seventies. This can be

detected in the first version of Restructuring (Átrendeződés),which was also displayed in Helsinki in 1977. This work is a representation of the relationship between the textile ribbon, the two-dimensional plane and three-dimensional space, of the duality of closedness and continuation, spatial segmentation and repetition, as well as, once again, the possibilities of the line – a calligraphic element – as a graphic entity transposed to textiles. In the spatial textile work entitled Open Square, the viewer’s gaze is guided by a line-like strip drawn through a window into the depths: it becomes a tool of communication, while also serving to elicit optical and perceptional experiences, and – in addition to the vertical and horizontal axes – also lending the textile sculpture the dynamism of the diagonal. Using ribbons and their gestural possibilities led the artist back to experimenting with chromatic qualities, and thus eventually to painting: her Ribbon (Strip), Story (Szalagtörténet), presented at the Hungarian Cultural Centre in Helsinki in 1986 was the first step in this direction. The other significant group of works paving the way towards painting are the collages entitled Qualities of Ivy Green, Scarlet Red and Black (Méregzöld, Skarlátvörös és Fekete minőségek). These are material and colour samples that refer to the ribbon motif and the elongated hexagonal bases of the ‘spatial geometrical modules’ from 1977.

The returning cycles of motifs used by the artist in her drawings, paper works and paintings from the late eighties onwards ultimately aided the artist in developing her own private mythology, made up of basic geometric shapes, ribbon segments and fragments of cultural

memory. Touched by the overwhelming influence of Postmodernism, accompanied by the quest for new ways in ‘new textiles’, Szilvitzky’s

work shifted towards more settled genres of fine art. However, her approach to other genres – especially drawing and painting – never fully broke away from the methods she developed when working with fabric and as a result of her activities in teaching. Textiles served as a starting point and a framework of her activities even after the late 1980s.

Bibliography

- Aknai, Katalin, ‘“Állandóan visszajárok a múltamba”. Keserü Ilona életművének vizsgálata a hatvanas évek perspektívájából’ (doctoral thesis, ELTE BTK Filozófiatudományi Doktori Iskola, 2014)

- Albers, Josef, ‘Werklicher Formunterricht’, Bauhaus Zeitschrift für Gestaltung 2, 2/3 (1928), 3–7

- Amidon, Catherine S., ‘Different Voices with Common Threads: Polish Fiber Art Today’, The Polish Review, 43, no. 2 (1998), 195–206

- András, Edit, Kulturális átöltözés – Művészet a szocializmus romjain (Budapest: Argumentum Kiadó, 2009)

- Attalai, Gábor, ‘About the Circumstances’, in Eleven textil 1968–1978– 1988. Válogatás a modern magyar textilművészeti alkotásokból / Living Textile 1968–1978–1988: A Selection from Contemporary Hungarian Works of Textile Art, exh. cat., ed. by Ibolya Herczeg (Budapest: Műcsarnok – Savaria Múzeum, 1988), pp. 85–105

- Attalai, Gábor, ‘Morfondírozások a hetvenes évek textilművészetéről (avagy) egy félben maradt történet’, Magyar Iparművészet,

4 (1994), 38 - Attalai, Gábor, Objektek, szituációk és ellenpontok lágy anyagokkal, exh. cat. (Budapest: Műcsarnok/Kunsthalle, 1981)

- Balázs, Kata, ed., SZILVITZKY Margit: A négyzet megtalálása. Művek 1968–1988 / Finding the Square. Works 1968–1988 (Budapest: ResearchLab, 2021).

- Beke, László, ‘Kísérleti textil’, Savaria – A Vas megyei Múzeumok Értesítője 1975–76, 9–10 (1980), 321–324

- Beke, László, ‘Szilvitzky Margit művészete’, Magyar Építőművészet, 6 (1970), 54–55.

