Title

Elżbieta Nadel’s Images from Home 18 Sketches from Nature, Lvov, 1942*

https://www.doi.org/10.48285/8kaewzmo3p

https://miejsce.asp.waw.pl/en/english-elzbieta-nadels-images-from-home-18-sketches-from-nature-lvov-1942/

Abstract

This article is a preliminary attempt to analyze Elżbieta Nadel’s drawing collection “Obrazki domowe. 18 szkiców z natury, Lwów 1942” [Images from Home: 18 Sketches from Nature, Lvov 1942]. The author combines methodologies from art history, history and literary criticism. Focusing on the materiality and intermediality of the work, she analyzes “Obrazki domowe” as a historical source and personal document of the Holocaust, and finally as a feminine trace of these events.

Adopting (auto)biographical optics, the article analyzes the visual narrative emerging from “Obrazki domowe” as the self-portrait of a young girl who uses humor and irony to represent herself and her historical moment. She turns her home into a fortress sealed off from hunger, violence, and mass death.

Elżbieta Nadel, born June 1, 1920 in Lvov, died August 8, 1944 in Israel as Elisheva Landau. In Israel, she worked as an artist, illustrating books and periodicals. She studied graphic arts at the Fine Arts Institute in Lvov, where she met Kazimierz Moździerz (born 1918, Lvov; died: 1997, Bytom). Moździerz, who studied painting, helped Nadel and her mother flee Lvov for Warsaw.

DOI

Elżbieta Nadel’s Images from Home: 18 Sketches from Nature, Lvov, 19421

Some years ago, when I first encountered Elżbieta Nadel’s drawing series Obrazki domowe. 18 szkiców z natury [Images from Home: 18 Sketches from Nature], I recognized them at once as an invaluable artifact of the Holocaust. I also knew that they would pose no small challenge to Holocaust scholars and art historians. Due to the collection’s irrefutable artistic merit, it stands up to the standard criteria and methods of art history. Its value, however, transcends Nadel’s formal fluency, stylistics, and the relation between her subject and form. The status of Obrazki domowe is elevated when we see the drawings as a record of their moment—as biographical testimony, and as a feminine trace of the Holocaust.2 The collection is also a material trace, and the portfolio’s good condition invites one to think of its physicality as well as its resilience.

With the notable exception of photography, visual testimonies of the Holocaust (often taking the form of modest drawings) are rarely afforded the same historical value as wartime diaries or the personal notes of people in hiding.3 Their status sets them apart from written sources and material artifacts. Yet this should not detract from their capacity to bear witness to the past, even if they do so in a nondiscursive manner.

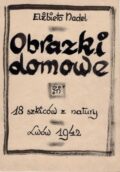

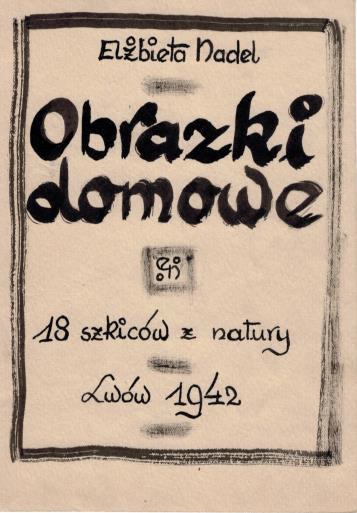

Elżbieta Nadel, Title Card: Elżbieta Nadel “Obrazki domowe. 18 szkiców z natury”, Lwów 1942 [Images from Home. 18 Sketches from Nature, Lvov 1942], approximately.

20.5 x 14 cm, ink/bristol paper, 1942, Muzeum Historii Żydów Polskich POLIN [POLIN Museum of the History of Polish Jews].

As one such testimony of ghetto existence, Nadel’s Obrazki domowe should be heeded as a historical source. As the expression of a specific state of consciousness that the artist wished to convey to the world, it is also a personal document and work of art. I want to acknowledge the methodological challenges posed by this Holocaust document/artwork. To undertake a close analysis of Obrazki domowe, it is necessary to distinguish between its artistic merits and underlying historical context without neglecting its materiality, intermediality, or the biographical perspective of its female author. Only by synthesizing these many aspects can we arrive at a fair reading of the work.

*

Elżbieta Nadel was born on June 1 of 1920 in Lvov (then Polish Lwów). Her parents were doctors: her mother, Regina Nadel (née Reichenstein), was born in Lvov on December 15 of 1891, and died in Israel. Regina received her degree in 1917 and was a practicing dermatologist and specialist in venereal diseases. This was also the profession of her husband, Aron Nadel, born in Ternopil (then Tarnopol) on September 12 1890 (d. 1944). He received his degree in 1915,4 and by 1924, the couple had opened a medical practice in a building at number 7 Halicki Square, which doubled as the family’s home before the war.5

The Nadels had two children: Elżbieta and Jerzy (b. 1926). Elżbieta studied graphic arts at the Fine Arts Institute in Lvov, where she met Kazimierz Moździerz (b. 1918, Lvov; d. 1997, Bytom). Moździerz, who studied painting, would later help Elżbieta and her mother flee Lvov for Warsaw. In an account for Yad Vashem, Nadel laconically describes her experience of the war: “After the Great Action in Lvov in August, 1942 (when my 16-year old brother died), my parents and I left for Warsaw, where I lived under “Aryan papers” (father died) until the Polish uprising. We managed to get to Warsaw thanks to Kazimierz Moździerz, who escorted us there at the risk of his life and helped us find an apartment. We stayed in Warsaw until the Polish uprising and its defeat in 1944, when we fled to Pruszków, living out what remained of the war in this little town outside of Warsaw. There, we worked as nurses in a hospital for the wounded.6 In Warsaw, we supported ourselves by making macramé. After the Russians took over the city, and after searching for a family member to no avail, we moved to Prague and eventually onward to Israel in 1948.”7

In Israel, Elżbieta Nadel married Naftali Landau and adopted his surname, changing her first name to Elisheva. She worked as an artist, illustrating books and periodicals (including Israel’s most prominent daily Haaretz). She never returned to Poland after the war and passed away on August 8, 1994.

On Obrazki domowe [Images from Home]

The portfolio known as Images from Home consists of a title card and 18 drawings in black ink that are numbered and signed. The dimensions of each card are roughly 20.5 x 14 cm.8 The cards are cut from stiff, high-quality Bristol paper with a subtle cream hue. The portfolio includes one unnumbered drawing: Plan mieszkania / skala 1:66 [Apartment Floorplan / Scale 1:66].9 The folder holding the drawings is cut sparingly from black paperboard and equipped with narrow inserts. Its side and top wings were folded by hand.10 On the front and backsides of the case and on its righthand wing are inscriptions and drawings painted in gouache. The green title Obrazki / domowe / 18 szkiców [Images / from Home / 18 Sketches] is followed by lettering in yellow paint that reads: “Elżbieta Nadel” on the top row and “Lvov 1942” just below. The words are accompanied by colorful renderings of a chamber pot and broom. These details may have been added later, as we can deduce from the placement of the artist’s name squeezed in above the title. Below, on the righthand wing, is the word “July” hand-painted in green. On the folder’s backside, a Star of David appears in brown paint, consisting of two (roughly) equilateral triangles of varying size. A square has been drawn into the star’s middle section,11 framing the artist’s decorative monogram: e. / n.

Elżbieta Nadel, “1. nasze mieszkanie…” [our apartment…], 20.5 × 14 cm, ink/bristol paper, 1942, Muzeum Historii Żydów Polskich POLIN [POLIN Museum of the History of Polish Jews].

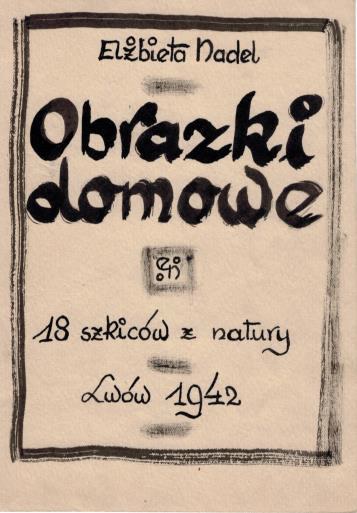

Elżbieta Nadel, “2. miłe…” [sweet…] 20.5 × 14 cm, ink/bristol paper, 1942, Muzeum Historii Żydów Polskich POLIN [POLIN Museum of the History of Polish Jews].