- Beke, László, ‘The Stories and Concepts of Margit Szilvitzky’, in Nyitott folyamatok II. Válogatott munkák / Open Processes. Selected Works 1972–2002, exh. cat. (Szombathely: Kunsthalle Szombathely, 2002), pp. 9–12

- Beke, László, ‘Tűrni, tiltani, támogatni – A hetvenes évek avantgárdja’, in A második nyilvánosság. XX. századi magyar művészet, ed. by Hans Knoll (Budapest: Enciklopédia, 2002), pp. 228–247

- Buzás, Árpád, ‘Nem felejteni kell, hanem… Iparművészek kiállításpolitikája Magyarországon 1966 és 1973 között, avagy intelmek a fiatal generációnak’, Magyar Iparművészet, 3 (2001), 83–93

- Cebula, Anna, ‘A Szombathelyi Képtár textilgyűjteményének története’, in A gödöllői textil 100 éve. Tanulmányok a 20. századi Magyar textilművészet történetéhez, ed. by Cecília Őriné Nagy (Gödöllő: Gödöllői Városi Múzeum, 2009), pp. 97–101

- Constantine, Mildred, Jack Lenor Larsen, Wall Hangings (New York: Museum of Modern Art, 1969)

- Daly Goggin, Maureen, ‘Stitching a Life in “Pen and Steele and Silken Inke”: Elizabeth Parker’s circa 1830 Sampler’, in Women and the Material Culture of Needlework and Textiles 1750–1950, ed. by Maureen Daly Goggin and Beth Fowkes Tobin (London and New

York: Routledge, 2016), pp. 31–48 - Eberhardt-Cotton, Giselle, ‘The Lausanne International Tapestry Biennials [1962–1995]: The Pivotal Role of a Swiss City in the “New

Tapestry” Movement in Eastern Europe after World War II’, in Textiles and Politics: Textile Society of America 13th Biennial Symposium Proceedings (Washington DC: Textile Society of America. Textiles&Politics, 2012) <https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/cgi

/viewcontent.cgi?article=1669&context=tsaconf> [accessed 30 October 2021] - Fer, Briony, ‘Black Mountain College Exercises’, in Anni Albers, ed. Ann Coxon, Briony Fer, Maria Müller-Schareck (London: Tate Modern, 2018), pp. 64–67

- Fitz, Péter, ‘Nyugtalan természet vagyok. Beszélgetés Szilvitzky Margittal 85. születésnapja okán’, Új Művészet, 2– 3 (2016), 20–23

- Fitz Péter, ‘Textilművészet 1974–1984 között’, in Szombathelyi Textilbiennálék 1970–2000, ed. by Éva Sütő (Szombathely: Szombathelyi Képtár, 2002), pp. 27–43

- Fitz, Péter, ‘The Adventures of Hungarian Textile Art (1968–1986)’, in Eleven textil 1968–1978–1988. Válogatás a modern magyar

textilművészeti alkotásokból / Living Textile 1968–1978–1988: A Selection from Contemporary Hungarian Works of Textile Art,

exh. cat., ed. by Ibolya Herczeg (Budapest: Műcsarnok – Savaria Múzeum, 1988), pp. 7–65 - Forgács, Éva, ‘Együttműködni a képpel’, Artmagazin, 6 (2008), 78–82

- Forgács, Éva, Hungarian Art: Confrontation and Revival in the Modern Movement (Los Angeles: Doppel House Press, 2016)

- Frank, János, Az eleven textil. Új magyar textilművészet, térbeliség, tárgyak (Budapest: Corvina, 1980)

- Gál, Csaba, ‘A vörös fonál mentén az 1960-as és 70-es évek textilművészetében’, in 1971 – Párhuzamos különidők, ed. by Dóra Hegyi et al. (Budapest: BTM Kiscelli Múzeum, 2019), pp. 92–101

- Gyetvai, Agnes, ed., Szilvitzky Margit. Válogatás három évtized munkáiból / A Selection from Three Decades’ Works, exh. cat. (Budapest: Műcsarnok / Kunsthalle, 1988)

- Gyetvai, Ágnes, ‘The Mantle of Ophelia’s Night’, in Szilvitzky Margit. Válogatás három évtized munkáiból / A Selection from Three Decades’ Works, exh. cat., ed. by Ágnes Gyetvai (Budapest: Műcsarnok / Kunsthalle, 1988), pp. 30–34

- Herczeg, Ibolya, ed., Eleven textil 1968–1978–1988. Válogatás a modern magyar textilművészeti alkotásokból / Living Textile 1968–1978–1988: A Selection from Contemporary Hungarian Works of Textile Art, exh. cat. (Budapest: Műcsarnok – Savaria Múzeum, 1988)

- Horowitz, Frederick A., Brenda Danilowitz, Josef Albers: To Open Eyes (London: Phaidon, 2009)

- Husz, Mária, A magyar neoavantgárd textilművészet (Budapest: Dialóg Campus, 2001)

- Inglot, Joanna, The Figurative Sculpture of Magdalena Abakanowicz: Bodies, Environments, and Myths (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2004)

- Kígyós, Erzsébet, ‘Amíg mozog a kezem, addig rajzolni még lehet. Beszélgetés Szilvitzky Margittal’, Artmagazin, 4 (2017), 32–39

- Körner, Éva, Avantgárd izmusokkal és izmusok nélkül. Válogatott cikkek és tanulmányok, ed. by Katalin Aknai, Sándor Hornyik (Budapest: MTA-MKI, 2005)

- Krauss, Rosalind, ‘The Grid’, October, 9 (1979), 50–64

- Larsen, Jack Lenor, Mildred Constantine, The Art Fabric: Mainstream (New York: Kodansha International Ltd., 1985)

- Mezei, Ottó, Szilvitzky Margit (Budapest: Corvina, 1982)

- Mihály, Mária, ‘Az aranykor 1968–1978’, in Szombathelyi Textilbiennálék 1970–2000, ed. by Éva Sütő (Szombathely: Szombathelyi Képtár, 2002), pp. 10–26

- Nyitott folyamatok II. Válogatott munkák / Open Processes. Selected Works 1972–2002, exh. cat. (Szombathely: Kunsthalle Szombathely, 2002)

- Parker, Rozsika, The Subversive Stitch: Embroidery and the Making of the Feminine (London: Woman’s Press Ltd., 1984)

- Perneczky, Géza, ‘A fekete négyzettől a pszeudo-kockáig. Kísérlet a kelet-európai avantgarde tipológiájának megalapozására’, Magyar Műhely, 16, no. 56/57 (1978), 27–45

- Perneczky, Géza, ‘Művészeti búvópatakok’, Valóság, 6 (1969), 76–80

- Scheuing, Ruth, ‘The Unravelling of History: Penelope and Other Stories’, in Material Matters: The Art and Culture of Contemporary Textiles, ed. by Ingrid Bachmann, Ruth Scheuing (Toronto: YYZ Books, 1998), pp. 201–213

- Sütő, Éva, Szombathelyi Textilbiennálék 1970–2000 (Szombathely: Szombathelyi Képtár, 2002)

- Szenes, Zsuzsa, ‘Szilvitzky Margit kiállítása’, Ipari Művészet, 3 (1972), 23

- Tatai, Erzsébet, A lehetetlen megkísértése. Alkotó nők – Válogatott esszék, tanulmányok magyar művészetről (Budapest: Új Művészet KiadóMTA BTK, 2019)

- Tatai, Erzsébet, Neokonceptuális művészet Magyarországon a kilencvenes években (Budapest: Praesens, 2005)

Video interview with the artist

- Radikális Magyar művészet 1975 és 1980 között, Szilvitzky Margit (Radical Hungarian Art Between 1975 and 1980, Margit Szilvitzky), directed by Orshi Drozdik, 2013

The artist’s own writings

- Szilvitzky, Margit, A farmertől az ünneplőig. Öltözködés és kreativitás (Budapest: Corvina, 1982)

- Szilvitzky, Margit, A látás élménye. Művészeti tanulmányok az Iparművészeti Főiskolán (Budapest: Nemzeti Tankkönyvkiadó, 1995)