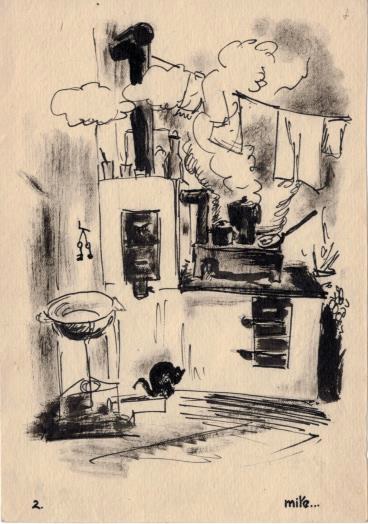

Elżbieta Nadel, “3. obszerne /pięć minut dla zdrowia/…” [roomy /five minutes for good health/…], 20.5 × 14 cm, ink/bristol paper, 1942, Muzeum Historii Żydów Polskich POLIN [POLIN Museum of the History of Polish Jews].

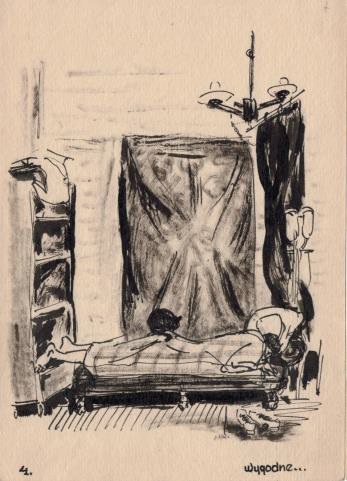

Elżbieta Nadel, “4. wygodne…” [comfortable…], 20.5 × 14 cm, ink/bristol, paper, 1942, Muzeum Historii Żydów Polskich POLIN [POLIN Museum of the History of Polish Jews].

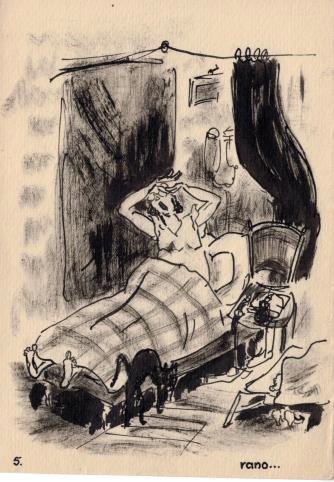

Elżbieta Nadel, “5. rano…” [morning…], 20.5 × 14 cm, ink/bristol paper, 1942, Muzeum Historii Żydów Polskich POLIN [POLIN Museum of the History of Polish Jews].

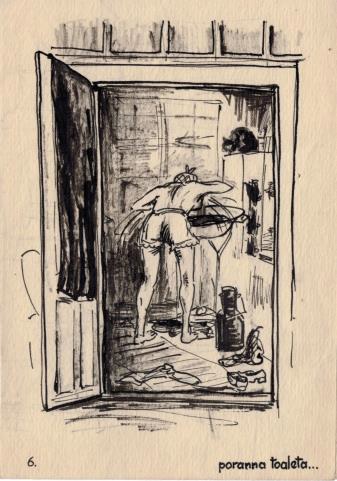

Elżbieta Nadel, “6. poranna toaleta…” [morning toilette…], 20.5 × 14 cm, ink/bristol paper, 1942, Muzeum Historii Żydów Polskich POLIN [POLIN Museum of the History of Polish Jews].

The portfolio’s graphic handiwork is in itself an indicator of the artist’s robust skill set, as the meticulous lettering attests: the letters are hand-drawn, playfully spaced, and scribed in stylized cursive.12 The compact font size imbues the work with intimacy. We find similar writing on the title page, which reiterates the information on the folder and adds one new detail making it 18 szkiców z natury [18 Sketches from Nature]. The title card, like the drawings that follow, is rendered in black ink with a fine paint brush and calligraphy pen. The title letters seem to have been first outlined by pen and then filled in with saturated black ink (through which the pen strokes are often still visible).13 In lieu of the cover illustration (the chamber pot and broom), we see a square framing the initials e. / n.14 All this is enclosed within a simple border likely drawn with a calligraphy pen: the upper line is vivid, but the other lines are faded, as if the ink was running low.

The drawings are picturesque and imbued with levity.15 Nadel used the ink’s full spectrum of shades, alternating between strong, subtle, and faded tones and skillfully manipulating contrasting accents of darkness and light. The compositions capture the home on a range of scales, depicting the building’s full exterior while also attending to details and niches indoors. All drawings share a vertical orientation and are numbered from 1–18 (the number appears in the lower-left corner). The lower-right corners are occupied by title/descriptions that, together, suggest a narrative:

-

nasze mieszkanie… [our apartment…]

-

miłe… [sweet…]

-

obszerne /pięć minut dla zdrowia/… [roomy/five minutes for good health/…]

-

wygodne… [comfortable…]

-

rano… [morning…]

-

poranna toaleta… [morning toilette…]

-

wieczorem… [in the evening…]

-

wodociąg… [water main…]

-

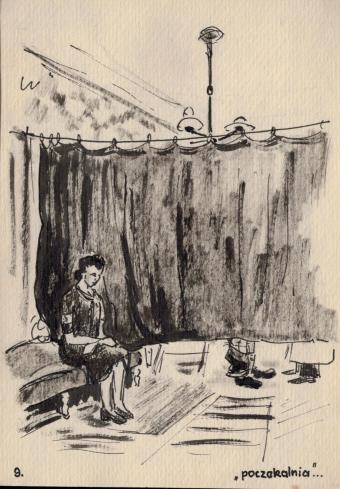

“poczekalnia”… [“waiting room”…]

-

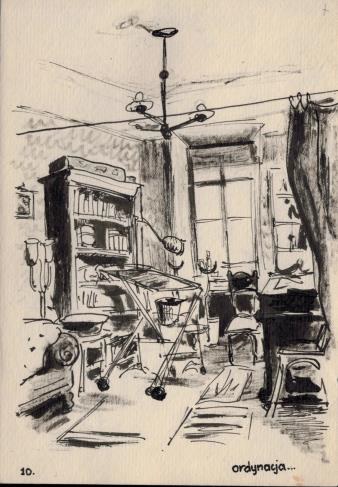

ordynacja… [treatment…]

-

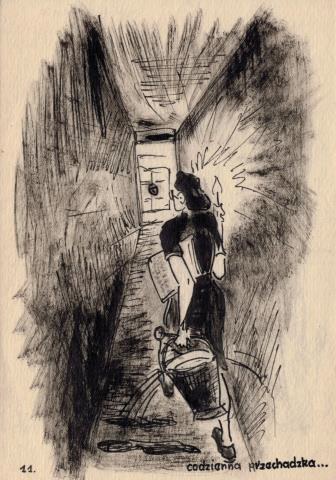

codzienna przechadzka… [daily stroll…]

-

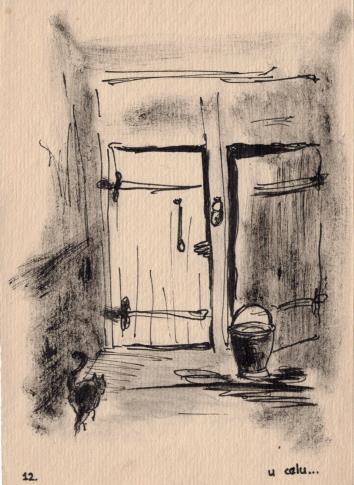

u celu… [destination…]

-

przy stole… [at the table…]

-

główne porządki… [housecleaning…]

-

wielkie pranie… [laundry day…]

-

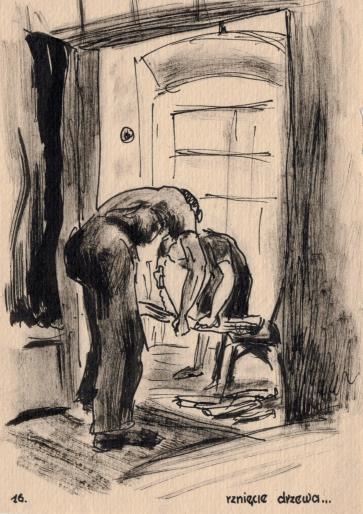

rznięcie drzewa… [chopping wood…]

-

o zmroku…. [at dusk…]

-

po pracy… [after work…]

Let us now take a close look at the drawings one by one:

-

nasze mieszkanie… [our apartment…] is a panoramic view of a stairwell and balustrade. The view opens onto an alcove with double doors. On the righthand door hangs a white rectangular placard reading: DR. NADEL. The drawings that follow align into a narrative that progresses along two tracks, moving through the place and space of the home, but also through time (from morning to evening):

-

miłe… [sweet…] We stand by the front doors, in a space that functions as kitchen, washroom and foyer. Close to the door, a round basin with handles sits on a metal base. Two keys hang from a nail on the wall. To the left of the doorway, next to the kitchen, is a tiled stove with a ventilation pipe leading outdoors. Chopped wood lies on the floor, and the stove is cluttered with pots and a pan. Steam rises from the pots, and laundry hangs from a line overhead. A black cat huddles at the stove’s base.