- Szilvitzky, Margit, Folyamatos jelen. Művek, műfajok, kommentárok (Budapest: Balassi, 2007)

- Szilvitzky, Margit, Öltözködés, divat, művészet I– III (Budapest, Corvina, 1971), republished as Az öltözködés rövid története (Budapest: Corvina, 1974)

- The present text is an abbreviated and altered version of the essay ‘SZILVITZKY Margit: Művek / Works 1968–1988’ by the same author,

in SZILVITZKY Margit: A négyzet megtalálása. Művek 1968–1988 /

Finding the Square. Works 1968–1988, ed. by Kata Balázs (Budapest:

ResearchLab, 2021). The translation is based on Zsófia Rudnay’s work,

revised by Eszter Greskovics in its final form. ↩︎ - Her books, especially on the history of clothing and fashion include Öltözködés, divat, művészet I– III [Clothing, Fashion, Art I– III] (Budapest: Corvina, 1971); republished in 1974 under the new title Az öltözködés rövid története [A Brief History of Clothing]. See also: A farmertől az ünneplőig. Öltözködés és kreativitás [From Jeans to Formal Wear: Clothing and Creativity] (Budapest: Corvina, 1982). She published A látás élménye. Művészeti tanulmányok az Iparművészeti Főiskolán [The Experience of Vision: Visual Education at the Hungarian Academy of Applied Arts] (Budapest: Nemzeti Tankkönyvkiadó, 1995) about her teaching practice. ↩︎

- The critique was published in the Finnish periodical Helsingin Sanomat on 27 November 1977. Quoted in: Margit Szilvitzky, Folyamatos jelen. Művek, műfajok, kommentárok (Budapest: Balassi, 2007), p. 73. ↩︎

- A connection can be drawn between this approach and Noémi Ferenczy’s (1890–1957) approach, which went against the concept that considered tapestry art as a means for reproducing paintings and created the basis for modern Hungarian tapestry. ↩︎

- Catherine S. Amidon, ‘Different Voices with Common Threads: Polish Fiber Art Today’, The Polish Review 43, no. 2 (1998), 195–206. ↩︎

- Mildred Constantine, Jack Lenor Larsen, Wall Hangings (New York: Museum of Modern Art, 1969). ↩︎

- The artist remembers it in an interview, see: Radikális Magyar művészet 1975 és 1980 között, Szilvitzky Margit (Radical Hungarian Art Between 1975 and 1980, Margit Szilvitzky), directed by Orshi Drozdik, 2013. ↩︎

- Árpád Buzás, ‘Nem felejteni kell, hanem… Iparművészek kiállításpolitikája

Magyarországon 1966 és 1973 között, avagy intelmek a fiatal generációnak’, Magyar Iparművészet, 3 (2001), 83–93 (p. 87). See also: Giselle Eberhardt-Cotton, ‘The Lausanne International Tapestry Biennials [1962–1995]: The Pivotal Role of a Swiss City in the “New Tapestry” Movement in Eastern Europe after World War II’, in Textiles and Politics: Textile Society of America 13th Biennial Symposium Proceedings (Washington DC: Textile Society of America. Textiles&Politics, 2012) <https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/cgi /viewcontent.cgi?article=1669&context=tsaconf> [accessed 30 October 2021]. ↩︎ - Árpád Buzás, ‘Nem felejteni kell, hanem… Iparművészek kiállításpolitikája Magyarországon 1966 és 1973 között, avagy intelmek a fiatal generációnak’, Magyar Iparművészet, 3 (2001), 83–93 (p. 87). See also: Giselle Eberhardt-Cotton, ‘The Lausanne International Tapestry Biennials [1962–1995]: The Pivotal Role of a Swiss City in the “New Tapestry” Movement in Eastern Europe after World War II’, in Textiles and Politics: Textile Society of America 13th Biennial Symposium Proceedings (Washington DC: Textile Society of America. Textiles&Politics, 2012) <https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1669&context=tsaconf> [accessed 30 October 2021]. ↩︎

- The latest, fundamental research-based study on the official tapestry art that preceded – and existed in parallel with – the ‘textile revolution’ draws attention to practices of ‘new textiles’ and ‘state’ commissioned tapestry projects created with funds from the two-thousandths budget (which declared that two-thousandths of public investments and constructions had to be spent on art) or financed directly by the state, with detailed focus on the tapestry design work of visual artists. Csaba Gál, ‘A vörös fonál mentén az 1960-as és 70-es évek textilművészetében’, in 1971 – Párhuzamos különidők, ed. by Dóra Hegyi et al. (Budapest: BTM Kiscelli Múzeum, 2019), pp. 92–101. ↩︎

- For bureaucratic reasons, the first Szombathely International Biennial of Miniature Textile Art could only be held in 1976. A Hungarian edition was organised in 1975, which became an international event a year later. There is still a debate among former participants about whether the idea of organising the Miniature Textile Art Biennial in Szombathely preceded the one in London (starting in 1975). ↩︎

- Gábor Attalai, ‘About the Circumstances’, in Eleven textil 1968–1978–1988. Válogatás a modern magyar textilművészeti alkotásokból / Living Textile 1968–1978–1988: A Selection from Contemporary Hungarian Works of Textile Art, exh.cat., ed. by Ibolya Herczeg (Budapest: Műcsarnok – Savaria Múzeum, 1988), pp. 85–105. See also: Mária Mihály, ‘Az aranykor 1968–1978’, in Szombathelyi Textilbiennálék 1970–2000, ed. by Éva Sütő (Szombathely: Szombathelyi Képtár, 2002), pp. 10–26. ↩︎

- László Beke, ‘Tűrni, tiltani, támogatni – A hetvenes évek avantgárdja’, in A második nyilvánosság. XX. századi magyar művészet, ed. by Hans Knoll (Budapest: Enciklopédia, 2002), pp. 228–247 (p. 384). Géza Perneczky also makes reference to this in his writing ‘A fekete négyzettől a pszeudo-kockáig. Kísérlet a kelet-európai avantgarde tipológiájának megalapozására’, Magyar Műhely, 16, no. 56/57 (1978), 27–45. ↩︎

- Multiple critiques at the time touched on this point of consideration. László Beke drew attention to the insustainability of the negative view

of the textile industry and textile art as ‘feminine’ genres. ‘Kísérleti textil’, Savaria – A Vas megyei Múzeumok Értesítője 1975–76, 9–10 (1980), 321–324. In Géza Perneczky’s essay ‘Művészeti búvópatakok’, Valóság, 6 (1969), 76–80, the fact that all textile artists in the latesixties were women is articulated as the central consideration of his analysis. ↩︎ - In addition to critiques and analytical texts following various points of considerations towards synthesis, similar intentions were shown by such initiatives as the exhibition ‘Thoughts on Light Materials’ (‘Gondolatok lágy anyagokra’, 1979) at the Young Artists’ Club (‘Fiatal Művészek Klubja’) and ‘Objects, Situations and Counterpoints with Soft Materials’ (‘Objektek, szituációk és ellenpontok lágy anyagokkal’), curated by the ‘theoretician’ of ‘new textile’ Gábor Attalai, and held at Műcsarnok/Kunsthalle Budapest in 1981. ↩︎

- This point is stressed in Éva Forgács, ‘Együttműködni a képpel’, Artmagazin, 6 (2008), 78–82, and in Gábor Attalai, ‘Morfondírozások a hetvenes évek textilművészetéről (avagy) egy félben maradt történet’, Magyar Iparművészet, 4 (1994), 38. ↩︎

- Péter Fitz, ‘The Adventures of Hungarian Textile Art (1968–1986)’, in Eleven textil 1968–1978–1988 / Living Textile 1968–1978–1988, ed. by Ibolya Herczeg, pp. 7–65. ↩︎