-

obszerne /pięć minut dla zdrowia/…[roomy/five minutes for good health…] Again, we find ourselves in the galley kitchen. We see the familiar entryway, washing area and stove. To our left, a table has been set with dishes, and a bucket sits on the floor. At the center of the space, we discern the figure of a young woman fervently exercising. She wears a light shirt, lace-trim bloomers, and shoes. The drawing catches her as she bends to the ground, left hand craning toward her right foot. The vigorous motions of her torso and arms (a move called a “windmill” in gymnastics) send the whole kitchen into a tailspin: bowls and mugs tumble from the stovetop, keys swing pendulum-style from a nail in the wall, plates fly off the table and water spills from a mug. The cat scurries off in a fright.

-

wygodnie… [comfortable…] We see a bed, or rather a divan not quite long enough to accommodate a person. Bare feet jut out from under a skimpy checkered blanket to rest on the lower shelf of a wardrobe. A person (the artist?) sleeps on her belly. On the slight bulge that indicates her buttocks is the cat—sleeping comfortably. The divan, arranged here in the corridor/waiting room, will return in later scenes (drawings 9 and 10) but will be tucked against the wall.

-

rano… [morning…] The first minutes upon waking. The drawing shows the same bed and same person from a new perspective: a young woman stretches. She wears glasses and a shirt, and her hair hangs loose to her shoulders. At the foot of the bed stands the cat, its back arched and legs sticking straight. It’s also time for the cat to rise and shine.

-

poranna toaleta… [morning toilette…] We spy her through the doorframe: the same young woman, now half-dressed and performing her morning ablutions (her whole body visible, glimpsed from behind). Barefoot, she leans over a bowl set into the wash basin. Nearby is a water jug. Shoes and clothing lay scattered on the floor. From the stovetop, she is keenly observed by the cat.

-

wieczorem… [in the evening…] A view from the common room onto several unmade beds in the foyer. Beds are arranged in the waiting room, family room, and the threshold between them (the double doors hang open). In the waiting room, by a curtain, sleeps the story’s protagonist. On the drawing’s left side, we glimpse part of another folding bed, and on the right, a headboard, pillow, and someone preoccupied with a newspaper (we see only the first letters of the masthead GAZ, hinting at “gazeta,” the Polish word for newspaper).

-

wodociąg… [water main…] On the stairwell (see drawing 1), in the arcade foyer, is a sink in the shape of a clamshell. Water streams from the sink to the floor. Its audience is the cat.

-

“poczekalnia”… [“waiting room”…] An area slightly removed from the entryway. Against the wall is the familiar divan, now functioning as a seat for a woman in a summer dress. A Star of David armband is visible on her right arm.16 A makeshift curtain strung on a cord partitions this part of the room (also cutting off the top of the divan). The curtain does not provide full coverage, for it reaches neither the ceiling nor floor. The distinct black shape of the curtain is the composition’s guiding motif. Behind it stand two men (we see only their legs): a patient on the left, pants dropped to his feet, and the doctor (also male) wearing black pants, loafers and a white smock.

-

ordynacja… [treatment…] A view from the waiting room into the office. The curtain previously used as a partition is drawn to the right side. In the depths of the foyer is a tall window, and to the left, by the wall, we see part of the divan and a bowl next to a water pitcher. Above these objects, a painting hangs from a nail. There is also a suitcase resting on a tall bookshelf. An elevated bed (perhaps a medical bed?) is arranged nearby. A chair and desk occupy the far corner of the room.

-

codzienna przechadzka… [daily stroll…] Down the long, narrow, dark and dingy corridor to the toilets17 comes a vigorous young woman with short hair and glasses. Her figure is seen from behind, but her face is subtly turned toward the viewer. She carries a bucket in her left hand, and a newspaper is folded under one arm. Her right hand carries a candle, lighting the way.

-

u celu… [destination…] Wooden doors assembled from planks lead to two toilet stalls. The door on the left is brighter, perhaps cleaner. Someone holds it shut from the inside. The right-hand door is barely ajar, and a bucket waits on the floor just outside. Down the left wall, tail erect, flits the cat.

-

przy stole… [at the table…] A square table under a tablecloth, around which sit four people: a young man (on the left, his figure in full view); a woman (seen from behind); another woman (to her right); and a man in the background. The woman on the right sits with her head bowed, temple cradled in her left hand. Arranged on the table are bottles, plates. To the left, seated on the broad base of a bed, the cat attends the family meal.

-

główne porządki… [housecleaning…] The windows are wide open, and bedding is laid out to dry on the sill. Inside, a young woman stands amidst the furniture, wearing slippers and a black, knee-length dress. She holds a broom in her hands and stands perfectly still, adrift in thought. The cat hides under a stool.

-

wielkie pranie… [laundry day…] The same room: in the corner, between a lamp, wall and stove, hangs a laundry line. Stockings are draped over a chair. A teacup and teapot sit on a mat-covered table at whose edge sits the cat.

-

rznięcie drzewa… [chopping wood…] This drawing takes place in the window alcove. A woman and young man use a hand saw to cut a log propped between chairs. To their right, on the floor, fresh wood chips accumulate on the floor.

-

o zmroku… [at dusk…] The windows are again thrown open, revealing a potted flower on the sill. A young woman, seen from behind and wearing a dark dress, gazes out the window. To the right of the window is an armchair with checkered upholstery, where the cat sleeps curled in a ball.

-

po pracy… [after work…] In the room, by a table (which is in fact a folded down flap from the bookcase), sits the same woman bent over her work. An inkwell, ink bottle, pen and sheet of paper are spread out on the table. To the left looms a tall bookcase. A paraffin lamp and suitcase rest on its top. The cat sits on the floor, by the table, head turned toward the woman and tail resting flat on the ground.

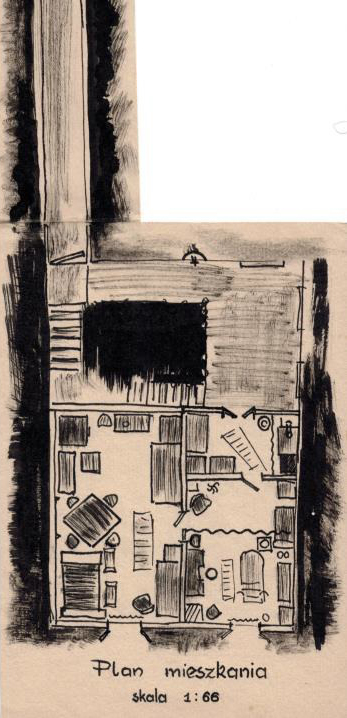

The drawings are accompanied by Plan mieszkania / skala 1:66 [Apartment Floorplan / Scale 1:66]: a detailed reconstruction of the layout of the furniture, stove and other items (like a coatrack in the waiting room). This guide allows the viewer to situate themselves within the space of the home—an area of about 30 square meters. The effect is that the viewer can visualize the interior and even physically orient themselves within it.