- Éva Forgács, ‘Együttműködni a képpel’, and Mária Husz, A magyar neoavantgárd textilművészet ↩︎

- László Beke, ‘Kísérleti textil’, p. 324 ↩︎

- Fitz Péter, ‘Textilművészet 1974–1984 között’, in Szombathelyi Textilbiennálék 1970–2000, ed. by Éva Sütő, pp. 27–43 (p. 42). ↩︎

- Szilvitzky also had similar thoughts on the matter, as she expressed on

several platforms: ‘I no longer like to talk much about textile art, because there has been too much talk of the “golden age of textile art”. What is meant by that is the decade whose pinnacle was probably signified by the biennial entitled +-Gobelin in 1980. In effect, it was the Gobelin artists who benefited most from the whole process. Prior to that, it was the painters who designed the tapestries. However, during this period, textile artists wove their own Gobelin works, mobilising all their creativity and renewing the technique (e.g. dense warping, weaving yarns/ threads of various thickness into the tapestry, combining the widest range of materials, such as paper – or even film strips – with wool, and so on). By the 1980s, Gobelin hit a slightly more autonomous tone.’ Péter Fitz, ‘Nyugtalan természet vagyok. Beszélgetés Szilvitzky Margittal 85. születésnapja okán’, Új Művészet, 2–3 (2016), 20–23 (p. 20) ↩︎ - This method calls to mind the methods used by the makers of the traditional Hungarian peasant coat referred to as a szűr ↩︎

- László Beke, ‘Szilvitzky Margit művészete’, Magyar Építőművészet, 6 (1970), 54–55. ↩︎

- Zsuzsa Szenes, ‘Szilvitzky Margit kiállítása’, Ipari Művészet, 3 (1972), 23. ↩︎

- Ottó Mezei, Szilvitzky Margit (Budapest: Corvina, 1982), p. 17. ↩︎

- Miriam Schapiro’s ‘craft’ activities and the colourful approach of the Pattern and Decoration movement, which openly went against rational geometrisation, not only opened new vistas for craft and needlework but also paved the way for new freedom in the diverse use of textiles and its creative, ‘high art’ potential. While these voices spoke from the position of the hobby artist outside the grand narrative of art history, after bringing the women’s perspective to the fore, they also facilitated the self-identity formation of other minorities who were searching for their own voice in the postcolonial context. ↩︎

- János Frank, Az eleven textil. Új magyar textilművészet, térbeliség, tárgyak (Budapest: Corvina, 1980), p. 113. ↩︎

- Katalin Aknai, ‘“Állandóan visszajárok a múltamba”. Keserü Ilona életművének vizsgálata a hatvanas évek perspektívájából’ (doctoral thesis, ELTE BTK Filozófiatudományi DoktoriIskola, 2014) ↩︎

- She even broke away from weaving, assuming that the medium of her activity confined the interpretations of her work, see Joanna Inglot, The Figurative

Sculpture of Magdalena Abakanowicz: Bodies, Environments, and Myths (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2004), pp. 67–68. ↩︎ - Erzsébet Tatai, A lehetetlen megkísértése. Alkotó nők – Válogatott esszék, tanulmányok magyar művészetről (Budapest: Új Művészet Kiadó-MTA BTK, 2019). ↩︎

- Edit András, Kulturális átöltözés – Művészet a szocializmus romjain (Budapest: Argumentum Kiadó, 2009); Erzsébet Tatai, Neokonceptuális művészet Magyarországon a kilencvenes években (Budapest: Praesens, 2005). ↩︎

- Orshi Drozdik, Radikális magyar művészet 1975 és 1980 között, Szilvitzky Margit ↩︎

- Katalin Aknai, ‘“Állandóan visszajárok a múltamba”’ ↩︎

- Rozsika Parker, The Subversive Stitch: Embroidery and the Making of the Feminine (London: Woman’s Press Ltd., 1984). A reworked edition was published in 1996. ↩︎

- Maureen Daly Goggin, ‘Stitching a Life in “Pen and Steele and Silken Inke”: Elizabeth Parker’s circa 1830 Sampler’, in Women and the Material Culture of Needlework and Textiles 1750–1950, ed. by Maureen Daly Goggin and Beth Fowkes Tobin (London and New York: Routledge, 2016), pp. 31–48. See also Ruth Scheuing, ‘The Unravelling of History: Penelope and Other Stories’, in Material Matters: The Art and Culture of Contemporary Textiles, ed. by Ingrid Bachmann, Ruth Scheuing (Toronto: YYZ Books, 1998), pp. 201–213. Erzsébet Tatai drew attention to Scheuing’s work in Neokonceptuális művészet Magyarországon a kilencvenes években, p. 119. ↩︎

- János Frank, Az eleven textil, p. 113. ↩︎

- Orshi Drozdik, Radikális magyar művészet 1975 és 1980 között, Szilvitzky Margit ↩︎

- Margit Szilvitzky, Folyamatos jelen. Művek, műfajok, kommentárok, p. 20. ↩︎

- Géza Perneczky, ‘Művészeti búvópatakok’. ↩︎

- Éva Forgács,‘Együttműködni a képpel’. ↩︎

- ‘Iparterv I’ and ‘Iparterv II’ were two exhibitions organised by Péter Sinkovits in 1968 and in 1969. The shows, organised in the building of the Iparterv State Architectural Office in Budapest, were fundamental manifestations of the neo-avant-garde in Hungary. The participating artists included Imre Bak, András Baranyay, Miklós Erdély, Krisztián Frey, Tamás Hencze, György Jovánovics, Ilona Keserü, Gyula Konkoly, László Lakner, János Major, László Méhes, Sándor Molnár, István Nádler, Ludmil Siskov, Tamás Szentjóby and Endre Tót. ↩︎

- The Malevichian connection is further highlighted by Szilvitzky’s view of

the square – after discovering this basic geometric form for herself – as an ‘icon’, thereby bringing to mind the manner in which Malevich’s Black Square was displayed at the ‘0.1’ exhibition in Saint Petersburg in 1915. See Péter Fitz, ‘Nyugtalan természet vagyok’, p. 22. ↩︎ - The discovery of Rozanova’s and Popova’s work in the eighties, thanks to art historian Éva Körner, influenced Szilvitzky’s approach even considering that art extends through all genres, from drawing to ceramics, textile, bookmaking, fashion design. Her attachment to the Russian artists is commemorated in the Läufer piece, My Friend, Olga Rozanova (Barátnőm, Olga Rozanova, 1987). ↩︎

- Rosalind Krauss,‘The Grid’, October, 9 (1979), 50–64. ↩︎

- The language of forms used in her paper collage entitled With Paper on Paper (Papírral papíron, 1978) and, later, her art book Suprematist Sample Book (Szuprematista mintakönyv, 1997) suggests a close kinship to Suprematism. Her work Play Area (Játéktér) uses the tools of appropriation insofar as it employs motifs from the works of Malevich and Theo van Doesburg. Éva Forgács, Hungarian Art: Confrontation and Revival in the Modern Movement (Los Angeles: Doppel House Press, 2016), p. 262. ↩︎

- Erzsébet Kígyós, ‘Amíg mozog a kezem, addig rajzolni még lehet. Beszélgetés Szilvitzky Margittal’, Artmagazin, 4 (2017), 32–39 (p. 38) ↩︎

- László Beke, ‘The Stories and Concepts of Margit Szilvitzky’, in Nyitott folyamatok II. Válogatott munkák / Open Processes. Selected Works 1972–2002, exh. cat. (Szombathely: Kunsthalle Szombathely, 2002), pp. 9–12. ↩︎

- Jack Lenor Larsen, Mildred Constantine, The Art Fabric: Mainstream (New York: Kodansha International Ltd., 1985), p. 134. ↩︎