Elżbieta Nadel, “plan mieszkania / skala 1:66” [apartment floorplan, scale 1:66], ink/bristol paper, 39.7 × 14.1, 1942, Muzeum Historii Żydów Polskich POLIN [POLIN Museum of the History of Polish Jews].

Perspectives on Obrazki domowe [Images from Home]

Art works from the Holocaust “function as records, reports, traces, and often testimonies.”18 All these terms seem valid in the case of Nadel’s drawings. This complicates the task of analyzing their many valences. To do so, I found it necessary to describe each card in detail. This became an entry point into the work of analyzing the portfolio as a historical source and personal document. Ultimately this process revealed intimate meanings and impressions embedded in the moment of July 1942.

Time and Place

Lvov, 1942. The month is July. On September 1, 1939, after Germany’s aggressions toward Poland and in accordance with the Molotov-Ribbentrop Pact, Lvov was annexed by the Soviet Union. Under Soviet occupation, social and economic conditions changed dramatically for all of Lvov’s inhabitants, regardless of faith. The city’s upper echelons—tradespeople, factory owners, bureaucrats, and independent professionals—took a particularly drastic blow. Stripped of their property and discharged from work, they were subject to political pressures and eventually threatened with arrest, exile, or death. On June 22, 1941, the Third Reich invaded the Soviet Union. By June 30 the Germans had taken Lvov. Yet even before the German army had reached the city limits, violent assaults broke out, targeting Jews. There were raids, beatings and even killings. In the first three days of July, a pogrom took place during which about 4,000 Jews were killed.19 In the weeks that followed, “ad hoc actions and assaults”20 swept the city, culminating tragically in what is remembered as the “Petliura Days,” beginning on July 25, during which approximately 2,000 people perished. According to Filip Friedman, “[t]he Jewish people of Lvov, seized with panic, refrained from even leaving their homes. Most of them hid in their apartments or in hideouts in basements or attics.”21 How the Nadel family survived these days is unknown to us. The effects of these dramatic events on the psyche of Lvov’s Jewish population were enormous.

Approximately 150 thousand Jews were killed in German-occupied Lvov.22 Officially, the Lvov Ghetto was established on November 6 of 1941 in a neighborhood behind the embankment of the Lvov-Ternopil railway line. Its bordering streets were Warszawska, Zamarstynowska, Zniesienie and a segment of Pełtewna.23 However, Lvov’s Jewish population did not move en masse into this district until September of the following year. Most likely, the Nadels were among those who stayed outside the designated Ghetto. In a survey distributed by the Lvov Department of Health in March 9 of 1942, Aron Nadel listed his address as Farbenstrasse 20/5 (formerly Boimów Street), which is located in the Old Town. In other words, presumably, the Nadels had indeed moved, but not far from their former residence.24

During these resettlements households were only allowed to retain “essential” items. It was impossible, for instance, to transport all the equipment needed for a medical office. Conditions in the Ghetto were exceedingly difficult. There was a housing shortage and many buildings had no electricity, plumbing, or running water.25 Starvation was rampant.26 Exhausted from work, harassment, and the strain of living in constant fear, the people of the Lvov Ghetto were given no respite. In isolation, the Jewish people of Lvov could not indulge in even illusory feelings of safety (ghetto diaries from other cities speak of a similar state of mind). The roundups were relentless: in December of 1941, unemployed people were targeted. Women, children, and the elderly were assembled together and murdered. The subsequent and perversely named “minor deportations” took place in March, April, June, and July of 1942. August 10 of that year marked the beginning of the “Great Action,” during which approximately 50,000 Jews were killed, including Elżbieta’s younger brother Jerzy.27 The Lvov Ghetto was liquidated in 1943, thus finalizing the genocide of Lvov’s Jews. By that time Elżbieta and her parents had fled the city.

Elżbieta Nadel, “7. wieczorem…” [in the evening…], 20.5 × 14 cm, ink/bristol paper, 1942, Muzeum Historii Żydów Polskich POLIN [POLIN Museum of the History of Polish Jews].

Elżbieta Nadel, “8. wodociąg…” [water main…], 20.5 × 14 cm, ink/bristol paper, 1942, Muzeum Historii Żydów Polskich POLIN [POLIN Museum

of the History of Polish Jews].

Elżbieta Nadel, “9. “poczekalnia”…” [“waiting room”…], 20.5 × 14 cm, ink/bristol paper, 1942, Muzeum Historii Żydów Polskich POLIN [POLIN Museum of the History of Polish Jews].

Elżbieta Nadel, “10. ordynacja…” [treatment…], 20.5 × 14 cm, ink/bristol paper, 1942, Muzeum Historii Żydów Polskich POLIN [POLIN Museum of the History of Polish Jews].

Elżbieta Nadel, “11. codzienna przechadzka…” [daily stroll…], 20.5 × 14 cm, ink/bristol paper, 1942, Muzeum Historii Żydów Polskich POLIN [POLIN Museum of the History of Polish Jews].

Elżbieta Nadel, “12. u celu…” [destination…], 20.5 × 14 cm, ink/bristol paper, 1942, Muzeum Historii Żydów Polskich POLIN [POLIN Museum of the History of Polish Jews].

Even compared to the abysmal conditions in the ghettos of Warsaw, Cracow and Lodz, the situation facing Lvov’s Jews was disastrous from the occupation’s first days.28 On May 30, 1942, Abraham Lewin, a teacher from Warsaw and member of the Oyneg Shabbos group, wrote the following: “Today, a lawyer from Lvov spent two hours telling us (a group of social activists) the story of the Lvov Gehenna and all of Eastern Galicia. He told us things so hideous and macabre that words cannot grasp what transpired there. In Lvov alone, around 30,000 martyrs perished. The mass murders were organized into three primary stages. (…) The details of these events are so terrible that I cannot bring myself to jot them down between journal notes. (…) I count these two hours among the most tragic of my life.”29

Self-Portrait; Portrait of the Self

The conditions facing Lvov’s Jewish population under German occupation provide a historical framework defining the time and place in which Elżbieta Nadel made her journal. Images from Home are a portrait of Elżbieta herself, for she is the protagonist of nearly all the drawings. This makes the work an autobiographical document for which the artist, narrator, and “autobiographical subject” share a unified identity.30 The phrase “literature of personal document,”31 culled from Polish literary criticism, may aptly describe this mode. This genre includes forms such as “journals, collected letters, diaries and other forms of personal notetaking not necessarily written with the aim of making a product of artistic merit.”32 And yet, for Obrazki domowe, which straddles the worlds of images and words, a second term may be more appropriate: that of “women’s personal narratives” understood in the term’s broadest scope as encompassing diverse analytical perspectives.33

The artist, narrator and autobiographical subject of Obrazki domowe is a woman now well known to us, for she wrote herself into her images several times over: on the cover, title card, and in the recurring monogram. Identifying herself as a woman, she integrates her gender and corporeality into the work.34 It is also fair to infer that the young woman appearing in most of the scenes—wearing glasses and a dress, hair cut fashionably short—is Elżbieta Nadel, although our only material proof is the white door placard reading DR. NADEL. A second hint lies in the collection’s title, which nods to the intimacy of these sketches drawn from Home and from Nature.

Having agreed on the cohesive biographical pact of Images from Home, we can better attend to the personal narrative unfolding from drawing to drawing. While the descriptions assigned to each scene are impersonal, the visual narrative seems to follow Elżbieta’s point of view. I will therefore refer to her as the story’s heroine and identify its other protagonists relative to her, by consulting her biography. Placing Elżbieta at the story’s center, we can identify others in supporting roles (the cat), as well as an ensemble of minor characters (her parents and brother).

In Obrazki domowe, Elżbieta’s life is confined to the family sphere and the transient temporality of a home whose isolation from the outside world is nearly absolute. The only allusions to the world beyond the home are the patients (like the woman in the waiting room with a Star of David armband). While this home is the product of displacement (the suitcases in drawings 13 and 18 hint at the family’s recent move), it is nonetheless an oasis of refuge. It is not by chance that the narrative begins with the image of solid doors, suggesting a line of defense. The home evokes a bygone life, when the unified family was still intact and when Elżbieta could count on the company of her closest companion—the cat.