- By way of her serial works, we see a connection with such artists as Péter Türk and András Mengyán. Her use of folding as a basic artistic tool links her to such fellow contemporaries as Simon Hantaï and his pliage technique, or from the smaller local circles of textile art, Aranka Hübner,by way of her pleated textile reliefs. Furthermore, her methodical geometric shaping of the material and her technique of folding connects Szilvitzky’s works to Tibor Gáyor’s systematic mathematical approach or some works by Dóra Maurer and Vera Molná r. It is through her graphic works experimenting with the wrinkling and folding of the printing plate and her Hidden Structures (Rejtett struktúrák) frottages that Dóra Maurer’s art comes into close affinity with Szilvitzky’s drawings experimenting with graphic representations of light-and-shadow relationships within paper and textile structures. Vera Molnár, a Hungarian artists living in France, is known as the pioneer of computer art but also designed woven fabrics. In her serial works combining structured order and randomness,

the square as the basis of methodical research was just as defining as in the works of Szilvitzky, who shared similar artistic roots. The use of fabric’s sculptural qualities connects Szilvitzky’s approach with that of György Jovánovics, while the square/cube as a defining element, her method of crumpling and playing on the deceitful qualities of the artwork’s surface creates a less evident connection to Gyula Pauer’s pseudo concept. ↩︎ - Gábor Attalai, Objektek, szituációk és ellenpontok lágy anyagokkal, exh. cat. (Budapest: Műcsarnok / Kunsthalle, 1981), p. 16 ↩︎

- Ágnes Gyetvai, ‘The Mantle of Ophelia’s Night’, in Szilvitzky Margit. Válogatás három évtized munkáiból / A Selection from Three Decades’ Works, exh. cat., ed. by Ágnes Gyetvai (Budapest: Műcsarnok / Kunsthalle, 1988), pp. 30–34 (p. 34). ↩︎

- One of the most prominent figures in Bauhaus textiles, Anni Albers, in her teaching practice at Black Mountain College, placed the exploration of texture in the centre of her focus in order to ‘regain sensitivity towards textile surfaces’. As a unique counterpoint and complement to her husband Josef Albers’ educational method, rearranging found materials into rectangular forms – grids – and transforming natural materials through simple movements or gestures were constant elements in her teaching practice, which

placed emphasis on the sense of touch and the significance of formal repetition. This approach can be traced back in Szilvitzky’s work, too. See: Briony Fer, ‘Black Mountain College Exercises’, in Anni Albers, ed. by Ann Coxon, Briony Fer, Maria Müller-Schareck (London: Tate Modern, 2018), pp. 64–67. ↩︎ - Josef Albers, ‘Werklicher Formunterricht’, Bauhaus Zeitschrift für Gestaltung 2 (Dessau), 2/3 (1928), 3–7. See also: Frederick A. Horowitz and Brenda Danilowitz, Josef Albers: To Open Eyes (London: Phaidon, 2009). ↩︎

- Éva Körner, exhibition opening speech, Institute for Cultural Relations, Budapest, 1977. (Published in Szilvitzky Margit, ed. by Ágnes Gyetvai,

pp. 8–9; Éva Körner, Avantgárd izmusokkal és izmusok nélkül. Válogatott cikkek és tanulmányok, ed. by Katalin Aknai, Sándor Hornyik (Budapest: MTA-MKI, 2005), pp. 104–105; Margit Szilvitzky, Folyamatos jelen, pp. 24–25.) ↩︎ - Margit Szilvitzky, Folyamatos jelen, p. 81. ↩︎

Kata Balázs

Kata Balázs graduated in Art History and Hungarian Literature and Linguistics at ELTE Budapest. She held various scholarships at the Jagiellonian University and at the University of Florence. She completed the doctoral program of ELTE and is working on obtaining her PhD. Apart from periods spent at Ludwig Museum and working as a junior researcher grantee at the Hungarian Academy of Sciences, she taught at various schools and universities like the University of Film and Theatre or the University in Eger. She has been working at acb ResearchLab since 2020. In her work, a special focus is placed on the art of the 1980s, photography and performance art and since recently, textile/fibre art.