Let us follow the artist into even more intimate realms. We learn little of her loved ones. Her father continues to treat patients, although the modest “waiting room” and partitioned office seem to be a far cry from the Nadels’ prewar practice. Presumably, the brother works, as was required of all men between the ages of 14–60.35 He also helps around the house. During the so-called “actions,” the men’s work was as guardians, protecting Elżbieta and her mother from deportation. The family’s material struggles and diminishing social status, which for so many begun in the Soviet days, would have worsened in the ghetto environment. The apartment’s cramped space is cluttered with furniture and bookcases crammed full. Rugs cover the floor and pictures decorate the walls, hinting at a bygone life of affluence and tranquility. The family tries to maintain their prewar lifestyle and value system. They resist their social demotion, setting the table with a proper tablecloth and sipping their tea (or some substitute) out of teacups. Despite the war and the Ghetto’s conditions, the family community endures.

This is a secular home: there are no religious objects, and the family’s Polish-Jewish identity is hinted at only cryptically in drawing wieczorem… [in the evening…], with the masthead of the newspaper read before sleep. We see only the first letters “GAZ,” which could indicate Gazeta Żydowska [Jewish Newspaper], printed in Cracow from 1940–42. Then again, it could also indicate Gazeta Lwowska [Lvov Newspaper] – the daily journal for the Galician District). The Nadels’ Polish cultural identity is firmly established. We can infer that Polish was likely Elżbieta’s first (and only) language.36

The question arises: does Obrazki domowe grant us access into daily life in occupied Lvov? To a certain extent, the answer must be yes: the meticulous details might even provide enough information to find the apartment in Lvov today. Using the floorplan and scale, the viewer can orient herself within the home’s tight dimensions and spatial layout. Elżbieta playfully nods to these dynamics in the exercise scene, where her vigorous arm movements send pots and dishes flying and cause the keys to swing from their hook. We quickly comprehend that the Nadels’ living conditions involved certain inconveniences (discomfort, lack of space). The artist winks at this state of things by suggesting that only the cat can find comfortable solace in this house. On the other hand, it is also plain to see that the Nadels enjoyed far nicer living conditions than most households in the Lvov Ghetto.

How did she make do in this environment—a girl in her twenties from a good family, fresh out of art school? Let us meet this young woman. Let us ask her who she is and what she wants to tell us (and how). Let us ask her what stories she will tell from this snare in time and space in which she has been trapped.

To a degree, Elżbieta remains her former self: a girl of vibrant energy with a healthy dose of self-irony. She takes care of herself, maintaining good hygiene and staying in shape. The benefits of these efforts were more than merely physical.37 Like tending to her hair and clothing (with the exception of one dress), these routines help her feel confident, secure, and in control of her reality. She keeps her spirits up (for the most part—the housekeeping scene seems to catch her in a moment of resignation). She takes solace in a warm, lonely evening (o zmroku… [at dusk…]) and draws strength from making art (po pracy… [after work…]). On the other hand, the chamber pot and broom gracing the cover pull us directly into the reality of her daily life: she cleans, does laundry, chops wood. This work is the typical drudgery of domestic life, but it also indicates the sense of responsibility she felt toward her family.38 Familial roles must have shifted,39 for the drawings suggest that Elżbieta shouldered most of the housework duties. Her mother makes only one cameo: she sits at the table, head in her hands, in a posture of resignation.40

Elżbieta’s greatest asset against the invisible but undeniable cruelty of the reality outside her window is her artistic practice. This is a form of resistance and escape: it is how she overcomes her fear. Irony and humor save her in the face of mortal threat.41 (Dark) humor strengthens her morale, becoming a springboard from which she can leap beyond the Ghetto. When we first step into the confined world of Obrazki domowe, we may not recognize this jocular distance as a form of artistic “subterfuge.” Yet this is the source of her resilience in this time of “dark, crushing, smothering fear.”42 I will again cite the diary author who described life in the Warsaw Ghetto: “the saddest, most terrible, and most devastating blow to our health and mental states was the need to live in an atmosphere of constant dread. We were face to face with bare life. It was this relentless vacillation between life and death—the feeling that any moment, the heart could literally break from fear.”43

The humor of Obrazki domowe, drawn out in the titles and commentary, lends the collection an ironic framework that distances the home from the reality outside, conquering fear and keeping despair at bay. Let us take a closer look at the levity recurring in these domestic scenes. Take, for instance, the moments of sleeping and waking in drawings wygodnie… [comfortable…] and rano… [morning…]: privacy cannot exist here, for the cramped quarters have forced the family into close proximity (although this is only made explicit in one vignette: wieczorem [in the evening…]. In this light, could the pervasive humor be a daydream? Could it be a yearning for the past and for just one moment of solitude in the present? A similar sentiment colors the prosaic but stately codzienna przechadzka… [daily stroll…]: on her journey to the bathroom, Elżbieta plays up the contrast between her own dignity and her dingy surroundings.

Elżbieta Nadel, “13. przy stole…” [at the table…], 20.5 × 14 cm, ink/bristol paper, 1942, Muzeum Historii Żydów Polskich POLIN [POLIN Museum of the History of Polish Jews].

Elżbieta Nadel, “14. główne porządki…” [housecleaning…], 20.5 × 14 cm, ink/bristol paper, 1942, Muzeum Historii Żydów Polskich POLIN [POLIN Museum of the History of Polish Jews].

Elżbieta Nadel, “15. wielkie pranie…” [laundry day…], 20.5 × 14 cm, ink/bristol paper, 1942, Muzeum Historii Żydów Polskich POLIN [POLIN Museum of the History of Polish Jews].

Elżbieta Nadel, “16. rznięcie drzewa…” [chopping wood…], 20.5 × 14 cm, ink/bristol paper, 1942, Muzeum Historii Żydów Polskich POLIN [POLIN Museum of the History of Polish Jews].

Elżbieta Nadel, “17. o zmroku…” [at dusk…], 20.5 × 14 cm, ink/bristol paper, 1942, Muzeum Historii Żydów Polskich POLIN [POLIN Museum of the History of Polish Jews].

Elżbieta Nadel, “18. po pracy…” [after work…], ink/bristol paper, 20,5 × 14 cm, 1942, Muzeum Historii Żydów Polskich POLIN [POLIN Museum of the History of Polish Jews].

This is how she wishes to be seen. This is how she sees herself. Obrazki domowe is a rare visual autobiography (self-portrait) of an artist living through a war.44 As we may find in literary memoirs by women from this period, Nadel eludes us, taking cover behind her family and daily duties. Nevertheless, this story comes filtered through her personality and temperament. Like the author of any memoir, her aim is not to reproduce reality, but to express the self, constructing her own identity as a woman, artist and (Polish) Jew who has been brutally wrenched from her former life and community, stripped of her rights, and threatened with death at every turn. Nadel’s sole line of defense against anxiety and despair are her brush, pen and ink, as well as her tragic and ironic sense of humor.

Making art has, for Nadel, the force of the imperative to live. Aside from her art and humor, she also draws strength to endure (and survive) from her steadfast companion—her cat.45 Ever-present, the cat does not draw attention to itself but senses and reacts to all that is happening. Put simply, it is always by Elżbieta’s side. We have no way of knowing if this cat really existed: perhaps it was only the specter of a cat from her past? Bringing animals into the Ghetto was prohibited, although we do know it still happened from time to time. Even so, to care for an animal in such stark conditions would have been insensible (how would you feed it?) if not downright impossible, for because of the widespread hunger, animals were often trapped to be eaten.

Yet regardless of whether the cat existed in reality or only on a metaphorical plane, as a figment of memory, its company gave Elżbieta strength and glued her family together. Taking care of an animal has great benefits for both animal and caretakers.46 Drawn with tenderness and unwavering attention to its behavior, the cat is a protagonist of Elżbieta’s story. This notion is affirmed by Anita Jarzyna’s claim that “nonhuman animal protagonists found in literary works and nonfiction often go unnoticed. They are overlooked on the level of the collective imaginary and belong to the domain of personal images: only then do they come to the fore, and only then does this kind of representation become conceivable.”47

Conclusion

Elżbieta Nadel’s Obrazki domowe. 18 szkiców z natury, drawn in Lvov in July of 1942, tell a woman’s personal story. They are an artifact of individual memory (and already were in the moment of their creation) and an attempt to reconstruct a specific place and time. They also diverge from standard artistic conventions for representing the ghetto experience. While the drawings are emotionally charged, they contain nothing of the nightmare of ghetto life: no hunger, no death, no signs of a daily existence fraught with cruelty and violence. As borders, the window and door seem to be airtight. We know nothing of what goes on outside. There is only the home: a fragile asylum marooned within the reality of occupied Lvov. In this haven, hope is sustained by pale reminders of prewar life: medical consultations, reading, making art.

This subtly rendered self-portrait tells a story of quotidian housework and familial relations. Of paramount importance to the artist and her image of the familial home is the ever-present cat. These drawings are the confession of a girl whose playful yet grounded artistic perception and form carry traces of her femininity, which she hints at coquettishly. In this way, she buries her anxiety and dread within an intimate narrative. After all, equally crucial to this story is that which we do not see—that which the artist chooses to withhold from us (perhaps because she cannot do otherwise).48 Hunger, violence and mass death—the “grand narratives”49 of the Holocaust—do not gain entry into Elżbieta’s world. In their place, Obrazki domowe provides a woman’s private discourse on the Holocaust.

Elżbieta survived, through a combination of chance, the will to live, and outside help. She left behind this keepsake, although we do not know to whom or when. We do not know why she made no effort to recover it after the war. Most likely, the folder of drawings was brought from Lvov to Cracow after the city was liberated, for it was kept in good condition. I want to again underscore the attentiveness, sensitivity, and artistic skill with which these works were executed. So many enigmas and questions are concealed within the drawings, and so much of their artist’s life. This first attempt to analyze Obrazki domowe is motivated in part by my belief in their status as a unique historical and artistic testimony, and in part by a longing to get to know their heroine: a person who constructed her own identity as a woman and artist in spite of the state of constant peril in which she lived.

I am also convinced that artistic narratives of the Holocaust should be incorporated into scholarship, and not only as visual supplements to photography. These documents, no less valuable than wartime diaries, have been overlooked by Holocaust scholars. Art introduces a nuanced language for accounting for the experience of the Holocaust as well as visual renderings of subjectivity (of the artist; of their subjects). As testimonies, visual narratives are in no way secondary to written texts from this historical moment, for they too are records drawn in real time—traces—that capture the moment when the present becomes memory.50

Translated by Eliza Rose

Bibliography

Aleksiun, Natalia. “Food, Money and Barter in the Lvov Ghetto, Eastern Galicia.” In Coping with Hunger and Shortage under German Occucpation in World War II, edited by Tatiana Tönsmeyer, Peter Haslinger, and Agnes Laba, 223-247. London: Palgrave Macmilian, 2018.

Berenstein, Tatiana. “Praca przymusowa ludności żydowskiej w tzw. Dystrykcie Galicja (1941–1944).” Biuletyn Żydowskiego Instytutu Historycznego, no. 1 (1969): 3–45.

Borkowska, Grażyna. “Metafora drożdży, Co to jest literatura/poezja kobieca.” Teksty Drugie, no. 3/4 (1995): 31–46.

Czermińska, Małgorzata. “O autobiografii i autobiograficzności.” In Autobiografia, edited by Małgorzata Czermińska, 5–17. Gdańsk: słowo/obraz terytoria, 2009.

Czerska, Tatiana. Między autobiografią a opowieścią rodzinną. Kobiece narracje osobiste w Polsce po 1944 roku w perspektywie historyczno-kulturowej. Szczecin: Wydawnictwo Naukowe Uniwersytetu Szczecińskiego, 2011.

Friedman, Filip. Zagłada Żydów lwowskich. Lodz: Wydawnictwo Centralnej Żydowskiej Komisji Historycznej, 1945.

Haraway, Donna. The Companion Species Manifesto: Dogs, People, and Significant Otherness. Chicago: Prickly Paradigm Press, 2003.

Honigsman, Jakub. Zagłada Żydów lwowskich (1941–1944). Translated by Adam Redzik. Warsaw: Żydowski Instytut Historyczny, 2007.

Jarzyna, Anita. “Poza imaginarium. O miejscu zwierząt w narracjach o Zagładzie i Zagłady w narracjach o zwierzętach.” Narracje o Zagładzie, no. 3 (2017): 7–18.

Jones, Eliyahu. Żydzi Lwowa w okresie okupacji 1939–1945. Translated by Wiesława Promińska. Lodz: Oficyna Bibliofilów, 1999.

Kraskowska, Ewa. “Humor w kobiecych narracjach o Zagładzie.” In Polskie pisarstwo kobiet w wieku XX: procesy i gatunki, sytuacje i tematy, edited by Ewa Kraskowska and Bogumiła Kaniewska, 421–441. Poznan: Wydawnictwo Naukowe Uniwersytetu im. Adama Mickiewicza, 2015.

Krugłow, Aleksander. “Deportacje ludności żydowskiej z dystryktu Galicja do obozu zagłady w Bełżcu w 1942 r.” Biuletyn Żydowskiego Instytutu Historycznego, no. 151 (1989): 101–118.

Krupiński, Piotr. “Dlaczego gęsi krzyczały?” Zwierzęta i Zagłada w literaturze polskiej XX i XXI wieku. Warsaw: Instytut Badań Literackich, 2016.

Langer, Lawrence L. “The Stage of Memory: Parents and Children in Holocaust Texts and Testimonies.” In Preempting the Holocaust, 131–145. New Haven: Yale University Press, 1998.

Lejeune, Philippe. “The Autobiographical Pact.” In On Autobiography, edited by Paul John Eakin, translated by Katherine Leary. Minneapolis: Minnesota University Press, 1989.

Leociak, Jacek. “Literatura dokumentu osobistego jako źródło do badań nad Zagładą Żydów. Rekonesans metodologiczny.” Zagłada Żydów, no. 1 (2005): 13–31.

Lewin, Abraham. Dziennik, edited by Katarzyna Person, translated by Adam Rutkowski, Magdalena Siek and Gennady Kulikov. Warsaw: Żydowski Instytut Historyczny, 2015.

Mędykowski, Witold. W cieniu gigantów. Pogromy 1941 r. w byłej sowieckiej strefie okupacyjnej. Kontekst historyczny, społeczny i kulturowy. Warsaw: Instytut Studiów Politycznych PAN, 2012.

Nader, Luiza. “Polscy obserwatorzy Zagłady. Studium przypadków z zakresu sztuk wizualnych–uwagi wstępne.” Zagłada Żydów, no. 14 (2018): 165–211.

Narracje o Zagładzie, no. 3: “Zwierzęta/Zagłada” (2017).

Nasiłowska, Anna. “Złe wychowanie jako norma.” Teksty Drugie, no. 6 (2018): 7–10.

Ofer, Dalia, and Lenore J. Weiztman, eds. Women in the Holocaust. New Haven: Yale University Press, 1998.

Petö, Andrea, Louise Hecht, and Karolina Krasuska, eds. Women and the Holocaust. New Perspectives and Challenges. Warsaw: Instytut Badań Literackich, 2015.

Słownik biograficzny lekarzy i farmaceutów ofiar drugiej wojny światowej, vol. 4. 326. Warsaw: Naczelna Izba Lekarska, 2011.

Tec, Nechama. Resilience and Courage. Women, Men, and the Holocaust. New Haven: Yale University Press, 2003.

Ubertowska, Aleksandra. Holokaust. Auto (tanato) grafie. Warsaw: Instytut Badań Literackich PAN, 2014.

Waxman, Zoë. Women in the Holocaust: A Feminist History. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2017.

Documents Analyzed

Registration cards of survivors, Żydowski Instytut Historyczny Archive, no. 19236, 19246.

Dossier for “Moździerz Kazimierz,” Żydowski Instytut Historyczny Archive, sig. Yad Vashem—349/24/1043.

The Central Database of Shoah Victims’ Names (Centralna Baza Ofiar Zagłady), Yad Vashem, no. 436965.

- Lvov [Polish: Lwów], today Lviv, Ukraine. Throughout the article I have chosen to use this spelling in keeping with the text of the artwork and contemporaneous with the historical period under discussion. ↩︎

- On women’s experiences of the Holocaust, see: Dalia Ofer and Lenore J. Weiztman, eds., Women in the Holocaust (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1998); Nechama Tec, Resilience and Courage. Women, Men, and the Holocaust (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2003); Andrea Petö, Louise Hecht and Karolina Krasuska, eds., Women and the Holocaust. New Perspectives and Challenges (Warsaw: Instytut Badań Literackich PAN, 2015); Zoë Waxman, Women in the Holocaust: A Feminist History (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2017). ↩︎

- Jacek Leociak, “Literatura dokumentu osobistego jako źródło do badań nad Zagładą Żydów. Rekonesans metodologiczny” [Personal Documents as Sources for Studying the Holocaust: Methodological Reconnaissance], Zagłada Żydów, no. 1 (2005): 13-31. ↩︎

- Jan Bohdan Gliński, “Nadel Aron,” Słownik biograficzny lekarzy i farmaceutów ofiar drugiej wojny światowej [Biographical Handbook of Doctors and Pharmacists Killed in World War II], vol. 4 (Warsaw: Naczelna Izba Lekarska, 2011), 326. ↩︎

- Urzędowy spis lekarzy uprawnionych do wykonywania praktyki lekarskiej oraz aptek w Rzeczypospolitej Polskiej [Municipal Record of Pharmacies and Doctors Licensed to Practice in the Polish Republic] (Warsaw: R. Olesiński, W. Merkel i S-ka, 1924/1925), 285. Urzędowy spis: lekarzy, lekarzy-dentystów, farmaceutów, felczerów, pielęgniarek, położnych, uprawnionych i samodzielnych techników dentystycznych oraz wykazy: aptek, szpitali, ubezpieczalni społ., ośrodków zdrowia, przychodni samodzielnych, oraz centrali i filii Państwowej Szkoły Higieny [Municipal Record: Doctors, Dentists, Pharmacists, Military Surgeons, Nurses, Midwives, Licensed and Independent Dental Technicians and Formularies of Pharmacies, Hospitals, Social Health Services, Health Centers, Independent Clinics and the Central and Affiliate State Schools of Hygiene] (Warsaw: Ministerstwo Opieki Społecznej, 1939), 281. ↩︎

- The hospital was located in the village Gawartowa Wola, in the Leszno district. Żydowski Instytut Historyczny [Jewish Historical Institute] (ŻIH) Archives, Registration Cards of Survivors, no. 19236, 19246. The ŻIH Archives have preserved the postwar registration cards of Elżbieta and her mother: in 1945, they were registered in Warsaw, and in 1946, in Cracow, under the address Lea Street 5a. ↩︎

- Kwestionariusz świadka Elishevy Landau z 15 czerwca 1987 r. [Questionnaire for Witness Elisheva Landau, June 15, 1987], 1. Dossier for “Moździerz Kazimierz,” ŻIH Archives, sig. Yad Vashem—349/24/1043, 2-3. In 1987, Elisheva Landau and Yala H. Korwin (a painter and poet born as Jala Meisels who lived from 1933–2014) made a formal request to Yad Vashem to honor Kazimierz Moździerz and his sister Helena by instating them in the list of Righteous Among the Nations. The siblings received this distinction in 1989. Elżbieta wrote the following of Kazimierz: “After the Germans invaded Lvov, he was the only one among my friends who did not cut his ties with me. He visited us and was deeply concerned with our welfare.” Kwestionariusz świadka, 1. This short account is expanded upon in a testament from 1955. Regina Nadel listed her wartime addresses as follows: Lvov–Halicki Square 7, Warsaw–Tamka Street 30. The Central Database of Shoah Victims’ Names, no. 436965, Yad Vashem, https://yvng.yadvashem.org/nameDetails.html?language=en&itemId=649945&ind=1 (accessed: 01.26.2020). ↩︎

- The dimensions of the individual cards vary marginally. ↩︎

- This is the only card of a visibly different size. The card itself measures 20.1 x 14.1 cm., and a thin band of paper (5.5 cm. wide) is affixed to its upper-left corner. Unfolded, the card’s total height is 39.7 cm. ↩︎

- The folder’s dimensions: 21.5 x 16.4 (folded); 21 x 40 (unfolded); left wing: (adjoining the title card): 21 x 3; right wing: 21 x 6. Upper insert: 15 x 3 cm.; lower insert: 15 x 6 cm. The dimensions are not quite uniform. For instance, the lower (righthand) wing tapers from 6 cm. at the top to 5.8 cm. at the bottom, by the inscription lipiec [July]. ↩︎

- The square forms a broad, flat frame measuring 2.6 x 2.5 cm. ↩︎

- The letters n, r, w and e consistently appear in a stylized font. ↩︎

- The texts are divided by horizontal lines made with a brush or calligraphy pen on its last drops of ink. ↩︎

- The title card’s dimensions: 20.1 x 14 cm. The border is spaced 1 cm. from the top of the paper and 2 cm. from the bottom. Its side margins are 0.5 cm. The card’s edges appear to be machine-cut with the exception of the left side. ↩︎

- Though they are painted by hand, no trace remains of pencil markings or preliminary outlines. ↩︎

- On August 1 of 1941, the Galician District was incorporated into the “Generalgouvernement.” Two weeks earlier, on July 15, a decree was announced mandating Jews to wear white armbands with the Star of David in blue. Eliyahu Jones, Żydzi Lwowa w okresie okupacji 1939–1945 [Jews in Occupied Lviv: 1939–1945], trans. Wiesława Promińska (Lodz: Oficyna Bibliofilów, 1999), 51. ↩︎

- The bathroom stalls were located outside the apartment but inside the building. The entrance was off the stairwell. The apartment layout suggests that a second entrance to the stalls was located in the courtyard. The hallway was about 13.5 m long and 1.3 m wide. ↩︎

- Luiza Nader, “Polscy obserwatorzy Zagłady. Studium przypadków z zakresu sztuk wizualnych—uwagi wstępne” [Poles Observing the Holocaust: Case Studies in the Visual Arts – Preliminary Comments], Zagłada Żydów, no. 14 (2018): 173. ↩︎

- This pogrom is referred to as the “Prison Action.” See: Filip Friedman, Zagłada Żydów lwowskich [The Genocide of Lviv’s Jews] (Lodz: Wydawnictwo Centralnej Żydowskiej Komisji Historycznej 1945), 6. See, also: Eliyahu Jones, Żydzi Lwowa w okresie okupacji 1939–1945, 47-48; Witold Mędykowski, W cieniu gigantów. Pogromy 1941 r. w byłej sowieckiej strefie okupacyjnej. Kontekst historyczny, społeczny i kulturowy [In the Shadows of Giants: 1941 Pogroms in the Former Soviet-Occupied Zone] (Warsaw: Instytut Studiów Politycznych PAN, 2012), 245-250. ↩︎

- Jones, 50. ↩︎

- Friedman, Zagłada Żydów lwowskich, 6. Most vulnerable were those living in the area bordered by the following streets (I use their pre-war names): Janowska, Gródecka, Zygmuntowska and Legionów, in the vicinity of the streets: Misjonarska, Pod Dębem, Źródlana and Kleparowska, and finally, behind the train embankment on Żółkiewska, Balonowa and Zamarstynowska. In short, violence permeated the entire city. Jones, Żydzi Lwowa w okresie okupacji 1939–1945, 51-54. ↩︎

- Due to the lack of archival data, there is no way to establish the exact number of Jews killed in Lvov during the German Occupation. ↩︎

- Jakub Honigsman, Zagłada Żydów lwowskich (1941-1944) [The Genocide of Lviv’s Jews (1941-1944], trans. Adam Redzik (Warsaw: Żydowski Instytut Historyczny, 2007), 38. ↩︎

- https://yvng.yadvashem.org/nameDetails.html?language=en&itemId=6980273&ind=1 (accessed: 01.26.2020); Gliński, “Nadel Aron,” 326. ↩︎

- Friedman, Zagłada Żydów lwowskich, 13-14, 21. ↩︎

- Natalia Aleksiun, “Food, Money and Barter in the Lvov Ghetto, Eastern Galicia,” in: Coping with Hunger and Shortage under German Occucpation in World War II, eds. Tatiana Tönsmeyer, Peter Haslinger, and Agnes Laba (London: Palgrave Macmilian, 2018), 223-247. ↩︎

- Kwestionariusz świadka, 1. ↩︎

- The murders and raids escalated just before the mass resettlement to the Ghetto. See: Friedman, Zagłada Żydów lwowskich, 11-14. ↩︎

- Abraham Lewin, Dziennik [Diary], trans. Adam Rutkowski, Magdalena Siek and Gennady Kulikov, ed. Katarzyna Person (Warsaw: Żydowski Instytut Historyczny, 2015), 89-90. English translation: Abraham Lewin, A Cup of Tears. A Diary of the Warsaw Ghetto, trans. Christopher Hutton, ed. Antony Polonsky (Glasgow: Fontana Press/Collins, 1990). ↩︎

- Together, these aspects suggest an “autobiographical pact”—a concept introduced by Philippe Lejeune, “The Autobiographical Pact,” in On Autobiography, trans. Katherine Leary, ed. Paul John Eakin (Minnesota: Minnesota University Press, 1989). See also: Małgorzata Czermińska, “O autobiografii i autobiograficzności” [On Autobiography and the Autobiographical], in Autobiografia [Autobiography], ed. Małgorzata Czermińska (Gdańsk: słowo/obraz terytoria, 2009), 5-17. ↩︎

- Roman Zimand, Diarysta Stefan Ż [Stefan Ż, Diarist] (Wrocław: Zakład Narodowy im. Ossolińskich, 1990), 6-45. ↩︎

- Anna Nasiłowska, “Złe wychowanie jako norma” [Bad Upbringing as the Norm], Teksty Drugie, no. 6 (2018): 9. ↩︎

- Tatiana Czerska, Między autobiografią a opowieścią rodzinną. Kobiece narracje osobiste w Polsce po 1944 roku w perspektywie historyczno-kulturowej [Between Autobiography and Family History: Cultural and Historical Perspectives on Women’s Personal Narratives in Poland after 1944] (Szczecin: Wydawnictwo Naukowe Uniwersytetu Szczecińskiego, 2011), 25. ↩︎

- According to Grażyna Borkowska, a work qualifies as “women’s literature/poetry when the subject reveals her gender and actively self-identifies with her sex.” Grażyna Borkowska, “Metafora drożdży. Co to jest literatura/poezja kobieca” [The Metaphor of Yeast: What is Women’s Literature?], Teksty Drugie, no. 3/4 (1995): 38. ↩︎

- Men were subject to compulsory work beginning in 1941. See: Tatiana Berenstein, “Praca przymusowa ludności żydowskiej w tzw. Dystrykcie Galicja (1941-1944)” [Jewish Forced Labor in the “Galicia” District (1941-1944)], Biuletyn Żydowskiego Instytutu Historycznego, no. 1 (1969): 9-12. ↩︎

- See: Kwestionariusz świadka. The artist’s account is written in flawless Polish. ↩︎

- Maintaining good hygiene, which was challenging in the ghetto conditions, is a central theme in women’s narratives of the Holocaust. Aleksandra Ubertowska, Holokaust. Auto (tanato) grafie [Holocaust: Auto (tanato) graphy] (Warsaw: Instytut Badań Literackich PAN, 2014), 176-177. ↩︎

- Nadel’s Obrazki domowe seem emblematic of the words of Aleksandra Ubertowska, who wrote that “privacy and the rudimentary facts of family life became the domain of authors. They designated specific cognitive and narrative perspectives and structured specific ‘frames’ or sequences of the autobiographical story.” Ubertowska, Holokaust, 177. ↩︎

- Lawrence L. Langer, “The Stage of Memory: Parents and Children in Holocaust Texts and Testimonies,” in Preempting the Holocaust (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1998), 131-145. ↩︎

- Kazimierz Moździerz wrote: “The mother of my friend Elżbieta asked me to drive her daughter to Warsaw.” Letter of Kazimierz Moździerz from January 30, 1988, 1, ŻIH, sig. Yad Vashem—349/24/1043, 14. ↩︎

- See, for instance: “The Humor of the Ghetto,” in Barbara Engelking and Jacek Leociak, The Warsaw Ghetto. A Guide to the Perished City (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2009); Ewa Kraskowska, “Humor w kobiecych narracjach o Zagładzie” [Humor in Women’s Narratives of the Holocaust], Polskie pisarstwo kobiet w wieku XX: procesy i gatunki, sytuacje i tematy [Polish Women’s Writing in the 20th Century: Processes and Genres, Situations and Themes], eds. Ewa Kraskowska and Bogumiła Kaniewska (Poznan: Wydawnictwo Naukowe Uniwersytetu im. Adama Mickiewicza, 2015), 430-441. ↩︎

- Lewin, Dziennik, 47. ↩︎

- Lewin, 47. ↩︎

- See: the intermedial memoire of Charlotte Salomon Leben? oder Theater? Ein Singspiel, made in 1941–1942, https://charlotte.jck.nl/ (accessed: 02.06.2020). ↩︎

- Donna Haraway, The Companion Species Manifesto: Dogs, People, and Significant Otherness (Chicago: Prickly Paradigm Press, 2003). ↩︎

- Piotr Krupiński has written about animals in the Holocaust. See: “Dlaczego gęsi krzyczały?” Zwierzęta i Zagłada w literaturze polskiej XX i XXI wieku [“Why Were the Geese Crying?” Animals and the Holocaust in Polish Literature of the 20th and 21st Centuries] (Warsaw: Instytut Badań Literackich PAN, 2016), chapters 9 and 10 in particular; and also Narracje o Zagładzie [Narratives of the Holocaust], no. 3: “Zwierzęta/Zagłada” [Animal/Holocaust] (2017). ↩︎

- Anita Jarzyna, “Poza imaginarium. O miejscu zwierząt w narracjach o Zagładzie i Zagłady w narracjach o zwierzętach” [Beyond the Imaginary: On Animals’ Place in Holocaust Narratives and the Holocaust’s Place in Animal Narratives], Narracje o Zagładzie, no. 3 (2017): 9. ↩︎

- In this article I focus on the biographical aspect of Nadel’s testimony. This multilayered work invites other readings as well. For instance, a psychoanalytical perspective could be generative, following the lines of what Piotr Słodkowski proposes in his analysis of work by Henryk Streng/Marek Włodarski made during the German occupation of Lvov. Słodkowski draws from Melanie Klein and Hanna Segal, according to whom “to create an internal world is also, on the level of the unconscious, to recreate a world that has been lost.” Cited in Piotr Słodkowski, Modernizm żydowsko-polski. Henryk Streng/Marek Włodarski a historia sztuki [Jewish-Polish Modernism. Henryk Streng/Marek Włodarski and the History of Art] (Warsaw: Akademia Sztuk Pięknych, Instytut Badań Literackich PAN, 2019), 383. ↩︎

- Ubertowska, 177. ↩︎

- Pnina Rosenberg, Images and Reflections. Woman in Art of the Holocaust. Works of Art from the Art Collection of the Ghetto Fighters’ House Museum (D.N. Western Galilee: Beit Lohamei Hagetaot/The Ghetto Fighters’ House, 2002). ↩︎

Renata Piątkowska

Dr. Renata Piątkowska is an art historian who works on Jewish art and culture of the nineteenth and twentieth centuries. She is the author of several articles and publications, including the book Between Ziemiańska and Montparnasse: Roman Kramszyk (Warsaw, 2004). At the Museum of the Jewish Historical Institute in Warsaw she has curated the exhibitions: Maurycy Trębacz 1861-1941 (1993); Artur Markowicz 1872-1934: A Retrospective (1995); Roman Kramsztyk (1885-1942) (1997); Friends: Simon Mondzain, Jan Hrynkowski, Władysław Zawadowski (1999), and Our Older Brothers: Painting, Drawings and Graphic Art from the Collections of the Jewish Historical Institute (2001). Since 1999 she has worked at the Museum of the History of Polish Jews POLIN in Warsaw, where she is currently Chief Curator of Collections.